THIS: My Back Issues

By:

August 28, 2017

Comicbooks are one of the purest forms of time travel — even though they may tend to get trapped there themselves. Much has been said about how the medium’s very form plays with time, freezing moments into boxes while creating a template we can omnisciently see the whole of. Its content can travel in loops as well, especially with action, fantasy and superhero franchises. Spider-Man has to stay young, even as his past mounts up. Graphic visionary Grant Morrison has argued for a recognition of “comic time,” in which iconic characters’ mythos just accumulates like tree-rings, rather than an impossible linear lifeline with constant reboots and rebrands. The fittingly named All Time Comics travels in the opposite direction; rather than expanding the histories and casts of long-running franchises, it collapses decades into a short-run series of heroes you’ve never heard of, with histories built-in.

All Time is the farthest that literary comics publisher Fantagraphics has ventured in the direction of hardcore superheroics, though the details go deep as well. Conceived by filmmaker Samuel Bayer and his brother, renegade cartoonist and art-educator Josh Bayer, and produced by Josh and outsider-genius pulp draftsman Benjamin Marra, the six-issue set supercollides several other talents from each end of the graphic timestream. Bookending the series at issues 1 and 6, the opening chapter uncovers the last, best work of bravura art-brut midcentury mainstreamer Herb Trimpe (still the artist most people think of when they think of The Hulk), while the closing issue showcases the brisk, baroque drama of indie auteur Noah Van Sciver’s laconically sensationalistic style; two true treasures of lost and found comics history. Between them, we see the muscular work of Bayer himself and a lot of the wry, meticulous spectacle of Marra (who also co-writes some issues).

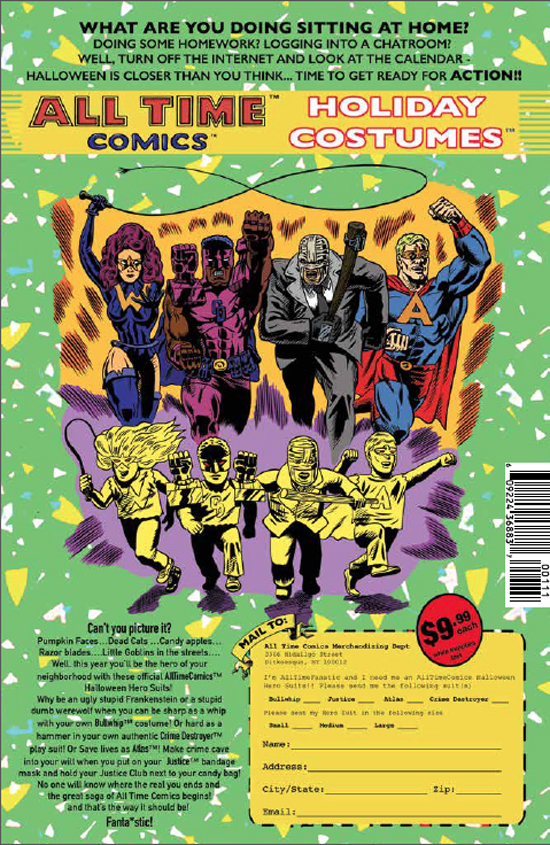

The set introduces us to four main characters, in several randomly numbered issues of their separate sagas; this conveys the mystique of the mass-market comicbook’s wilderness years before the specialty-shop and the internet, when kid readers would piece together the intermittently distributed disposable pop like dead-sea scrolls; for us latter-day adults, it also forms a kind of fragmentary graphic-novel which is, itself, about what it’s missing.

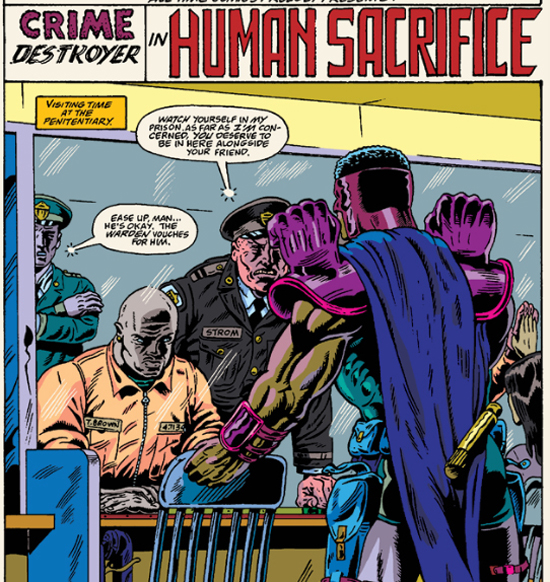

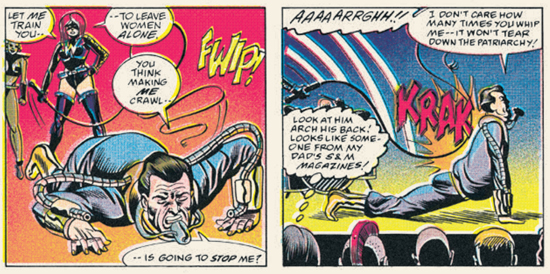

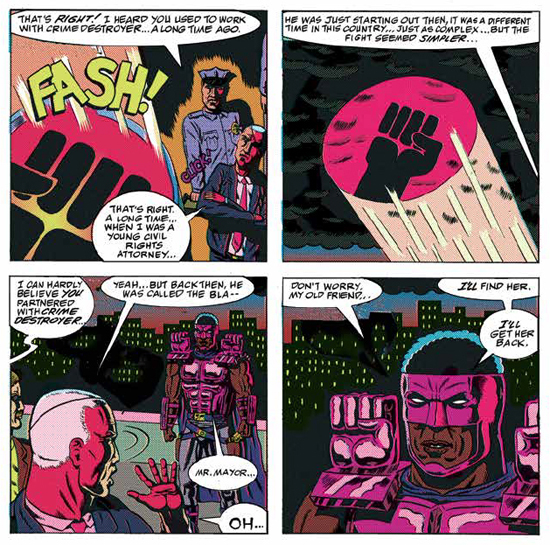

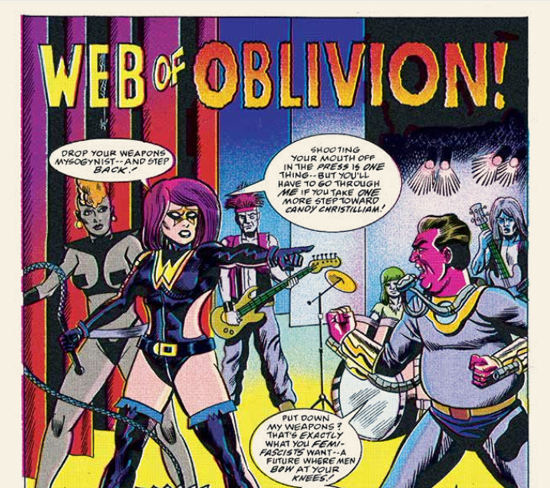

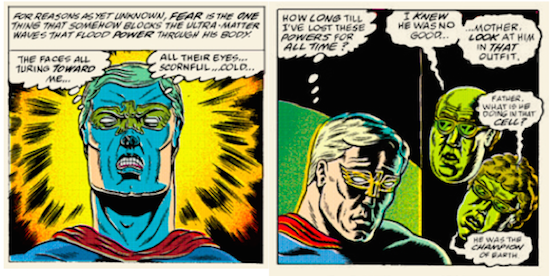

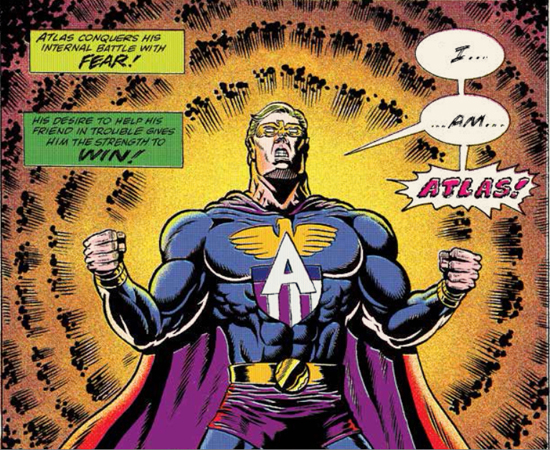

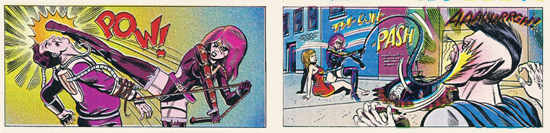

Under the banner of a fictional company from a speculative 1970s/’80s (or the perpetual now imbued in any unfamiliar artifacts found for the first time), we come across: Crime Destroyer (an armored vigilante whose persona seems to process the PTSD of ’70s combat vets, from the real-life perspective of the Black soldiers who did the majority of the dying, though seldom seen in the peacenik comics of the time); Atlas (who dresses like an angel but seems an embodiment not of heavenly grace but White guilt, with an Achilles heel of self-doubt which can only be countered by raging confidence); Bullwhip (a pro-bono dominatrix for the dispossessed who turns fetish stereotypes on their head and knocks alpha-males on their asses, adding in the ideology that cheesecake action-icons from Charlie’s Angels to Pam Grier were just missing); and Blind Justice (a variant on the Death Wish archetype wrapped in bandages to efface any of the original’s racist dynamics, and emptied of an identity so as to signify the soullessness needed for vengeance and the elusive neutrality we wish for in public order).

Having gotten advance looks at the whole series and seen four issues reach the shelves as you read this, I skyped with Josh about the personal passions and historical precedents that made him and his collaborators feel that this comic’s time had come…

HILOBROW: How do you situate this project in the continuum of affectionate satire or reclamation of childhood loves? And do you have a method for immersing yourself in that past, while staying tethered to the knowingness of today?

BAYER: I think it’s impossible from the inside to say if you’ve done that successfully… sidestepping a lot of the current methodology of doing comics seems like a good idea. That doesn’t mean you can’t do good comics using the contemporary voice, but all I know is, I’ve absorbed a huge… I spent decades reading old comics from the ’70s and ’80s. I spent a lot of time over the years absorbing Michael Fleisher, Bill Mantlo, and especially Mark Gruenwald, as far as underappreciated mainstream creators, and… the voice I adopted is kind of like, what’s left after you eliminate a lot of the contemporary approaches to doing comics. For me, these were the comics I knew — I wanted to go about it kind of sincerely. And the effort to make a good, entertaining comic was what I had in mind. Because of the talent I was bringing onboard, I knew there’d be a lot of other layers to it.

HILOBROW: “Sincerely” is a good word. When I first read Crime Destroyer, I was struck by how straight-faced that book was — as far as meta and self-reference goes, the niche I imagine this series filling is that our world is still in the ’70s, and these are the comics that publishers would be producing. There are still layers that seep through, and the further you read in the six issues, the more serious and self-aware it gets (as in Atlas’ over-the-top soap-opera alongside genuine psychodrama), until with the final Blind Justice we’re at almost Miller-level morality-play.

BAYER: I had somebody come up to me at the L.A. Zine Fest and say, “I love these comics, I wish more people knew about them, because a lot of people haven’t heard about them,” but also, “the people who do know about them are really confused by them — they don’t know what to expect from them, they don’t know where they’re going.” When we presented this comic, it wasn’t that we went to Fantagraphics and said, “Let’s do the most ingenious superhero project of all time, one that fits Fantagraphics’ methodology and their high, rigorous, critical standards.” The way the project evolved was, my brother — who’s sort of a mentor, and put me through school, and who has wanted us to do a project for a long time — came to me and said, “I have this idea, where I have four superheroes” (originally it was three), and he said he wanted to tell a story where he did them in the present, as a film, and I did them in the past.

So this is kind of a preamble to a film that he has in mind; he probably doesn’t want me to reveal too much about it, but it’s sort of in the tradition of films that deal with the gap between truth and legend — the roles of folk heroes, and the gap between the mundane reality and the icons we make them into. So as part of this world that he wants to build, he wanted to seriously try to do these comics, and he said, “I want them to be like real ’70s comics.” So it’s not, necessarily, like an auteur thing where I had this vision and wanted to do this project. He pitched it, he said “here’s how much of a budget I have,” and I knew I could attract real creators who would be a dream to work with. He thought I could do it, and I welcomed the challenge of trying to see if I could manage to do a vehicle for self-expression that was in this retro mold.

HILOBROW: You can, if you’re really sincere and committed to it.

BAYER: Especially when you have as much freedom as I do on this project.

HILOBROW: Speaking of which, what is Fantagraphics’ attitude toward this? It’s arch enough that it didn’t strike me as too far off that this would be a Fantagraphics book, but then again, it has a fidelity to its sources that’s way beyond art-pulp counterparts like Dan Clowes’ The Death-Ray for Drawn & Quarterly, etc.…

BAYER: I think they’re divided. I think half of the staff is into it, and half of the staff, you’d have to ask them about it. But not everybody has to like the project. Eric Reynolds has been very supportive, and we’d even like to get him to ink some of it, but he has enough other stuff to do.

HILOBROW: All Time is probably the project of this type that most feels like it could actually have stood on its own in the era that it homages. Even something as masterful as Alan Moore’s 1963 feels… not like Marvel exactly, but definitely like one of the responding Marvel knockoffs of the period, like Tower or Atlas/Seaboard. You did your syncretic work well, because none of this feels like a one-for-one takeoff on any specific comics or characters.

BAYER: That may be luck, or maybe a synergy among different creators. When Sam brought the concept to me, he had Atlas, with the fear, the fatal flaw built in. He had Crime Destroyer, with his history of having had his family slaughtered when he came back from the war. He had less with Blind Justice and Bullwhip. Bullwhip was almost a blank slate, and that’s maybe one of the reasons that she ended up not having a secret identity — but that’s also kind of an advantage, because we could just play with her being Bullwhip all the time… in fact we could’ve done that with all the characters, and it might have been…not more interesting, but interesting in a different way, because the reader would be on the outside a little bit more.

HILOBROW: It made sense to me, since Bullwhip hangs out with a thinly fictionalized Wendy O. Williams, that the Bullwhip identity isn’t even a costume, it’s just her club look. [laughs] But I think you play with identity even for the three heroes who have alter-egos; the body of Blind Justice’s former self is portrayed as just a vessel for this strange spirit of retribution that’s taken over, and Crime Destroyer’s armor is like an Iron Maiden closing in his emotions, and Atlas’ civilian identity feels like even more of a momentary, changing-room screen for his true mythic persona than Clark Kent.

BAYER: Did you ever read this Frank Miller Daredevil comic, it’s called “Badlands”? It takes place in Jersey, in this little sleazy town… it reads like a Jim Thompson novel; he’s never in the Daredevil costume, but he’s not Matt Murdock either… he doesn’t wear the sunglasses, so his blind eyes are in the story… he’s just a stranger who comes into town, and it does have mystical overtones, as if… there’s a dead cop in the story, and he came back to avenge him, and people say, “When I look out the corner of my eye I think you’re him.” He leaves his milieu, goes to some other environment, and it’s kind of a commentary on identity; like you were saying, he’s just a vehicle for vengeance and justice in the story. And he’s not Daredevil and he’s not Matt Murdock, so it does raise interesting questions about, who this guy is.

HILOBROW: That also raises the interesting concept of a fictional hero’s setting being part of their costume — that there’s a certain frame they can’t be taken out of, or, if they are, they become someone else.

BAYER: That was my concept for that second Blind Justice story; that the first half of it would be in the city where we usually see him, and then, this manhunt so obsesses him that it takes him way into the wilderness. When I wrote it in my head, I wanted it to have that scene where he’s gone so far from food and shelter that he’s unraveling —

HILOBROW: — literally [laughs]

BAYER: — he’s been in the woods for two weeks and his urban-commando outfit is coming apart…

HILOBROW: Yeah, that scene is like his un-creation, like a reverse Genesis — his Eden was the city, and he expels himself from that. There’s a troubling soliloquy from the villain of that piece, about “natural” law favoring the predator, while Blind Justice personifies the civilized law that exists for the unprotected. You and I know that this series was in process long before this year, but it happens to rhyme uncannily with political concerns that have gotten louder again with the Trump era, as in that story, and with other elements like the vaguely-defined white supremacist cult Crime Destroyer meets in the first issue. Were any of those issues specifically on your mind going into this… or was this just a mix of the kinds of subjects that self-conscious ’70s comics tried to tackle?

BAYER: I went with the themes I like reading about the most, that I’m most interested in. I’ve always been really, really obsessed with reading about prison life and the American prison system. My brother, the star of the company, who funded the company, he’s been very successful, but he actually was in jail once when he was younger, for some kind of drunken teenage shit with a car. So, maybe as a kid — my brother’s almost like my father, he kinda raised me — so maybe it started there, I dunno. But I’ve always, for a lot of different reasons, read as much as I can about prisons. Also, [I think about] the way convicts are such outsiders to society, and they’re figures of alienation. So, people in prison are really hungry for identity, and that’s a lot of what’s going on now with this weird white-supremacist shit going mainstream; it’s like this fringe culture, which very much is a part of prison culture, is strangely becoming more and more of the larger world.

I think there’s a prison plot-point in every [All Time] comic, except maybe one… so I just went to that stuff. When I write, I’m more about getting into personal issues, and reworking trauma from the past, and getting into things that frustrate me or have some sort of emotional resonance with me. So I don’t feel like I have to go to, “what’s the issue that people are buzzing about?” — I try to find a personal way to connect, and it doesn’t matter if that connection isn’t immediately significant to anyone else.

HILOBROW: That’s a good articulation of how these stories can be refractions of what we’ve actually gone through. Glen Gold has a cogent essay about how he sees post-war PTSD having worked its way into Jack Kirby’s oeuvre. Which circles around to what we were saying about even pulp and genre comics being a conduit for self-expression. These things come out no matter what, and it’s almost safer to have them come out in the form of absurd fantasy than autobiography sometimes.

BAYER: Jim Thompson was hired to work on movies, and it’s said that every one was a real struggle, he could never turn in a screenplay that was less than 200 pages [smiles], and they’d have to cut it and move him along and give it to a different writer. While in his own work [as a novelist], he’s able to get to a very personal kind of interior mental space. He’s usually writing about some weird crime heist, or a love triangle, or a “Mexican standoff” or all three — and they always feel like he’s talking about some kind of personal psychological glitch which is way, deep at the core of his being. So that’s where he had his freedom, was in his mainstream writing.

HILOBROW: In that era, for many artists, commercial work was the only route for this personal stuff to travel, and some could suppress it more than others… Kirby was one of the masters who could forge those feelings into something that was as entertaining for audiences as it was cathartic for him…

BAYER: There’s a lot of stories I don’t really go into, publically, and maybe eventually I’ll go into some in my art, but — where I came from was bad. The situation was bad, the parenting was bad, the prospects were bad. So all of that still feeds into everything. My friend Sabin [Calvert], who also did some background inking on one of the comics, was talking about how that sense of poverty is missing from a lot of media. He said he was watching The Simpsons Movie, and there was a sequence where Homer wins a car by doing some kind of loop-de-loop at a carnival, like, if you can make your motorcycle go all the way around this loop you get a car. They don’t have any money, they have to get this car or the family fails; and they win the car. Then in the next scene all the tension’s gone, they just go to a 7-Eleven and they’re just buying gas, and he was like, “’Wait a minute, they didn’t have any money!,’ and it hit me that the people creating this show have had everything they’ve needed for decades; that economic reality is kinda missing from their consciousness.”

HILOBROW: It’s a lack of knowledge that’s especially perilous as Americans flail in their understanding of why who voted for whom. You’ve told me about having to scrounge for comics as a kid; is there a layer of implied autobiography in the way that the All Time comics are deliberately out of sequence?

BAYER: Right, the point where you’re like, “I’m gonna go to my deathbed wondering what happened in the first half of this comic.” [laughs] I was reading some blog today about this guy reading Captain America in the ’60s, and being so confused, when Captain America is in The Avengers; he’s like, “This is a character from the ’40s!?” — he missed the issue where they flashed back and the character is rescued from suspended animation. There’s a million instances like that, and it’s kinda cool, the period where you didn’t have everything you needed to know at your fingertips — that’s a negative thing in so many ways, but it’s a special thing too. I remember when I was in fifth grade, I picked up X-Men… #139. It was two issues after Jean Grey had died, and there was a panel where Scott was looking into the sunset and seeing Jean, and talking about how she was dead, and I was, like, in a trance about it, and I just had no idea what had happened, and I had to track down that issue. But I gotta say, when I got Ben [Marra] involved, my brother was pitching some ideas, and one that Ben really connected with was to do the issues out of sequence. Doing them out of context was really fun for him.

HILOBROW: Ben also has a unique mix of sincerity and wryness when he approaches all of his material, so I thought he was the perfect accomplice.

BAYER: He is, and he’s got the common touch; I’m an acquired taste, but everybody comes alive when they see Ben’s stuff. Some people hate it, but most people really respond to how painstakingly he’s re-created the chops that those old guys had. He just really delivers, in a way that, even if somebody doesn’t like his stuff, they usually respect it.

HILOBROW: There’s something sculptural about the way he draws; as in much ancient Egyptian art, you’re always aware of the block it was carved out of, so to speak — however dexterous and animated his figures get, you’re always aware of the right angles, almost as if these panels are friezes. It’s like when Grant Morrison once praised to me Kirby’s “non-naturalistic” writing style — what some see as clumsy can be a legitimate, abstracted way of perceiving things. Ben is one of those artists who have a better-than-real style — so meticulous, it’s like a pulp pre-Raphaelitism, where you can see every chrome pipe instead of every blade of grass.

BAYER: We like that look, that approach to comics, a lot. We like the stiff, almost Chick-tract approach. Ben has said that “fluidity is overrated” [laughter], that’s such a great point.

Collect every issue of All Time Comics here.

Images (top to bottom):

1. pencils: Josh Bayer; inks: Al Milgrom; color: Alessandro Echevarria

2. pencils: Herb Trimpe; inks: Benjamin Marra; color: Alessandro Echevarria

3. art: Benjamin Marra

4. pencils: Benjamin Marra; inks: Al Milgrom; color: Matt Rota

5. art: Benjamin Marra

6. film: Samuel Bayer; actor: Denise Schaefer

7. pencils: Noah Van Sciver; inks: Al Milgrom; color: Matt Rota

8. pencils: Benjamin Marra; inks: Al Milgrom; color: Matt Rota

9. art: Rick Buckler; color: Alessandro Echevarria

10/11. (both:) art: Benjamin Marra; color: Matt Rota

12. art: Benjamin Marra; color: Matt Rota

13. film: Samuel Bayer; actor: Lamonica Garrett

14. pencils: Benjamin Marra; inks: Al Milgrom; color: Matt Rota

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE