LEAVE IT TO PSMITH (1)

By:

January 1, 2019

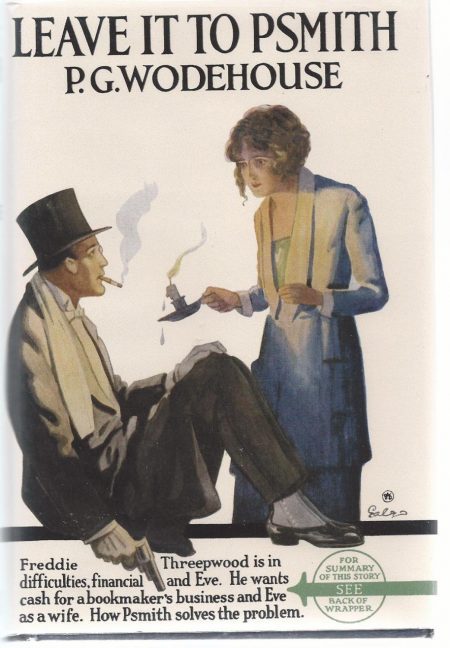

Leave It to Psmith (1923) is the last and most rewarding of four novels featuring the dandy, wit, and would-be adventurer Ronald Eustace Psmith, one of P.G. Wodehouse‘s most popular characters. (“One can date exactly,” Evelyn Waugh claimed, in reference to Psmith’s debut in the 1909 novel Mike, “the first moment when Wodehouse was touched by the sacred flame.”) Leave It to Psmith‘s copyright enters the public domain in 2019; HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this terrific book here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

At the open window of the great library of Blandings Castle, drooping like a wet sock, as was his habit when he had nothing to prop his spine against, the Earl of Emsworth, that amiable and boneheaded peer, stood gazing out over his domain.

It was a lovely morning and the air was fragrant with gentle summer scents. Yet in his lordship’s pale blue eyes there was a look of melancholy. His brow was furrowed, his mouth peevish. And this was all the more strange in that he was normally as happy as only a fluffy-minded man with excellent health and a large income can be. A writer, describing Blandings Castle in a magazine article, had once said: ‘Tiny mosses have grown in the cavities of the stones, until, viewed near at hand, the place seems shaggy with vegetation.’ It would not have been a bad description of the proprietor. Fifty-odd years of serene and unruffled placidity had given Lord Emsworth a curiously moss-covered look. Very few things had the power to disturb him. Even his younger son, the Hon. Freddie Threepwood, could only do it occasionally.

Yet now he was sad. And — not to make a mystery of it any longer — the reason of his sorrow was the fact that he had mislaid his glasses and without them was as blind, to use his own neat simile, as a bat. He was keenly aware of the sunshine that poured down on his gardens, and was yearning to pop out and potter among the flowers he loved. But no man, pop he never so wisely, can hope to potter with any good result if the world is a mere blur.

The door behind him opened, and Beach the butler entered, a dignified procession of one.

‘Who’s that?’ inquired Lord Emsworth, spinning on his axis.

‘It is I, your lordship — Beach.’

‘Have you found them?’

‘Not yet, your lordship,’ sighed the butler.

‘You can’t have looked.’

‘I have searched assiduously, your lordship, but without avail. Thomas and Charles also announce non-success. Stokes has not yet made his report.’

‘Ah.’

‘I am re-despatching Thomas and Charles to your lordship’s bedroom,’ said the Master of the Hunt. ‘I trust that their efforts will be rewarded.’

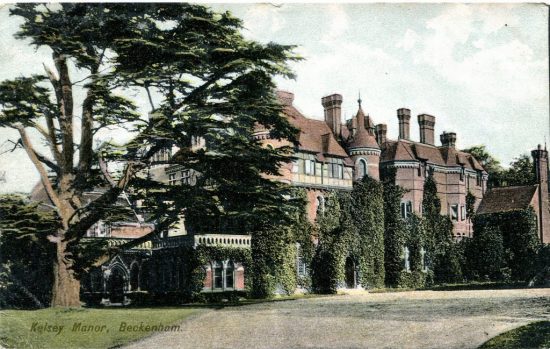

Beach withdrew, and Lord Emsworth turned to the window again. The scene that spread itself beneath him — though he was unfortunately not able to see it — was a singularly beautiful one, for the castle, which is one of the oldest inhabited houses in England, stands upon a knoll of rising ground at the southern end of the celebrated Vale of Blandings in the county of Shropshire. Away in the blue distance wooded hills ran down to where the Severn gleamed like an unsheathed sword; while up from the river rolling parkland, mounting and dipping, surged in a green wave almost to the castle walls, breaking on the terraces in a many-coloured flurry of flowers as it reached the spot where the province of Angus McAllister, his lordship’s head gardener, began. The day being June the thirtieth, which is the very high-tide time of summer flowers, the immediate neighbourhood of the castle was ablaze with roses, pinks, pansies, carnations, hollyhocks, columbines, larkspurs, London pride, Canterbury bells, and a multitude of other choice blooms of which only Angus could have told you the names. A conscientious man was Angus; and in spite of being a good deal hampered by Lord Emsworth’s amateur assistance, he showed excellent results in his department. In his beds there was much at which to point with pride, little to view with concern.

Scarcely had Beach removed himself when Lord Emsworth was called upon to turn again. The door had opened for the second time, and a young man in a beautifully cut suit of grey flannel was standing in the doorway. He had a long and vacant face topped by shining hair brushed back and heavily brilliantined after the prevailing mode, and he was standing on one leg. For Freddie Threepwood was seldom completely at his ease in his parent’s presence.

‘Hullo, guv’nor.’

‘Well, Frederick?’

It would be paltering with the truth to say that Lord Emsworth’s greeting was a warm one. It lacked the note of true affection. A few weeks before he had had to pay a matter of five hundred pounds to settle certain racing debts for his offspring; and, while this had not actually dealt an irretrievable blow at his bank account, it had undeniably tended to diminish Freddie’s charm in his eyes.

‘Hear you’ve lost your glasses, guv’nor.’

‘That is so.’

‘Nuisance, what?’

‘Undeniably.’

‘Ought to have a spare pair.’

‘I have broken my spare pair.’

‘Tough luck! And lost the other?’

‘And, as you say, lost the other.’

‘Have you looked for the bally things?’

‘I have.’

‘Must be somewhere, I mean.’

‘Quite possibly.’

‘Where,’ asked Freddie, warming to his work, ‘did you see them last?’

‘Go away!’ said Lord Emsworth, on whom his child’s conversation had begun to exercise an oppressive effect,

‘Eh?’

‘Go away!’

‘Go away?’

‘Yes, go away!’

‘Right ho!’

The door closed. His lordship returned to the window once more.

He had been standing there some few minutes when one of those miracles occurred which happen in libraries. Without sound or warning a section of books started to move away from the parent body and, swinging out in a solid chunk into the room, showed a glimpse of a small, study-like apartment. A young man in spectacles came noiselessly through and the books returned to their place.

The contrast between Lord Emsworth and the newcomer, as they stood there, was striking, almost dramatic. Lord Emsworth was so acutely spectacle-less; Rupert Baxter, his secretary, so pronouncedly spectacled. It was his spectacles that struck you first as you saw the man. They gleamed efficiently at you. If you had a guilty conscience, they pierced you through and through; and even if your conscience was one hundred per cent pure you could not ignore them. ‘Here,’ you said to yourself, ‘is an efficient young man in spectacles.’

In describing Rupert Baxter as efficient, you did not overestimate him. He was essentially that. Technically but a salaried subordinate, he had become by degrees, owing to the limp amiability of his employer, the real master of the house. He was the Brains of Blandings, the man at the switch, the person in charge, and the pilot, so to speak, who weathered the storm. Lord Emsworth left everything to Baxter, only asking to be allowed to potter in peace; and Baxter, more than equal to the task, shouldered it without wincing.

Having got within range, Baxter coughed; and Lord Emsworth, recognizing the sound, wheeled round with a faint flicker of hope. It might be that even this apparently insoluble problem of the missing pince-nez would yield before the other’s efficiency.

‘Baxter, my dear fellow, I’ve lost my glasses. My glasses. I have mislaid them. I cannot think where they can have gone to. You haven’t seen them anywhere by any chance?”

‘Yes, Lord Emsworth,’ replied the secretary, quietly equal to the crisis. ‘They are hanging down your back.’

‘Down my back? Why, bless my soul!’ His lordship tested the statement and found it — like all Baxter’s statements — acccurate. ‘Why, bless my soul, so they are! Do you know, Baxter, I really believe I must be growing absent-minded.’ He hauled in the slack, secured the pince-nez, adjusted them beamingly. His irritability had vanished like the dew off one of his roses. ‘Thank you, Baxter, thank you. You are invaluable.’

And with a radiant smile Lord Emsworth made buoyantly for the door, en route for God’s air and the society of McAllister. The movement drew from Baxter another cough — a sharp, peremptory cough this time; and his lordship paused, reluctantly, like a dog whistled back from the chase. A cloud fell over the sunniness of his mood. Admirable as Baxter was in so many respects, he had a tendency to worry him at times; and something told Lord Emsworth that he was going to worry him now.

‘The car will be at the door,’ said Baxter with quiet firmness, ‘at two sharp.’

‘Car? What car?’

‘The car to take you to the station.’

‘Station? What station?’

Rupert Baxter preserved his calm. There were times when he found his employer a little trying, but he never showed it.

‘You have perhaps forgotten, Lord Emsworth, that you arranged with Lady Constance to go to London this afternoon.’

‘Go to London!’ gasped Lord Emsworth, appalled. ‘In weather like this? With a thousand things to attend to in the garden? What a perfectly preposterous notion! Why should I go to London? I hate London.’

‘You arranged with Lady Constance that you would give Mr McTodd lunch to-morrow at your club.’

‘Who the devil is Mr McTodd?’

‘The well-known Canadian poet.’

‘Never heard of him.’

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.