10 Best Adventures of 1968

By:

December 30, 2017

Fifty years ago, as of 2018, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Sixties (1964–1973) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Note that 1968 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Sixties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Sixties; the titles on my 1968 and 1969 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Sixties adventure writing is all about: self-reflexive, postmodernist, sardonic inversions of the adventure genre; plus New Wave science fiction.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any 1968 adventures that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Charles Portis’s western adventure True Grit. Mattie Ross, a narrator whose lack of humor makes the absurdities of her story’s larger-than-life characters all the more delicious, recounts her efforts — many years earlier, in 1873, at age 14 — to revenge herself upon her father’s killer, who has fled from western-central Arkansas into Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In Fort Smith, Mattie hires an aging, hard-drinking, one-eyed marshal, Reuben J. “Rooster” Cogburn; and insists on accompanying him. Her odyssey has been compared to Huck Finn’s, thanks to the gorgeous regionalisms and figures of speech it captures. Rooster and Mattie are joined by LaBoeuf, a self-satisfied Texas Ranger also seeking the killer — at which point the novel veers into crackerjack territory, as the old-timer demonstrates that “true grit” more than makes up for relatively clumsy, brutal craft. The action is bloody and exciting, but Mattie’s voice — intelligent, dry, cantankerous — is the real attraction here. Is this a revisionist western? I don’t think so. Instead, Portis (who didn’t consider this his best book) is demonstrating how western adventures should have been written in the first place. Fun facts: John Wayne would win a Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Rooster Cogburn in the 1969 movie adaptation; the 2010 Coen Brothers adaptation is excellent.

- Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s police procedural Den skrattande polisen (The Laughing Policeman). Why did a gunman kill eight people — including Detective Åke Stenström, from the special homicide commission of the Swedish national police — on a Stockholm bus? Stenström’s colleagues — including phlegmatic Martin Beck and left-leaning Lennart Kollberg — investigate. Despite tremendous political pressure — because massacres like this are extremely rare in Sweden — the cops painstakingly, even ploddingly follow one lead after another. Eventually, the come to suspect that the intended victim was Stenström — who in his spare time was investigating the murder of a Portuguese prostitute sixteen years earlier. This is the fourth in Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s so-called Martin Beck series; and it’s considered one of the best. Fun facts: The Laughing Policeman won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. The novel was adapted as a movie in 1973; set in San Francisco, it stars Walter Matthau and Bruce Dern.

- Samuel R. Delany’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Nova. In the year 3172, interstellar human society is divided into three constellations — each of which was originally colonized by different Earth socio-economic classes. Draco, which includes Earth and other wealthy planets, is an aristocratic constellation ruled by the (caucasian) Red family, whose Red-Shift Limited is the sole manufacturer of faster-than-light drives; the Pleiades Federation, a middle-class constellation, is the home of operations for the rival (mixed-race) Von Rays. The Outer Colonies, settled by working-class Earthlings, are the source of the important energy source illyrion, a superheavy element essential to starship travel and terraforming planets. Our protagonist is Lorq Von Ray, a playboy who — years earlier — was attacked and scarred by Prince Red. Now a nihilistic, revenge-obsessed adventurer, Lorq puts together an Argonauts-inflected squad of hippie-ish misfits — the Mouse, Lynceos, Idas, Tyÿ, Sebastian, Katin — and takes them on a demented voyage to the heart of an imploding star… in order to capture an enormous amount of illyrion, and in so doing destroy Draco’s control of the Outer Colonies. Though the plot is only intermittently thrilling (in a space-opera way), the language is gorgeous, the meta-textual references (to Moby Dick, Arthurian mythos, and more) are pretty fun, and there’s a whole Tarot-really-works conceit that’s almost persuasive. If Delany weren’t an experimentalist, this could have been a Dune; I’m glad it isn’t. Fun facts: There’s a cyberpunk tech aspect to the book that I can’t get into, here; William Gibson’s Neuromancer alludes to Nova. After this book, Delany didn’t publish again until Dhalgren appeared in 1975.

- Ursula K. Le Guin‘s fantasy adventure A Wizard of Earthsea. In the world of Earthsea, magic is an inborn talent — and those born with the most powerful gifts are sent to school on the island of Roke, where they are trained to become responsible, staff-carrying wizards. (Hello, Harry Potter.) Ged, a reddish-skinned shepherd boy, is trained by the humble mage Ogion to use his impressive powers in harmony with nature; however, Ged is impatient and reckless. (Hello, Ben Kenobi and Luke Skywalker — not to mention Qui-Gon Jinn and Anakin.) At Roke, Ged shows off to his fellow students by releasing a shadow creature that attacks him. Injured and afraid, he leaves school and seeks wizard work (including protecting a village from dragons!) while also evading the shadow creature, which continues to haunt him… until his old teacher, Ogion, advises Ged to confront his fears. Fun facts: This is Le Guin’s first book for a young adult audience; Margaret Atwood has called it one of the “wellsprings” of fantasy literature. The next two installments in the Earthsea Trilogy are The Tombs of Atuan (1970/1971) and The Farthest Shore (1972). Later books in the Earthsea cycle: Tehanu, Tales from Earthsea, and The Other Wind. In 2005, Le Guin expressed her disappointment when the Sci Fi Channel’s loose adaptation of the Earthsea trilogy cast a white actor as Ged.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. In a post-apocalyptic San Francisco, bounty hunter Rick Deckard is charged with “retiring” six escaped androids — one of whom, named Pris, moved into a derelict apartment building inhabited only by John Isidore, an intellectually challenged man who attempts to befriend her. Although there are plenty of thrills and chills here (for example, Deckard is seduced by an android whose mission it is to make it impossible for him to kill Pris), this is as much a philosophical novel about empathy as it as an adventure. The androids have no emotions — the only way that Deckard can tell them apart from humans is by giving them empathy tests. The androids, meanwhile, are on a mission to disprove a popular pseudo-religion called “Mercerism,” in which grasping the handles of an electronic Empathy Box allows you to “encompass every other living thing.” (“Mercerism is a swindle,” the androids insist. “The whole experience of empathy is a swindle.”) Deckard must prove them wrong… though he begins to wonder whether he, too, is an android. Fun facts: The theatrical-release version of Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s souped-up adaptation of Dick’s novel, doesn’t lead viewers to question Deckard’s humanity (or does it). And the 2017 sequel, Blade Runner 2049, further muddies the waters.

- Peter Dickinson’s YA sci-fi/fantasy adventure The Weathermonger. A teenage boy, Geoffrey, snaps out of a fugue state — in which he’s been for years — and discovers that he’s been working as a “weathermonger” for an English village on the Channel… but now they think he’s a witch, and they want to kill him. He and his younger sister, Sally, escape across the water to France. What’s going on? Several years earlier, a mysterious force has converted most of England’s population to anti-technology zealots, and the country has reverted a quasi-medieval way of life. Unaffected people have fled for the continent. France and other European countries have been unable to figure out the cause of the “changes,” and adults who’ve parachuted in to investigate haven’t returned. So Geoffrey and Sally return to England, and drive a 1909 Rolls Royce Silver Ghost — whose workings are described in loving detail — towards an atmospheric disturbance emanating from the Welsh coast. Fun facts: Hopefully it isn’t giving too much away to reveal that this book — not so much the other two in the trilogy — concerns what’s known as The Matter of Britain. Chronologically, this is the final installment in Dickinson’s excellent Changes trilogy; however, it was published first.

- James Blish’s fantasy adventure Black Easter, or Faust Aleph-null. A fascinating novella about an arms dealer who hires a black magician, Theron Ware, to assassinate California’s Governor “Rogan” before unleashing all the demons of Hell. In this alternate Earth, sorcery and the ritual magic for summoning demons, as described in Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna (1305), say, or the Enchiridion of Pope Leo (c. 1633), work. That’s kind of the whole plot, but the framework of rules and regulations within which the magicians operate is persuasive; and Ware is a compelling character. His description of black magic as a science and an art reminds me of my own field, commercial semiotics: “Given [the right] books, you could learn almost everything I know in a year. To make something of the material, of course, you’d have to have the talent, since magic is also an art. With books and the gift, you could become a magician… in about twenty years. If it didn’t kill you first, of course…. It takes that long to develop the skills involved.” A group of white magicians — named after sci-fi authors, ha ha — are powerless to intercede. Fun facts: A version was serialized as Faust aleph-null in If magazine. Black Easter, often published with its sequel, The Day After Judgment, is part of the After Such Knowledge trilogy — which concerns the unanticipated consequences of the search for new knowledge.

- Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain YA fantasy adventure The High King. The final installment in Alexander’s terrific Prydain cycle begins shortly after the events of Taran Wanderer. Dyrnwyn, the magical black sword of Gwydion, Prince of Don, has been stolen by the necromancer Arawn. Tara, Gwydion, Eilonwy, Fflewddur Fflam, Gurgi, the hapless Rhun, and even the peaceful pig-keeper Coll head out to retrieve it. Their quest turns into an all-out assault on Arawn’s kingdom — the Fair Folk, the northern realms, and the Free Commots, the smiths and weavers whom Taran befriended while seeking his own identity, the creatures of air and land all flock to the banner of the White Pig. Characters we’ve come to know and love don’t survive; magic fades. What will become of Prydain — and Taran, Assistant Pig-Keeper? Fun facts: The High King was awarded the 1969 Newbery Medal for excellence in American children’s literature.

- Lionel Davidson’s political thriller Making Good Again. James Raison, a British lawyer representing the daughter of Bamberger, a long-missing German-Jewish banker, arrives in West Germany to settle a reparations case with the government — which was a controversial topic at the time. (The book’s title is a literal translation of the German term for the restitution payments made to Holocaust survivors.) There are two other lawyers on the case: Heintz Haffner, a German who claims he avoided joining the Nazi party; and Grunwald, a rabbi and lawyer from Israel who has a lien on some of Bamberger’s money for a refugee organization. Bamberger’s money was deposited in a Swiss bank in 1947 — what happened to it, and to Bamberger? Wearing disguises and traveling through the Bavarian forest, Raison and his unlikely comrades confront echoes of Nazism and ponder questions about German guilt. All of which sounds deadly serious — but it’s also thrilling, and funny. Fun facts: Davidson, a British-born Jewish writer who served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and eventually moved to Israel, won the Crime Writers’ Association Gold Dagger Award three times.

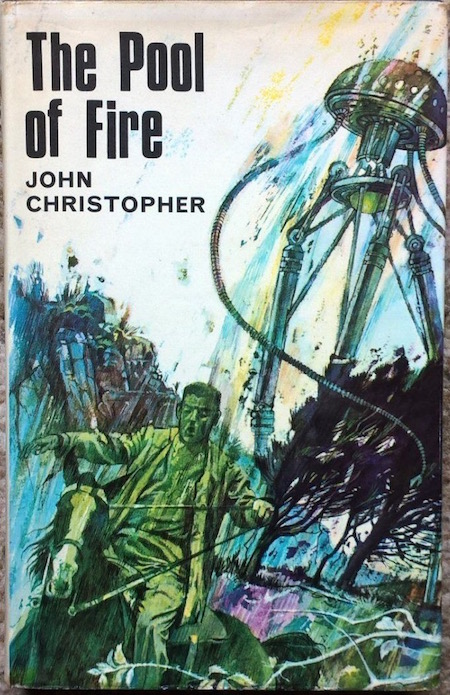

- John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The Pool of Fire. In the thrilling conclusion to Christopher’s Tripods trilogy, young Will helps organize resistance against the alien invaders who’ve subjugated the human race… and then the uprising begins. Will, the series’ flawed protagonist, has spent months inside one of the Tripods’ domed cities (as detailed in the previous book, The City of Gold and Lead); now, he and Fritz travel across Europe and the Middle East setting up anti-Tripod terrorist cells. Once the Resistance discovers that alcohol has a strongly soporific effect on the aliens, they plan a simultaneous commando raid against all of the Tripod cities on Earth. The Panama city holds out… so Will, Fritz, and Henry lead an attack launched from hot air balloons. One of the friends sacrifices himself to destroy the final redoubt. Now that their common enemy has been vanquished, will humankind remain united — or will they revert to national rivalry and war? Fun facts: The Tripods trilogy was serialized in comic strip form in the Boy Scouts’ magazine Boys’ Life, from 1981–1986. John Christopher (real name: Sam Youd) is also the author of the terrific Sword of the Spirits trilogy (1970–1972).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.