When the World Shook (Intro)

By:

April 2, 2018

In 2012, HiLoBooks — HILOBROW’s book-publishing offshoot — reissued H. Rider Haggard’s Radium Age sci-fi novel When the World Shook (1919) in paperback form. James Parker — author of Turned On: A Biography of Henry Rollins and a contributing editor at The Atlantic — provided a new Introduction, which appears online for the first time now.

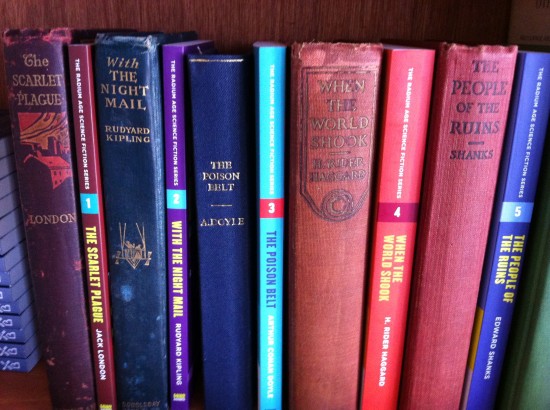

INTRODUCTION SERIES: Matthew Battles vs. Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Matthew De Abaitua vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Joshua Glenn vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | James Parker vs. H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Tom Hodgkinson vs. Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins | Erik Davis vs. William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | Astra Taylor vs. J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | Annalee Newitz vs. E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Gary Panter vs. Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Mark Kingwell vs. Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses | Bruce Sterling vs. Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (Afterword) | Gordon Dahlquist vs. Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (Afterword)

Boom and bang go the Zeppelin bombs over the fields of Norfolk, whump and crump, while in the cellar of the large house the distinguished author shelters distinguishedly with his family and staff. His days of conquest are over and his lungs hurt. But the world is shaking, shaking, and within himself he detects, yes, a quickening of the ancient juices…

Can we attribute the late-career energy-burst of When the World Shook, at least in part, to German high explosives? In 1916 Sir Henry Rider Haggard was sixty years old and feeling it. “My work, for the most part, lies behind me,” he wrote to his daughter Lilias, “rather poor stuff too — yet I will say this: I have worked.” Indeed he had, the old lion — worked, written, potboiled, romanced, travelled, campaigned, politicked and adventured more or less non-stop, loping like a schoolboy to the fringes of the Empire and the borders of nightmare. For a writer he had been almost unforgiveably active, even holding the hand of History when (to take but one example) he hoisted the Union Jack over Pretoria in 1877 and proclaimed thereby the British annexation of the Boer Republic of the Transvaal. By 1916, however, he was fallen into the sere, the yellow leaf. The author of King Solomon’s Mines could no longer command his wonted share of the market. He was bronchitic, he was melancholic.

But he had an Idea. Oro was alive in his mind: the reborn superman with world-destroying powers. In January he had written about Oro to Rudyard Kipling, prompting the younger man (a huge fan) to cries of epistolary joy: “Gad what an undefeated and joyous imagination you have!” In June he described for Lilias his vision of “the balance (or gyroscope) down in the bowels of the world on which the whole earth swings,” enjoining her please to not tell anybody else about it, because “it really is priceless.” In July he went to Canada, where a mountain and a glacier had been named after him – the Sir Rider Mountain and the Haggard Glacier. Then he returned to Norfolk in a state of exhaustion, was dosed with strychnine tonic by his doctor and nearly got himself squashed by the bombs above mentioned. Mid-March of the following year, When the World Shook was finished.

It’s a very strange book. I mean, aren’t they all, these Radium Age brainstorms? Their guilelessness in the realm of symbol, the gems of psychic materia embedded in their porridgey Edwardian prose: one can almost feel the Unconscious rising in pressure behind the text, rattling the crust, crowding towards its blowholes in Vienna, Paris, London… “Then bellowing like ten millions of bulls, at length far away there appeared something terrible. I can only describe its appearance as that of an attenuated mountain on fire. When it drew nearer I perceived that it was more like a ballet-dancer whirling round and round upon her toes, or rather all the ballet-dancers in the world rolled into one and then multiplied a million times in size. No, it was like a mushroom with two stalks, one above and one below, or a huge top with a point on which it spun, a swelling belly and another point above. On it came, dancing, swaying and spinning at a rate inconceivable…”

There it is, pirouetting between simile and simile, the gyroscope at the centre of the world. And highlighting this passage in Rider Haggard: The Great Storyteller, biographer D.S. Higgins has not the slightest hesitation in getting Freudian on his subject’s ass: “…erotic imagery — a herd of bulls, whirling dancers, a mushroom, a swelling belly — the whole appearing like a gigantic phallus with an enormous head moving along a subterranean channel.” In the wake of so engorged an apparition, avers Higgins, Oro’s subsequent failure to knock the planet off its axis “describes the experience of impotency, when the mental flames of desire are followed by a coldness of physical response so that the opportunity is lost.” One way to look at it, certainly. Another might be to note that within a few decades Western man would have managed to internalize Haggard’s wild world-spindle: by the time of Walker Percy’s The Second Coming (whose Will Barrett is an idle and sceptical fellow not a million miles from When the World Shook’s Humphrey Arbuthnot) the gyroscope has shrunk to fit inside the hero’s skull, less a symbol of sexual off-kilterness than a tiny dynamo of existential vertigo. “The gyroscope spinning in his head hurt his driving the Mercedes but helped his putting. All he had to do was settle over a putt, wait till the gyroscope steadied and the twisting stopped and zing, the ball flew straight for the cup like a missile locked on target.”

Then we have Haggard’s career-long thing for embalmed or encoffined beauties. Humphrey Arbuthnot begins the narrative nearly crippled by Seinfeldian heebie-jeebies: “I liked women, but at the same time they repelled me. My old fastidiousness came in; to my taste there was always something wrong with them.” But then the lovely Natalie breaches his barriers and steals his heart, and then the lovely Natalie dies, and Humphrey’s grief neurotically constellates around an image of eternal passion, passion beyond Time. And when, having sloshed across many seas, he finds the Glittering Lady lying in suspended animation in her glass sarcophagus — look out. “There she lay, her tall and delicate shape half-hidden in masses of rich-hued hair… From between the masses of this hair appeared a face which I can only call divine. There was every beauty which woman can boast, from the curving eyelashes of extraordinary length to the sweet and human mouth.” The sweet and human mouth — how odd! In pulseless stillness, in a state of death-in-life, in a reptile swoon, in a glamour, the beauty is contemplated with a curious frigidity.

But enough poking at the Haggard psyche. Let’s turn in closing to an example or two of his masterly control, the fruit of his muscular forebrain. When the World Shook, in addition to a splendidly panoramic astrally projected tour of the Western Front, contains an amount of surprising and well-achieved comedy — not a genre in which the great storyteller had previously distinguished himself. The humor turns mainly on Humphrey’s two dear friends and travelling companions, the excellently named double-act of Bastin and Bickley. Bastin is a priest, Bickley a surgeon and a devout materialist. Their clashes are constant but never bitter. Humphrey is operating his own little philosophical gyroscope here: round and round the argument spins, soul or no soul, God or no God, with Humphrey dizzily in the middle. Bastin, the man of faith, is magnificent in his crassness: “[His wife] was by nature a woman so insanely jealous that she actually managed to be suspicious of Bastin, whom she had captured in an unguarded moment when he was thinking of something else and who would as soon have thought of even looking at another woman as he would of worshipping Baal. As a matter of fact it took him months to know one female from another.” Bickley the empiricist is severe, waspish occasionally, but deeply fond of Bastin. For Humphrey their debate is a dead end: “It is impossible for a man to satisfy his soul, if he has anything of the sort about him which in the remotest degree answers to that description, with the husks of wealth, luxury and indolence, supplemented by occasional theological and other arguments between his friends.” Might it be his spiritual destiny to transcend the limited terms of Bastin vs Bickley — to ascend on winged feet above the either/or and surf the byways of space with the Glittering Lady? Might he take us with him? Please, Humphrey, please?

MARCH — AUGUST 2012

H. Rider Haggard wrote some of the most popular adventure novels of all time, including King Solomon’s Mines and its sequel Allan Quatermain (one of the inspirations for George Lucas and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones); and She and its sequel Ayesha.

“A really splendid romance, rich in color, fresh and gorgeous in its imaginative qualities and power, and needless to add, absorbingly interesting, is this wherein Rider Haggard tells us of what happened ‘When the World Shook.'” — The New York Times (1919)

“Speaking quite soberly and without exaggeration, this story of ‘When the World Shook’ is an amazing novel. Amazing in its imaginative quality, its romance, the splendor of its descriptions, doubly amazing when one remembers that it is the successor to a long series of colorful tales of adventure in savage or extraordinary lands… We frankly admit that, in our opinion at least, Rider Haggard has never conceived and placed before our eyes any pictures more thrilling or more impressive that are contained in this latest book.” — New York Evening Post (1919)

“Rider Haggard has again unbridled his splendid imagination. A thrilling, gigantic wonder tale.” — Pittsburgh Sun (1919)

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance. When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.” — Lydia Millet (2012 blurb for HiLoBooks)

Tony Leone designed the gorgeous cover of HiLoBooks’s edition of this book; and Michael Lewy provided the original cover illustration. (How much did New York Review Books like the look of our Radium Age series? So much that, with our encouragement, they hired Tony to design the paperback editions of their Children’s Collection.) Josh Glenn selected the books and proofed each page, to ensure that the text is faithful to the original.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s moniker for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This same era saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.”

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HILOBROW; and also, as of 2012, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. For more information, check out the HILOBOOKS HOMEPAGE.