10 Best Adventures of 1909

By:

March 15, 2019

One hundred and ten years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my 100 Best Adventures of the Oughts (1904–1913) list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

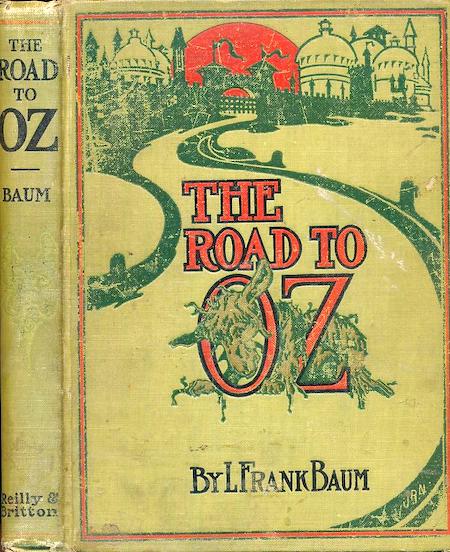

- L. Frank Baum‘s Oz fantasy adventure The Road to Oz. When Dorothy Gale — older and more sophisticated than she was when she first voyaged to Oz — meets a Shaggy Man walking past her family’s farm, she and Toto volunteer to show him the way to the nearest town. The three find themselves in a meta-dimension along with other lost traveler. Button-Bright, a cute little boy who answers most questions with “Don’t know” (and whose head is later changed into a fox’s), will later appear in Baum’s Trot & Cap’n Bill adventure Sky Island. Polychrome, daughter of the Rainbow, is a radiant young girl who must dance to stay warm. Can the adventurers cross the fatal Deadly Desert surrounding Oz and arrive in the Emerald City in time for Ozma’s birthday party? The adventure itself is fairly tame — Baum was phoning it in, at this point — but the payoff is Ozma’s meta-textual bash. The partygoers include not only Baum’s Oz characters but Santa Claus, Ryls and Knooks (from The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus), Queen Zixi of Ix (from Queen Zixi of Ix, or The Story of the Magic Cloak), the Queen of Merryland (from Dot and Tot of Merryland), and John Dough from John Dough and the Cherub, among other non-Oz Baum characters. I enjoy this sort of thing, but not all readers do. Fun facts: This is the fifth Oz book, and the only one to be printed on colored pages — which represent the signature colors of the various countries of Oz that Dorothy and her companions travel through. Baum’s books were literally spectacular — designed to be enjoyed as gorgeous objects.

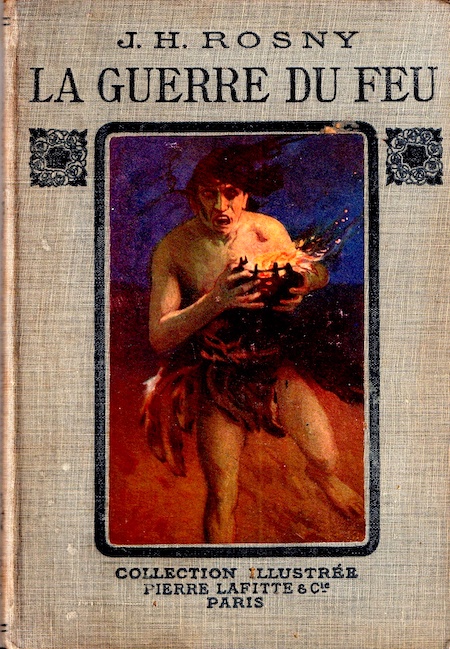

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s children’s atavistic adventure La Guerre du feu (Quest for Fire). At some point during the Ice Age, the people of Ulam — a proto-Franco-Belgian Neanderthal tribe — are attacked by a rival tribe, and their precious fire is stolen. (Although they know how to tend a flame, they can’t generate a new one.) The tribe’s leader promises a woman to whichever young warrior succeeds in bringing back life-giving fire to the tribe. This is a slim novella, but it is action-packed: Naoh, our protagonist, and his two comrades encounter monstrous beasts, alien hominid tribes (some of which appear to be proto-Asian, proto-Scottish, etc.), and must use their wits to overcome all sorts of obstacles. In important ways, Quest for Fire is the ur-text for Goscinny & Uderzo’s Asterix comics: Just as Asterix and Obelix help invent everything from bull fighting in Spain to Swiss cheese in Switzerland, the Ulam questers discover laughter and other crucial early-human technologies. The book’s ending is, I’m sorry to report, a sexist one. Fun facts: “J.-H. Rosny” was the pseudonym of two Belgian brothers who, once they ended their collaboration, added “aîné” (the elder) and “jeune” (the younger) to their monikers. Rosny aîné is considered the most important pioneer in French-language science fiction, after Jules Verne. This book was adapted as a 1981 film starring Ron Perlman, Rae Dawn Chong and Everett McGill; it has a cult following.

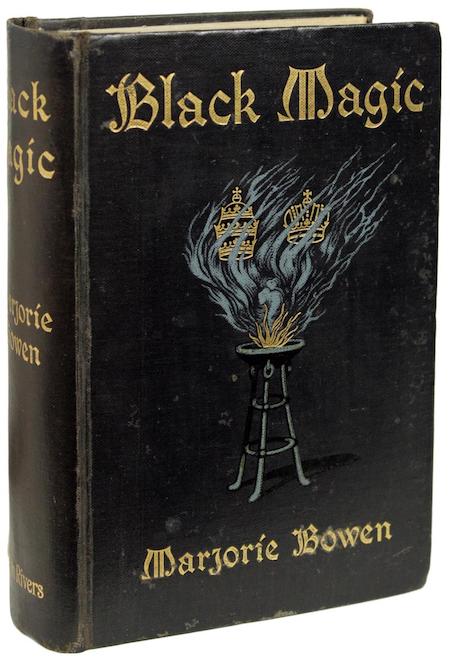

- Marjorie Bowen’s supernatural fantasy adventure Black Magic. In medieval Flanders, Dirk Renswoude, a lonely craftsman of noble birth, meets Thierry, a young scholar who shares Dirk’s fascination with the black arts. Against a background of violent storms, mysterious comets, and a Walpole-esque mood of gothic horror, the two experiment with mystic circles, arcane incantations, and the summoning of demonic visions. Although Thierry is afraid of blasphemy, Dirk is ambitious — and has sworn allegiance to the Devil in return for worldly power. In fact, Dirk aims to become the Antichrist and Satanic Pope! Nevertheless, Dirk is not entirely villainous — he risks everything for Thierry, with whom he has fallen in love… and his backstory reveals a surprise twist that makes us sympathetic to his desire for the agency and independence denied to him by his family. Ysabeau, a cold-blooded schemer and murderess character, also becomes a sympathetic and even heroic figure; and Jacobea, the novel’s tormented heroine, is also well-portrayed. Despite a great deal of awkwardly formal speech, this is a tense, atmospheric thriller that gets entertainingly trippy at times. The novel’s visual set-pieces remind me of Mervyn Peake’s 1946–1959 Gormenghast series. Fun facts: Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long published over 150 historical romances, supernatural horror stories, popular histories and biographies — most frequently under the pseudonym “Marjorie Bowen.” Fritz Leiber, author of the witchcraft thriller Conjure Wife, called Black Magic “brilliant.”

- E.M. Forster’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Machine Stops. Written as a riposte to H.G. Wells’s 1899 technocratic utopia When the Sleeper Wakes, in which Londoners live in a multi-tiered underground society, connected by a vast rail network, Forster’s short novella The Machine Stops takes place in a future civilization in which the outdoors is all but uninhabited. A “Machine” supplies each inhabitant of this global civilization with everything he or she might desire — to a degree where, at this point, few people ever leave their well-appointed apartments. Socialization and entertainment are entirely mediated via the Machine: yes, Forster helped predict the Internet. Who programs the Machine? It’s unclear. In fact, most people are programmed by the Machine. When one courageous individual, Kuno, briefly visits the outside world, he’s shunned by his own mother. Later, when the Machine begins to break down, the inhabitants of this utopian society are utterly helpless. The 2008 Pixar movie WALL·E — in which humanity has grown fat and sessile thanks to automated systems that serve their every need; and in which those systems break down — offers a happy-ending version of the same parable. Fun fact: This novella was first published in The Oxford and Cambridge Review (November 1909). It was written at the height of the author’s powers: between A Room With A View and Howards End. It was published in book form in 1928, as part of the collection The Eternal Moment and Other Stories. Serialized here at HILOBROW.

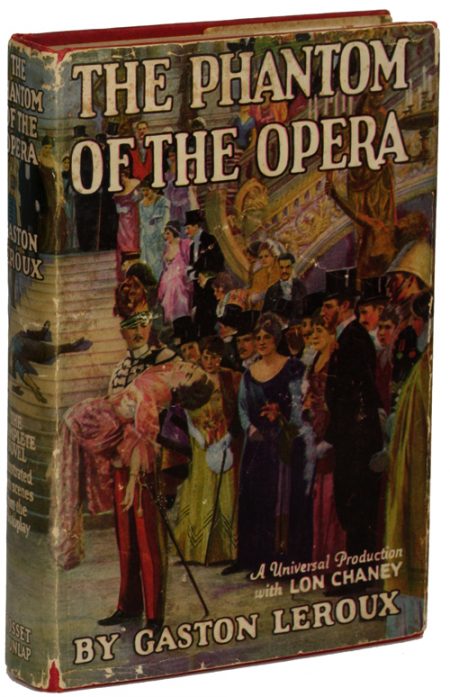

- Gaston Leroux’s horror/romance crime adventure Le Fantôme de l’Opéra (The Phantom of the Opera). Something very strange is happening at the Palais Garnier — an opera house in Paris. A stagehand is found hanged, then the rope around his neck goes missing. The company’s leading soprano, Carlotta, falls ill just before a gala performance… and the young soprano, Christine Daaé, who replaces Carlotta, is strangely accomplished. When the Vicomte Raoul de Chagny, who has loved Christine since childhood, visits her backstage after her triumphant debut, he hears a man’s voice; Christine reveals that she has been secretly tutored by the Angel of Music. Is it true that the Palais Garnier is haunted by an entity — the so-called Phantom of the Opera — who appears as if by magic? If so, the Phantom/Angel now has an agenda: He demands that Christine perform the lead role of Marguerite in the upcoming production of Faust. When his wishes are ignored, Carlotta falls ill again; a chandelier falls and kills an opera-goer. Christine then discovers that the Phantom is a deformed man — a circus performer whose own mother forced him to wear a mask, to cover up his skull-like face — who has fallen in love with her. When Erik abducts Christine, can Raoul penetrate into Erik’s secret lair, a fantastical maze of secret passages deep in the bowels of the opera house, and rescue her before it’s too late? Fun facts: First serialized in Le Gaulois newspaper, 1909–1910. Published in book form, 1911. The Phantom of the Opera has been adapted into various stage and film adaptations, the most notable of which are the 1925 silent film starring Lon Chaney, and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 musical.

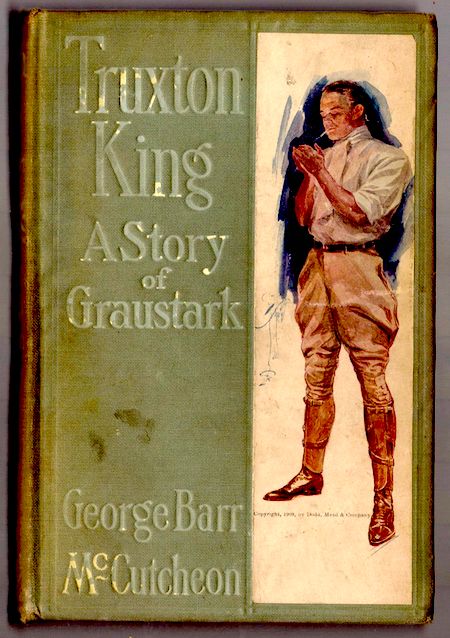

- George Barr McCutcheon’s Graustarkian adventure Truxton King. In the third Graustark novel (a sentimental favorite of mine, because I read it when I was an adolescent, one summer in Maine), Queen Yetive and her dashing American husband, Grenfall Lorry — the protagonists of the first installment in the series, Graustark: The Story of a Love Behind a Throne (1901) — have been killed in an accident! Their seven-year-old son, Prince Robin, a beloved figure, is now ruler of the fictional Eastern European principality. Alas, the Party of Equals — anarchists — are plotting a suicide-bombing assassination of the young prince. Enter another dashing American: “This tall young man in the panama hat and grey flannels was Truxton King, embryo globe-trotter and searcher after the treasures of Romance.” Truxton takes Prince Robin under his wing; is this where Hergé got the Tintin/Abdullah sub-plot of Land of Black Gold and The Red Sea Sharks? Truxton has three love interests, the first of whom is Olga, daughter of a famous Polish anarchist: She hates the Graustarkian nobility because they wouldn’t allow her to marry a prince with whom she’d been in love. Is she involved in the assassination plot? The second is a beautiful young Graustarkian countess, unhappy bride of Marlanx, an exiled Graustarkian royal who has designs on the throne, and who may secretly have something to do with the anarchists! The third is Loraine, sister of the prince’s mentor, John Tullis — an equally dashing, if older American. Can King and Tullis foil the anarchists’ plot — and defend the royal palace against Marlanx’s all-out attack? Fun facts: Adapted by Jerome Storm as a 1923 movie starring John Gilbert, Ruth Clifford, and a young Michael D. Moore — who’d grow up to be assistant/second unit director on dozens of films, from The Ten Commandments and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid to Raiders of the Lost Ark.

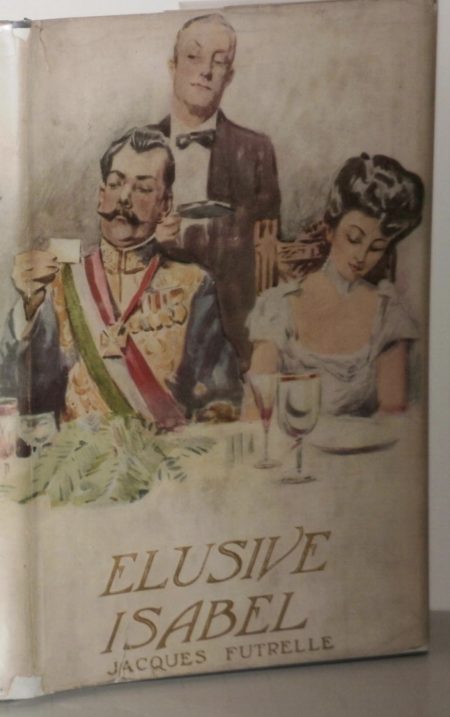

- Jacques Futrelle’s espionage adventure Elusive Isabel (aka The Lady In the Case). “Isabel Thorne” is the alias of a quick-thinking, resourceful, and beautiful young woman of English and Italian ancestry who arrives in Washington, D.C., with the goal of organizing a military alliance of the “Latin” nations — Italy, Spain, France, and South American countries — against America and Great Britain. Isabel is a spy in the employ of the Italian government, and very good at her job… until she falls in love with young Mr. Grimm of the US secret service, who has been charged with preventing the “Latin compact” from being signed. Her brother, meanwhile, is an inventor whose secret weapon makes it possible to fire missiles from submarines (!), a technology that will surely prove lethal to the Anglo-Saxon world order, if only Isabel can succeed in her mission. When Grimm is captured by the conspirators, will Isabel let him die? This is a minor novel, to be sure, but our protagonists are engaging characters — and their battle of wits is an entertaining one. Fun facts: Jacques Futrelle was an American journalist and writer, best known for his detective stories featuring Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen, “The Thinking Machine.” He died in the sinking of the Titanic.

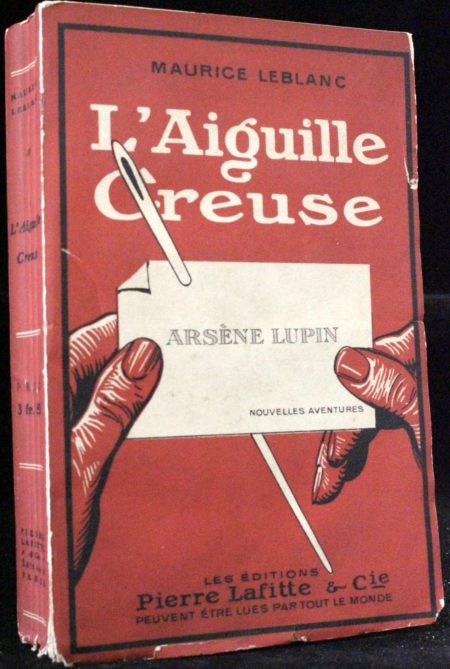

- Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin crime adventure L’Aiguille creuse (The Hollow Needle). The early Arsène Lupin stories are, in a sense, Sherlock Holmes fanfic. Not only was Leblanc writing in response to Arthur Conan Doyle’s wildly popular detective stories (the twist being that his antiheroic protagonist is a Moriarty-like figure), but in the first Lupin collection, 1907’s Arsène Lupin, gentleman cambrioleur, Lupin outwits a supposedly brilliant British detective, “Herlock Sholmès.” Sholmès is also Lupin’s foil in the second Lupin story collection. Here, in the first full-length Lupin novel, Sholmès and Detective-Inspector Guerchard, Lupin’s French nemesis, seek the gentleman burglar in vain, after Lupin steals the Coronet of Princess de Lamballe from M. Gournay-Martin, a millionaire to whom Lupin had previously sent a note threatening to do exactly that. L’Aiguille creuse was originally written as a play, which is why the first half of the book is set in Gournay-Martin’s mansion; it’s a rather dialog-heavy novel, which doesn’t turn thrilling until the halfway point. The surprise hero of this hunted-man story is teenager Isidore Beautrelet, an amateur detective who succeeds in tracking down Lupin. The intrigue is complex, Lupin wears a number of disguises, there’s a fabulous French treasure angle involving L’Homme au Masque de Fer, and a cryptographic clue. Lupin falls in love and fakes his own death, to get out of the crime business. Will Beautrelet, Guerchard, and Sholmès let him get away with it? Fun facts: L’Aiguille creuse was serialized in the magazine Je sais tout from 1908–1909; the first Arsène Lupin story appeared in the same magazine in 1905. A modified version of L’Aiguille creuse was published, in book form, in 1909. Luc Sante suggests that Alexandre Jacob (1879-1954), a French “illegalist” anarchist, was a real-life model for Lupin.

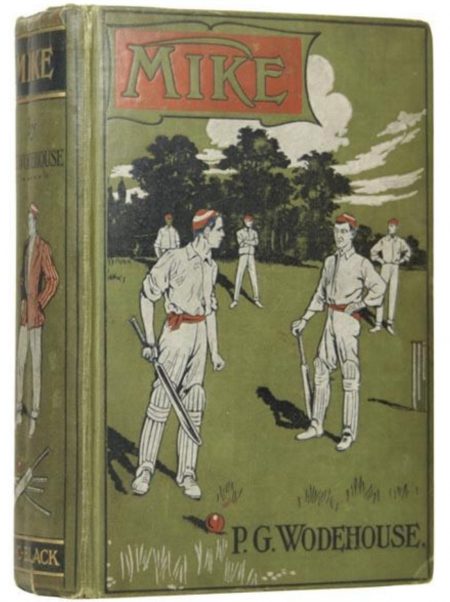

- P.G. Wodehouse’s schoolboy adventure Mike (aka Mike and Psmith). Fifteen-year-old Mike Jackson, our titular protagonist, is a talented cricket player who hopes to win a place on the school’s first team at Wrykyn — a minor public school with a strong cricketing tradition — in his first year there. He befriends Wyatt, who is something of a trouble-maker… and hijinks ensue. Cricket is central to the first section of Mike — a school-sport yarn along the lines of Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857) — so we are treated to thrilling cricket matches, a faked injury, and — yes — a sticky wicket. “One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh would later claim, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame”; Waugh was referring to the second section of Mike, in which an eighteen-year-old Mike is withdrawn from Wrykyn and sent to Sedleigh, a school with a hopeless cricket team… where he meets Psmith. The “P” in Mike’s new chum’s name is silent; he has added it in order to distinguish himself from the common run of Smiths. Psmith is anything but common: He is a fastidious monocle-sporting dandy, and a resourceful trickster who joins with Mike in various anti-authoritarian escapades. The boys eschew cricket, at first, but eventually Mike joins his house’s team and leads them to victory against a rival house… after which they face the first team from Mike’s old school, Wrykyn! Fun facts: The two sections of Mike first appeared, separately, in The Captain, a British magazine for schoolboys to which Wodehouse often contributed. The first part, originally called “Jackson Junior,” was republished in 1953 under the title Mike at Wrykyn, while the second half, “The Lost Lambs,” was released as Enter Psmith in 1935, and later as Mike and Psmith.

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Radium Age science fiction adventure La Guerre des Vampires (The Vampire War). In Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars (1908), adventurer Robert Darvel discovers that Mars’s rather dull-witted humanoids are herded and harvested by the vampiric Erloor. That is to say, it’s a kind of occult, hastily written mashup of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895) and The First Men in the Moon (1901). In fact, Le Rouge has been credited with helping French sci-fi transition from its Vernean incorporation of science to a Wellsian imaginative fictionalization of science. In the feuilleton installments that make up this sequel, Darvel’s comrades back on Earth — including several brilliant inventors, the lovely millionairess Miss Teramond, and an avant-garde chef (!) — work feverishly in their Tunisian laboratory to communicate with Darvel. Their blind servant, Zarouk, can perceive “obscure radiations of the electromagnetic spectrum,” which will come in handy when invisible creatures follow Darvel back to Earth, kidnap Miss Teramond, and threaten to prey on all humankind. We discover that the Erloor are controlled by invisible, blood-drinking octopus-bat creatures, which inhabit a kind of massive Habitrail. Moreover, these Vampires are themselves preyed upon by a mysterious, psychic, volcano-dwelling entity. What can it be? Fun facts: Le Rouge’s Mars sequence was translated and published in omnibus form by Brian Stableford, in 2008; and also by David Beus and Brian Evenson, in 2015.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.