10 Best Adventures of 1923

By:

March 22, 2018

Ninety-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Teens (1914–1923) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

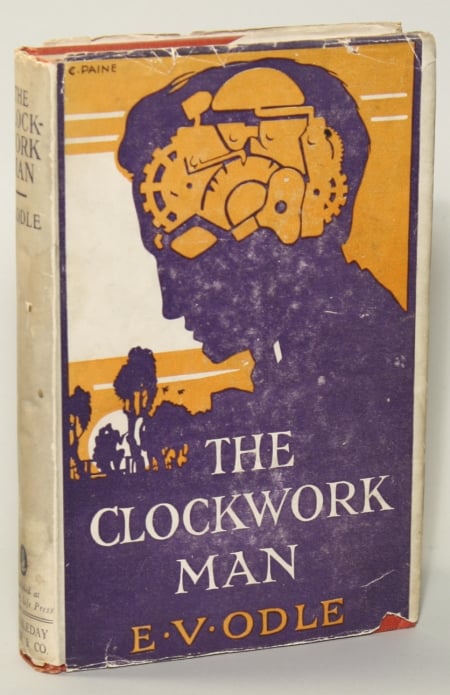

- E.V. Odle’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Clockwork Man (1923). Years from now, advanced beings known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these marvelous devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live perfectly regulated lives. However, if one of these devices should ever go awry, a “clockwork man” from the future might turn up in the 1920s, perhaps at a cricket match in a small English village. Considered the original cyborg novel, and perhaps the original singularity novel too. “Odle’s ominous, droll, and unforgettable The Clockwork Man is a missing link between Lewis Carroll and John Sladek or Philip K. Dick,” says Jonathan Lethem. “Considered with them, it suggests an alternate lineage for SF, springing as much from G.K. Chesterton’s sensibility as from H.G. Wells’s.” Fun facts: Reissued by HiLoBooks with an Introduction by Annalee Newitz. Rumors that “E.V. Odle” was a pen name for Virginia Woolf are amusing, but unfounded. Edwin Vincent Odle (1890–1942) was a writer who lived in Bloomsbury, London during the 1910s. From 1925–35, he was editor of the British short-story magazine The Argosy.

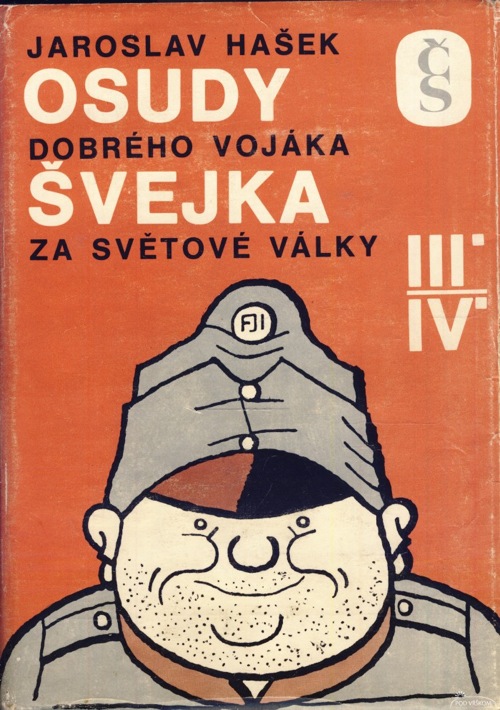

- Jaroslav Hašek’s comedic military adventure The Good Soldier Švejk (1921–1923). So popular was this unfinished, darkly humorous Czech story, considered the first antiwar novel, that in the 1920s–30s its protagonist became an avatar of lowbrow passive resistance. The cunning/bumbling Švejk, a dealer in stolen dogs, is among the first to sign up for military service after the assassination in Sarajevo that precipitates World War I. Wheeled into a Prague recruitment office by his landlady, Švejk is immediately accused of malingering because of his supposed rhematism; then, posted with his battalion to Southern Bohemia, preparatory to being sent to the front, Švejk misses every train there… and sets off on foot. No one knows quite what to do with him — is he an imbecile, a spy, a deserter, a traitor, a pacifist? Even as he arrives at the Russian front, he’s arrested by his own comrades… which perhaps was his plan all along? Along the way, like Scheherazade, Švejk tells stories — which he uses to distract, confuse, and craftily insult. Fun facts: Hašek was a journalist, anarchist, and dealer in stolen dogs who during WWI defected from the Czech legion and joined the Bolsheviks; he died in 1923, before finishing this novel. The term “Schweikist,” to use the English spelling of Švejk, was coined to mean, roughly: one who loudly proclaims his loyalty to the prevailing authority while simultaneously defying it in a thousand small ways.

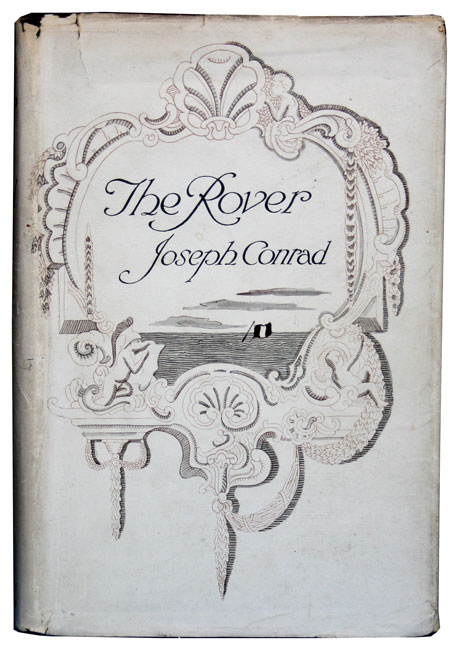

- Joseph Conrad’s historical/military adventure The Rover. Peyrol, an amoral pirate turned sailor in Napoleon’s navy, retires to a coastal farm in southern France with his ill-gotten gains; for fun, he repairs and rigs an old boat. The farm’s owner, the beautiful Arlette, has been half-crazed ever since the Revolution, when her parents were murdered and she herself participated in atrocities; Arlette’s husband — if they were ever married — is a bloodthirsty revolutionary, Scevola. This weird but quiet household is disturbed when an enigmatic French lieutenant, Réal, shows up. Arlette falls in love Réal; Scevola wants to murder him. Réal, meanwhile, wants Peyrol to participate in a half-baked plan to allow fake documents to be captured by the British corvette patrolling the coast — thus sending Lord Nelson off on a false trail. Peyrol could do something heroic for France, and kind for Arlette… but why should he? Fun facts: Conrad’s final novel. Like the character Nostromo in the novel of that title, Peyrol is based on a Corsican ex-pirate whom Conrad had known as a teenage sailor in the 1870s. Yes, there was a movie adaptation with Anthony Quinn.

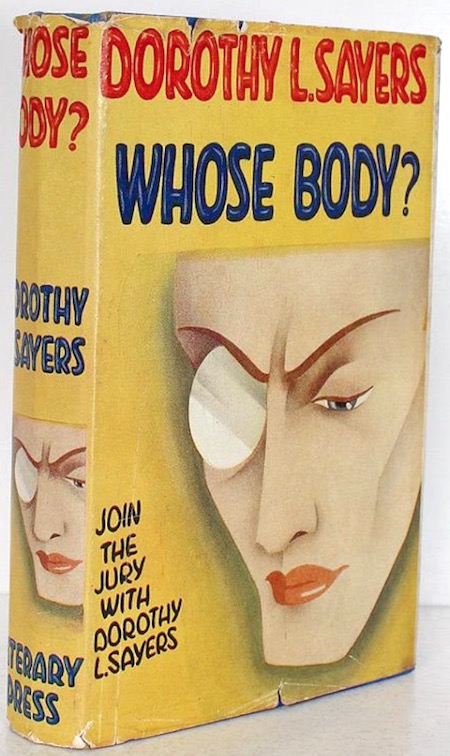

- Dorothy L. Sayers‘s crime adventure Whose Body? In the very first Lord Peter Wimsey adventure, Scotland yard detective Charles Parker brings his friend Wimsey along as he investigates a naked body which has turned up in the bath of an architect’s London flat. The dead man strongly resembles a missing Jewish financier… but Wimsey deduces (presumably, by noticing that the man is uncircumcised!) that this is not so. So who is this fellow, and what’s happened to Levy? Wimsey cracks the case — which involves an eminent member of London society who is secretly a lunatic with delusions of grandeur. Wimsey — the character was influenced by the high-spirited, literature-quoting protagonist of E.C. Bentley’s 1913 spoof Trent’s Last Case — is at his most antic, here. However, we learn that he’s suffering from WWI-related post-traumatic stress… which is why his friends and family encourage his sleuthing. Not one of my very favorite Wimsey novels, perhaps, but every one of them is fun. Fun facts: Sayers was one of the first women to get a degree from Oxford University. Wimsey’s first words in the novel, famously, are, “Oh, damn!”

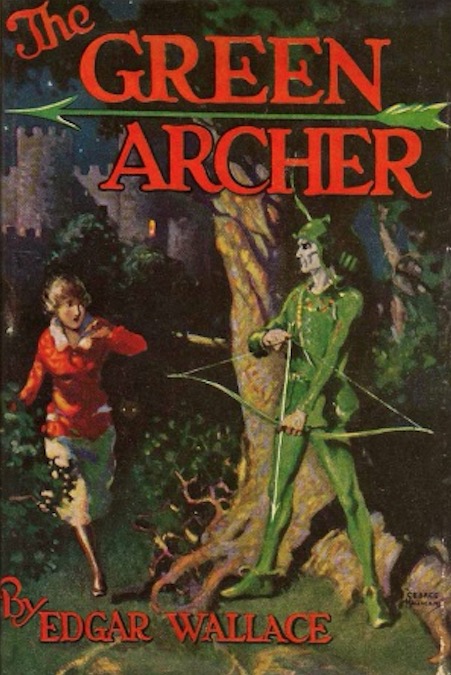

- Edgar Wallace’s crime adventure The Green Archer. Abel Bellamy, a wicked American who wishes to get revenge on everyone who’s ever thwarted his desires, buys a remote castle in England — one equipped with secret passages and a dungeon. There’s a legend about a green-clad archer haunting the castle, but Bellamy doesn’t let that bother him; the castle’s grounds and hallways are patrolled by a pack of vicious guard dogs. His brother’s wife, Elaine, should have married Abel — particularly after the brother died — but she didn’t, so she must pay the price. Then there’s Abel’s nephew, who went missing during WWI… but not before bequeathing his inheritance to an American who wants to use Abe’s castle as an orphanage. And what about Valerie, the beautiful young woman seeking information about her birth mother — information that Abel alone can provide? Wickedness is afoot, but so is a mysterious green-clad archer who begins to lurk near the castle, dispatching Abel’s dogs and henchmen! Fun facts: Adapted as film serials in the 1920s and 1940s, and as a German film in 1961. When Mort Weisinger created the comic-book character Green Arrow (for More Fun Comics in 1941), he took inspiration from the 1940s Green Archer serial.

- J.J. Connington’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Nordenholt’s Million (1923). As denitrifying bacteria inimical to plant growth spread around the world, causing agricultural blight, Jack Flint is invited to become director of operations at a huge survivalist colony located in England’s Clyde Valley. Flint discovers that his employer, the ruthless plutocrat Nordenholt, has blackmailed the country’s politicians in order to establish his stronghold, of which he becomes dictator in all but name. What’s more, Nordenholt’s henchmen purposely wreck what remains of British civilization, leading to scenes of horrific mass violence and agony; and the colony’s workers are treated like serfs. The plant-killing plague ends… but Nordenholt’s collectivized serfs refuse to work, blow up the factories on which their fragile community depends, and join weird religious cults! The author, it seems, was as worried about the Soviet Revolution as he was about right-wing politicians and rapacious businessmen eager to use any disaster as an excuse to dispense with democracy, liberty, and justice. Fun fact: Connington was the pseudonym of Alfred Walter Stewart, the British chemist who coined the term isobar as complementary to isotope.

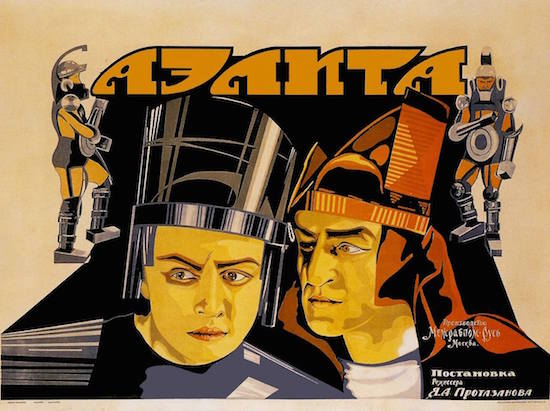

- Aleksey Tolstoy’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure Aelita (1923). After the Russian Civil War (1918–1920), a lonely Soviet engineer, Mstislav Los’, and a retired soldier, Alexei Gusev, travel to Mars in a rocketship. It seems that Earthmen have been there before: the Martians they encounter are the descendants of Mars natives and Atlanteans! The class divide between workers — who live underground, near their machines — and the ruling class (the Engineers) is severe. Worse, the planet faces environmental catastrophe; the Engineers’ (Jor-El-esque) leader, Toscoob, plans to destroy their city, in order to save the planet. While Gusev helps lead a worker uprising against the Engineers, Los’ — who has fallen in love with Toscoob’s daughter Aelita, the princess of Mars — works to help her father crush the rebellion. Fun fact: Aleksey Tolstoy is credited with having produced some of the earliest works of Russian science fiction. Aelita was adapted, in 1924, as a far-out silent film directed by Yakov Protazanov.

- John Buchan‘s historical adventure Midwinter. This novella is set during the Jacobite rising of 1745–46. Alastair Maclean, a captain of the army of Scottish highlanders that is preparing to march on London in support of Bonnie Prince Charlie, is traveling across England when he falls in with a “secret army” of non-political, pagan gipsies and “spoonbills” known as the Naked Men. Their leader, the wise, merry, fiddle-playing Amos Midwinter (a kind of Tom Bombadil figure), will end up rescuing Maclean on several occasions. In his introduction to a 2008 reprint of the novel, Stuart Kelly notes that Midwinter is an affectionate inversion of the most famous Jacobite novel, Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, i.e., instead of an Englishman tramping the Scottish wilds, a Scotsman explores the strange byways of Albion. Maclean befriends Samuel Johnson — i.e., the author who’d later compile the magisterial Dictionary of the English Language (1755). Maclean and Johnson, are bedeviled by traitors to the Jacobite cause… and they’re in both love with one of the traitor’s wives! Fun facts: Some consider this one of the best historical novels ever. I’m not so sure about that, but it appeared between two of my favorite Buchan yarns, Huntingtower (1922) and The Three Hostages (1924), so the author was certainly in good form.

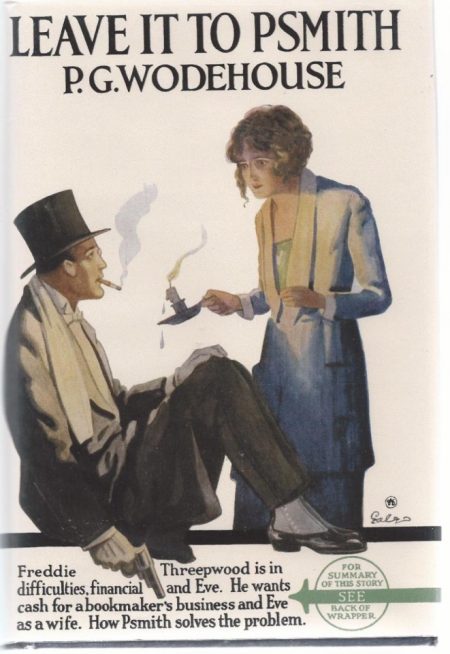

- P.G. Wodehouse’s comedic crime adventure Leave It to Psmith. In the fourth and final Psmith story, the monocle-sporting, adventure-seeking titular character has fallen on hard times; he has just quit a job working in the fish business. His school chum Mike Jackson, married to Phyllis (who incurred the wrath of her mother, Lady Constance, by eloping with Mike), is also barely scraping by as a school teacher. So when Freddie, son of the Earl of Emsworth (who is Lady Constance’s brother), suggests they steal Lady Constance’s necklace in order to free up some cash for Phyllis, Psmith tricks the Earl of Emsworth — who believes that Psmith is another of the freeloading poets his sister is always inviting to stay — into bringing him to Blandings Castle. There, he woos Phyllis’s charming friend Eve, who resists his advances… because she believes that he’s another friend’s husband (the poet). Soon enough, a real pair of criminals shows up to steal the necklace, and it’s up to Psmith to save the day! Fun facts: Psmith first appears in Mike (1909; in 1953, confusingly, the second part of this book was republished as Mike and Psmith), then in Psmith in the City (1910) and Psmith, Journalist (1915). This story was first serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1923.

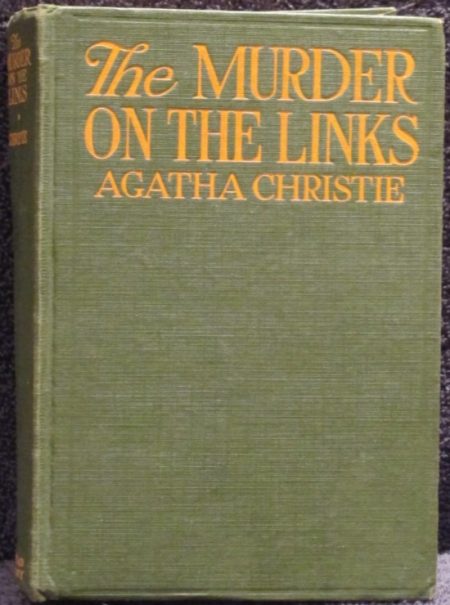

- Agatha Christie’s crime adventure The Murder on the Links. Hercule Poirot is a combination, or so it seems to me, of Arthur Conan Doyle’s three greatest characters: the brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes, the obnoxious and (literally) egg-headed adventurer Professor Challenger, and the gallant Brigadier Gerard — via whom Doyle satirized French and English manners. In this, Poirot’s second outing, the obnoxious, egg-headed, gallant Belgian detective is called to France — where a millionaire has been found murdered on a golf course. Why is the dead man wearing his son’s overcoat? Who was the love letter in his pocket for? Who was his mysterious visitor? Why did his neighbor suddenly come into a great deal of money? Accompanied by his young friend Captain Hastings, who was invalided out of the war after the Battle of the Somme, Poirot pits his wits (not to mention his capacious knowledge of murder cases) against not only the murderer (who strikes again) but a hostile detective from the Paris Sûreté. Fun facts: Christie purposely wrote the book in an ornate, high-flown “French” style reminiscent of Gaston Leroux; and she included a romantic subplot in which Hastings falls in love.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.