10 Best Adventures of 1933

By:

April 28, 2018

Eighty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Twenties (1924–1933) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

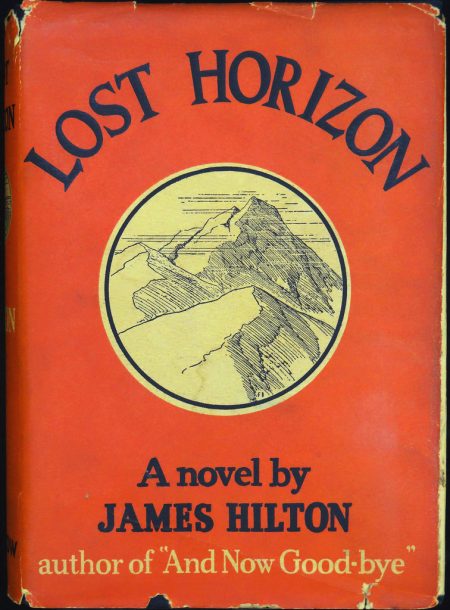

- James Hilton’s fantasy adventure Lost Horizon. When the European and American residents of Baskul are marooned during a Persian revolution, a small group — including Hugh Conway, a veteran member of the British diplomatic service (and an ironist whose worldview is perhaps beginning to turn cynical) — flees in a plane that is hijacked. Crash-landing near a remote Tibetan valley, they’re rescued and taken to the nearby lamasery of Shangri-La… which they’re not permitted to leave! Mallinson, Conway’s young deputy, is eager to depart… but the other travelers find themselves drawn, for various reasons, to Shangri-La’s peaceful, contemplative life. Mallinson falls in love with a young Manchu woman, Lo-Tsen, whom he wants to take with him when he escapes; Conway, meanwhile, gets to know the High Lama, from whom he learns the amazing secret of Shangri-La. When Mallinson organizes an escape plan, will Conway go with him? Or will he remain in the valley, and take over as High Lama? Fun facts: The novel was a huge popular success, at the time. When Simon & Schuster produced the first mass-market, pocket-sized paperback books in America in 1939, Lost Horizon was Pocket Books #1. Frank Capra directed the 1937 film adaptation, starring Ronald Colman; it seems likely that the movie influenced Steve Ditko’s Dr. Strange.

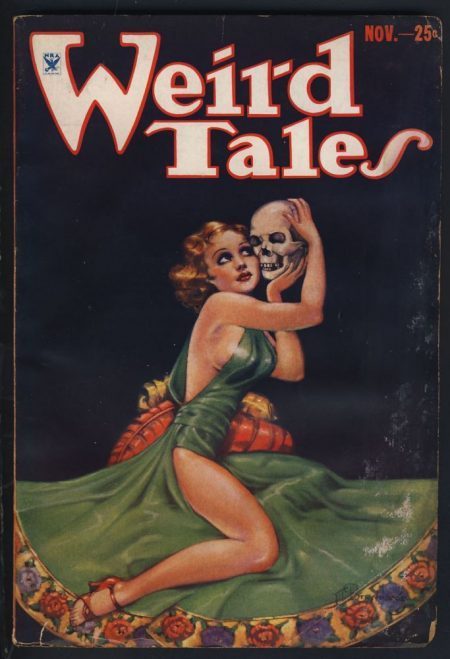

- C.L. Moore’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Northwest Smith (1933-on; collected in book form, 1953). In the far future, humankind has colonized the solar system. The ruthless, cynical spaceship pilot and smuggler Northwest Smith roams from planet to planet, looking to make a quick buck. In “Shambleau” (November 1933), for example, Smith rescues a strange, beautiful girl from a Martian mob; in “Black Thirst” (April 1934), he ventures into a forbidden Venusian fortress. And in “Dust of Gods” (August 1934), Smith and his Venusian comrade, the Wookiee-like Yarol, take a job searching for the physical remnants of a dead god. In many of these yarns, all of which appeared in Weird Tales — during that magazine’s H.P. Lovecraft/Robert E. Howard/Clark Ashton Smith era — Smith undergoes outré psychological/spiritual trials, which take place in extra-dimensional or dream-like contexts. Fun facts: Catherine Lucille Moore was among the first women to write pulp science fiction and fantasy. She and her first husband, Henry Kuttner, were prolific co-authors.

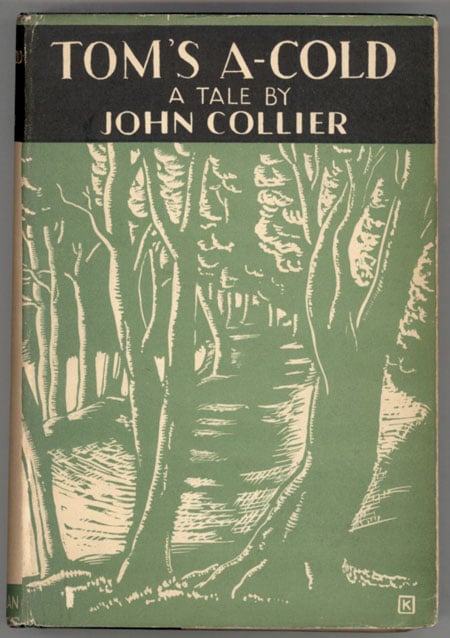

- John Collier’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Tom’s A-Cold (US title: Full Circle). Though best remembered for his mordant, fantastical short stories, many of which appeared in The New Yorker, John Collier also wrote two Radium Age science fiction novels. Tom’s A-Cold is set in 1995, at which point England (along with the rest of the world, presumably) has reverted to a medieval-style social order and way of life. This is, in some sense, a “cozy catastrophe” — Collier describes the reborn natural world movingly. (What happened to civilization? Greed, laziness, and bureaucracy.) Harry, who has grown up in a valley in Hampshire, under the egotistic rule of the Chief, is being groomed by his grandfather, one of the few elders who remembers modern civilization, to take over the tribe. Over the course of a summer and fall, during and after a raid on a nearby village, to capture women, Harry does become Chief — but at the cost of everything he cares about. Fun facts: Collier was a fixture on the English literary scene during the 1920s and ’30s. In Hollywood, years later, he helped develop TV shows like Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

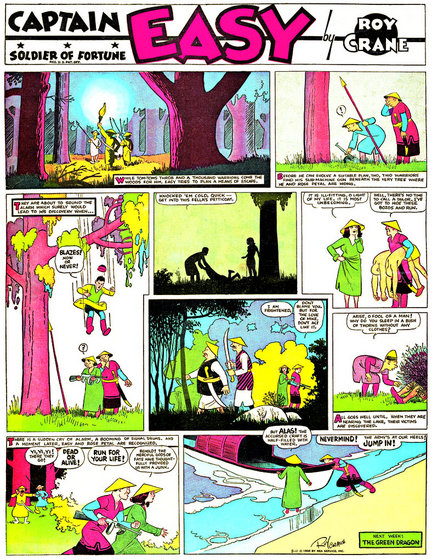

- Roy Crane’s Captain Easy Sunday comic strip (1933–1937). Crane’s long-running Wash Tubbs (1924–1988) has been called the first true action/adventure comic strip. However, the diminutive, girl-crazy Tubbs was a comical character, and the strip — like Kahle’s Hairbreadth Harry and Wheelan’s Minute Movies befotre it — was influenced by silent-movie melodramas and vaudeville. In 1928, the debut of Foster’s Tarzan and Knowlan and Calkins’s Buck Rogers launched the era of the more dramatic, authentic adventure strip; in 1929, Crane introduced the tough Southerner Captain Easy as Tubbs’s sidekick. Though drawn in a “cartoony” way, the strip was an exciting one… and in 1933 Easy got his own Sunday page, Captain Easy, Soldier of Fortune. Crane exploited the possibilities of a full newspaper page to their fullest: As R.C. Harvey notes, “When Crane drew Easy at the brink of a cliff, he gave depth to the scene by depicting it in a vertical panel that is two- or three-tiers tall. When Easy leads a cavalry charge or paddles a canoe down a lazy river, the panel is as wide as the page, giving panoramic sweep to the scene depicted.” Alas, in 1937, Crane’s syndicate began requiring Sunday strips to be modular. Crane quit the Sunday strip, and in 1943 quit Captain Easy altogether. Fun facts: Crane has been credited with pioneering the use of onomatopoeic sound effects — BAM, POW, WHAM — in comic strips. Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy were featured in Big Little Books during the 1930s; and in Dell comic books in the ’30s and ’40s. Superman co-creator Joe Shuster cited Crane as an influence. Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates (1934–on): second-time-as-tragedy?

- Dorothy L. Sayers‘s Lord Peter Wimsey crime adventure Murder Must Advertise. Some Sayers fans consider this the best Wimsey novel; I don’t agree — there isn’t enough Harriet Vane — but it’s still pretty great. After the suspicious death of copywriter Victor Dean, in the offices of Pym’s Publicity, Wimsey goes undercover in the agency… as copywriter and louche man-about-town Death (“Deeth”) Bredon. Sayers worked for years in a London ad agency, and her depiction of Pym’s is less satire than a semi-affectionate, semi-acidulous send-up of the daily process via which consumers are hoodwinked. In fact, the book has been described as a novel about an ad firm that just happens to concern a murder… though, as the plot thickens, we discover that there’s a more sinister game afoot: sex, drugs, and blackmail among London’s postwar Bright Young People! And more murders, too not to mention an epic intramural cricket match between Pym’s and a soft-drink company’s team. Fun facts: R.A. Bevan, a significant figure in 1920s–1930s British communications and advertising (think: Guinness, Bovril, Johnnie Walker, Colman’s Mustard), was the the inspiration for the novel’s Mr Ingleby character.

- Dennis Wheatley’s The Forbidden Territory. Rex Van Ryn, an American adventurer, has journeyed into the Soviet Union in search of Prince Shulimoff’s treasure — jewels which were hidden during the Communist takeover. Having wandered into “forbidden territory” which is off-limits to foreigner, he is imprisoned by the Soviets and sends a coded letter to his friend, the Duke de Richleau. Richleau recruits Simon Aron (a Jewish financier) and Richard Eaton (a British pilot) to accompany him on a rescue mission. The men split up, so this is three adventures in one, along with some romance: Aron falls in love with a Communist actress, and Eaton with Shulimoff’s illegitimate daughter. The depiction of Soviet Russia — shortages, secret police — is an unflattering one, though Hergé’s Tintin au pays des Soviets (1929–1930) is more overtly anticommunist. Fun facts: This is Wheatley’s first published novel. Wheatley’s Gregory Sallust thrillers are often cited as an influence on Fleming’s James Bond books; and he wrote several occult adventurers starring Duke de Richleau’s friends. Though a bestselling author in England, he never achieved much popularity in America.

- Hervey Allen’s historical adventure Anthony Adverse. This is a massive door-stopper, three books in one, and tedious in places (unless you’re really interested in early 19th century mercantile activity). But don’t be daunted — it’s also an eventful adventure that takes us from Napoleonic-era Italy, France, and Spain to Africa, the West Indies, Mexico, and North America. “Anthony Adverse” is a foundling — the son of a Scottish woman married to an evil Spanish nobleman and her lover, a French nobleman — who is apprenticed to a British merchant in Italy. He travels the world, making and losing fortunes — slave trading in Africa, for example, or running a plantation in New Orleans — before undergoing a religious conversion, renouncing material possessions in general and the owning of slaves in particular, and ending up in a New Mexico (then still Spanish territory) mission. There is plenty of romance and swashbuckling action along the way, and we meet several famous figures of the era, including Napoleon himself. Fun facts: Anthony Adverse was hugely popular, at the time, until it was eclipsed by another massive historical adventure: Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. In an attempt to prove that Warner Brothers could handle sweeping historical epics like MGM and Paramount, the book was adapted by Mervyn LeRoy as a (somewhat disappointing) 1936 costume drama starring Fredric March and Olivia de Havilland.

- Dashiell Hammett‘s crime adventure The Thin Man (serialized, 1933; in book form, 1934). Nick Charles, having married Nora, a wealthy Californian socialite, is no longer interested in pursuing his former career as a private detective. He and Nora are enjoying themselves, over Christmas vacation, in New York’s speakeasies when they’re drawn into the investigation of a murder: the mistress of scientist Clyde Wynant, one of Nick’s former clients and the titular thin man. Nora’s fascination with her husband’s previous life — including his colorful associates — trumps Nick’s reluctance. There are many suspects: Wynant’s ex-wife, Mimi, and her new husband; his alluring daughter and morbid son; his mistress’s gangster boyfriend…. Yes, the movies are funnier, but the book’s noir elements make it a compelling read, and it’s funny too. Fun facts: Originally published in the December 1933 issue of Redbook; the characters Nick and Nora were inspired by Hammett and his on-again and off-again lover Lillian Hellman. The novel, Hammett’s last, became the basis for a six-part screwball comedy film series starring William Powell and Myrna Loy.

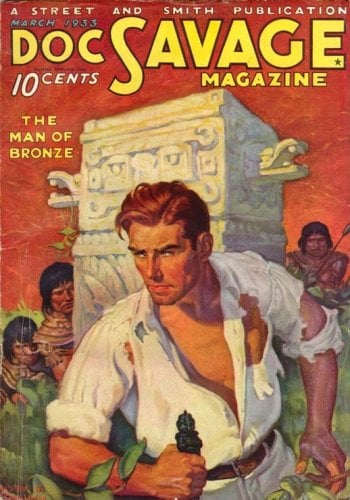

- Lester Dent’s Doc Savage (1933-on). In a good example of the first-time-as-comedy-second-time-as-tragedy trope, the “Doc Savage” character — Clark Savage Jr., a nearly superhuman surgeon, scientist, adventurer, inventor, explorer, and researcher — is an earnest rip-off of Henry Stone, protagonist of Philip Wylie’s sardonic superman novel The Savage Gentleman (1932). An expert at disguise, not to mention hand-to-hand combat, Savage’s only goal in life is to right wrongs and punish evildoers. He is accompanied, in many of his adventures, by the brilliant chemist “Monk” Mayfair, dapper attorney (and Brigadier General) “Ham” Brooks, construction engineer and strongman “Renny” Renwick, electrical engineer “Long Tom” Roberts, and be-monocled archaeologist Johnny Littlejohn. Their HQ is on the 86th floor of a New York skyscraper (implicitly the Empire State Building); and Savage also has a Fortress of Solitude in the Arctic. Here we see Golden Age themes and memes emerging from the Radium Age. Fun fact: Of the 181 Doc Savage novels published by Street and Smith, 179 were credited to “Kenneth Robeson”; in fact, all but 20 of these novels were written by Lester Dent. There was a 1940s comic book, and a radio show based on the comic; Bantam Books began reprinting the novels in 1964, introducing the character to a new generation of fans; and there was a campy 1975 movie, the last film completed by George Pal.

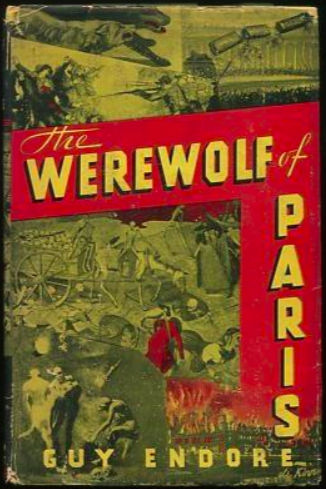

- Guy Endore’s horror/historical adventure The Werewolf of Paris. Often described as “the Dracula of werewolf stories,” Endore’s story concerns Bertrand Caillet, a French “wild boy” whose nightmares are replete with sadistic sex and lupine transformation… are the mutilated corpses that seem to follow him everywhere evidence that he is a monster? Caillet wanders around France, on a murder and terror spree, seeking to tame the raging beast within (with whom he cannot communicate). Eventually, he ends up in Paris during its 1870–1871 siege by Prussian forces and the ill-fated Paris Commune; the resulting mayhem allows Caillet to satisfy his desires without fear of discovery; he also begins to feed upon the blood of his willing lover — the beautiful and depraved Sophie de Blumenberg. Though not nearly as explicit as today’s horror fiction, The Werewolf of Paris was, for its time, stunning in its frank treatment of sex and violence. The novel’s Gothic-esque frame story is narrated by Caillet’s step-uncle, who sets out to hunt down and destroy the werewolf… while speculating that humankind is the true evil monster. Fun fact: A #1 New York Times bestseller upon publication. Terence Fisher’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), starring Oliver Reed, was the first film adaptation of the story.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.