The People of the Ruins (Intro)

By:

May 3, 2018

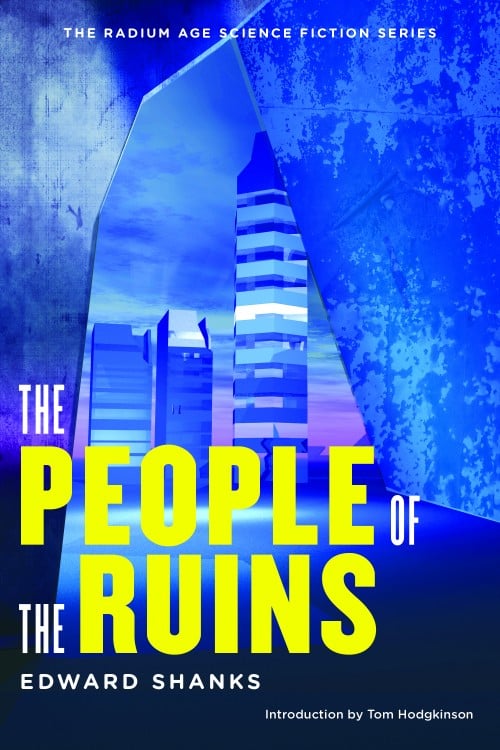

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued Edward Shanks’s 1920 Radium Age sci-fi novel The People of the Ruins in paperback form. Tom Hodgkinson, editor of the British journal The Idler, and author of How To Be Idle and Brave Old World, among other titles, provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

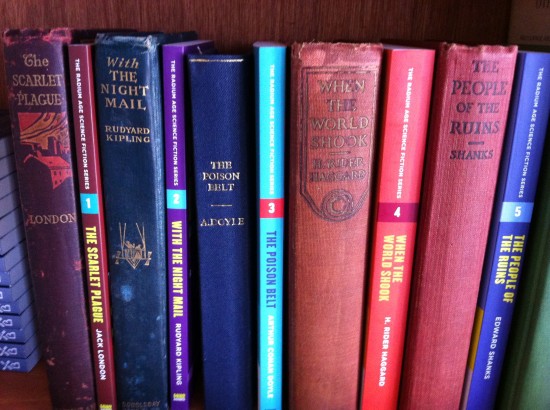

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

It is 1924 and London is in the grip of a proletarian uprising. Our hero, an earnest young physics lecturer named Jeremy Tuft, gets called a “dirty boorjwar” by a revolutionary truck-driver as he walks down the riot-torn streets of Whitechapel in East London. In his scientist friend’s flat, a bizarre experiment is going on, involving a new kind of ray with untested properties. A bomb hits the house and Jeremy gets zapped by the ray. He falls into a deep sleep and wakes up in 2074 to find that society has reverted to a sort of pre-industrial state. The leader of post-apocalyptic England refers to the revolution of 1924 as “The Troubles” and looks back to the pre-revolutionary time as a golden age of knowledge and sophistication.

Such is the premise of The People of the Ruins: A Story of the English Revolution and After by poet and journalist Edward Shanks, written in 1920, just two years after the end of the horrifying Great War. Style-wise, it is fair to say that Shanks lacks the light touch. The reader needs to do a lot of wading. Having said all that, it is a very good and a very interesting novel, and the patient reader will be well rewarded.

The People of the Ruins has a certain gloomy charm to it. Tuft is delighted with some aspects of the ruined society. The noble families seem more interested in gardens than buildings. “Jeremy walked in a great shrubbery where Charing Cross Road had been and in a rose garden on the deep-buried foundations of Scotland Yard.” That’s an appealing image, almost Blakeian. Central government is very small, and the provinces govern themselves, which should cheer the anti-statist libertarians amongst us.

It’s not all rosy. Some of the inhabitants live in squalor: “Jeremy saw in the fields bowed laborious figures wrapped in rags which forbade him to say whether they were men or women, and troops of dirty, half-naked children.” Despite all this a new beauty opens up in London, and Jeremy sees in it a sort of Epicurean paradise: “You are happier than we were,” he says to his pal, “though you are poorer. Your air is clean, you have room, you live at peace, you have time to live… I can remember how delicious it was to lie down in a field off the road, to let the business all go, not to care where one got to or when. It was this peacefulness we should have been aiming at all the time, only we never knew…”

He goes on to express anti-consumerist and anti-work sentiments that chime harmoniously with the writer of this introduction: “We wretched ants piled up more stuff than we could use, and though the mad people of the Troubles wasted it, yet the ruins are enough for this people to live in for centuries. And aren’t they more sensible than we were? Why shouldn’t humanity retire from business on its savings? If only it had done it before it got that nervous breakdown from overwork!”

Just as today, the anxiety culture and alienation were pressing issues in the Twenties, particularly to thoughtful young men who had seen close up the slaughter of the First World War. And like today’s Thoreaus, Jeremy approves of the lack of machines. Somehow without them there is more time for living rather than less. “The trains were few and uncertain, and, from the universal decay of mechanical knowledge, were bound in time to cease all together; but England, so far as Jeremy could see, would get on very well without any trains at all. There was no telephone; but that was in many ways a blessing. There was no electric light… But it was certainly possible to regard candles and lamps as more beautiful. The streets were dark at night and not over-safe; but no man went out unarmed or alone after sunset, and actual violence was rare.”

Another appealing feature of the new world, to those of us who are saddened by the rise of the megalopolis, is a sort of deurbanization: “He gathered that [the countryside] was richer and more prosperous than he had known it, and that the small country town had come again into its own.” The social life, though, seems distinctly dismal: at a party Jeremy attends, aloofness, small talk and indifference seem to be the order of the day. Manners appear to have reverted to a courtly formality. No one seems to have any fun: where is the maypole dancing and music? Jeremy finds the clothing garish and gaudy, and compares the women’s dresses to “a wallpaper of the 19th century”, probably a dig at the medievalism of William Morris.

The reader at this point starts to wonder whether or not he would prefer this new world to our own. I suppose it is a strength of the book that the answer is not clear. One man who does not share Jeremy’s enthusiasm for this world is its leader, a sinister figure called The Speaker. While Jeremy finds much to commend, the Speaker regrets its loss of technical knowledge. In particular he wants guns, and sets Jeremy to work in manufacturing cannons for a forthcoming showdown with enemies from the North. Demonstrating a lack of awareness of political correctness, he hints that if Jeremy is successful in this project he’ll get to shag his daughter, the feisty Lady Eva: “You shall have your reward. I have no son and I have a daughter.”

Jeremy is profoundly uncertain about the wisdom of getting back with the military-industrial programme. “He was sometimes far from sure that a regeneration which began by the manufacture of heavy artillery was likely to be a process of which he could wholly approve. He found this age sufficiently agreeable not to wish to change it. It was true that innumerable conveniences had gone. But on the other hand most of the people seemed to be reasonably contented, and no one was ever in a hurry.”

Despite such misgivings, he finds himself the reluctant leader of a raggle-taggle band of soldiers, and there is a terrific showdown with the men from Yorkshire. Well, without wanting to spoil the plot, Jeremy Tuft does get the girl, hooray! There is a moment of joy amid the darkness. And we are treated to a fine image of soldiers bedecked in flora: “The troops marched off down Oxford Street and along the winding valley-road, covered again with flowers, which they stuck in their hats or in the muzzles of their rifles.” But you couldn’t say that the book has a happy ending.

As dystopian fantasies go, Shanks was later outshone by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World and George Orwell in 1984. And Shanks’s premise seems lifted from News From Nowhere by William Morris, in which a young hero returns home gloomily from a political meeting in the late 19th century and wakes to find himself transported into a future utopia where money has been abolished and a craft economy thrives. However, we must credit Shanks for creating a ground-breaking and very widely read book that may well have influenced the later experiments of Huxley and Orwell. And it could be argued that his gloom was a riposte to the perhaps naive optimism of Morris’s fantasy.

So, while not a masterpiece, The People of the Ruins can be read with pleasure both as a curiosity item and for its own sake. Philosophically it occupies strange ground. It has none of the techno-utopianism of H.G. Wells, but then none of the revolutionary zeal of William Morris either. The socialists of the time would have found it too pessimistic with its vision of an apathetic state structure. But it has no ‘good old days’ nostalgia either. It is bleak and uninspiring, and its only conclusion as far as society goes appears to be: you can’t win!

Most readers though would find a lot to agree with here. Like Shanks and like Morris, I think that the modern world leaves a lot to be desired, because of the state of anxiety it produces in many of us, the ennui, the sense of being perpetually unsatisfied. In chasing a technological utopia something has been lost. We don’t quite feel in control of our own world. We work for the machine and not for ourselves. A part of us longs to connect with nature and with our own creativity. But despite these difficulties, I would remain optimistic, because it is not impossible to create little patches of paradise amid the hurly-burly: a shed, a study, a back yard, a contemplative space.

A measure of freedom can certainly be found in everyday life by simply turning the clock back to the Middle Ages, when life was less comfortable, to be sure, but when we were not separated from the means of production by the factory system. G.K. Chesterton, the great English essayist of the early 20th century, wrote: “We must go back to freedom or forward to slavery,” and this paradox is well worth exploring.

MAY — SEPTEMBER 2012

Edward Shanks was an English author, poet, critic, and journalist. He was editor of the literary journal Granta just before serving in World War I; he is perhaps best remembered today as a war poet. The People of the Ruins is his only science fiction novel.

“The first of the many British postwar novels that foresee Britain returned to barbarism by the ravages of war.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed. (1976)

“One of the most widely read scientific romances of the post-war years.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain 1890-1950 (1985)

“After World War I British futuristic fiction was dominated by the idea that a new war could and probably would obliterate civilization…. Utopian speculation was not entirely stifled but undermined and opposed by cynicism.” — The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English, Ian Ousby, ed. (1996)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.