With the Night Mail (Afterword)

By:

November 5, 2018

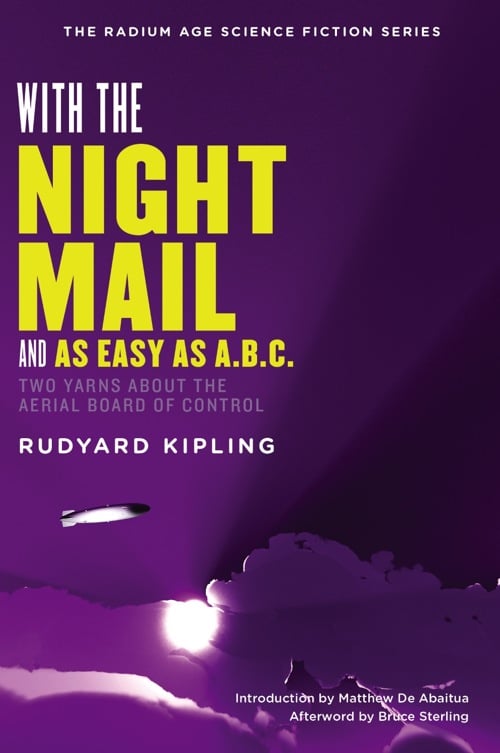

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Rudyard Kipling’s 1905 Radium Age sci-fi novella With the Night Mail (and the 1912 sequel “As Easy As A.B.C.”) in paperback form. Bruce Sterling, co-founder of science fiction’s cyberpunk movement and blogger at Beyond the Beyond, provided a new Afterword, which appears online for the first time now.

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

When Rudyard Kipling wrote these prescient and truly extraordinary stories, the term “science fiction” was still twenty years unborn. Why did Kipling do it?

The simplest answer is that Rudyard Kipling could publish anything he could dream up. During the golden period of these stories, 1905–1912, Kipling was about as famous as it was possible for a writer to get. The English public worshipped him. The American public admired him, even though he picked conspicuous fights with them. Mark Twain thought the world of him. Henry James was the best man at his wedding. Kipling had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature. If there were worlds left for him to conquer, they were in writing things that no previous writer could even dream about.

Kipling had already published some exceedingly well-received stories about steamships and railroads. Like most Kipling tales, these stories were crammed with snappy jargon, dramatic events and well- researched technical details. So why not take that writerly ability, and turn it to the topic of say, futuristic super-dirigibles? Everybody knew that flying airships were coming, because the newspapers in 1905 were full of that news. All it took was the boldness to make that conceptual leap.

All the snappy jargon would be faked. The dramatic events would be incredible happenstances that no human being had ever experienced, such as being wrapped in a big inflatable rubber air-suit and having a meteor remove your electrical charge. Even the technical details would be one long visionary parody of real-life technologies — mail delivery by a radium-powered aerial steamship-locomotive that could fly around the world.

And, having succeeded at that feat of invention, why not up the ante by teasing the magazine in which this story appeared? Do that by making up — cruelly parodying, even — the contents of the magazine itself. Would the editors print this arch, mocking, self-conscious contrivance — even though Kipling was making arrogant fun of the whole tiresome business of getting published in a magazine? You bet they would print any Rudyard Kipling story. And they cheerfully did.

Fame fertilized Rudyard Kipling’s eccentricities. This situation allowed him to anticipate science fiction. Rudyard Kipling, since his earliest youth, had been a notably eccentric guy. Although Kipling was alarmingly bright and even rather good-looking, he was also small, near-sighted and painfully sensitive to any trace of insult and disrespect. Fame therefore did him personal harm. Not because he gave into fame, but because he successfully fought it.

Kipling had married the sister of his American literary agent. Mrs. Kipling, a pragmatic and practical woman, knew rather a lot about the worldly worth of a successful writer of genius. When Kipling told her that he needed to be left alone in his study to work, she took this husbandly command with a lifelong seriousness. If Mr. Kipling wanted to be shut up alone in his office to dream and scribble, then in he would go, and in he would stay. Mrs. Kipling kept the prying world at bay — to the point of literally guarding her husband’s office door with her own desk.

Since Kipling had once been a boy reporter for British-Indian newspapers, he commonly passed for a hardbitten, commonsensical man of the world. All his stories play up this self-image, the greatest of Kipling’s many fictions. The Kipling narrator is always firmly on the side of our world’s practical, no-nonsense people: the engineers, soldiers, sailors, policemen, and bossy moms. Kipling was in fact a craft-friendly guy, and pretty good with his hands — his dad was an architectural designer, while his uncle was a Pre-Raphaelite painter. So Kipling knew his way around a workbench and an atelier. He genuinely enjoyed chatting with Edwardian steam technicians, who, by the way, were also his most loyal fans.

Kipling enjoyed the challenge of making fine literature out of the most rugged, resistant aspects of material life — cannons, pistons, cogwheels, bridges, trenchworks. Kipling knew that this engagement with industrial modernity cut him out of the pack — those brainy, hand-waving cliques of effete critics, philosophers, professors, politicians, and, well, most writers other than himself.

But Kipling, who was a genius and never a simple personality, was not some omnicompetent tough guy, but a near-sighted, prickly, jittery guy much given to ulcers and sudden nervous breakdowns. With his skyrocketing fancies and his fits of impulsive behavior, Kipling would have been one of the worst engineers or ship captains that one could imagine.

There aren’t any genuinely Kipling-like people in the entire works of Kipling. Even his own posthumous autobiography isn’t much like the real Kipling. The real Kipling was a desk-bound genius happily poring over arcane reference works while Mom brought in sandwiches. The real Kipling was a personality type that any modern science fiction fan would immediately recognize. He was your basic geek MENSA type, exceedingly bright, verbally fluent, polymathic and interested in literally everything, but hard-put to make any real friends. As he gets what he wants most from life — a workaholic splendor — he slowly drifts into a lonely isolation, and, with age, an ever-thickening political and social crankiness. Nobody can save mm from that fate, because nobody is smart enough to talk sense to him on his own level.

With the Night Mail is an amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius — Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s. Unlike Jules Verne (who was still beavering away on his own high-tech airship stories around 1905), Kipling doesn’t explain anything. Or rather, Kipling does explain, but every “explanation” is cunningly framed in terms of being something else — it’s a matter of money, a personal conflict, an illegal affront, an inside joke, a danger to shipping, a pretty curio. It’s anything but dry and boring exposition about how a future aircraft works. And yet you see the whole machine there, literally stem to stem.

Most interesting of all, the story isn’t even really a “story.” There’s scarcely a plot in it, and the characters are cardboard. With the Night Mail is “experiential futurism,” a phony piece of a future magazine to be encountered while opening a genuine magazine. With the Night Mail was originally inserted inside a real magazine, rather in the way that J.G. Ballard liked to make up fake ads in issues of Ambit in the 1960s. With the Night Mail is therefore a hoax and a put-on. It’s what postmodernists nowadays would call an “intervention.” It’s more than a mere work of popular fiction.

The profundity of this Kipling stunt doesn’t come across well in book form — our magazines, what’s left of them, no longer behave like his magazines. But it was exceedingly clever, the sort of thing that Verne or Wells would never have dreamed of doing. Even Robert Louis Stevenson couldn’t have done it. Mark Twain might have done it. Twain knew Nikola Tesla personally, and Twain still thought that Kipling was probably the smartest guy in the world.

“As Easy as A.B.C.” was something of a late sequel to Night Mail. It came along a full seven years later, after Kipling had worked with and gotten interested in historical change. “A.B.C.” is about politics, or, rather, it’s a visionary utopia where life has changed so much that politics are unnecessary. In the “easy” world of “A.B.C.,” everything is run by the practical technocrats whom Kipling professed to admire. Politics has died from lack of any sincere interest; there is no “society” any more, but only private individuals.

The Kipling of 1912 is as smart as the Kipling of 1905 but he’s in a much worse mood. “A.B.C.” shows a loathing of sociality — really an unfeigned, shrinking fleshy horror of large numbers of people all standing in the same place. Reclusive but world-famous celebrities are commonly bugged by such things. “Privacy” seems to be the only civil right that matters in this future world. Kipling figures that he’s making some terrific sense here, but he’s working through some of his own worst personal anxieties. They’re not pretty.

The persistent business about the hideous statue of the murdered black victim is especially unfortunate. Chicago’s cruelty to black immigrants in 1912 wasn’t any news to a perceptive observer from outside America. Kipling had married American and lived and worked in America. He’d watched Americans pirating his work for years. He enjoyed this chance to loudly talk about rope in the house of the hanged man.

“A.B.C” is a crazy-making story — it’s blatantly offensive in so many obvious ways, yet much more offensive once you start thinking seriously about its premises. What’s more, “A.B.C.” is mild stuff compared to another Kipling political provocation from the same period of his life, “The Mother Hive.” In “Mother Hive,” a royal sorority of sturdy, well-behaved talking bees are subverted, misled and destroyed by an evil feminist suffragette. “The Mother Hive” rehearses a number of cogent themes: racial decline, parasitism, secret cliques of breeding aliens, unthinkable intellectual perversions, gooey blind insect monsters, loathsome inbred degeneracy… that H.P. Lovecraft would champion twenty years later. “The Mother Hive” out-Lovecrafts Lovecraft, and is a much better political story than “A.B.C.”

However “A.B.C.” certainly has many strong merits as a work of science fiction. The greatest merit of “A.B.C” is that the world it extrapolates is truly weird. It’s so spacey that it’s in some sense timeless. It’s not a mere partisan fairy-story like “Mother Hive,” but a truly radical future scenario.

The future world of “A.B.C.” fails to divide neatly on any kind of analytical or left-right divide. Instead it has the true surreality of a society transfixed and dominated by its own unconscious upheavals.

“A.B.C.” is full of oxymorons, of contradictions in terms. If this world is properly run by level-headed international technocrats (as the story assures us that it is), then why is the human race dying out? Wouldn’t a practical person confront this issue, instead of languidly accepting it?

Why does the heroine of the story (at least, she’s the only woman with any say whatsoever) attempt to commit suicide? Why is this martyr-operation of hers considered such a great thing, and such a bracing gesture of authenticity? When the story’s political subversives are not killed (they expect to be killed) but instead, are turned into hugely profitable pop-culture stars — why is that a solution?

One might also note that this is a future society “without war.” Yet the story opens with a strange crisis that is very like a so-called “cyberwar” attack. “Illinois had riotously cut itself out of all systems and would remain disconnected.” The electrical power system is down, the roads and airports are closed. “All General Communications were dumb.” In 2012, we fully get it about riot—stricken regions cutting themselves off from the Internet. “A.B.C.” was written in 1912.

Consider the spooky non-lethal riot weaponry of the powers-that—be in “A.B.C.” — lasers, sonic weapons and some taser-like paralysis rays, all delivered from above, NATO air-power style. The actual “Aerial Board of Control” must have seemed pretty far-fetched in 1912, but nowadays the A.B.C. seems almost routine. It’s as powerful, as anonymous, as bored and as unhappy as the Internet Engineering Task Force. The IETF are another bunch of competent, responsible, international, Kiplingesque guys — just like the A.B.C., they are commonly complaining that they really didn’t want such an important job, and they don’t much know what to do with it.

The world of the Internet is wreathed in blazing controversy nowadays. Its technical masters, such as they are, come off like bright but detached people who would be far happier left alone in a studio, doing some genius coding. Boy, if only that would work out for us, hey? We can dream, can’t we?

Just let them get on with the real work at hand! That’s all they ask from the normal people! Just bring ’em a sandwich, that’s all they really need! A sandwich, and maybe this book.

MARCH — JUNE 2012

Rudyard Kipling was an English poet, prophet of British imperialism, and author of such immortal novels and stories as The Jungle Book, Kim, Just So Stories, and “The Man Who Would Be King.” He also wrote Radium Age science fiction.

“It is a glittering essay in the sham-technical; and real imagination, together with a tremendous play of fancy, is shown in the invention of illustrative detail.” — Arnold Bennett (1917)

“A most remarkable little story… It is rather a fascist picture which Kipling gives us.” — Norbert Weiner, The Human Use of Human Beings (1950)

“An amazing tour-de-force of inspired genius — Kipling, in 1905, is doing things that science fiction as a genre wouldn’t achieve until Robert Heinlein arrived in the late 1940s.” — Bruce Sterling (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.