THIS: The Allegories of the Stage

By:

November 6, 2017

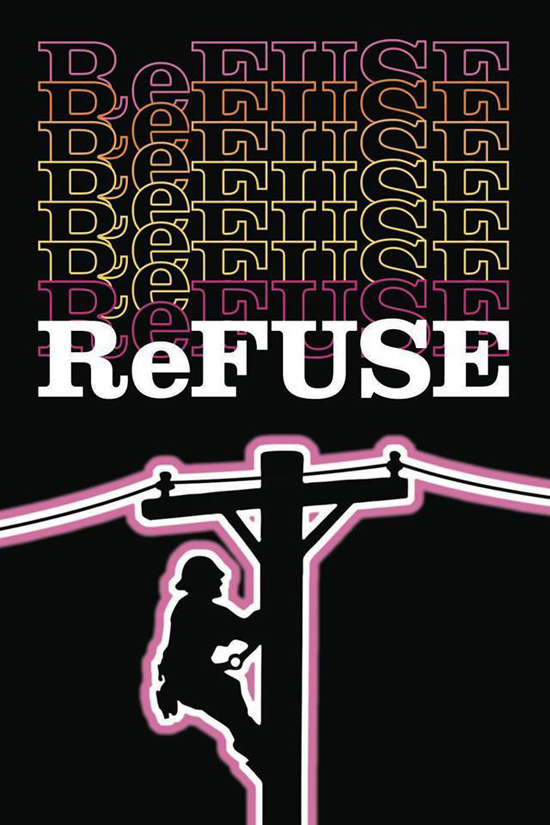

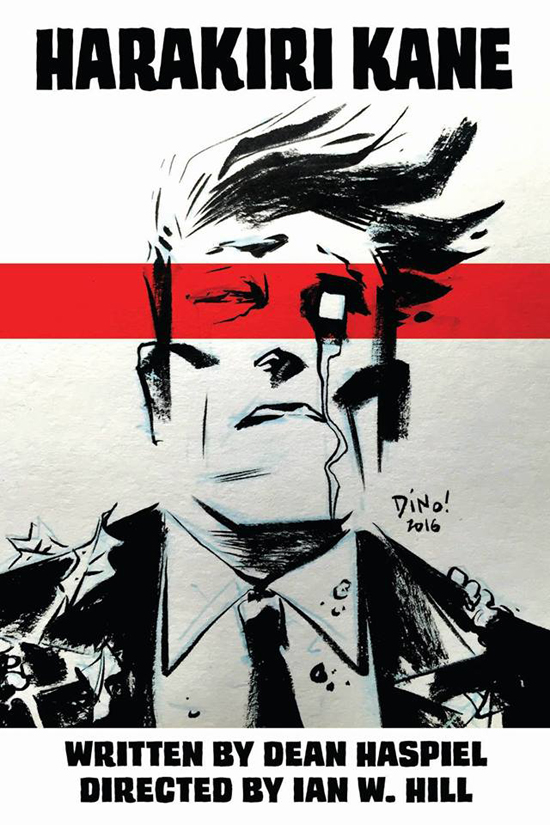

Being an inquiry into Gemini CollisionWorks’ Twentieth Anniversary of Hysteria on the occasion of its newest theatrical episodes, ReFUSE and Harakiri Kane.

Ideas, enthusiasms and ways of life end up on the scrapheap of history with gathering speed and mounting volume. But most of our garbage won’t decay for half a millennium, if then. Resources dwindle, the recorded past piles up, and the 2016 election showed that there’s nothing you can’t expect to wash back in on time’s tide.

ReFUSE is a sift for diamonds in this social wreckage, and a reclamation of the memorable but ephemeral fruits of the Gemini CollisionWorks performance company’s now 20 years of experimental yet inviting production. Earlier works, like Gemini’s sardonic live movie-serial Spacemen From Space, picked out the cosmic jokes and overlooked virtues in disposable culture, but ReFUSE bravely leaves all the pieces where they fell. There’s always more of the past, and this play lays out a planet-full of memento mori to make sense of.

We’re in a Dreamtime, or, maybe Primetime, where a triad of modernist deities — The Detective, The Broadcaster, The Architect — try to write a future for a world of misplaced morals and murderous mutual caricatures. They watch over a pantheon of stereotypes — a gangster, a cowboy, a spacewoman, a general, a pirate, a foreign femme fatale, a scientist, a princess and a product mascot — contents of a cosmic Fisher Price toy set or puppet-show which doesn’t point to much outside its box. Mystic threes once held the universe in place; the three Norns spun, wove and cut our lifelines; three TV networks bounded the life and death of our minds. In an altar-like pile of obsolete means of communication (film-reels, plugin mics, etc.), The Architect at one point picks through what look like threads, but the fabric is permanently tangled, and there’s nothing at the end of the puppets’ strings.

True to all end-times fables, the survivors fall back on ritual; in this case, the endlessly rotating cache of pre-digital media, providing material for incanted infomercial bromides, desperate variety revues, hypnotic dance-party scenes and gladiatorial gameshow reenactments. The Broadcaster calls the tunes from a totemic satellite, The Architect provides relentless optimism and compulsory structure, and The Detective tries to piece together how society fell and when we lost our sense of shared survival. In-between leaning on “suspects” in some absurdist live-action cross of Murder on the Orient Express and a Clue game, she does desk-duty trying, in the grand tradition of cops the real-world over, to fill in the gaps by just making stuff up. Hers is a scriptural typewriter, on which she tries to set the stage for a new kind of human continuity, but most of these ideas, too, crumple in her hands and head for history’s wastebasket.

The play’s narrative collapses and unfolds again like serial big bangs; the cast and spartan set are orbited by vintage projections and ambient soundbites; and in one fugue-ing motif, a string of badly acted ads for a defunct NYC chain of clam bars flash up, featuring mandala-like servings of pinwheel seafood. Big Advertising was infamous in the 1970s and ’80s for the urban-legendary promotional image of a plate of fried clams supposedly airbrushed to subliminally suggest an orgy, and the cast’s hysterical pitch and danse-macabre maypole choreography invoke collective chaos that knows not what it looks like.

The perennially littered stage and eerily enforced exuberance of some of the ensemble’s talkshow and song-and-dance rituals put me in mind of the planet-wide silt of “kipple” and the perpetually-running Buster Friendly and His Friendly Friends show in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?; though a late lurch from diversion to discourse puts the play’s contemplations of cultural turmoil and turning-points into some talking-head characters’ mouths Goldstein’s Book-style, and an even later soliloquy by one character sets out a moving memory of lives unified and dreams sparked by the golden age of analog mass-media. ReFUSE may have retrieved something precious after all.

Director/writer Ian W. Hill’s panoptic frame of reference, fluency in multiple theatrical voices, and tarot-hands of shifting and reforming meaning are all at a pinnacle here. His encircling aural design, one part post-traumatic trigger to one part cartoon sound-effect, once again creates lavish invisible sets and implied histories. Holly Pocket McCaffrey’s costumes uphold the company’s heritage of silly dress-up in hellish contexts. A series of songs with lyrics by Hill and music by the troupe’s technical mastermind Berit Johnson strike a similarly balanced cognitive bargain, spanning ballad-showstopper, operetta, and torch with savage scrutiny and superlative sincerity.

Of a cast who all masterfully hold more than one identity in their minds simultaneously, the especially enduring archetypes include Rolls Andre’s finely modulated mania as playful obsolete pirate, uneasily omnipotent gameshow host, and post-apocalyptic pundit; Zuri Washington as tragically dedicated and disillusioned space-explorer and glazed-over public-TV moderator; Linus Gelber as deadly vaudevillian science-authority and sleazy chat-show sidekick; Amanda La Pergola plying her one-woman genre of tortured slapstick and elegant dismay as a knockoff Disney princess; Philip Cruise as bottomlessly one-dimensional midlevel military officer, oily latenight interrogator, and the guy who soliloquizes about sleeping with the TV on and sharing a cherished viewing ritual with his mom; and Alyssa Simon as The Detective in a dizzying wardrobe of different shticks, satirizing every shade of self-importance while, back at the desk, seeming like thought itself personified, in both intellectual folly and imaginative genius. Olivia Baseman, La Pergola, Anna Stefanic and Washington all contribute to the talent-show portion with authentic pathos, ferocious wit, and stratospheric chops that could get all of them smuggled onto Broadway before it had a chance to catch the hack.

The cycle begins and ends with the characters covered in sheets, the naptime of reason, like classic statues still to be completed or ones shielded from debris, Schrödinger’s cast, each with a candle-light under the veil that flickers on and then off again like distant, long-dead, possible stars. We ask the same questions endlessly and think ourselves sane. But we have to keep listening, in hopes of the one time the echo answers in a voice that’s not our own.

It’s not how you live your life, it’s how you outlive it, or live it down. Comic writer/artist Dean Haspiel (full disclosure, a collaborator and crony of mine) has lived several artistic existences, without once yet falling on his face in-between. In his second incarnation as a playwright, Harakiri Kane (the first was Switch to Kill, in 2014), Haspiel contemplates lives lived poorly, or well enough alone. It’s parenthetically subtitled Die! Die, Again!, but the Russ Meyer hysteria and hardboiled melodrama promised by that title (and delivered, epicureanly, by Haspiel’s previous play) is a lifetime ago. This is pop-philosophy with no pretension yet unimpeachable insight; a dive-bar Wings of Desire.

The above and below are both accounted for, however. Though most of Harakiri Kane takes place in the shadows (bars, boxing rings, industrial wastelands, funeral homes), it begins in the sky. We’re in the Himalayas, where an explorer named Orlagh is climbing a mountain to enact an ever upward aspiration after receiving a diagnosis of imminent death. She’s on a tower that will fall short of heaven, talking to lost and burdensome lovers and then to a long-frozen corpse, forced to stage entire conversations on her own (a performance of desolate tenderness by the always heartbreaking or electrifying Alyssa Simon).

Having only yourself to remember your story to is tragic, but more so if you don’t even know how it goes. Harry “Harakiri” Kane, an ex-boxer who starts shambling through the narrative when we cut from mountaintop to alleyway, takes a while to even recover his own name. He’s the kind of tabula rasa through which fate can get itself written (in the tradition of mysterious or amnesiac champions from The Man With No Name to Demon With a Glass Hand). We come to learn that he is one of many forgotten men and women, walking a path between existence and oblivion and roaming the land of the living, visiting strangers near to the moment of their death. Haspiel’s modern metropolis is still populated by archetypes from as far back as penny dreadfuls and as farther back as mythic antiquity, like the death-worshipping, human-butchering chef Jack (played in haute dudgeon by director Ian W. Hill), and the corps of beat-walking Valkyries to which Harry now belongs.

The world feels like all of us are stepping over bodies anymore, and escape from either the danger they face or the duty it calls upon is inconceivable. For Harry, it’s also not possible — trying to release himself through suicide never works. Others of his kind don’t try at all, either renouncing the physical for philosophical pursuit (Nicodemus, a suave and subtly frightened portrayal by Rolls Andre), or making a pastime of testing themselves for vestiges of human feeling (the wistful, fearless storyteller Sharon, a poignant and powerful stage debut from Jessica Stoya).

As played by Alex Emanuel, Harry is in the grand tradition of poetic palookas from Wallace Beery onward, and his stubbled, square-jawed countenance and scuffed, haggard grandeur make him a Haspiel cartoon come to life, in a brutally sensitive performance that’s staggering in more than one sense. His instinct is to be an angel of mercy, befriending doomed losers like the barfly and desperate bankrobber Joe (played in myriad shades of mournful, mischievous resignation by Linus Gelber), but Harry’s curse is to be the one left standing.

“We only get one chance to die, and I screwed it up somehow,” Harry says at one point, and his crime seems to be trying to reject his destined narrative — he’s the soldier who disobeys orders, the epic warrior who has declined his role.

The script Haspiel has written for him suggests there might be a virtue he holds on to and a way to claim its reward, but nothing will be gained easily. Hill and collaborator Berit Johnson keep the guignol gore startling yet sparing, and Hill’s staging and pacing are stark without austerity, brooding but never overbearing; having created painterly noir before, with his comicbook scenarist he achieves an eloquent, tensely alive sketch.

Sharon watches mortals through entire lifetimes and writes stories of her own lives unlived. Like Orlagh at the play’s beginning, she alone is left to tell her tale, a holy text or mythos to fill the blank page of her past. She is the last being we see, and the end of the story is expressed beyond words…a shout in the dark, echoing the pain of birth and the feeling that connects us to the earth. Harakiri Kane sacrifices everything for its artistry, and wipes the canvas clean for any new life story to begin.

All photos: Mark Veltman

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE