The Poison Belt (Afterword)

By:

December 3, 2018

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Arthur Conan Doyle’s Radium Age sci-fi novella The Poison Belt (1913) in paperback form. Gordon Dahlquist, author of The Glass Books trilogy, provided an Afterword; his essay appears online for the first time now. Earlier this year, we also published Josh Glenn’s Introduction to our edition of The Poison Belt.

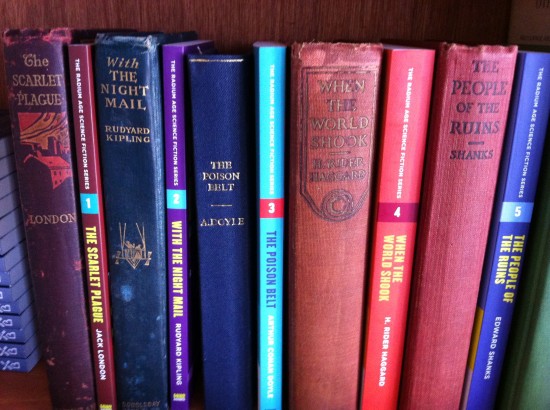

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

It’s impossible to read The Poison Belt, published in 1913, and not see in its exterminating vision a shadow of the coming war that would, only slightly less effectively, destroy Conan Doyle’s world. The effect is all the more powerful for the book’s deus ex machina ending (happy-ish, depending on one’s proximity to steam engines, lighthouses, or untended flames), which is one with that of War of the Worlds. Ultimate disaster is diverted through no power of man, and there but for the grace of Edwardian narrative decorum go everyone and everything. In both cases the unthinkable circumstance quite overwhelms the narrative fig-leaf, and vibrates in our imaginations like the after-image of a lightning bolt. The survivors’ expedition into London, past lines of fallen children, through smoking ruins, into corpse-choked city streets, evokes, as if Conan Doyle’s spiritualism had taken hold of his pen, images of Europe that have become emblems of the 20th century, but which in 1913 had no model. Who could conceive a capital of Europe being so depopulated, so beset? Not the least because such devastation is now stamped into our minds, a modern commonplace, do we see Conan Doyle’s more innocent society as a great steaming locomotive, first class carriages tricked out with gold, racing toward a broken bridge.

Obviously Conan Doyle has his own seat on that train. For every moment in The Poison Belt that reaches into the future, there is another blindly rooted in the past — or a present, as the present always is, defined by questionable convictions. So egregious are the book’s racist assumptions, as well as its blithe class discrimination — when even the life-time retainer doesn’t merit a place in the safe room — that they’re almost a tonic. One finds so much to love in this book, and so much darkness lurking behind its procedural banter, that to meet this unexamined stupidity as well is to confront — and to know, of course, inside — how history will judge our own self-satisfaction, our own moral expedience, our own blindness. I am happy to have him write it down, happy to see the cost of country mansions, the true foundation of empire. And I am thrilled that, in the end, for all his natural pride in human enterprise (for what else produces supermen like Challenger or Holmes?), Conan Doyle is cold-minded enough to lay our vanity bare.

The other point I’d like to make about The Poison Belt is how it is an early model of that now-familiar beast, the sequel. Though entirely diverting, The Poison Belt is inferior to The Lost World in every way, and despite its own cleverness exists mainly as a small monument to the earlier book’s more expansive (though equally imperial and troubling) delivery of pleasure. Where it makes sense that the strange collection of characters — journalist, sportsman, rival scientists — would fall together on an international jungle expedition, the only justification for their re-assembly in The Poison Belt is, explicitly, their previous success as a unit. This makes a different kind of story, where our investment is essentially sentimental, and where narrative serves two masters, familiarity as well as suspense. Moreover, once Challenger’s main insight has been explained, the characters are powerless. They wait and observe and submit. They venture out on a journey that, in our extrapolated imaginations at least, invokes the hellscapes of Bhopal, Dresden, Chernobyl — and then, having concluded that they can indeed do nothing, they drive home.

But this isn’t to say that Conan Doyle isn’t onto something. Who, from our vaunted future perspective, doesn’t do that same thing every single day?

APRIL — JULY 2012

Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the legendary detective Sherlock Holmes, also wrote a series of thrilling Radium Age science fiction adventures starring the brilliant, daring, obstreperous, and inadvertantly comical Professor Challenger.

“To anyone who has had the delightful experience of traveling in The Lost World with Professor Challenger the bare announcement that that brilliant and eccentric personage plays a most important part in this new tale will quite suffice. For who, having once met the Professor, would not desire to continue the acquaintance?” — New York Times (1913).

“It’s impossible to read The Poison Belt, written in 1913, and not see in its exterminating vision a shadow of the coming war that would, only slightly less effectively, destroy Conan Doyle’s world.” — Gordon Dahlquist (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.