The Clockwork Man (Intro)

By:

August 2, 2018

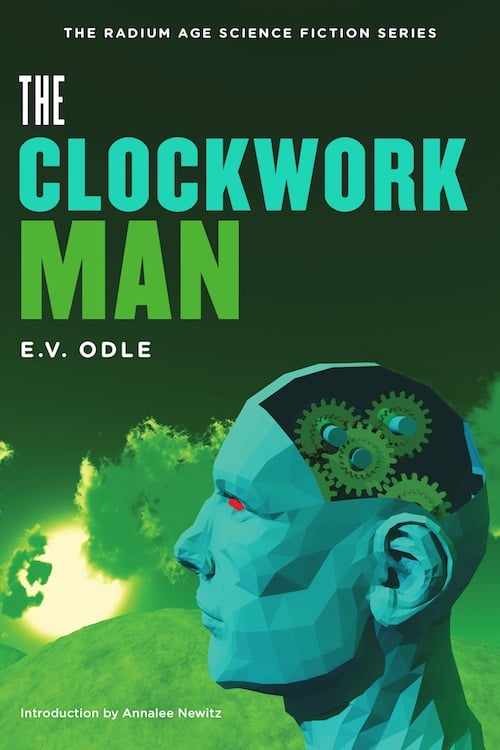

In 2013 HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued E.V. Odle’s Radium Age sci-fi novel The Clockwork Man (1923) in paperback form. Annalee Newitz, at that time editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9 and author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013), and since then author of the science fiction novel Autonomous (2017) — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

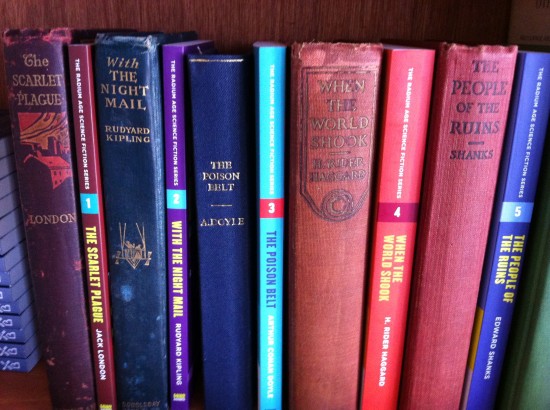

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

If you don’t stop making war on each other, one day women will team up with benevolent, naked aliens and implant you with a clock that controls your behavior and sends you into a timeless multiverse. Oh and also? That timeless multiverse will be full of hat and wig stores.

This is the warning expressed in E.V. Odle’s 1923 novel The Clockwork Man, and the goofiness is intentional. One of Odle’s preoccupations in this story is the way truly futuristic ideas strike us as hilarious. As his witty but conservative character Allingham observes, humanity’s most pernicious defense against change is an ability to turn anything into a joke. When our characters first observe the Clockwork man, a peculiar cyborg from thousands of years in the future, he’s gone glitchy. He’s spouting odd phrases and stumbling awkwardly through a small town cricket match. Their first impulse is to laugh at him, and this is perhaps more chilling than their subsequent excitement and terror as they realize what he really is.

The Clockwork Man is one of the first cyborg novels ever written, and undoubtedly Odle was anticipating his audience’s snorts of derision at his bizarre creation: a human man whose skull is implanted with an elaborate clock mechanism which he comically covers with a hat and wig. But he was not the only writer obsessed with synthetic humans in 1923. Karel Čapek’s classic robot uprising play R.U.R. came out that year as well. The play introduced the word “robot” and stole the spotlight from Odle’s weirder tale.

Unlike the synthetic workers of R.U.R., the Clockwork man was born a human. But his nervous system, brain, and body have been enhanced with technology: he does not die, he is exceptionally strong, he can sense physical phenomena beyond the capacity of the human mind, and his physical attributes can be changed with the poke of a knob. Ordinarily, he explains, he exists in a multiverse where all his desires are satisfied simply through a kind of “conjuring” of whatever he wants. He’s especially stumped by the way humans are always putting finite objects into finite places. In the Clockwork man’s distant future, all objects can be anywhere, anytime.

The Clockwork man, in other words, has returned from beyond what today’s science fiction writers would call the Singularity — and he finds our limited world bewildering, though ultimately seductive.

It’s striking how many obsessions of contemporary science fiction show up in Odle’s novel. Using this mechanized man, Odle is able to muse on what might happen to humanity after what Singulatarians call “the intelligence explosion” when the human mind is enhanced beyond all recognition by merging with computers. The Clockwork man seems to come from a virtual world of infinite plenitude, much the way uploaded people do in the work of Iain M. Banks and Ken MacLeod.

Embedded in the figure of the cyborg, from his very first appearance in literature, is the idea of a Singularity which involves virtual worlds and brain implants. There’s even a kind of dawning knowledge of the “uncanny valley,” a late twentieth century theory that describes the feeling of revulsion and hilarity inspired by robots who look almost human, but not quite. Something about the para-humanity of the Clockwork man’s appearance makes people burst into laughter, or throw up — or bite their lips to prevent both.

As the novel unfolds, we learn that the Clockwork man has fallen back into linear time, thousands of years in his past, because his mechanism is broken. He’s stuck in 1923, in our monoverse, and he bears a garbled message from the future to three men whose lives he changes forever. These men, the middle-aged doctor Allingham, the recent Cambridge grad Gregg, and the young dreamer Arthur, respond very differently to the prospect of humanity’s mechanized future. And those responses hinge in part on their view of women.

Odle was writing at a time when women’s rights were an enormously important issue of the day, and female political power loomed as a futuristic threat and promise. Odle lived for many years in the Bloomsbury district of London with his wife Rose, and these issues would have been fused with the dominant literary figures of his generation. Not only was he living in the same neighborhood as writers like Virginia Woolf, but Odle’s older brother Alan was married to the famous bohemian literary author Dorothy Richardson. She is often credited with writing the first stream-of-consciousness novel in English (Pointed Roofs), and she dated H.G. Wells for many years before settling down with Alan Odle. In Rose Odle’s autobiography, Salt of Our Youth, she recalls that Richardson’s mentor J.D. Beresford helped Odle publish his first novel, The History of Alfred Rudd, the year before The Clockwork Man came out. (Beresford was the author of classic SF novels The Hampdenshire Wonder and Goslings.) Through his family associations, Odle would have been exposed to a world where women dominated the artistic scene.

It’s no surprise, then, that the stuffy doctor Allingham’s horror at the Clockwork man is paralleled only by his horror at the radical ideas about woman’s equality espoused by his fiancée Lillian. Cyborgs and women represent the future, and not just metaphorically. In a fascinating passage toward the end of the novel, Odle explores how Allingham’s conflicts with Lillian, if left unresolved, could result in a gender apocalypse.

As the novel reaches its climax, Lillian is considering calling the marriage off because she believes Allingham wants her to be a traditional wife who spends all her time doing housework and managing his affairs. She’s also dismayed by his habit of turning everything into a joke — an issue that ties into Odle’s larger point about humor as a defense against the future. Allingham reluctantly admits that she has a legitimate point of view, but their conflict is never quite resolved.

While Allingham and Lillian discuss their relationship, the Clockwork man figures out how to fix his broken mechanism. But he remains in our timeline long enough to have a strange conversation with the young Arthur and his beloved Rose (no doubt named for Odle’s wife, to whom he also dedicated the novel). Arthur has been struggling to make enough money to marry Rose, who doesn’t care a fig for conventions that say men should be breadwinners. She’s encouraging him to pursue his dream, which is to become a writer. Unlike Allingham, who can barely see his way forward into a future where women are his equals, Arthur is already inhabiting that future. He’s contemplating shedding the conventional male breadwinner role, and his future wife is encouraging it.

When the Clockwork man wanders down a country road and sees Arthur and Rose embracing and whispering about their plans, he decides to tell them why the future is full of men like himself. Their love has reminded him that his incredible superpowers come at the expense of emotions. With tears running down his face, he explains that the Clockwork men are the creation of “makers,” creatures who came to Earth “after the last wars.” It’s unclear whether these makers are aliens or advanced humans, but we know they don’t wear clothes and are “very clever, and very mild and gentle.” The Clockwork man also describes them as “real,” unlike himself.

He tells the open-mouthed Arthur and Rose that men of the future became so obsessed with war that the makers allied with women — also “real” — and banished men from their world. Men’s destructiveness, and their inability to perceive the realness of women, were their downfall. This is Allingham and Lillian’s conflict over gender roles writ large. The cyborg explains that men left the makers no choice but to “shut us up in the clocks,” and give them “the world we wanted,” absent of emotion but filled with infinite power and resources.

Here it becomes clear that the Clockwork man lives mostly in a virtual world, “the clock,” rather than the “real” world that is apparently still inhabited by women and makers in the far future. He’s an analog version of an upload, and his world of plenitude is also a prison. In this scenario we see echoes of early feminist science fiction like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 Herland, as well as the anxieties expressed by pundits like Henry Adams, who noted in his 1905 book The Education of Henry Adams that women would achieve equality in part by “marrying machinery.”

While it’s temping to say that The Clockwork Man’s narrative arc is informed primarily by feminism, as Odle’s frequent references to Einsteinian physics and evolutionary theory attest, it is also strongly influenced by the ways science was transforming our understanding of the world. It was also written under the shadow of World War I. Odle worked as the foreman at a munitions factory during the war, and his vision of a battle-mangled future was surely spawned by his experience of those years.

Perhaps more importantly, however, this novel is the product of a time and place where pulp fiction and literature overlapped. In 1926, three years after publishing The Clockwork Man, Odle became the first editor of popular British literary magazine The Argosy (not to be confused with the American pulp magazine of the same name), which specialized in reprinting short stories by luminaries like Joseph Conrad, H.G. Wells and Oscar Wilde.

When Odle began his fourteen-year tenure as editor of The Argosy, the magazine was devoted to literature but it was published in pulp-sized format. So it would have looked like Weird Tales – or the American Argosy – but it contained short stories by literary authors. As pulp magazine historian Mike Ashley told me, it was also one of Britain’s best-selling magazines, despite being reprint. Odle’s great genius was an uncanny ability to bring little-known stories to public attention. According to Ashley, Odle and his editorial team “scoured [Argosy parent company] Cassell’s magazine archive and other sources to find unusual and rewarding stories, usually by well-known writers, but where the story itself was little known.” The magazine Odle created was so successful that it continued into the 1970s, several decades after his early death in 1942.

To understand the narrative construction of The Clockwork Man, we must view it as a book on the boundary between pulp and literature. Its ending isn’t merely an “as you know, Bob” infodump; it’s also part of an ambiguous web of possibilities stemming from the characters’ variations in perspective.

While Allingham views the Clockwork man’s future as frighteningly unimaginable, Gregg realizes that it’s actually not very different from the contemporary world. When the two men come across the cyborg’s lost hat, they find a tag inside from Dunn & Co., a popular London men’s clothing manufacturer in 1923 — which, in the Clockwork man’s future, has been a going concern for 2,000 years (the real-life Dunn & Co. closed its doors in the 1970s). Gregg realizes that immortal life inside the clock has allowed men to perpetuate ancient institutions long after they would have naturally perished in the real world. There’s an inherent conservatism in the Singularity, which allows men to transcend time only to foreclose the possibility of future changes.

Then there is the novel’s key revelation, which is that the Clockwork man is just one possible future for humanity. We won’t all be imprisoned/liberated by the clock. Many humans exist in the real world of makers and women. Like a pulp fiction writer, Odle gives us a grotesque future jammed with aliens, robots and Einsteinian wonders; but like a literary Modernist, he refuses to define that as the only pathway to tomorrow. There are many futures, many perspectives, and many possibilities. Allingham and Lillian’s relationship hints at the conflict that forces women to banish men to the clock. Arthur and Rose’s romance figures a “gentle” future of makers and women living together in naked harmony. And the Clockwork man’s hat gooses us into remembering that even a shockingly futuristic vision may be, at its core, a fundamentally reactionary enterprise.

Thanks to Jess Nevins for research aid!

MARCH 2013 — JULY 2013

Rumors that “E.V. Odle” was a pen name for Virginia Woolf are amusing, but unfounded. Edwin Vincent Odle (1890–1942) was a playwright, critic, and short-story author who lived in Bloomsbury, London during the 1910s; his brother, Alan, was a well-known illustrator and eccentric. From 1925–35, he was editor of the British short-story magazine The Argosy.

“Edwin Vincent Odle’s ominous, droll, and unforgettable The Clockwork Man is a missing link between Lewis Carroll and John Sladek or Philip K. Dick,” says Jonathan Lethem in a 2013 blurb for HiLoBooks. “Considered with them, it suggests an alternate lineage for SF, springing as much from G.K. Chesterton’s sensibility as from H.G. Wells’s.”

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man,” writes Brian Stableford in Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.”

“Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s,” agrees the sci-fi reference book Anatomy of Wonder.

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.