AFROFUTURISM (4)

By:

March 8, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

Well, all right, Star Child!

Citizens of the universe, recording angels,

We have returned to claim the pyramids.

Partying on the mothership,

I am the mothership connection!— from “Mothership Connection (Star Child),” the 1975 Parliament song which first introduced George Clinton’s messianic-alien alter ego Star Child

Gimme the paw, gimme the ball, take the top shift (ball)

Call my girls and put ’em all on a spaceship (brr)— from “APESHIT,” a 2018 song by Beyoncé and Jay-Z

Afrocentric spaceships are a trip; Afrofuturists put so much inventiveness into the design of transportation! Known by various names — motherships, UFOs, space hoopties — these vessels of transportation, in music and movies, bring me joy.

As I’ve written before, George Clinton’s 1975 sci-fi album Mothership Connection first introduced me to the concept of Afrocentric space travel. I learned about the P-Funk Afronaut mythology by studying Pedro Bell and Overton Lloyd’s illustrations, which decorate albums and liner notes for recordings of music performed by Clinton and Bootsy Collin’s collective of musicians under the names Parliament and Funkadelic.

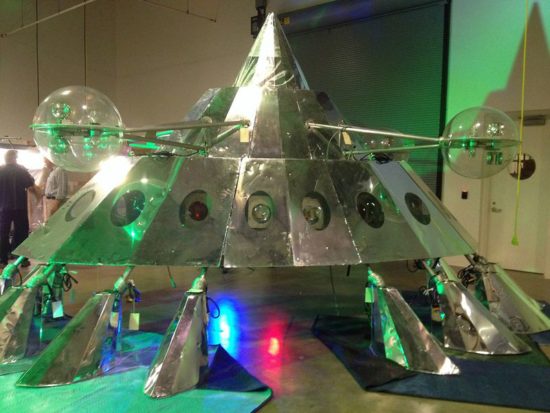

I loved the pyramid-shaped Mothership and, as an adolescent, I would stare at it for hours while listening to the album’s title track over and over again. Parliament’s Mothership is so iconic that in 2014, George Clinton donated a copy of the stage prop to the Smithsonian. Since then, I’ve gained a broader awareness of all types of music and discovered that Clinton wasn’t the only Afrofuturist entranced with space travel.

Influenced by John Coltrane‘s posthumous jazz album Intersteller Space (recorded 1967, released 1974), jazz musicians like Ornette Coleman, and Charles Earland, not to mention Chick Corea’s jazz fusion group Return to Forever (1972–1977), experimented with ways to communicate the sound of space.

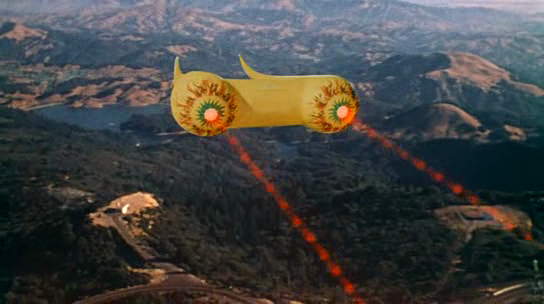

In 1971, the experimentalist jazz composer and bandleader Sun Ra gave lectures at UC Berkeley about the interdimensional aspects of his compositions — and eventually made a film about an alien who uses music to teleport people to distant planets. Called Space is the Place, the 1974 film intercuts shots of Sun Ra performing with his Arkestra with vignettes of Sun Ra exploring distant planets aboard a yellow spaceship that looks like two breasts. The Beatles may have had a yellow submarine, but Sun Ra preferred space mammaries.

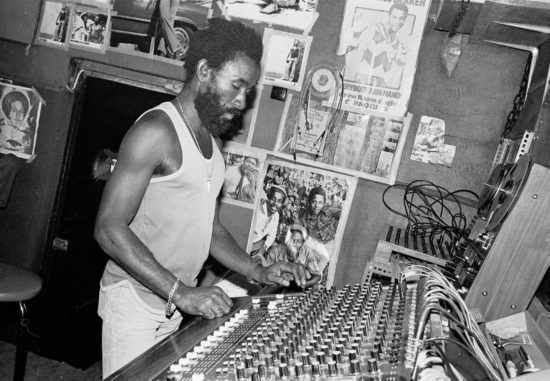

At Black Ark Studios in Jamaica, meanwhile, reggae producer Lee “Scratch” Perry used overdubbing techniques to give a futuristic flair to songs like I-Roy’s 1973 hit “Space Flight.”

One thing that I love about the 1970s-era sci-fi music of these Afrofuturist musicians is its optimism. Clinton, Sun Ra, I-Roy and others — check out “UFOs,” on the Motown group The Undisputed Truth’s 1975 album Cosmic Truth — hailed extraterrestrials as potential liberators, arriving to scoop black people up in their UFOs and whisk them away to paradise.

It’s no coincidence that both Sun Ra and Lee “Scratch” Perry used the term ark in their work. Perry’s studio was an ark of sorts, and Sun Ra’s Arkestra played music with teleportation properties; both artists explored the physics of sound in order to transport us.

The idea of a space ark strongly resonated, in the 1970s, for African Americans — and for many of us, still today. The chorus of Parliament’s “Mothership Connection (Star Child)” quotes the sassy gospel song “Swing Down Sweet Chariot,” which is itself a riff on “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” a hymn written in the 1860s by Wallis Willis, a Choctaw freedman.

Whether or not they specifically reference Negro spirituals and gospel standards, the songs mentioned here and others like them echo the desire for flight found in, say, Albert E. Brumley’s 1932 song “I’ll Fly Away.”

When the shadows of this life have gone,

I’ll fly away.

Like a bird from prison bars has flown,

I’ll fly away.

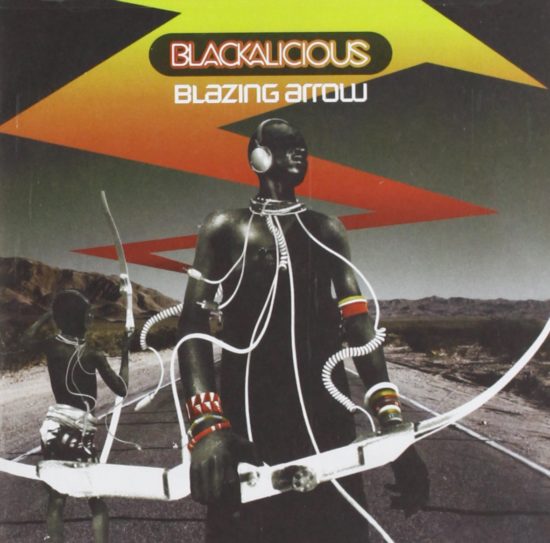

Gil Scott-Heron represents the spirit of the ’70s, for example, when he makes a guest appearance on Blackalicious’s great 2002 song “First in Flight” (from the album Blazing Arrow): “Cause all we got is rhythm and timin’/We go beyond the edge of the sky.” The limitlessness of flight has always suggested, to African Americans, liberation not only from actual oppression but from repression: worries, misery.

Today, although the psychedelic, Space Age vibe has largely evaporated from black culture, the idea of the gleeful Afronaut still pops up in Afrofuturistic productions.

I loved the organic design of the Red Lectroid ships in 1984’s The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (shown above), for example. Missy Elliot plays a rapping astronaut in her 1997 “Sock it to Me,” video and sings to glowing UFOs in her 2003 “Pass That Dutch” video. And I enjoyed watching Janelle Monae pilot her spaceship in the the “Autofac” episode of the 2018 TV anthology series Philip K Dick’s Electric Dreams on Amazon Prime.

But times have changed. The aliens who offer to trade massive rewards in exchange for America’s black population don’t seem altruistic in Derrick Bell’s 1992 short story “The Space Traders.” Bell, the first tenured African-American professor of law at Harvard Law School, is one of the originators of critical race theory; he wrote this story as a thought experiment.

Reginald and Warrington Hudlin adapted Bell’s story for an episode in HBO’s multi-ethnic horror series, Cosmic Slop — the series title is an homage to a 1973 Funkadelic album, and George Clinton himself hosted. Sharp-eyed viewers enjoyed the irony of seeing Robert Guillaume, who played the titular head of household affairs for a state governor in the show Benson, take on the role of a Republican professor forced to mediate between the African-American community and a government eager to make the trade. Having watched civil rights gains erode in the face of Reagan- and Bush-era conservatism, African Americans in Bell’s story story are highly skeptical of the government’s goodwill.

Michael and Janet Jackson’s 1995 video for “Scream” — an angry rebuttal to the tabloid coverage of the child sexual abuse accusations made against Jackson in 1993 — continues to fascinate me. The artists perform under the surveillance of the cameras aboard a sleek spaceship. We can’t tell if they are bored space travelers or test subjects. As the violence in the video intensifies, it’s hard to ignore the song’s lyrics about social injustice and inequity.

In 1995, people were shocked by the rage that Michael Jackson’s dancing displayed. It’s still a shock to revisit the song’s lyrics in the wake of the 2019 HBO documentary Leaving Neverland.

With such delusions, don’t it make you wanna scream?

You’re bash abusin’ victimize within the scheme

You try to cope with every lie they scrutinize

Somebody please have mercy ’cause I just can’t take it!

My interpretation of this video, today: Michael Jackson was abducted by aliens, examined, and found wanting. Now they’re sending him back to Earth — which is to say, Hell — where he belongs.

Jason Heller’s 2018 book Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded was a crucial resource for this essay.

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.