STUFFED (30)

By:

December 23, 2018

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

Having smeared turkey for Thanksgiving, I thought it would be appropriate to belittle gingerbread for Christmas. I was initially planning to lament how a once great food, reserved by the King of France for professional bakers in Lyon (later Dijon) and regulated by guilds in Germany in the 16th century, had become a sad, homogenous, building material and ornamental anthropomorphic cookie. What food could survive being made into a building material? If we made meatloaf houses with hamburger shingles would be still love them? If we forced children to make little out-houses from cheez-its, would they still be a favorite snack of children and stoners alike? I think not.

As I scrutinized gingerbread history, however, I came to see it as a sort of feral dessert — one of the few long popular foods that had never been successfully domesticated. Maybe the gingerbread man himself was a sort of allegory for gingerbread’s ability to escape industrialization, ever running from the banal, bourgeois and rapacious masses intent on turning him into a product. Sure, he was a dope in the end, but better to be eaten than commodified. (Tucker Carlson, that miasma of dumb food takes floating across America like a bad fart, naturally had a segment on gingerbread cookie gender, arguing — did you have to ask — that they are gingerbread MEN goddamnit not gingerbread people and, accidentally, he may have a point this time — would a gingerbread woman have been taken in so easily by that fox?) And houses! How better to domesticate a recalcitrant treat than to build a house out of it? Really. If anything it was too on the nose, but I was willing to roll with it anyway.

But now I’m not so sure — and I’ll be honest, usually I just power through the “I’ve learned too much about this complicated topic to be pithy and reductive and, hopefully, humorous about it — why does everything get so muddled when you look at it carefully” stage of research. Here though, I’m at sea — gingerbread isn’t so much complicated as it is a complicated illusion. A trick, a mirage, an enigma wrapped in one of those other things inside another thing; a turducken made of lies. Turns out it’s a pile of different things, many don’t even have ginger, some are cookies, wafers, some are witch-influenced building materials, some purely decorative, many in between, and many are cake though with enough different ingredients that tracing commonality is far from obvious. But maybe there is something? When people say dog we all recognize that they could mean a wolfhound, a pomeranian, a basset or a bernard, right? Hairless dogs, barkless dogs, teacup dogs, mastiffs, there’s something, however gossamer, linking these disparate beasts together — right?

In China they’ve been eating honey-ginger bread for thousands of years. In Ancient Greece ginger flowed in through the trade avenues opened in Asia by Alexander the Great’s conquest and they made honey-ginger cakes — Rhodes was famous for theirs — and Hippocrates and Galen wrote of its health benefits. Cato (234-149 BC) and Apicius (1st century A.D. recording an older culinary tradition) both describe similar honey cakes called globi (honey cheese cake balls) and dulcia piperata (peppered honey cakes). The famous spiced wine ypocras (or hippocras) was made with ginger and other spices strained through a Hippocratics sleeve (a funnel shaped piece of cloth used as a filter) — it is one of the few early Medieval recipes to make it through the Renaissance. It fell on hard times for much of the 20th century, but seems to be making a — don’t call it a comeback. It was brought to Europe, like many things, during the crusades and slowly integrated into local cuisines.

But nothing was called gingerbread until much later and the reason is that it was a sort of linguistic hiccup. Ginger in Latin is giniber, gingebratum, in old/middle French gyngebraz, gingembras, gingimbrat, Middle English gingebrada, Old Occitan gingibrat, old Icelandic gingibráð, Middle Dutch gingebraes, gingebaers. Say those over and over again and it crosses over to gingerbread which is what they started calling preserved ginger and it was only much later when, presumably, someone wondered what was so bread-like about preserved ginger and they pivoted the use to ginger cakes and breads and other baked items. Even though the words trace through French, the French call their gingerbread pain d’épice — spice bread — but at least as long ago as the 14th-century bakers made both ginger wafers (gauffres — dough squeezed between hot irons) and gros bastons (literally big sticks) of ginger bread shaped like a blood sausage (all according to The Menagier de Paris, a 1394 cooking and shopping guide).

The 1324 Catalan cookery the Llibre de Sent Soví gives a recipe for salsa granada (grainy sauce) which is basically the ingredients of gingerbread with the flour replaced by chicken livers (ginger, cinnamon, cloves, sugar, egg yolks, chicken livers), the great early modern chef, Maestro Martino of Como (mid-15th century) gives a recipe for a Catalan ginger pottage of rice flour, milk, sugar, ginger, dates all cooked up together in a thick stew and served with chicken or (for Lent) pike and almond milk. At the end of the 16th century, French bakers in Rheims form a guild and convince the king to regulate what can and cannot be called pain d’épice (i.e. what they make can, everything else can’t — except at Christmas time where anyone can make gingerbread). Not too long afterward, the gingerbread center of France shifts to Dijon in what was no doubt a bloody internecine conflict. The finest French gingerbread dough back then would ferment for months or sometimes years, the honey in the dough collecting wild and feral yeasts which fermented into a sublime and difficult to replicate product. In the early 17th century, German bakers do much the same, forming a guild to regulate the German gingerbread trade. Right around this time you start to see both gingerbread people (all sorts of shapes, really — e.g. a gingerbread rooster wearing gilded pants was popular in the 19th century) and gingerbread houses (in Germany).

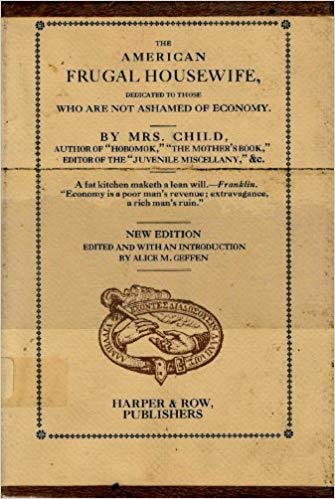

The 1663 English cookery A True Gentlewoman’s Delight has a spice cake of butter, currants, cream, mace, ginger, nutmeg, flour, eggs and it is around this time that England starts referring to this sort of thing as gingerbread more or less exclusively and they adopt the French custom of making shaped cakes/cookies that are eventually hawked by street-sellers (they even had a characteristic street cry — ‘Hot Spice Gingerbread, Smoking Hot!’). Though English gingerbread started more or less like the French — spices (not always including ginger), honey, some fermentation — it isn’t long before it goes its own way and the honey is replaced with treacle and in the U.S. most gingerbread is made with molasses from early on (a ca. 1700 manuscript suggests treacle, but printed cookbooks, beginning with the first in 1796, call for molasses). Lydia Child’s The American Frugal Housewife (1836) uses molasses with pearlash leavening (no yearlong fermenting here — pearlash is a baking soda) and she differentiates between hard and soft gingerbread. The great Philadelphia cookbook Miss Leslie’s Directions for Cookery (1837) breaks them up into white gingerbread (made with sugar), common gingerbread (with molasses), and gingerbread nuts (molasses and sugar formed into balls) all leavened with pearlash and adds Franklin cakes which are the same but leavened with eggs.

As gingerbread meandered down this path from royally privileged, slow fermented, honey infused, splendor to pearlash leavened cookie, it became increasingly gilded and richly adorned and in English the term gingerbread took on a variety of pejorative meanings: gingerbread work was nice looking but lousy, a gingerbread office was the bathroom, a gingerbread lord was someone who we might say was “all hat and no cattle”, the overly ornamented elements on many 19th century buildings in the U.S. were called gingerbread. To sum up, as gingerbread became degraded from the heights of its guild controlled quality, and as it became associated with building materials, witch houses (Grimm was published in 1812), and cheap street food, its use in language followed suit and that brings us to the present and the beginning where I thought I might drag gingerbread for Christmas — but I can’t do it.

What if gingerbread, whittled down to fancy, guild made perfection, is really all of these things it was whittled from: stew, sauce, cake, cookie, wafer, wine (and why not beer?), preserved ginger, ginger snap and witch house, dopey runaway and cock with pants? Since there’s no way to determine what authentic gingerbread might be, or even if it exists, and since gingerbread has been beat up and degraded, but is definitely not going anywhere, all we can do is reclaim the whole thousand year mess and call it gingerbread(s). After all, aren’t there enough exclusionary arguments these days? Is a taco a sandwich? Is ginger a bread? Short of asking Tucker Carlson, the safest, most inclusive thing to do is make them all gingerbreads, even the one made out of chicken livers — at the very least, like those French guilds, at Christmas time when the days are shortest and our hearts, supposedly, largest. Put all the gingerbreads around the tree, inedible, weird and wonderful the same.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.