Best YA & YYA Lit 1969

By:

January 28, 2019

SEE: 100 BEST YA & YYA ADVENTURES OF THE SIXTIES (1964–1973)

Fifty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite YA and YYA adventures published in 1969. Enjoy!

- Peter Dickinson’s YA fantasy adventure Heartsease. When a mysterious enchantment settles over England, many of its white, working-class inhabitants rapidly revert to an ignorant, xenophobic way of looking at the world; and, once nearly all of those who are unaffected — in particular, all immigrants — have fled England for the continent, the country makes (to coin a phrase) a hard Brexit… from the 20th century. What’s more, anyone who displays any knowledge of how modern technology or machinery functions is persecuted as a witch. One such “witch,” who is rescued by three children in a Cotswold village, turns out to be an American intelligence agent who has bravely parachuted in to investigate England’s mysterious “Changes.” Horse-loving Margaret somewhat reluctantly helps her cousin, Jonathan, and the family’s servant, Lucy, smuggle the American to a derelict tugboat moored in a nearby canal, which Jonathan struggles to get working again. Can they figure out how to operate the canal’s locks, and spirit the witch to safety — while contending with feral dogs, a violent bull, and superstitious villagers? And will Margaret join the group’s flight to France? Fun facts: I’ve long been a fan of the Changes trilogy, which includes The Weathermonger (1968) and The Devil’s Children (1970). Dickinson’s theme seems particularly relevant right now; someone should adapt the series for TV, don’t you think?

- Kin Platt’s supernatural/crime adventure Mystery Of The Witch Who Wouldn’t. This is a sequel to the entertaining, Edgar-award winning YA treasure-hunt adventure Sinbad and Me (1967), in which teenage friends Steve and Minerva unravel an 18th-century mystery in Hampton, Long Island — where Minerva’s tough-guy father is sheriff. (Sinbad is Steve’s English bulldog.) This time, Minerva begins to act strangely — as though she’s been hypnotized; and so does her family’s maid. Meanwhile, a time bomb nearly kills both Steve and the sheriff. With the help of his brainy friend Herk, Steve investigates the witch who wouldn’t — that is to say, a local sorceress who refuses to help criminals steal a local scientist’s secrets. The author has done his homework: We learn a lot about spellcraft and occult practices, not to mention a thing or two about Aleister Crowley. Demons are summoned! In the end, it’s up to Steve to rescue Minerva from a storm-ravagd harbor island… before it’s too late. An important part of this book’s charm, for me, is the lack of parental supervision: Steve, Minerva, and Herk do more or less whatever they please. Fun facts: Platt, who in the ’30s wrote radio comedy for George Burns and Jack Benny, and in the ’40s and ’50s wrote and drew now-forgotten comic books, also wrote a couple dozen mysteries under various pen names. He is perhaps best-known today, however, as author of one of my all-time favorite children’s picture books, Big Max (1965).

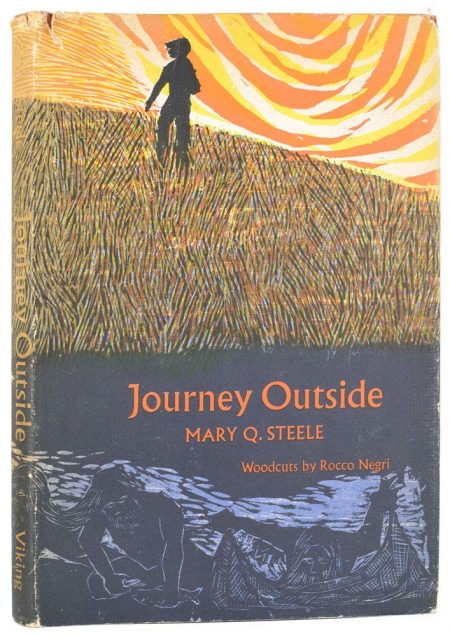

- Mary Q. Steele’s sci-fi adventure Journey Outside. Following in the tradition of sci-fi versions of Plato’s allegory of the cave — which begins, I think, with Gabriel De Tarde’s Underground Man (1884), and which was first introduced to younger readers, I think, by Suzanne Martel’s Quatre Montréalais en l’an 3000 (1963) — children’s author and naturalist Mary Q. Steele’s strange novella begins underground. Dilar is an adolescent boy whose tribe, the Raft People, float endlessly along a dark, enclosed river in search of a legendary world where fantasies like “green” and “day” are real. Suspecting, correctly, that they’ve just been traveling in circles, perhaps for generations, Dilar jumps ship — and discovers the outside world! He experiences unknown phenomena like sunlight, grass, and peaches for the first time… and is adopted by a community who, although living above-ground, also (it turns out) live lives that are meaningless. Dilar embarks on a journey to find his people and liberate them — but, again and again, he finds himself instead entangled in misguided ways of living. I suspect that Steele’s various communities — the People Against the Tigers, the cactus-sucking Not people, the man who spends his days cooking pancakes for animals — are intended as critiques of Sixties-era communes. It’s tough to tell — an odd tale! Fun facts: Nominated for the Newbery Medal in 1970, which was awarded to William H. Armstrong’s Sounder.

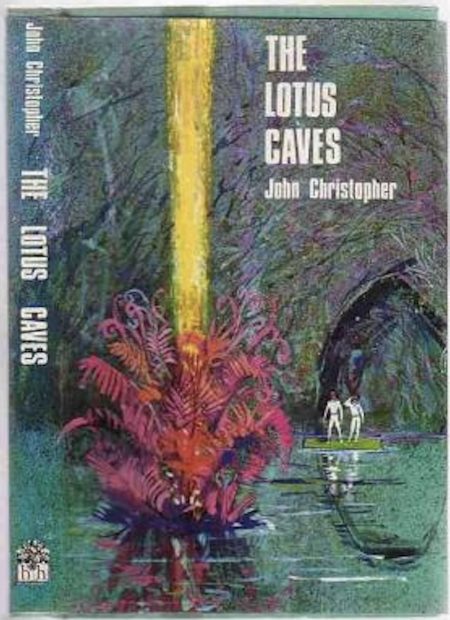

- John Christopher’s YA sci-fi adventure The Lotus Caves. One hundred years in the future, two teenage boys (Marty and Steve) hot-wire a lunar vehicle and explore the Moon’s surface — beyond the proscribed boundaries of “The Bubble,” their colony’s protected habitat. Following the trail of Andrew Thurgood, an early lunar settler who’d vanished 70 years earlier, Marty and Steve stumble upon a series of underground caverns populated by fluorescent plants — all of which turn out to be controlled by (and aspects of) an alien life form. So far, we’re in the realm of an old Robert Heinlein “juvenile,” like Red Planet, say — but things quickly get psychedelic. The alien being possesses the power to enthrall its captives, and maintain them in a blissed-out, timeless state for — well, forever. Can Marty and Steve escape the Lotus Caves — the book’s title refers to the land of the Lotus-eaters, which we read about in The Odyssey — and even if they can, why would they want to return to their boring, restricted lives inside the Bubble? Fun facts: Published between Christopher’s (Sam Youd) two great YA sci-fi series, the Tripods trilogy (1967–1968), and the Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1971–1972). Adapted as a freaky, campy Syfy TV pilot — High Moon — in 2014, by Bryan Fuller.

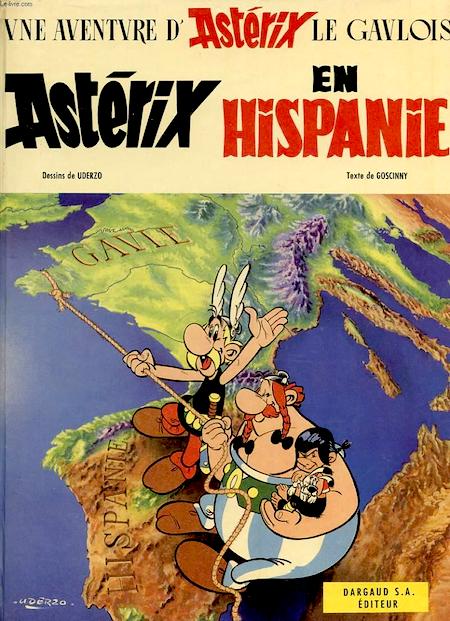

- René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s Asterix comic Astérix en Hispanie (Asterix in Spain; in English, 1971). In an effort to coerce Chief Huevos Y Bacon, heroic leader of a village of Iberian resistance fighters, Julius Caesar’s men kidnap the chief’s son Pepe and send him to Gaul as a hostage. There, however, Pepe — a disobedient and mischievous character in the tradition of O. Henry’s “Red Chief,” not to mention Herge’s Abdullah — is rescued by Asterix and Obelix, who are then assigned to return the boy to Spain. They are trailed by Spurius Brontosaurus, leader of Pepe’s Roman escort, who at first plots to recapture Pepe… but later, after he and Asterix accidentally invent the sport of bullfighting in Hispalis (Seville), decides to make his living as a toreador instead. As with Asterix and the Goths (1963), Asterix in Britain (1966), and Asterix in Switzerland (1970), among other Asterix travelogues, there are many jokes made at the expense of the national culture in question… in this case, Spanish pride, Spanish hot tempers, and the terrible condition of Spanish roads. The sub-plot in which the otherwise exasperating Pepe bonds with Obelix’ dog Dogmatix, to Obelix’s increasing dismay, is also a memorable one, to this fan. Fun facts: Serialized in Pilote magazine, in 1969. This is the fourteenth volume of the Asterix comic book series, and the first to feature Unhygienix the fishmonger; it’s also the first of many to feature a brawl between the Gaulish villagers.

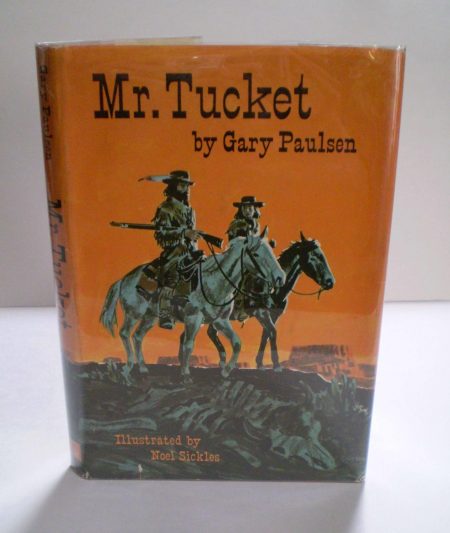

- Gary Paulsen’s Francis Tucket frontier adventure Mr. Tucket. Before Gary Paulsen was known as the Newbery Honor Award-winning author of YA survivalist novels like Dogsong (1985) and Hatchet (1987), he wrote this exciting, amusing, and also tragic Sid Fleischman-esque yarn about Francis Tucket, a 14-year-old who — while heading west on the Oregon Trail with his family — is abducted by Pawnees. Rescued by Jason Grimes, a one-armed fur trader who refers to his new sidekick as “Mr. Tucket,” Francis takes a crash-course in frontier survival skills. He learns to hunt rabbits and antelope, build a shelter against the elements, and — perhaps most importantly — eschew confrontation with potentially lethal enemies. Discretion, after all, is the better part of valor. Grimes is a no-nonsense mentor, whom Francis increasingly emulates… until a family is massacred, when we see a much darker side of the Jeremiah Johnson-esque mountain man. I wouldn’t call this a revisionist western, exactly; however, Grimes does make it clear to Francis that the Pawnee never attacked white settlers until their land began to be stolen; in fact, he encourages Francis to forgive and forget his own trials. Fun facts: In the sequel, Call Me Francis Tucket (published a quarter-century later in 1995), Francis attempts to reunite with his family… alone, this time. Other titles in the series include Tucket’s Ride and Tucket’s Gold.

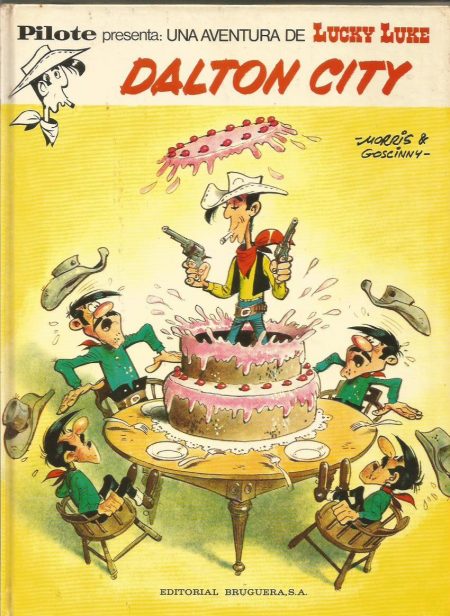

- Morris and Goscinny‘s Lucky Luke western comic Dalton City (serialized, 1969; in English, 1972). In their eighth appearance in the series, the Daltons — outlaw brothers Joe, William, Jack, and Averell — escape from prison. Their plan is to restore Fenton Town, a hotbed of depravity which Lucky Luke had previously shut down, to its former glory. Thanks to the hapless hound Rin Tin Can (Morris and Goscinny’s homage to Ron Tin Tin, canine star of a couple dozen 1920s movies), the Daltons capture Luke — and force him to play the role of a prospective guest in Dalton Town, prior to its grand re-opening. Once the Daltons hire singer Lulu Breechloader and her troupe of dancing girls, Luke persuades Joe Dalton that she intends to marry him. Thrilled, Joe plans a wedding and invites every desperado in the territory to attend. (The various outlaws dressed in their wedding finery were endlessly amusing to me, as a child.) Once Joe discovers that Lulu is already married, Luke must fight for his life. Fun facts: Serialized in Pilote magazine, this is the 34th Lucky Luke story. Morris and Goscinny were doing some of their best work around this time; I’m particularly fond of The Stagecoach (1968), The Tenderfoot (1968), Jesse James (1969), and Apache Canyon (1971).

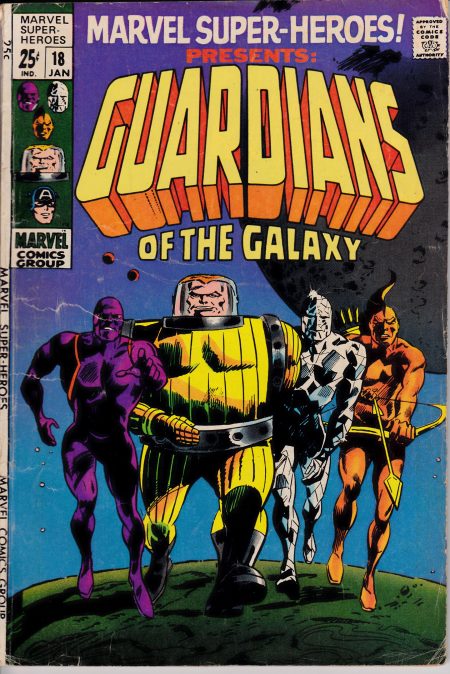

- Arnold Drake and Gene Colan’s sci-fi comic Guardians of the Galaxy (first appearance, 1969). Conceived of by Arnold Drake, who’d previously created the Doom Patrol for DC, and Stan Lee, the Guardians of the Galaxy are an all-for-one, one-for-all squad — originally composed of a Jovian super-soldier (Charlie-27), a crystalline Pluvian (Martinex), a primitive Centaurian (Yondu), and a psychokinetic mutant (Vance Astro, later known as Major Victory) — who’ve united against the threat, to their fellow humanoids on a far-future Earth, of the reptilian Brotherhood of Badoon. The Dirty Dozen-like team would appear and disappear from Marvel’s pages, in following years, landing their own series briefly in 1976, then making time-traveling cameo appearances in Thor, The Avengers, Defenders, and other titles through 1980 — written by Steve Gerber and drawn by Don Heck and Sal Buscema. Starhawk, who joins the team (in more ways than one), is an amazing character, too. Despite how grim and gritty Marvel became in the ’90s, the Guardians have remained a light-hearted, action-packed franchise. Fun facts: James Gunn’s 2014 superhero film Guardians of the Galaxy, and its 2017 sequel, were pretty fun — though not based on the early stories, which in 2009 were collected by Marvel into a single volume, Guardians of the Galaxy: Earth Shall Overcome.

- John D. Fitzgerald’s frontier adventure More Adventures of the Great Brain (ill. Mercer Mayer). In the first of several sequels to 1967’s The Great Brain, John D. Fitzgerald brings us back to Aden, a fictional Utah pioneer town in 1896 — and recounts Tom Sawyer-ish stories loosely inspired by his own experiences as an adolescent growing up in Price, Utah, in the nineteen-teens. Like J.D., the young narrator of these stories, Fitzgerald was the son of an Irish Catholic father and a Scandinavian Mormon mother; and he had a conniving but not entirely wicked brother, Tom. At the end of the first book, Tom (the self-proclaimed “Great Brain”) had seemingly reformed — i.e., by refusing to accept payment for helping the suicidal Andy Anderson adjust to his wooden leg, and by returning J.D.’s genuine Indian beaded belt. Tom is back at his old tricks again, however, in such yarns as “The Night the Monster Walked” (in which monster tracks, which appear to lead from Skeleton Cave to the river and back, lead to a panic), “The Taming of Britches Dotty” (about the transformation of a neglected girl; Tom teaches her to read, which is admirable — but his mother’s efforts to make Dotty conform to female gender rules is less so), and “The Death of Old Butch” (about Aden’s mourning of the death of a mongrel dog). Mercer Mayer’s illustrations are terrific. Fun facts: Subsequent installments in the series include Me and My Little Brain (1971), The Great Brain at the Academy (1972), The Great Brain Reforms (1973), The Return of the Great Brain (1974), and The Great Brain Does It Again (1976). A (lame) 1978 Great Brain movie starred Osmonds brother Jimmy.

- John Rowe Townsend’s YA thriller The Intruder. In my favorite John Rowe Townsend novel, the near-future YA thriller Noah’s Castle (1975), when a teenage boy finds his home transformed into a fortress, he must struggle — against centripetal and centrifugal forces — to decide for himself what the right course of action may be, even if that means defying paternal authority. This earlier novel, which is also a tense atmospheric thriller, finds our protagonist, 16-year-old Arnold Haithwaite, an adoptee driven out of his home by a creepy, manipulative stranger who claims to be the real Arnold Haithwaite, struggling with a similar predicament. The novel’s setting is very English — a nearly abandoned port town in England, inhabited by a few old-timers. Arnold makes a living guiding tourists across the silted-in harbor’s treacherous sands; as you can imagine, the sands (an a ruined church) become the scene of a dramatic chase and near-death experience, for Arnold and Jane, a love interest of sorts. Will Arnold learn the secret of his own identity — and stop the stranger from taking over his home? Fun facts: John Rowe Townsend (1922–2014) was not only a talented writer of many “juvenile” mysteries, but author of the definitive Written for Children: An Outline of English-language Children’s Literature (a 1965 survey, revised most recently in 1990). The Intruder, which won Edgar and Horn Book awards, was adapted as a fondly remembered 1972 British TV series.

BEST SIXTIES YA & YYA: [Best YA & YYA Lit 1963] | Best YA & YYA Lit 1964 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1965 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1966 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1967 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1968 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1969 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1970 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1971 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1972 | Best YA & YYA Lit 1973. ALSO: Best YA Sci-Fi.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.