10 Best Adventures of 1958

By:

August 31, 2018

Sixty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Forties (1944–1953) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Note that 1958 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Fifties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Fifties; the titles on my 1958 and 1959 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Fifties adventure writing is all about. That is, morally ambiguous — yet suspenseful, exciting — espionage adventures, as well as some of the greatest caper crime adventures ever written. Plus, the Golden Age of science fiction.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

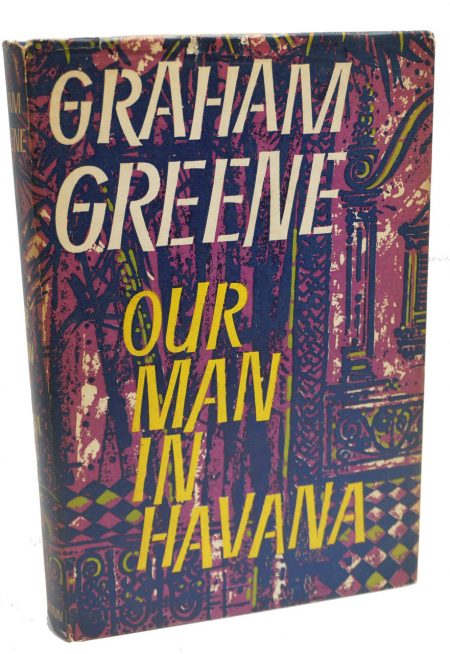

- Graham Greene’s sardonic espionage adventure Our Man In Havana. This black comedy set in (pre-Missile Crisis) Cuba, which Greene considered an “entertainment” rather than one of his serious novels, mocks the willingness of intelligence services to believe reports from local informants. Hard-pressed to satisfy his teenage daughter’s expensive tastes, Wormold, who owns a Havana vacuum-cleaner shop, begins selling invented information about agents and government installations (actually sketches of vacuum cleaner parts) to Britain’s MI6. Havana’s tawdry side is brought to life vividly, and the Batista regime is a chilling backdrop. When the real-life model for one of his imaginary agents is killed in apparent accident, Wormold must attempt to save the real people who share names with his fictional agents. Soon enough, an Soviet agent is assigned to assassinate Wormold himself… at which point, our man in Havana begins scheming to get his hands on an actual list of all of the spies in Havana — from Batista’s chief torturer. Fun facts: The book was adapted by Carol Reed as a 1959 movie of the same title starring Alec Guinness. PS: Greene was recruited by MI6 during World War II, and worked in counter-espionage in the Iberian Peninsula, where he had learned about greedy German agents in Portugal sending the Germans fictitious reports.

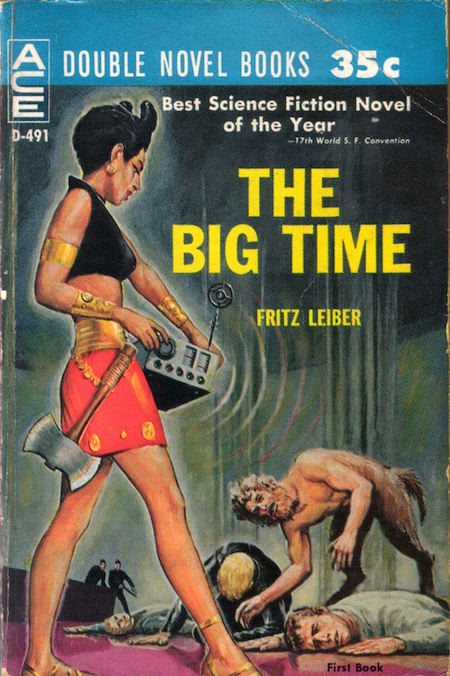

- Fritz Leiber’s sci-fi adventure The Big Time (serialized 1958; in book form, 1961). The Big Time is a far-out example of what I have elsewhere called the Crackerjack sub-genre of adventure — in which consummate professionals team up for a common purpose. (An immediate predecessor is, for example, The Guns of Navarone [1957].) Here, however, our crackerjacks are ten warriors from various eras of Earth and non-Earth history: e.g., Marcus (ancient Roman), Erich (Nazi), Kaby (female warrior from ancient Crete), Sevensee (satyr from the far future), not to mention Ilhilihis (octopoid extraterrestrial from the Moon’s distant past). Each of these characters was snatched out of his or her own time at the moment of his or her death, and shanghaied into the service of alien factions — known colloquially as the Spiders and the Snakes — who send them into battles across time and space, in an ongoing effort to alter the course of history. The so-called Change War, with its Stapledonian cosmic, era-spanning sweep, is merely a backdrop, however, to Leiber’s Sartrean chamber drama, which is set in a neutral Valhalla-like (it’s removed from the “little time” of history; hence the novella’s title) recuperation station for time warriors. Here, characters fall in and out of love, make speeches, and… deal with a time bomb set ticking by a saboteur! Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy (March–Aril 1958). Winner of the 1958 Hugo Award — though it’s a very controversial Hugo winner. The terrific Hasbro boardgame Heroscape (2004–2010) seems directly influenced by this book.

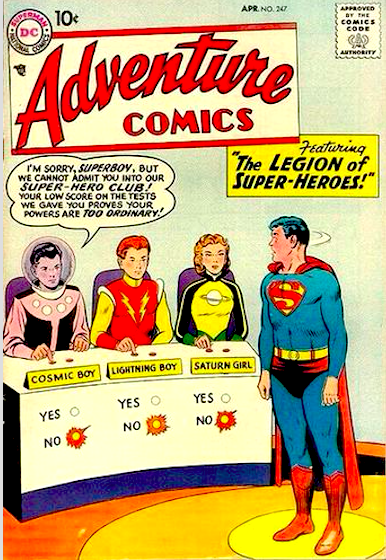

- DC Comics’ sci-fi adventure series The Legion of Super-Heroes (1958–on). When I was an adolescent, I couldn’t get enough of Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes (1977–1980, written by Paul Levitz/Gerry Conway, drawn by James Sherman); I’d also scour flea markets and comic shops for copies of the Legion’s previous series, Superboy starring the Legion of Super-Heroes (1973–1977), as well as Sixties-era copies of Adventure Comics featuring LSH stories. The Legion — the Silver Age of comic books’ first superhero team, created by writer Otto Binder and artist Al Plastino — first appeared in a 1958 issue of Adventure Comics, in which Lightning Lad, Saturn Girl (a telepath from Titan), and Cosmic Boy (who can generate magnetic fields) travel back in time from the 30th century in order to recruit Superboy. For the next two decades, the LSH would prove enduringly popular, thanks largely to fun characters like Chameleon Boy, Star Boy, Triplicate Girl, Bouncing Boy, Dream Girl, Ferro Lad, Matter-Eater Lad, Princess Projectra, Shadow Lass, Timber Wolf (who surely helped inspire Marvel’s Wolverine), Wildfire (a being of pure anti-energy), and — perhaps my favorite Legionnaire — the green-skinned, unstable genius Brainiac 5. I prefer the dissensual late-1970s version of the team; but the Mickey Mouse Club-like pre-Sixties LSH has its charms too. Fun facts: I can’t say that I’m crazy about post-1980 LSH reboots, threeboots, or retroboots. However, I did enjoy Mark Waid and Barry Kitson’s 2006–2008 run of Supergirl and the Legion of Super-Heroes, which was the temporary title of the Legion of Super-Heroes (Volume 5) from issues #16 to #36.

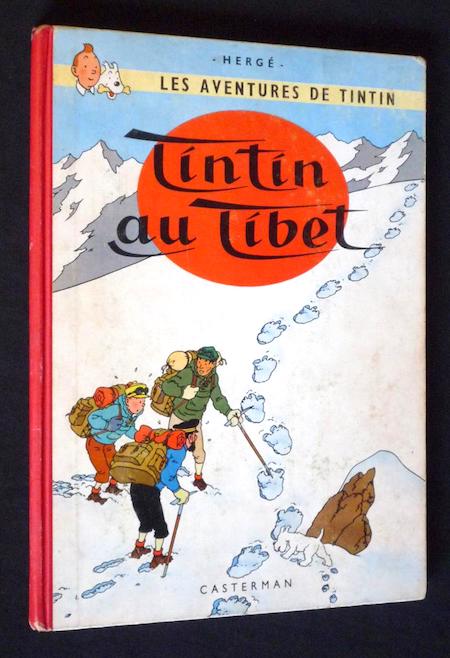

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure Tintin au Tibet (Tintin in Tibet, serialized 1958–1959; as an album, 1960). In his 20th outing, Tintin envisions his friend Chang (a Chinese boy who’d helped him out in The Blue Lotus), injured and calling for help from the wreckage of a crashed plane in the Himalayas — is it just a dream? No matter, Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Snowy immediately fly to Kathmandu, hire a sherpa and porters… and begin a hazardous trek towards the plane’s crash site. Mysterious tracks frighten off the porters, who believe that the abominable snowman who figures in the Himalaya people’s ancient legends and folklore is actually out there. While scaling a cliff face, Haddock slips and nearly kills Tintin; then, they lose their tent. Tintin sends Snowy to a nearby Buddhist monastery of Khor-Biyong for help… just before an avalanche hits. Is this the end of the Tintin saga? Fun facts: This was one of Hergé’s favorite Tintin stories; and the Dalai Lama awarded it the Light of Truth Award — because, he believed, Tintin in Tibet helps promote democracy and human rights for the Tibetan people.

- Robert Heinlein’s sci-fi adventure Have Spacesuit — Will Travel (1958). Having entered an advertising jingle writing contest on a lark, high-schooler Kip Russell wins a functional, but obsolete spacesuit. Although there’s no chance he’ll ever go to space, or even to one of Earth’s Moon colonies, Kip determinedly repairs and refurbishes the suit… and takes it out for a stroll. At which point, a UFO materializes. A young human girl, “Peewee,” who is the daughter of an eminent scientist and a genius herself, and an alien creature, which Peewee calls “the Mother Thing,” are on the run from another alien species. All three are captured by the horrific baddies (Kip dubs their leader “Wormface”) and taken to the aliens’ secret base on the Moon. From there, they travel to Pluto, and then Vega 5, the Mother Thing’s home planet; at every step of the way, Kip does his best to rescue his new friends. As if all this weren’t epic enough, in the end Kip and Peewee must intervene with an intergalactic tribunal on behalf of their planet! Fun fact: During World War II, Heinlein was a civilian aeronautics engineer working at a laboratory where pressure suits were being developed for use at high altitudes. Have Spacesuit — Will Travel is the last of his “juveniles” — sci-fi books for young readers. Serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

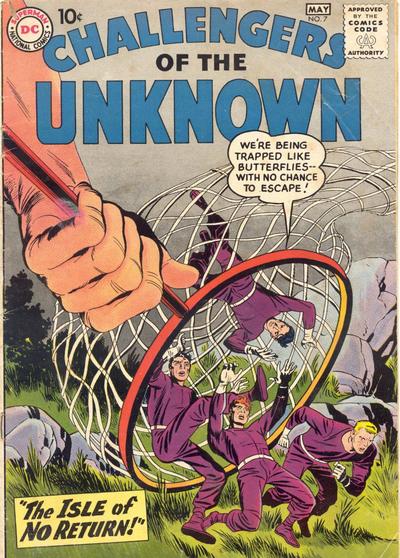

- Jack Kirby‘s pre-Silver Age sci-fi adventures (c. 1958–1961). Shortly before he and Stan Lee began their extraordinary run at Marvel Comics, capitalizing on a revived interest in superhero storytelling and revolutionizing the industry with The Fantastic Four (1961) and other titles, Jack Kirby spent three years freelancing for DC and Atlas — during which time he drew hundreds of pages of sci-fi comics. With writers Dick and Dave Wood, he co-created the Challengers of the Unknown, a quartet of jump-suited adventurers who investigated science fictional and apparent paranormal occurrences; the team — pilot Kyle “Ace” Morgan, daredevil Matthew “Red” Ryan, strong and slow-witted Leslie “Rocky” Davis, and scientist Walter Mark “Prof” Haley — is a precursor to The Fantastic Four. In the pages of DC’s Adventure Comics and World’s Finest Comics, Kirby recast DC’s Green Arrow as a science-fiction hero, complete with an Arrowcar and Arrowplane. Perhaps most importantly, during this period Kirby drew dozens of sci-fi and sci-fantasy stories (such as “I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers”) for Amazing Adventures, Strange Tales, Strange Worlds, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, World of Fantasy, and other anthologies such as DC’s House of Secrets, House of Mystery, and My Greatest Adventure. His monster stories, in particular — for example, Groot, the Thing from Planet X; Grottu, King of the Insects; Fin Fang Foom — are extremely fun.

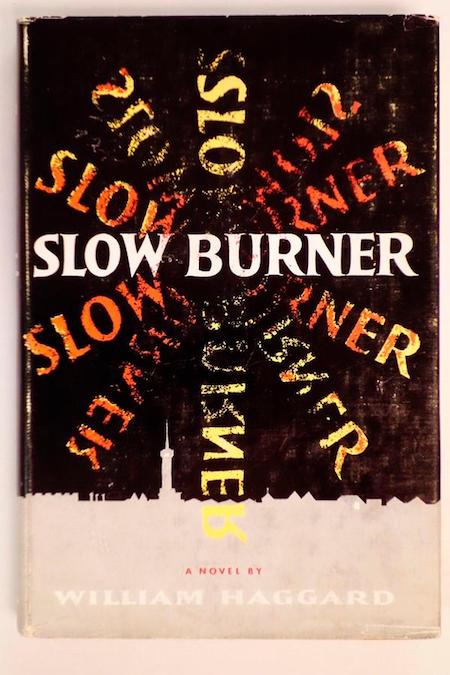

- William Haggard’s Colonel Charles Russell espionage adventure Slow Burner. In his debut outing, we meet Colonel Charles Russell — chief of the Special Executive, a (fictional) British counterintelligence service; the man who gives orders to field agents, that is to say; he is not himself an agent. Although there is some bang-bang action, here, Russell is primarily concerned with political maneuvering: Personal antagonisms within Britain’s intelligence community eventually lead to murder. At the same time, there’s a slow-burning plot-line about a British scientist selling top-secret military tech. Here we meet for the first time not only Russell but his assistant, Major Mortimer; Sir Jeremy Bates, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry; and Russell’s friend, the eminent scientist Dr. William Nichol, who directs a project developing a secretive nuclear fission process known as Slow Burner. Why are epsilon rays — the signature emission of the Slow Burner process — emanating from a suburban home outside London? Mrs. Tarbat, who lives in the house in question, has three lovers — is one of them a traitor? Charlie Percival-Smith, a disavowable third party, is brought in to investigate…. And there’s a frantic attempt, near the end, to prevent a nuclear accident near Oxford! Fun facts: Colonel Russell would go on to feature in a further 24 novels. “Haggard lacked [Ian] Fleming’s snooty dilettantism,” Christopher Fowler has written, “and was better at creating subtle layers of political intrigue.”

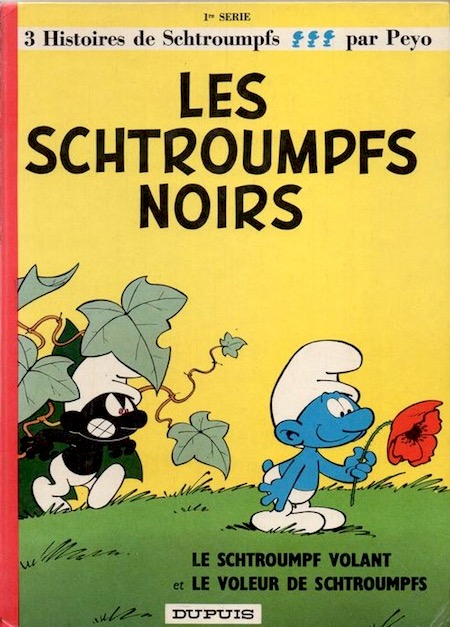

- Peyo’s fantasy adventure comic Les Schtroumpfs (The Smurfs, serialized 1958–1992). Forget the silly, often insipid 1980s Hanna-Barbera cartoon show, the unwatchable live-action/computer-animated movies from the 2010s, and the star-studded 2017 movie Smurfs: The Lost Village; forget the videogames, the songs, the toys and the theme parks. The Smurf comics from the ’60s and ’70s, created by the Belgian cartoonist Peyo, are actually pretty great. Hefty Surf, the tattooed strongman; Grouchy Smurf, the misanthrope; Clumsy Smurf, the dimwit; Jokey Smurf, the prankster; Vanity Smurf, the narcissist; Gargamel, the human sorceror who needs to catch a Smurf in order to create a philosopher’s stone; Papa Smurf, the tribe’s wise leader; and Smurfette, created by Gargamel to sow discord among the Smurfs… it’s an entertaining cast of characters, a young kids’ version of the Gaulish village created by France’s René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. (My only complaint is about Brainy Smurf, who’s just a jerk with glasses.) The Smurfs’ adventures — including a zombie apocalypse (Les Schtroumpfs noirs, serialized 1959), the rise of a proto-Trumpian populist would-be strongman (Le Schtroumpfissime, serialized 1964), the menace of a monstrous Howlibird, and a faked Moon landing — hold up well. Just be careful to avoid the many post-Peyo Smurfs comics. Fun facts: Peyo introduced the Smurfs in Spirou magazine, to which he contributed the series Johan and Peewit (1947–1977). The Smurfs got their own story in 1958, and were an immediate hit with readers.

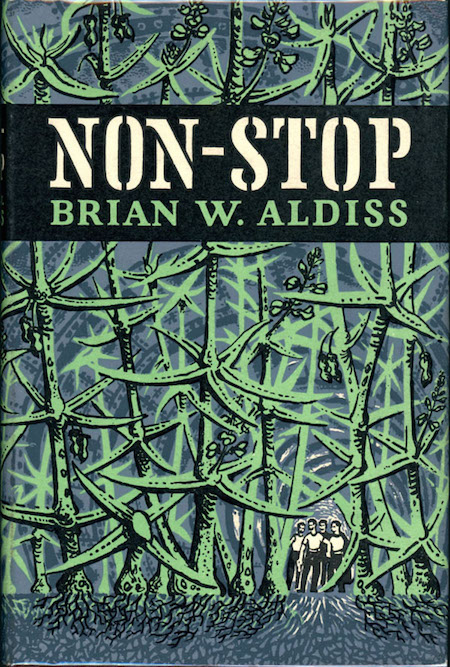

- Brian Aldiss’s sci-fi adventure Non-Stop (also published as Starship). Upon the death of his wife, Roy Complain, member of a primitive tribe of hunter-gatherers who live in a territory surrounded by jungle-like “ponics” (plant growth) known only as “Quarters,” joins another tribe’s expedition into the heart of darkness… in order to discover more about the world in which they live. This is an apophenic adventure — the protagonists of which seek meaning. Why is their world made of plastic and steel? What lies beyond the jungle? What’s the deal with the intelligent rats? The expedition’s leader, a priest named Marapper, has found ancient documents which seem to suggest that “Quarters,” and other territories, are… a gargantuan spaceship, an interstellar ark, headed from and to unknown destinations, on which two dozen generations have already lived. Marker’s plan is to find the ship’s control room, and to divert the ship to the nearest habitable planet. What lies ahead — in the ship’s control center? Fun fact: This was Brian Aldiss’s first novel — and it reflects his view that entropy will always derail grand human projects.

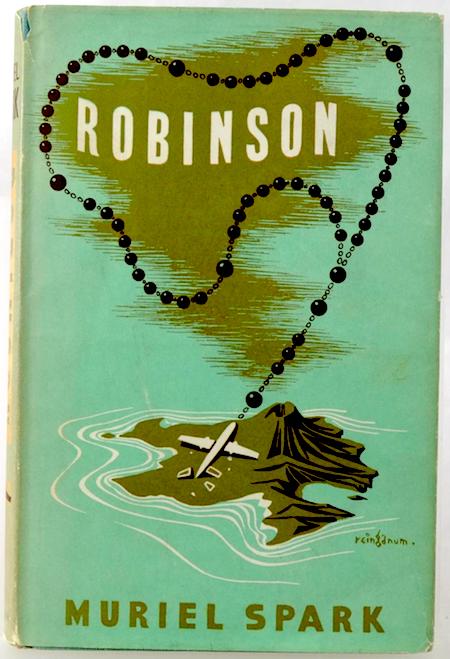

- Muriel Spark‘s apophenic Robinsonade Robinson. When a plane en route to the Azores crashes on a tropical island, a hermit who calls himself “Robinson” grudgingly cares for its three survivors. Except for his naive young ward, the Friday- (or Caliban-)like Miguel, and a cat, Robinson is the sole inhabitant of the remote atoll; in fact, he owns it. The first half of the novel explores the characters of the castaways: January Marlow, an opinionated journalist whose journal we’re reading; Wells, publisher of an occult magazine and purveyor of lucky charms; and Jimmie Waterford, who turns out to have been looking for Robinson. The island is a perplexing dreamscape, full of strange sounds and sights; its inhabitants misunderstand each other; items are stolen; and January and Robinson argue about Catholicism; she is a recent convert, he has left the church. Then, Robinson disappears — leaving behind blood-stained clothes. Has he been murdered? If so, which of the remaining four characters might have wanted him dead? There’s a search; mounting tension; January speculates about who might have done it, and why; and, near the end, there’s a headlong flight from danger. The reader is left to ask: Whose story is this? Fun facts: Spark’s second novel is a sardonic inversion of, and meta-commentary on castaway tales such as The Tempest, The Island of Doctor Moreau, Lord of the Flies, and of course, Robinson Crusoe.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.