Theodore Savage (Intro)

By:

September 4, 2018

In 2013 HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Cicely Hamilton’s Radium Age sci-fi novel Theodore Savage (1922) in paperback form. Gary Panter, whose artistic activity includes the science fiction comics Jimbo and Dal Tokyo, painting, prose, music, and light shows, provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

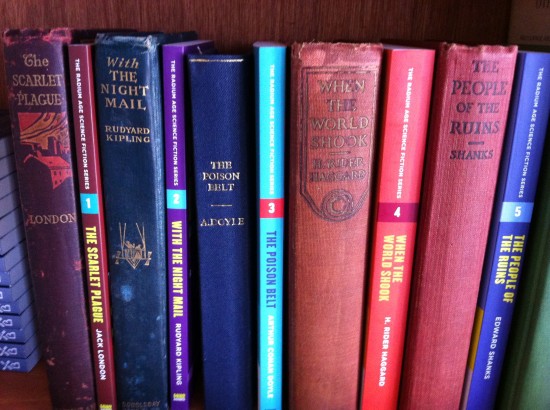

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

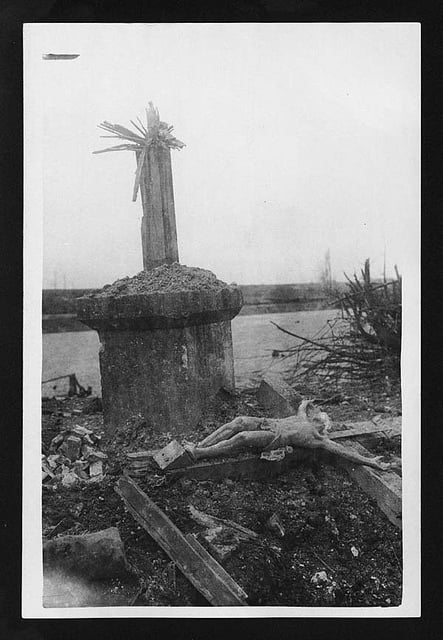

Published in 1922, just a few years after the Great War (a wretched conflict, also optimistically known as the War to End All Wars, featuring innovations in killing by aerial bombing and gas attacks), Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage: A Story of the Past or the Future is charged with the knowledge that terrible things, on a vast scale, which might change the very temper and tide of life as we know it, can happen. Even as the satanic mills of industry, the devilish ambition of nations, the endless appetite of the rich, and the fatal gullibility of the governed were pitching the world toward yet another devastating conflict, Hamilton took a cold look at humankind’s trajectory. Theodore Savage is one of a handful of early science fiction novels envisioning a future decline and devolution: a spark going out; a return to a new Dark Ages in which natural processes are untroubled by hope or aspiration; a numbing.

Human nature, one hears, has been formed over millennia by the never-ending battle between our instinct for life and reproduction, and our competing tendency towards death and stasis. Theodore Savage offers a trenchant critique, in its war-torn first chapters, of the death instinct’s triumph. However, the book’s final chapters, in which humankind no longer desires to achieve anything beyond its own brute existence, are an even more bleak and horrifying critique of the life instinct. Hamilton mourns in advance the possibility of a return to the Stone Age via the enforced dumbing-down of a people. The author’s voice is studied and sure as she describes the dismantling of British civilization and the extinction of modern man’s spirit of inquiry. Theodore Savage, the ironically named protagonist, is portrayed with studied detachment as a human creature who has entered a historical downgrade, plunging down an evolutionary regress into a frozen pool of limited possibilities.

Hamilton’s criticism of the English middle class is harsh and falls like a hammer again and again. A cipher of a guy, Savage is an educated civil servant with a predictable worldview. As civilization crumbles, he gains a distinguished world-weariness and ultimately a bit of faded godhead, but his averageness precludes him from ever turning the entropic tide. Lacking the spark that might permit him to lead a revolution back to his former life and prospects — back into twentieth century culture — Savage instead acquiesces in what might be described as a cargo cult in reverse. During World War II, the native peoples of Fiji and Papua New Guinea encountered high-finish, intricate manufactured goods delivered to their islands by Japanese and Allied aircraft. After the war, they attempted to keep these supplies flowing by ritually mimicking the behavior of their technologically advanced benefactors: e.g., they aped bureaucrats sitting at desks, wore makeshift business suits, and built jeeps and helicopters out of bamboo. In the postwar England of Theodore Savage, by contrast, the magic of modern science and technology becomes taboo. What Savage discovers is the spectacle of a civilized people ritually mimicking the habits of its own blue-painted ancestors: Swift’s Yahoos.

The over-riding theme of the book is the frailty of society and societal norms and niceties. For anyone who has been in a major disaster or experienced a black-out in a major city that goes on for a few days, the ticking clock of civility — relating to scarcity of water, food or goods, or to garbage collecting — and what we consider “basic normal,” is an awesome and sobering thing to see in action. At first everyone is polite and people pitch in, get in orderly lines, even party. Candlelit meals at restaurants where they give away free steak because it will spoil by tomorrow. But tomorrow: no free steak. And Hamilton is not considering some small breakdown of services, but the extermination of the mass of humanity.

Hamilton also demonstrates the efficacy of local peer pressure, which in her post-disaster England is the encompassing fist of the newly formed tribe’s militant myth enforcement. We are reminded that mindless orthodoxy is always and everywhere protected by those whose message is: Trust and Obey. Forty years before Philip K. Dick’s story “The Days of Perky Pat,” in which a stumbling nuked humanity plays with dolls in an escapist game that recalls an obsolete way of life, and in which one survivor is cast into outer darkness because he has introduced a taboo grown-up element into his clan’s purposely adolescent pastime, Hamilton gives us a similarly chilling scenario. Savage is interrogated by a group of fellow survivors who, like Cotton Mather and his enforcer cronies in colonial America, at first appear to be seeking to determine whether or not he has any helpful knowledge or skills to share. As it turns out, they are slyly testing him to make sure that he possesses nothing of the sort! Fortunately for Savage, like most of us educated future dwellers, his practical knowledge of anything science- or technology-related is minimal.

At the moment Hamilton was writing, the world order had gone viciously askew for years — costing tens of millions of lives, and millions more lives disrupted, forever maimed. People crawled out of the ruins, after the War to End All Wars, and rebuilt civilization… only to immediately develop newer, more horrifyingly efficient and far-reaching weaponry. The rapid evolution of industrial design in Hamilton’s lifetime must have been a dramatic thing — to see heavy, angular, black, hand- crafted machinery quickly give way to bullet-shaped, factory-fabricated, chromed machinery. From the Wright brothers to biplanes bombing villages didn’t take long. Hamilton could perhaps vividly envision an increase in the efficiency and dastardliness of the means that men invent and manufacture and sell and profit from for the purpose of killing others. If so, she was proven right.

Another contemporary problem that Hamilton, who was a journalist, suffragist, and lesbian, projects into the future is one that she’d described, in a cynical 1909 book of this title, as “marriage as a trade.” Writing at the height of the suffrage struggle, Hamilton stripped away what she regarded as the sentimental nonsense surrounding marriage. For women, whose economic opportunities were limited by law and custom, marriage was the primary way to earn a living — and nothing more. Worse, because men want women to be unthreatening creatures, females are raised with only one commandment: “Thou shalt not think.” Perhaps Hamilton’s criticism of modern marriage and women explains the brutal portrayal, in Theodore Savage, of Ada — Theodore’s Girl Friday. Like Burgess Meredith’s character in the Twilight Zone anti-cozy catastrophe episode “Time Enough at Last,” Savage has miraculously survived a civilization-shattering war only to find himself burdened rather than liberated. Ada, the Eve to his Adam, is stupid, vain, shallow, dull, mulish, slatternly, weak, obsequious, groaning, unhygienic. Though all social and cultural norms have been dissolved, fate or the roll of the dice dooms Theodore and Ada to a traditional marriage of the worst sort.

Ada frequently gets slapped around, as an incitement to get a grip — like a hysterical dame in the Tarzan and cowboy movies common when I was a kid. This is a shocking state of affairs to the sensitive reader here in the present/future, when we don’t slap women around anymore, do we? Actually, come to think of it, a lot of women are being slapped around and worse right at this civilized moment all around the world — a time when in some places, girl’s schools are burned and female students are murdered to intimidate populations of women who dare to be curious or active; and in other places female babies are aborted, abandoned, mutilated for some guy’s reason, or murdered out of cultural preferences for male progeny. By writing scenes in which Ada was abused, was Hamilton reminding us of how bad women have it? Or was she perhaps demonstrating contempt for those weak and idle women who were the suffrage movement’s fiercest critics? It’s hard to decide; she presents us with a nice sticky ball of wax.

These days, fictional dystopias and after-the-apocalypses are many, and they play endless subtle variations on our collective hopes and dread. During science fiction’s midcentury Golden Age, many authors took a mutant-thumping pleasure in depicting the end of civilization and its wake. However, in Hamilton’s deliberately plotted novel from the genre’s Radium Age, civilization’s downward slide isn’t a wild roller-coaster ride — e.g., like Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer. Nor is there any last-minute “soft landing” redemption — e.g., as in John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids. Instead, the book’s story arc is as stately as wax falling away from the light of the candle.

MARCH 2013 — AUGUST 2013

Cicely Hamilton (1872–1952) was an Anglo-Irish novelist, dramatist, and campaigner for women’s rights who served during WWI with an ambulance unit and at a military hospital in France. Her plays include Diana of Dobson’s (1908) and How the Vote was Won (1909); her 1909 treatise Marriage as a Trade is a witty criticism of that institution. The dystopian Theodore Savage is her only science fiction novel.

“Like Colson Whitehead’s Zone One without the zombie camp and idiom, Theodore Savage is a dark, strange, and cruelly contemporary tale of The Ruin and the post-apocalyptic condition that follows,” says Alexis Madrigal in a 2013 blurb for HiLoBooks. “The book makes a spirited argument against science and machines, disputing itself viciously to the last word.”

“Miss Hamilton always writes forcibly, and her present novel deals with the heart shaking effects of the next war. It might, indeed, be used as a tract to convey an awful warning.” — The Spectator (1922)

“A particularly effective and chilling version of a theme that dominates British speculative fiction between the wars.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed.

“Hamilton is one of the first — and among the darkest — of those UK novelists whose vision of things was shaped by WWI, which they saw as foretelling the end of civilization.” — The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Clute and Nicholls, eds.

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.