10 Best Adventures of 1973

By:

October 16, 2018

Forty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- William Goldman’s meta-fantasy adventure The Princess Bride. Buttercup, a beautiful young woman, falls in love with her family’s farm hand, Westley — who leaves to seek his fortune so they can marry. When she hears that the Dread Pirate Roberts has killed Westley, a shattered Buttercup reluctantly agrees to marry Prince Humperdinck. En route to her wedding, she is kidnapped by a trio of outlaws (criminal genius Vizzini, fencing master Inigo Montoya, and enormous wrestler Fezzik), who find themselves pursed by a masked man in black. Everyone knows what happens next, of course — but let me just mention a few highlights: the man in black’s duel with the surprisingly honorable Montoya, his wrestling match with the surprisingly conscience-stricken Fezzik, his trek through the Fire Swamp with Buttercup, and his rescue — from Humperdinck’s torture chamber — by his former foes. The story ends with a series of mishaps and the prince’s men closing in, but the author indicates that he believes that the group got away. True love wins! Best of all, The Princess Bride is presented as “the good parts version” of a work by S. Morgenstern; throughout, the author — adopting the persona of a Hollywood screenwriter named Goldman — offers his own amusing running commentary. Fun facts: Goldman, who wrote the 1974 thriller Marathon Man, and who won Academy Awards for his Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and All the President’s Men (1976) screenplays, also wrote the screenplay for Rob Reiner’s beloved 1987 movie version of this book.

- George MacDonald Fraser’s sardonic Flashman Papers historical adventure Flashman at the Charge. In his fourth outing, Harry Flashman — antiheroic soldier, adventurer, and cad — is ordered to protect a young cousin of Queen Victoria’s during the Crimean War. Despite his best efforts to remain safely in England, Flashman finds himself at the Battle of Balaklava… where he accidentally assists the 93rd Regiment in routing a Russian cavalry charge — an incident later known as the Thin Red Line. What’s worse, he gets caught up in the Charge of the Light Brigade — a suicidal frontal assault on a well-defended artillery battery — and is captured! Imprisoned in Russia, Flashman encounters Harry “Scud” East (another character borrowed by the author from Thomas Hughes’s 1857 novel Tom Brown’s School Days) and a (real-life) vicious Russian operative, Nicholas Ignatieff. East insists upon escaping, in order to warn Britain of plans for the Russian invasion of British India…. This book used to be passed around as smut, in my high school; it’s certainly raunchy. Fun facts: This installment in the Flashman Papers is preceded by Flash for Freedom! (1971), in which our hero travels up the Mississippi with a fugitive slave and meets Abraham Lincoln. It is followed by Flashman in the Great Game (1975). Around this time, Fraser wrote the screenplay for the movie Royal Flash (1975), directed by Richard Lester and starring Malcolm McDowell.

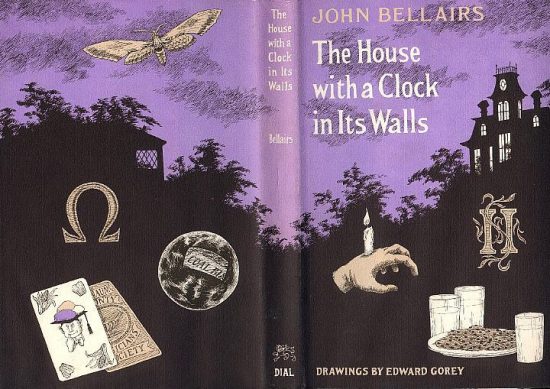

- John Bellairs’s children’s gothic horror adventure The House with a Clock in Its Walls. In the first of his many adventures, the recently orphaned Lewis Barnavelt moves in with his uncle, Jonathan, in a small Michigan town. Jonathan, a well-intentioned but not particularly powerful warlock, lives in a house formerly inhabited by Isaac and Selenna Izard, evil sorcerors who’d plotted to bring about the end of time. Before they died, Isaac had constructed a magical clock — hidden in the house’s walls — that ticks away as it attempts to pull the world as we know it towards its doom. In an effort to impress a new friend by demonstrating how to raise the dead, Lewis accidentally releases Selenna from her tomb; he must then enlist his uncle’s help — and that of their neighbor, Florence Zimmermann, a far more powerful good witch — in order to prevent Selenna from completing her husband’s dastardly work! Fun facts: The book, which was illustrated by Edward Gorey, was adapted into the 2018 Eli Roth film — starring Jack Black and Cate Blanchett — of the same name. Bellairs wrote subsequent Lewis Barnavelt adventures, including: The Figure in the Shadows (1975) and The Letter, The Witch, and The Ring (1976); other adventures in the same series were completed or written after his death.

- Susan Cooper’s YA fantasy adventure The Dark is Rising. On the Venn diagram showing admirers of Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising sequence and fans of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, I suspect there is little overlap — this, despite the fact that both feature a young English hero who discovers his magical abilities, then undertakes perilous quests in search of artifacts that will assist a rag-tag band of good wizards and witches facing the growing menace of supernatural evil. Cooper’s prose is superior to Rowling’s, but her stories are grimmer. In this installment, we meet Will Stanton, who until the eve of his eleventh birthday believes that he’s an ordinary kid. In fact, he’s an Old One — an immortal being who task it is to serve the Light, and protect the world from the Dark. In later installments, Will will join forces with the Drew siblings (whom we met in 1965’s Over Sea, Under Stone); here, he must travel through time seeking six magical talismans. He is assisted by Merriman, a decidedly un-Dumbledore-like mentor-wizard, and menaced by a sinister Rider and a mad Walker — not to mention a Hunter who represents neither Light nor Dark but wild magic. The mythological sub-strata can be a bit much, at times; and there isn’t a lot of swashbuckling action… or wizard battles, even. But it’s a marvelous, gorgeous tale — one of my favorite YA fantasy novels of all time. Fun facts: The Dark Is Rising sequence continues with Greenwitch (1974), The Grey King (1975), and Silver on the Tree (1977). The 2007 film adaptation of The Dark Is Rising (US title: The Seeker), directed by David L. Cunningham, is a disappointment.

- Alan Garner’s YA fantasy adventure Red Shift. In what is perhaps his formally most ambitious work, here Garner — author of the classic children’s and YA fantasy novels The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960), The Moon of Gomrath (1963), Elidor (1965), and The Owl Service (1967) — depicts a present-day England overlaid by a disintegrating (Vietnam War-like) Roman Britain. In fact, we’re reading three intertwined love stories, only one of which is set in the present. Tom, an unhappy teenaager, lives in a caravan park in Rudheath with his parents; as he loses his grip on reality, the story’s protagonist becomes Macey, a soldier in Roman Britain who, when berserk, fights with an old stone axe. Macy and his fellow deserters kidnap a local tribe’s corn goddess; and eventually get their comeuppance. Thomas Rowley, meanwhile, finds Macey’s axe head in a burial mound during the English Civil War; when their town is attacked by Royalist troops, Rowley and his wife flee to a new home — where they embed the axe head in the chimney. In the present day, Tom and his girlfriend find the axe head — will it bring them good fortune? Or disaster? Themes, visual descriptions and lines of dialogue echo throughout the text. Fun facts: Garner spent six years working on Red Shift, which he claimed was partially inspired by the Scottish legend of Tam Lin — where a boy kidnapped by fairies is rescued by his true love. David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas was likely inspired by Red Shift; at any rate, Mitchell has called Garner one of his favorite fantasy authors.

- J.G. Ballard’s sci-fi adventure Crash. If Ballard’s early novels — 1964’s The Burning World, for example — were sardonic inversions of survivalist cozy catastrophes, then Crash might be read as a sardonic inversion of another Adventure genre: the picaresque. In fact, the episodic, shambolic plot of Crash, in which the protagonist falls under the influence of a charismatic, wildly unconventional kook, and immerses himself in an automobile-centric world of transgressive kicks, feels to this reader like a pessimistic, avant-garde response to the all-American optimism of Kerouac’s On the Road. (Ballard himself described Crash as a “warning against that brutal, erotic, and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.”) In this anti-optimistic morality play, “James Ballard” is maimed in a car crash, which leaves the other driver dead; he is subsequently drawn into the orbit of Dr. Vaughan, a car-wreck enthusiast who heads up a kind of sex cult of fellow fetishists. Vaughan, Ballard, and others — Seagrave, a crossdressing stuntman; Gabrielle, a lesbian opium-addict and amputee; Helen, the widow of Ballard’s victim — engage in Sadean sex rites in crashed and about-to-be-crashed cars. If Ballard’s earlier novels are cataclysms set in the future; Crash takes place in a cataclysmic present, i.e., one in which catastrophe has become normalized. Fun facts: The Normal’s 1978 song “Warm Leatherette” was inspired by Crash; Gary Numan’s 1979 song “Cars” may have been, as well. In 1996, Crash was adapted as a film of the same name by David Cronenberg; it stars James Spader, Deborah Kara Unger, Elias Koteas, Holly Hunter, and Rosanna Arquette.

- Gerry Conway, Roy Thomas, and John Romita Sr.’s “The Night Gwen Stacy Died” story arc in The Amazing Spider-Man #121–122 (June–July 1973). If the cultural era known as the Fifties ended in ’63 with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, then the Sixties ended in ’73 with the death of Gwen Stacy. Harry Osborn, Peter Parker’s best friend, is addicted to drugs; parental grief causes Harry’s father, Norman, to snap out of his fugue state and remember not only that he is the Green Goblin, but that Peter Parker is Spider-Man. The Green Goblin kidnaps Peter’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, and lures Spider-Man to a New York bridge — then hurls Gwen off of it. Does Spider-Man’s attempt to save Gwen kill her? He certainly believes so. Readers were shocked: Important characters were not killed off; and superheroes did not fail in such a disastrous and tragic way. This story arc was a watershed event not only for Peter Parker. It marked the end of the Silver Age of Comic Books, which had kicked off in 1954 with the introduction of the Comics Code Authority; and it paved the way for the Bronze Age, which began in 1974 with the first appearances of Marvel’s dark, gritty characters Wolverine and The Punisher. Fun facts: During the Bronze and Modern Ages of Comics, the wives and girlfriends of superheroes began to drop like flies. In 2001, The Comics Buyer’s Guide revealed that within comics fandom this disturbing trend was known as “The Gwen Stacy Syndrome.”

- Poul Anderson’s fantasy adventure Hrolf Kraki’s Saga. What W.H. Auden once said of the author of the Lord of the Rings trilogy — “Tolkien is fascinated with the whole Northern thing” — is equally true of Poul Anderson, whose Scandinavian-inflected fantasy novels Three Hearts and Three Lions (1953) and The Broken Sword (1954) deserve to be (but are not) at least as well-known as his celebrated Golden Age sci-fi novels. Hrolf Kraki’s Saga is a multi-generational tale, pieced together from various sagas and elaborated upon by the author, which eventually features as its protagonist a legendary 6th-century Danish king. Hrolf Kraki assembles a band of warriors, including Bodvar Bjarki, a were-bear (!), and takes them along as he seeks recompense — from Adhils, King of the Swedes — for the death of his father. Although they survive rigged tests of their prowess, and open conflict with Adhil’s men, they offend Odin — and Hrolf loses his luck in battle. A few years later, when one of his sub-kings (aided by a half-elven witch) raises an army against him, will Hrolf and his men survive? Fun facts: First published, in paperback form, as an installment in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, edited by Lin Carter. Someone should make a movie of this yarn; the characters are amazing.

- Robert B. Parker’s crime adventure The Godwulf Manuscript. In 1971, ad man Robert B. Parker submitted his Boston University doctoral dissertation, “The Violent Hero, Wilderness Heritage and Urban Reality.” Two years later, he published this novel, the first to feature the private eye Spenser; in so doing, he breathed new life into the moribund American detective fiction genre whose passing his dissertation mourned. There’s no Hawk, no Susan Silverman, here — just a one-named private eye who used to box, likes to cook and crack wise, and sometimes butts heads with his former boss, Lieutenant Quirk of the Boston Police. When a medieval manuscript is stolen from a local university, Spenser suspects members of the Student Committee Against Capitalist Exploitation… then finds himself trying to clear the name of a young female radical whom he believes has been framed for murder. Not only is he fired from the case, he must come to grips with Boston mobsters and a shady professor — who runs away when Spenser takes a bullet for him, along the shore of Jamaica Pond! Fun facts: Parker would go on to write many other Spenser novels, including God Save the Child (1974), Mortal Stakes (1975), Promised Land (1976), and The Judas Goat (1978). The 1985–1988 TV show Spenser: For Hire was based on Parker’s Spenser series.

- Thomas Pynchon’s sci-fi picaresque Gravity’s Rainbow. Set during the waning days of WWII, Pynchon’s infamous masterpiece — considered by some to be one of the greatest American novels; considered by others to be unreadable — is an apophenic espionage adventure revolving around the quest to uncover the secret of a mysterious device, or MacGuffin, which is to be installed in a German V-2 rocket. (The book’s title refers to the parabolic trajectory of a V-2, as well as to the introduction of randomness into physics via quantum mechanics.) Gravity’s Rainbow is also a picaresque adventure, featuring over 400 characters, which follows Tyrone Slothrop, a naive Allied Intelligence operative, as he wanders — under covert surveillance, by his own comrades, who are interested in his sexual activities — around London, then a casino on the recently liberated French Riviera, and then in “The Zone,” which is to say, Europe’s post-war wasteland. What does Margherita Erdmann, former star of a traveling sado-masochistic sex show, know about the device? Why do the Schwarzkommando, African rocket technicians brought to Europe by German colonials, worship the V-2? Why is Slothrop being tailed by Major Duane Marvy, a sadistic American, and Vaslav Tchitcherine, a drug-addled Soviet intelligence officer? Slothrop discovers that he may have been experimented on, as an infant; does this have something to do with German occult warfare shenanigans? Plus: silly songs, 1940s pop culture references, kazoos. Here’s the key: “If there is something comforting — religious, if you want — about paranoia,” we read, “there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” Fun facts: Winner of the National Book Award for 1974, and nominated for both a Pulitzer Prize and a Nebula Award. A vast hermeneutical apparatus has developed around Gravity’s Rainbow… but you know what? It’s fun to read on its own, without any of the secondary literature!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.