PLANET OF PERIL (37)

By:

March 12, 2019

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

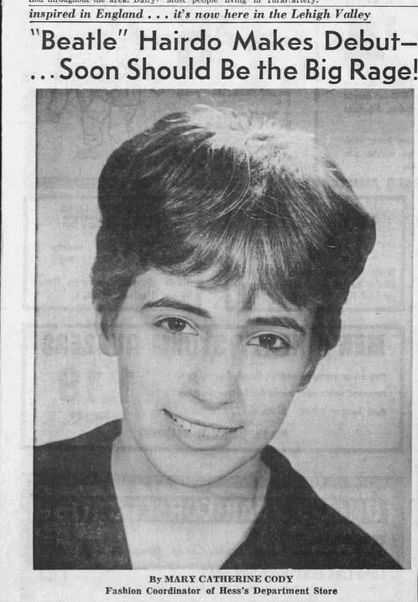

On January 15, 1964, Hess’s Department Store in Allentown, Pennsylvania, got out ahead of what promised to be the next “Big Rage.” An ad in The Morning Call newspaper showed a cute doe-eyed girl with a short mop-top haircut. “The British ‘Beatles,’ a sensational singing quartet in England whose records are now becoming top hits in the U.S., have inspired a new hair-do,” explained the copy. A “Beatle cut” was “easy to care for,” especially when compared to the elaborately set bouffant styles then popular for women, and “could be yours… for only $3” at the store’s Jon Michele Beauty Salon.

The “Barnum of the Boondocks,” Hess’s was known for its stunt marketing. Designer Rudi Gernreich’s topless “monokini” bathing suit was created as a one-off for a photoshoot of futurist fashions, but then Hess’s put it in an order. Protestors picketed the store when the suits arrived in the summer of 1964. Depending on which source you consult, the store sold two dozen (“there are a lot of private pools around here,” the store’s sales promotion manager told The New York Times in 1966), twelve, or zero.

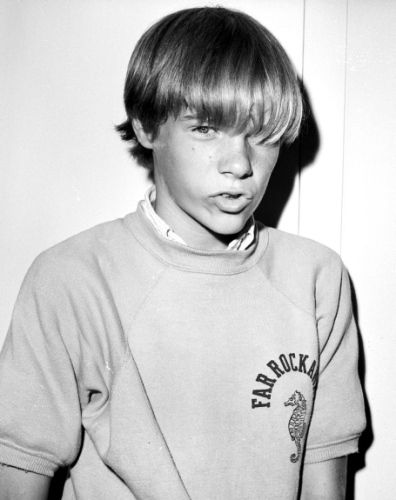

Hess’s correctly predicted the fad, but incorrectly identified the gender of the teens who would be getting Beatle haircuts — or more precisely, who would stop getting haircuts altogether. With their two appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, the Beatles spawned countless garage bands and a moral panic, what one contemporary observer called “The Great Haircut Crisis.”

Middle-class white boys who were not usually policed for their appearance like their sisters (bobbed hair, rouge, miniskirts, to name but a few pearl-clutchers) or for their very existence, like black teenage boys, were suddenly on the front lines in a skirmish between conformism (supported by school administrators, teachers, coaches, and parents) and individualism (long-haired boys and their defenders).

When Elvis Presley first appeared on Sullivan’s show in 1956, he wore a modified version of a haircut already associated with juvenile delinquency: the ducktail (also known as a “D.A.” or “duck’s ass” for the way it looked from the back). But while Elvis rocketed to stardom, the ducktail never infiltrated schools to the extent long hair did a decade later — principals made a stand against it, schools instituted dress codes, and kids complied.

Perhaps one reason the style failed to take off was that a ducktail required frequent combing and a commitment to butch wax or similar “greasy kid stuff” pomade. Long hair required no such upkeep. The Beatles themselves sported ducktails until a chance encounter with a group of mop-topped existentialist artists during the group’s engagement at a club in Hamburg, Germany, led to their new look. Photographer Astrid Kirchherr, credited with wielding the scissors, said she did not invent the haircut, but merely copied what other bohemians were already wearing.

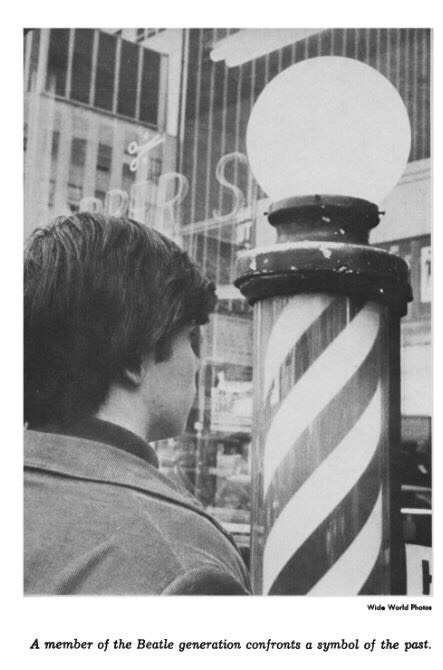

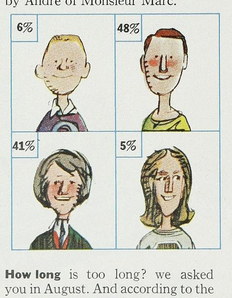

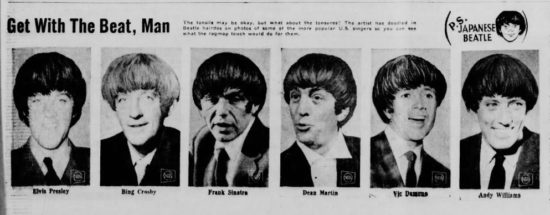

Long hair almost immediately became a line of demarcation between adults and teenagers. At first, adults mocked the Fab Four’s hair (witness any number of comedy skits or photos featuring celebrities or town fathers in Beatle wigs), while their sons combed their hair forward as best they could while they waited for it to grow out. “Up until about two years ago, all the hippest young men — the class officers, the athletes, the all-A students — wore their hair fairly short,” explained Ladies Home Journal in August 1965, though its example of “the hippest” makes one wonder how often its editors got out of the house. “Came the folk singers, the Beatles and the English revolution, and suddenly many young men have a whole new look…. In fact, the way a boy wears his hair is a barometer of the way he feels about life in general.” How the Journal felt about male hairstyles was apparent from the subjective descriptions given in a quiz asking readers to choose their favorite of four lengths: “ultraconservative” crew cut, medium-length on a “lady’s man,” “artsy” long hair (that came just below the ears), and “a shoulder-length bob,” signifying “a member of a far-out singing group or an exhibitionist.”

Indeed, more than one boy faced with suspension or expulsion from high school explained that he needed to wear his hair long in order to make money playing with his rock-and-roll band. Three members of Sound Unlimited were suspended from their high school in Dallas, pending haircuts, but reinstated when their agent threatened to sue. The only National Merit Scholar at Unionville High School in Pennsylvania decided to finish out his “education by television” when he was suspended for refusing to cut his hair because he played in a band.

The tensions between long-haired hipsters and the rest of the world provided rich material for teen bands and others: “Get your scissors outta my hair…” sang The Kavaliers, an Alabama garage band in 1966, “…can’t you see that I wanna be free?” to give but one example.

School administrators frequently argued that long hair on boys was “disruptive” and “unhygienic” (boys allegedly didn’t wash their hair as frequently as girls). A female science teacher in Texas testified that girls could “safely handle their hair, but not boys” when it came to working around the open flame of a Bunsen burner. As more and more male students adopted long hair, schools fought back with updated dress codes. For example, a 1966 dress code from a junior high school in Texas mandated that “Boys will not be allowed to attend school with dyed hair, odd-ball haircuts, duck-tails, over-laps, or overly great amounts of hair.” But what constituted an “odd-ball” haircut or “overly great amounts of hair”? Four years later, a Michigan high school dress code was very specific: “the hair must be [no longer than] eyebrow length in front, collar length without curls in the back, with no more than half an ear covered on each side.”

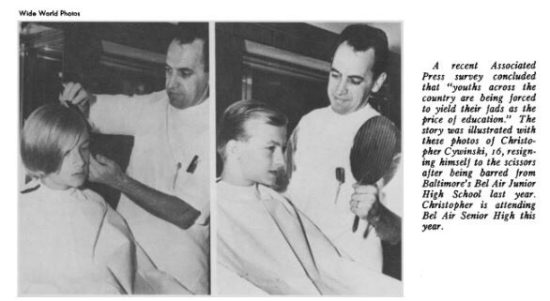

When it came to disruption, however, the people who appeared to get the most bent out of shape by the presence of long-haired boys were adults. The principal of a Connecticut high school made a class-by-class inspection one day in 1968, then suspended 51 students whose hair he found too long. The school administrator at a Catholic high school in New Hampshire pulled 18 students out of their classes, loaded them onto a bus, and took them to a barber where they were given haircuts that they didn’t want, and were made to pay for. The boys, aged 16 to 18, had been told “for months” to get haircuts, and thought the priest was kidding when he said he’d take them to the barber if they ignored a final warning.

Underlying much of the anti-long-hair rhetoric was plain old homophobia. One of the Ohio high school girls who responded to a roving reporter’s question in 1966 (“Are Beatle Haircuts Okay?”), said she found long hair “effeminate-looking,” while another said wearers “didn’t seem to be as masculine” as other boys. That same year, Pat Morrison, a freshman sprinter on Stanford’s track team (papers noted that he was from that new bastion of hip, London) “refused to shed his Beatle-do” at the request of his coach, and was kicked off the team despite his record-setting pace in an early meet. Reporters covering the contretemps made no effort to hide what they really thought the problem was. “When carefully marcelled, he is the first track athlete to look like Martha Washington. There is also a striking resemblance to [1950s professional wrestling sensation] Gorgeous George,” wrote Los Angeles Times sports columnist Sid Ziff. He asked a “ranking tennis gal” from Southern California what she thought about Morrison’s hair. It was “unnatural” she told Ziff, and made the sprinter “look very much like a girl.” She could never “go for a type like that” because “long curls” detracted “from their manliness.”

The power struggle over hair also played out in homes across the nation. One tearful mother wrote to Dear Abby in 1968: “My husband told our 17-year-old son that if he didn’t come home with a haircut tonight, he didn’t have to come home at all. It is midnight, and Jon is not home yet.” Abby replied that while she preferred short hair, long hair was “in.” The boy’s father needed to practice “patience and understanding,” and concentrate on the lasting aspects of his son’s personality. His hair would “grow shorter (or disappear entirely) soon enough,” Abby dryly noted.

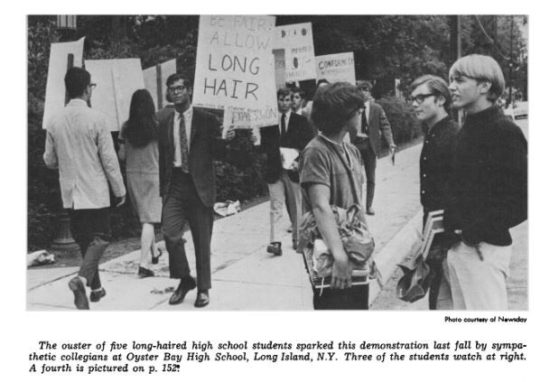

Many parents considered a son’s willingness to stand up to school authorities on the hair issue to be one of those “lasting aspects” of his character, even if they, like Abby preferred short hair. Many helped their sons pursue legal remedies to what they viewed as arbitrary rules about hair length. In her study of “legal challenges to high school rules about the length of male students’ hair,” circa 1965–1975, historian Gael Graham found over 100 “hair cases” appealed to federal circuit courts, nine all the way to the Supreme Court. Graham paraphrased the testimony of a father of one such plaintiff, who, in the early 1970s, “told the court that, although he did not want his son to break rules for the sport of it, he did want him to stand up for his individual rights.”

The handwriting was on the wall long before then, of course. Instead of a teenage fad that faded, long hair was adopted (some might say co-opted) by adults. “Barber Predicts Success of Hairstyling for Fellows” was a headline in the Greenville, South Carolina, newspaper in July 1968. Already, hairstyling was “most popular among business executives, salesmen and professional men; but eventually it will probably become as popular as a weekly haircut,” the paper predicted.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.