10 Best Adventures of 1969

By:

December 24, 2018

Fifty years ago (as of 2019), the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Ishmael Reed’s satirical Western adventure Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down. Five years before Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles, the brilliant satirist, political philosopher, and prose stylist Ishmael Reed gave us this surrealist, provocative, fragmentary horse opera about the Loop Garoo Kid, a black circus cowboy, Neo-HooDoo houngan, and trickster who battles Drag Gibson, an evil capitalist rancher and tyrant of Yellow Back Radio, a Sergio Leone-esque ghost town. Along with Chief Showcase, a stylish Native American master of subversive survivalism, the Loop Garoo Kid also does battle with the oppressive and repressive elements of white Christian culture, which is to say, with pretty much every aspect of life as it is experienced by black Americans. Other antic characters include Bo Schmo, guru to a “neo-social realist” gang; Pope Innocent, God’s fixer; and Mustache Sal, a murderous mail-order-bride. Western myths are subverted (the novel’s title references the yellow covers of dime Westerns), obscenely. All of this takes place in a time warp, spanning three centuries of US history. Which, I suppose, makes Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down a sort of science-fiction novel, as well. Fun facts: Darryl Pinckney described Reed’s notion of Neo-HooDooism as “a literary version of black cultural nationalism determined to find its origins in history…. Neo-HooDooism, then, is a school of revisionism in which Reed passes control to the otherwise powerless, and black history becomes one big saga of revenge.”

- Kurt Vonnegut’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death. Much like the bumbling protagonist of Jaroslav Hašek’s pioneering antiwar novel The Good Soldier Švejk (1921–1923), Billy Pilgrim is an ill-trained, disoriented, cowardly chaplain’s assistant. During the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, he is captured and transported to Dresden. In 1945, as British and American bombers dropped several thousand tons of high-explosive bombs and incendiary devices on the city, Pilgrim and his fellow prisoners and their guards take refuge in a cellar beneath Schlachthof-fünf, the titular “slaughterhouse five”; they are among the only survivors of the (still-controversial) attack. We experience all of this in flash-backs or flash-forwards, because Billy has become “unstuck in time,” not to mention in space. At one point, years later, on his daughter’s wedding night, Billy is captured by aliens and transported to Tralfamadore, the fatalistic residents of which can observe all points in the space-time continuum simultaneously. Like them, Billy becomes a philosophical ironist because — thanks to his time-traveling — the entire human experience strikes him as absurd. Is he crazy, or a visionary? Fun facts: As a prisoner of war in 1945, Vonnegut experienced the Dresden firebombing; the narrator of Slaughterhouse-Five is the author, speaking in his own voice. The 1972 film adaptation, directed by George Roy Hill (in between directing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting), won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival.

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Left Hand of Darkness. This is the second of the author’s so-called Hainish Cycle, set in a galaxy whose human population evolved on Hain, then spread outwards to many other planets (including Earth) before, at some distant point in the past, losing contact. Efforts have been mounted to re-establish a galactic civilization; some eighty planets have organized themselves into a union called the Ekumen. In this novel, Genly Ai, an agent of The Ekumen, has spent a frustrating couple of years as an envoy to the frozen planet Gethen. Ai’s efforts to recruit Gethen into the Ekumen have failed… because his supposedly enlightened worldview is structured by binary oppositions. Gethenians, because they are ambisexual — they only adopt sexual attributes once a month, during a period of sexual receptiveness and high fertility — see the world in an entirely different way. Ai only begins to empathize with the Gethenian worldview once he escapes from prison with Estraven, an exiled Gethenian politician, who not only helps Ai survive a trek across the planet’s wintry wilderness, but helps him understand his own deep-seated prejudices and assumptions about gender and gender roles. Fun facts: The Left Hand of Darkness is one of the first feminist sci-fi novels, though some feminists have argued that it does not go far enough in critiquing gender stereotypes. Harold Bloom said, of this book, which won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards: “Le Guin, more than Tolkien, has raised fantasy into high literature, for our time.”

- Elmore Leonard’s Jack Ryan crime adventure The Big Bounce. Elmore Leonard’s first novels, published in the Fifties, were westerns. He wrote The Big Bounce, his first crime novel, in 1966, but couldn’t get it published until 1969, after it was adapted as the 1969 movie of the same title, starring Ryan O’Neal. When Jack Ryan, washed-up ballplayer and small-time thief, is hired as a Florida beach resort handyman, he’s quickly seduced by Nancy, a millionaire’s mistress who turns out to be something of a sociopath (or psychopath). Nancy wants Jack to steal a $50,000 payroll from her lover, and he goes along with the plan… which quickly gets complicated, of course. Nancy isn’t telling Jack everything; Jack, meanwhile, is being pursued by a couple of hoods to whom he owes money from his last caper. Readers who enjoy Leonard’s better-known novels, like Swag, Cat Chaser, Stick, LaBrava, and Get Shorty, may be disappointed by how unsympathetic our protagonists are, here; however, Leonard’s characteristic humor and laconic prose style are very much in evidence, as is his tendency to let his characters take the plot where they will — even at the risk of an ending that may not be entirely satisfying to most crime novel fans. Fun facts: The Big Bounce was adapted a second time — as a comedy heist film — in 2004 by George Armitage. Like the 1969 version, it was a flop. The character Jack Ryan would return in Leonard’s 1977 book Unknown Man #89.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Ubik. Joe Chip works for Runciter Associates, which employs “inertials” — telepaths and precogs with the ability to block the powers of other, less scrupulous telepaths and precogs — to protect the privacy of their clients. He’s one of Dick’s “minor men,” unable to manage his own life; in fact, he owes money to his own front door! Joe has a thing for his new colleague, Pat, who can change the past in such a way that people don’t realize it. Sent to Luna in search of criminal telepaths, Joe and Pat and the rest of their team is caught in an explosion… after which nothing is ever the same again. Are they moving backwards in time? Are they in some other reality? Are they caught up in a cosmic battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness — and if so, what is the ultimate source of these forces? Every interpretation that they posit is frustrated; meaning remains elusive. Each chapter is prefaced with an advertisement for Ubik, salvation in a spray can. This is, perhaps, the ultimate example of one of Dick’s apophenic sci-fi potboilers. Fun fact: Ubik inspired France’s Alfred Jarry-inspired Collège du Pataphysique to elect Dick as an honorary member. John Lennon, at one point, was interested in adapting the film version.

- Anne McCaffrey’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Ship Who Sang. Before Iain M. Banks’s (or Becky Chambers’ or Ann Leckie’s) independent AI starships there was The Ship Who Sang. Our protagonist is Helva, who was born with an exceptional brain and severe physical disabilities… so she was raised as an indentured servant destined to be a starship brain. One with a lamentable tendency to fall in love with her human co-pilot (known as the “brawn” to her “brain”) as they travel the galaxy on various missions of mercy. What happens if the brawn loves her back… and wants to have sex with her? Helva’s feelings of love and loss are poignant; however, the whole set-up is also a bit creepy and offensive! If you think about the sex scenes in McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series, you’ll begin to see why. Fun fact: The book’s first five chapters were originally published as “The Ship Who Sang” (1961; McCaffrey’s own favorite story), “The Ship Who Mourned” (1966), “The Ship Who Killed” (1966), “Dramatic Mission” (1969), and “The Ship Who Disappeared” (1969); the sixth chapter is original to the novel. In the 1990s, McCaffrey and co-authors produced six sequels.

- Vladimir Nabokov’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Ada, or Ardor. When he is fourteen, Van Veen, who will grow up to be a psychologist and renegade scholar, falls in love with his eleven-year-old cousin, Ada; they begin a life-long sexual affair, despite later discovering that they are half-siblings. The story begins in the early 19th century, though characters discuss airplanes, motion pictures, and other anachronistic technologies; everything is powered by water, and it is forbidden to mention electricity. Reference is made to an historical catastrophe referred to as “the L disaster,” which has somehow “everted” (I borrow the term from a 1975 essay about this novel in Science Fiction Studies) time, earth, and sexual gender. Van and Ada — who are maybe somehow, respectively, Eve and Adam — live on a planet known as Antiterra, which is geographically similar to Earth, although politically England has conquered most of it, and American culture is influenced by Russia. Nineteen-Sixties culture is, somehow, a myth from the past. Trippy! Fun facts: Ted Gioia has compared Ada to Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle and other alternate-history works of science fiction. I might include works by Samuel R. Delany and Michael Moorcock in which the Beatles become mythical figures.

- Jane Gaskell’s New Wave sci-fi adventure A Sweet, Sweet Summer. Enormous alien spacecrafts are hovering over London, Birmingham, and Manchester, sealing Britain off from the outside world; one of the aliens’ first demonstrations of power was the public execution of Ringo Starr. It’s a weird scene: “People rush under [the alien craft] when the rain starts so municipal authorities have erected seats and slot-machine arcades under them and charge you for using them.” The country descends into anarchy, as communist and fascist militias battle in the streets, and hoodlums terrorize the defenseless. Our narrator, Rat, is an unpleasant, misogynistic character who runs a tiny London boarding house and brothel. The alien invasion is the best thing that ever happened to him, so when his charismatic, gender-ambiguous, proto-punk cousin, Frijja, shows up and attempts to free London from alien oppression, Rat does what he can to thwart her — while also strugling to defend his turf from a marauding gang… with whose thuggish leader he is disturbingly fascinated. Fun fact: An exceedingly difficult book to find! China Miéville says that A Sweet, Sweet Summer “perfectly combines psychological perspicacity and social critique in an unusual dystopian future London.” Gaskell also wrote a seminal YA vampire novel: 1964’s freaky The Shiny Narrow Grin.

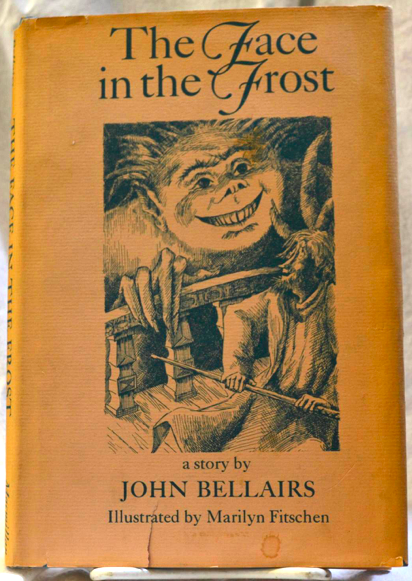

- John Bellairs’s fantasy adventure The Face in the Frost. When ominous supernatural phenomena come to the attention of Prospero, an accomplished but misfit wizard, he and his adventurer friend Roger Bacon head out to seek their source. There’s a slowly building atmosphere of menace, within a beautifully realized fantasy world of ghosts, chimaeras, and other nightmares. The elderly protagonists are a delight: sarcastic, crochety, courageous, given to spell-casting in allusive doggerel verse. The writing is gorgeous and full of sly anachronisms and meta-fictional references not only to Shakespeare and the “Cinderella” fairy tale, but to Lovecraft and Tolkien as well. The novella’s episodic plot feels like a Dungeons & Dragons adventure — there’s a haunted grove, a murderous innkeeper, weaponized weather, and a magical artifact that everyone’s after. In fact, Gary Gygax’s Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide lists The Face in the Frost as recommended reading; Prospero’s practice of studying his book of spells the night before he might need them no doubt helped inspired the game’s requirement for Magic Users to do so. Although Bellairs’s Lewis Barnavelt/Rose Rita Pottinger adventures are terrific, this is his only fantasy novel for adults. Fun facts: This is a fantasy novelist’s fantasy novel. Lin Carter praised The Face in the Frost as one of the best fantasy novels to be published since The Lord of the Rings. Ursula K. LeGuin described it as “authentic fantasy by a writer who knows what wizardry is all about.”

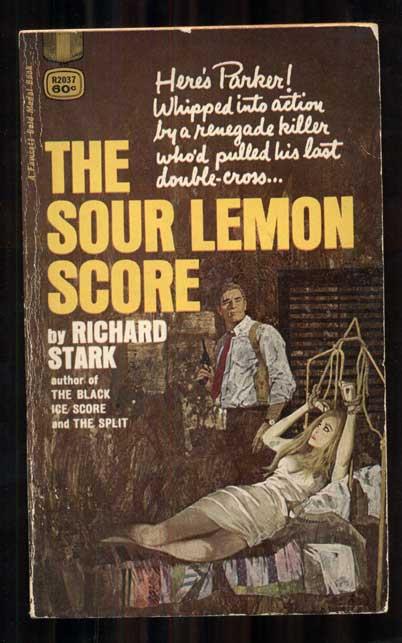

- Richard Stark’s Parker crime adventure The Sour Lemon Score. Parker’s twelfth outing is a return to form — in fact, it boasts more or less the same plot as the first Parker novel, The Hunter, though it’s quite a bit darker and more violent. The ruthless criminal Parker and three associates rob a bank, and make their getaway… but when the take is lower than they’d expected, George Uhl, whom Parker didn’t trust from the beginning, starts shooting. The caper has gone sour as a lemon, and the story now turns into a hunted-man adventure, with Parker in the role of the relentless hunter. Will Parker get his money back, punish Uhl, and make it home safely to Claire — the girlfriend he first met in 1968’s The Rare Coin Score? Maybe not! After all, Uhl is very good at hiding out… and there’s another dangerous crook, who gets wind of Uhl’s loot, for Parker to contend with as well. Fun facts: The Sour Lemon Score is one of five novels published in 1969 by the prolific Stark (Donald E. Westlake); the others are Somebody Owes Me Money, Up Your Banners (a race-relations comedy set in a New York public school), and The Dame and The Blackbird (both starring Alan Grofield, an actor and heist man who appears in some Parker novels). He’d publish another five novels in 1970!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.