THIS: Little Green

By:

September 18, 2017

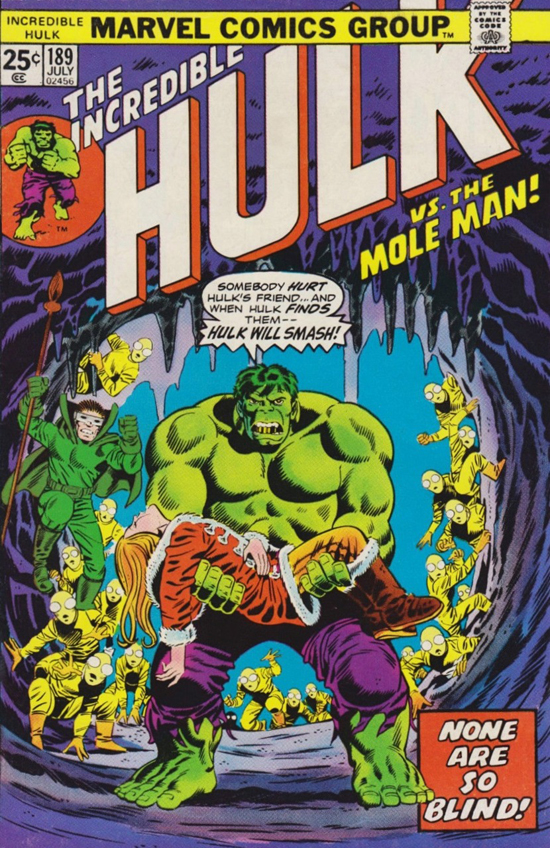

For all the bodies of work I most love and study in comics of the 1970s (Kirby, Gerber, Buckler’s Deathlok, Goodwin & Simonson’s Manhunter), if I have a single favorite issue of any comic from that decade, it’s “None Are So Blind…!” from The Incredible Hulk #189 (July 1975).

There’s much being said these past two weeks about the contributions its writer, Len Wein (who died on September 10) made to comics by co-creating the market-dominating Wolverine and the artform-advancing Swamp Thing, as well as hiring Alan Moore to further revolutionize comics with the latter character and then editing Moore & Gibbons’ Watchmen. Tucked into the dependable but unremarkable stretches that Wein more typically did on many of the most recognizable series at both Marvel and DC, was a hallucinatory run on the Hulk which remains the work of his that means the most to me.

That book was always a world apart from the rest of Marvel, the one surviving strain of the 1950s giant-monster books that made them money before the ’60s superhero re-boom. Wein and pop-art poet of the grotesque Herb Trimpe ran with that, in a bizarre string of stories about Cold War mutants, extraterrestrially enhanced escaped convicts, backwoods monstrosities and interdimensional angels.

I have fond memories of “Hammer and Anvil,” a variant of Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier’s Defiant Ones who break loose from the rest of their chain-gang, happen upon a detoured, injured alien and fill his chest with bullets, upon which he thanks them for the lifegiving metal supplement and gratefully transforms the chain between them into a magic-tech golden lasso/garrote. This upgrades their rampage capacity, while pathos ensues in a collision with the estranged, Bojangles-variant father of one of the cons, and the father’s new best friend, the Hulk.

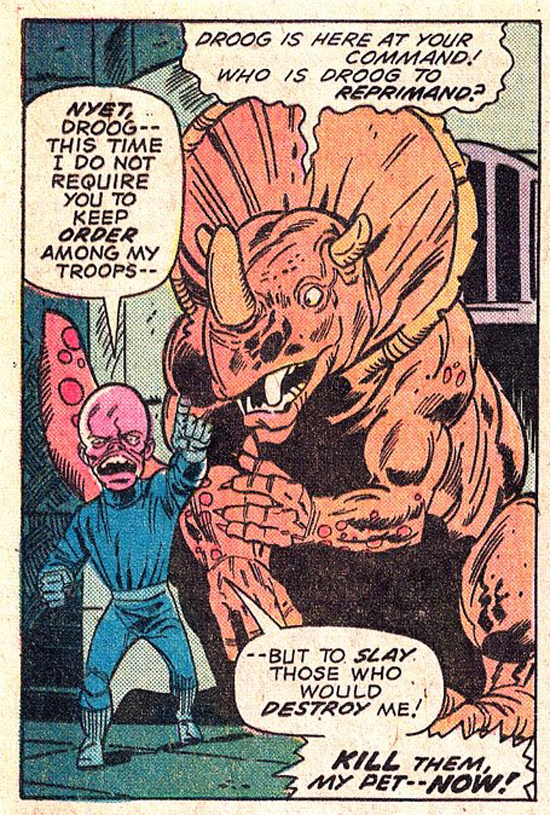

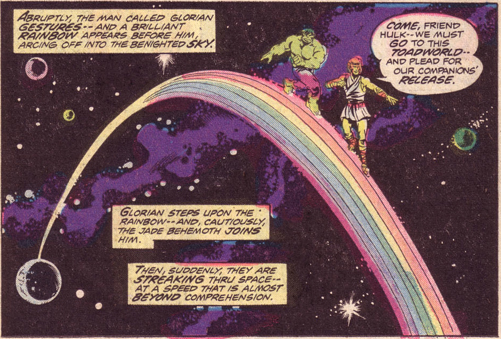

I can never forget The Gremlin, mutated, mind-controlling Soviet warlord, and his pet talking triceratops, who speaks entirely in verse. The reality-warping, (be-careful-what-you-)wish-granting Glorian is high on my personal listicle of sci-fi saints along with Lightray and the Silver Surfer.

Amidst these adventures/ordeals, in which The Hulk would roam from Appalachia to Canada to Siberia to the American Southwest in a kind of displaced-person parable — also often waking up unawares in the newest locale like an allegory of alcoholic blackouts — the Hulk finds himself taken in by a family in a remote area of Russia, where a serum from unique local plantlife that could restore a young girl’s sight is stolen by the subterranean, shadow-dwelling Mole Man. Not being able to see the Hulk, the girl senses his capacity for kindness and befriends him; when his mission succeeds and her eyes open again, she subjectively sees him as a handsome paragon, but he flees the family in tears, only able to conceive of himself as a monster in contrast to her and her family’s grace.

The Comics Code decreed that “good” must always triumph, but never said that a story couldn’t end in the hero’s emotional destruction — indeed, impossibility of redemption, at least in his own eyes — though it wasn’t something any reader had seen before, and this image of the good deed being punished by the very person who did it was more like the psychodramas of the midcentury theatrical stage than anything else on the magazine shelves. The humanization of the Russian family, taken for granted within the story, was revolutionary right beyond the page in those days of stereotypes frozen solid by the Cold War. And most innovatively, it was the first story told from within the caverns of the Hulk’s own troubled mind — first-person, in captions; not only risky in conveying the character’s cloudy thought-patterns with clarity and credibility and without “full retard” ridicule in that insensitive era, but perhaps the first instance of the voiceover device which, in the current century, has become ubiquitous in superhero and other genre comics.

“None Are So Blind…!”’s cover was reproduced on the Mead three-ring binder I held onto from 5th through 7th grade. It’s said that the Hulk, along with Batman, was Wein’s favorite character to write. There’s tragedy in internalizing what’s been expected of you, as our antihero can’t help doing when he banishes himself from the family that could love him. Breaking through all boundaries with the Hulk, Wein could be Wein. And in this sad fable, I could look through the monster’s tears to see why I should be myself.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE