AFROFUTURISM (3)

By:

February 25, 2019

We are pleased to present a 10-part series exploring the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of Afrofuturism, by HILOBROW friend Adrienne Crew — who previously brought us an exploration of P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.

I love historical romances. I’m a regular on the vintage dance circuit. And I conduct walking tours of Southern California residences inhabited by Jazz Age legends like Dorothy Parker, S.J. Perelman, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. I’m also a black geek girl who adores science fiction… so you might assume that I’d be particularly fond of time-travel narratives. In fact, I hate most of them! I’m forever searching for exactly the right kind of time-travel novel or movie… but they’re nearly impossible to find.

For an American of African descent, the notion of traveling to the past is a painful one. In no matter which time period a person like me might arrive, if I’m in Europe or a European colony, I might very likely be raped, enslaved, lynched, or all of the above. I’ve asked African American friends about which past time period they’d most like to visit, and they always agree with me that the present is the best. Brandi Brown, a young African American stand-up comedian who formerly worked in advertising, once joked that when she was asked, “Don’t you wish you could go back and work in the time of Mad Men?, her response was: “I would not like that at all! I’m a huge fan of my current rights.” The very idea of time travel, for African Americans, heightens our anxiety about the history of anti-black white supremacy in the world.

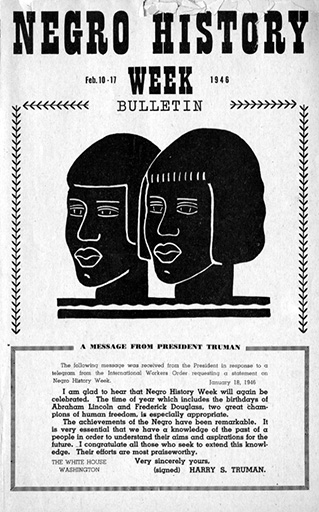

Here it is, Black History Month, and I’m saying that I don’t enjoy thinking about Black History, much less imagining actually going there. I’m not alone: Although Carter G. Woodson, a child of former slaves who in 1926 launched the celebration of “Negro History Week” (the precursor of Black History Month), thought it important for blacks to know the unvarnished truth of their heritage, in recent years many cultural programmers have rebranded Black History Month as Black Heritage Month — celebrating the rich culture and positive contributions of African Americans, that is, instead of solely focusing on the injustices inflicted on our forebears. This is not to say that black people shouldn’t revisit our painful past; I’m just explaining that we rarely enjoy doing so.

For someone like me, who appreciates science fiction and fantasy as escapist literature, it’s difficult to escape into a fantasy of visiting the past. Entertainments like Back to the Future, Tim Powers’s Anubis Gates, Kate & Leopold, Britcom Lost in Austen, Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book and sequels, Project Almanac, Neal Stephenson and Nicole Galland’s The Rise and Fall of D.O.D.O., no matter how self-aware or complex they may be, force me to make a choice I don’t want to make. Either I pretend that the past in which my ancestors were enslaved didn’t happen, thus erasing myself, or else a bitter voice in my head interrupts my pleasurable experience with complaints about how privileged and culturally insensitive their creators must be.

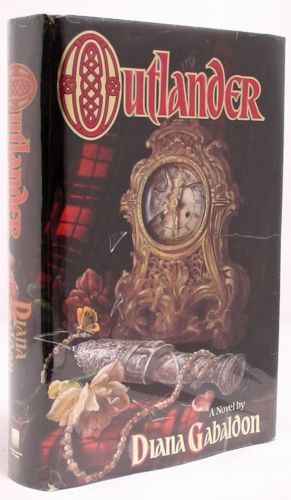

I’d particularly love to enjoy Diana Gabaldon’s trashy historical-romance/sci-fi Outlander series (1991–ongoing). I appreciate many aspects of these books! But the battle in my head makes it impossible for me to enjoy them fully. Here’s why:

Outlander, the first installment in Gabaldon’s series, follows the adventures of Claire Beauchamp Randall, a WWII-era nurse transported to 18th-century Scotland. As Claire plots a return to her husband in the modern age, she develops an irresistible attraction to a charismatic Scot, Jamie Fraser, and embarks on a journey to change Scottish history — by preventing the final Jacobite rising of 1745. It’s a sexy and compelling read. Claire is smart, opinionated, and brash. Jamie is not only a muscular ginger with keen emotional intelligence, but a proto-feminist who loves Claire for her brains and supports her dreams. Their love story is right up this reader’s alley.

In subsequent books, the pair journeys beyond Scotland. When she lands in Jamaica, Claire refuses ownership of a slave, because she has a black best friend in (20th-century) Boston. Eventually, Claire and Jamie make their home in colonial North Carolina. During a visit to a plantation owned by Jamie’s relatives, Claire recoils in horror at the slaves’ plight. In the end, Claire and Jamie decamp to the undeveloped back country of North Carolina to settle territory obtained via a treaty negotiated with the indigenous peoples of the area: moral problem resolved, or elided anyway. But instead of distancing herself from the institution of slavery, why doesn’t Claire become an early abolitionist? After all, Louis X abolished slavery within France as early as 1315. These are the kind of questions that push me out of Gabaldon’s otherwise compelling fiction.

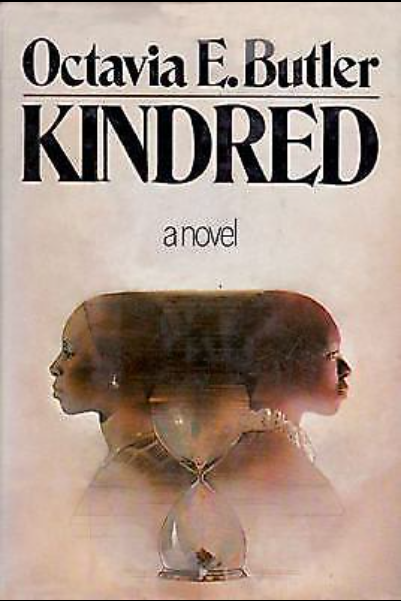

By contrast, Kindred, Octavia E. Butler’s 1979 time-travel tale, doesn’t flinch from confronting the legal institution of human chattel enslavement in 18th- and 19th-century America; in fact, Butler folds her brand of speculative futurism into the slave narrative genre.

Dana, a black woman living in Los Angeles in 1976, inexplicably finds herself saving a boy from drowning in a river — on a Maryland plantation, in 1815. Gradually, she begins popping in and out of the 19th century at random. Sometimes the visitation is just a few minutes, while other sequences last for weeks. Dana’s white husband, Kevin, is powerless to help; later, he joins Dana on her travel through time and witnesses the horrors of chattel slavery for himself. At one point, he must masquerade as his wife’s owner. Unlike Diana Gabaldon’s Claire, Kevin does more than merely express horror at the cruel system of slavery. He becomes an abolitionist, and uses his privilege as a white man to organize escape routes for runaway slaves. Kindred is an extraordinary novel, but that doesn’t mean I enjoy reading it. I revisit it once every ten years or so.

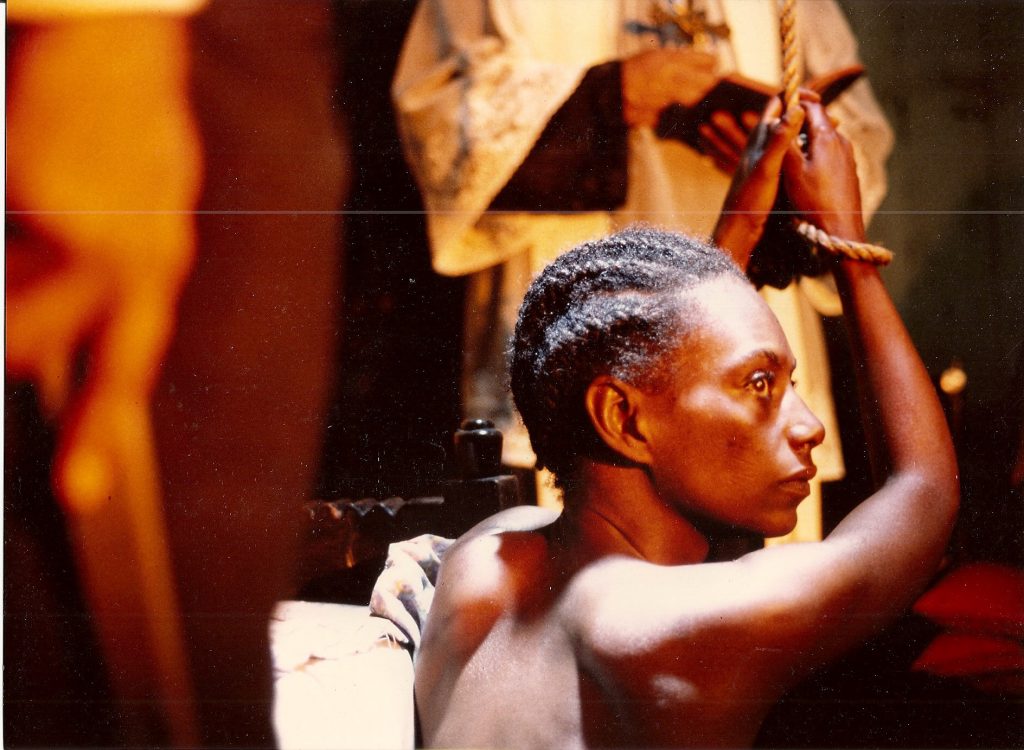

Same thing goes for Sankofa, the 1993 Burkinabé film directed by Haile Gerima, which won international acclaim for its depiction of African resistance to slavery. Much as in Kindred, a 20th-century woman — Mona (Oyafunmike Ogunlano), a self-involved African-American model on a film shoot in Ghana — finds herself transported into the body of a 19th-century female slave working on a Southern plantation. Mona is raped by her owner and subjected to many acts of brutality; she eventually joins in a slave rebellion and kills her tormentor. The word sankofa means something like “go back, and gain wisdom, power, and hope,” but I’m personally not enthusiastic about the idea of witnessing the institution of slavery in antebellum America for myself.

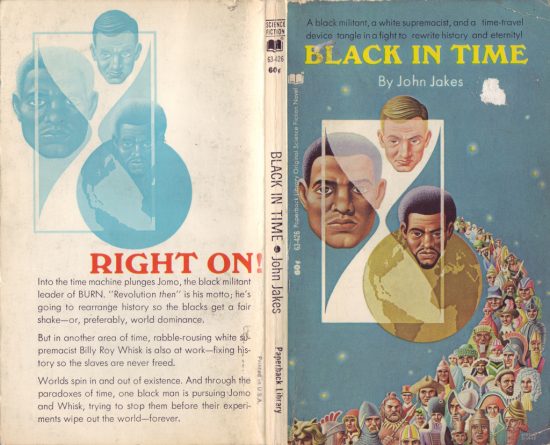

John Jakes’s 1970 potboiler Black in Time sounds bad, but interesting: A black militant travels back in time to reverse the effects of white supremacy, while a white supremacist uses the same tech to ensure the continuation of slavery in the United States. Steve Harper made a six-episode webseries called Send Me, about contemporary African Americans who volunteer to go back in time to experience slavery. And who didn’t enjoy the scene in Men in Black 3 (2012) where Will Smith — having traveled back to 1969, on a mission to save Agent K — “neuralyzes” two racist cops and lectures them, “Just because you see a black man drivin’ in a nice car, does not mean it’s stolen!”

However, I’m just not interested in any of these fantasies. As for the idea that it’s somehow uplifting for today’s African Americans to re-live the experience of chattel slavery, I can assure you that — as we navigate institutional structures based on white supremacy — there’s no need to travel back in time, for that sort of thing.

This Afrofuturist would like to read or watch time-travel narratives that neither require me to ignore African Americans’ painful history, nor trigger my social-consciousness matrix. A title card in Terence Nance’s excellent HBO variety show Random Acts of Flyness mighty sum the situation up like so: “#438 of 1,000 Things A Black Person Shouldn’t Have to Worry About.”

I’m not the only one who struggles with the absurdities of engaging in problematic texts and internalized racism. In Aydrea Walden’s web series Black Girl in a Big Dress, Walden plays an African American Anglophile cosplayer who navigates the Victorian re-enactment scene while observing the micro-aggressions and racist notions of her friends and coworkers.

I was looking forward to the Netflix time travel-themed TV shows Travelers and Siempre Bruja, both of which feature black women in their cast, but both let me down.

In Travelers, a squad from the future download their consciousnesses into random people in a city in 2018 — in order to avert a global disaster that will have dire consequences for future generations. One traveler downloads into the body of an African American woman dealing with an abusive ex. Although the show takes the time to explore another traveler’s dilemma when she discovers that she’s downloaded into the body of mentally disabled woman whose incapacity interferes with the traveler’s mission, it never reveals specific instances of what the traveler downloaded into the African American woman experiences as a female person of color in contemporary society.

Siempre Bruja received some advance acclaim for “showing that black witches can be human, powerful, and the stars of their own stories,” so I was excited to see it. It sounds just as ridiculous and over-the-top as Outlander, in a good way — but it’s about Carmen, an Afro-Colombian witch who time travels forward from the 17th century to 21st-century Cartagena. What’s not to like? Plenty. The series never addresses Carmen’s feelings about being enslaved and then freed into a world that has eliminated slavery and race-based caste systems. In the modern age, she continues to subjugate herself. Critics of color were also enraged that the show continues the trope where a slave of color is irrationally devoted to a white lover who promises to marry and free her… yet leaves the institution of slavery intact. You would think that Carmen’s new allies would raise her consciousness just a bit.

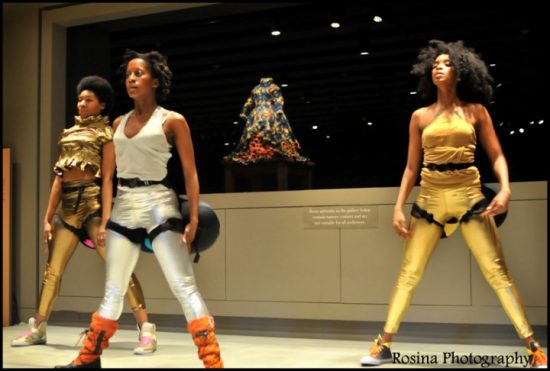

Happily, newer Afrofuturism practitioners have also helped me with my conflicting feelings. Last fall in Washington, D.C., dancer and performance artist Holly Bass presented a theatrical piece called The Trans-Atlantic Time Traveling Company. The show is about black time-travelers from the future who travel to the 19th-century South as a minstrel troupe of freed women — who hide their Afrofuturistic rocket boosters under the bustles.

Now, that’s some big-booty entertainment I can get behind.

AFROFUTURISM: INTRODUCTION | HAIR POLITICS | BODY HORROR | TIME TRAVEL | SWEET CHARIOTS | ALIEN NATION | A WAY OUT OF NO WAY | ROBOT LIBERATION | ADAPTATION & HYBRIDISM | STARSEEDS | BLACK UTOPIA. ALSO SEE: P-FUNK AFROFUTURISM | SAMUEL R. DELANY | OCTAVIA E. BUTLER | W.E.B. DUBOIS’S “THE COMET”.