IMAGINARY FRIENDS (3)

By:

August 22, 2017

One in a series of ten posts reprinting HILOBROW friend Alexandra Molotkow’s profiles of figures who’ve loomed large in her personal pantheon.

Originally published in The Believer, July 2014

On April 7, 1963, soon after the Beatles released Please Please Me, Cynthia Lennon lay in a public maternity ward at Sefton General Hospital, in Liverpool, England. It had been a lonely pregnancy: John hadn’t been around much, and, having been told that her existence might jeopardize the band’s success, Cynthia had mostly stayed home “knitting bootees” for the future Julian Lennon. Men weren’t as involved in childbirth in those days. As she approached her second day of labor, the Beatles performed in Portsmouth and the woman in the next bed screamed for her mother.

Julian was born the next morning. When John showed up, days later — “Cyn, he’s bloody marvelous!” — he had them moved to a private room, but it featured a window overlooking a corridor full of onlookers. “The room felt like a goldfish bowl and it was obvious John couldn’t stay long,” Cynthia writes in her second memoir, John. “He hugged me and signed dozens of autographs on his way out.”

John and Cynthia had fallen madly for each other as students at the Liverpool College of Art, where he’d been a sharp-tongued teddy boy and she a prim, shy girl with dreams of a quiet life teaching art. She bleached her hair like his dream girl, Brigitte Bardot, and he wrote her heartsick letters (“I love you like GUITARS”). She was thrilled to witness the rise of the Beatles, but the bigger they got, the less she saw of her man.

In swinging London, Cynthia felt like “a naive girl who had simply gotten lucky and didn’t deserve to be there.” She hoped John would come around to domesticity, but by the time the Beatles stopped touring, he was restless and — thanks to LSD — more at home in dimensions she couldn’t access. Meditation had seemed like something that might bond them, but when the Beatles set off for a retreat in Bangor, Wales, in 1967, she fell behind with their luggage. The train departed, leaving her weeping on a platform popping with flashbulbs. “The incident seemed symbolic of what was happening to my marriage,” she wrote. “John was on the train, speeding into the future, and I was left behind. As I stood there, watching the train disappear into the distance, I felt certain that the loneliness I was experiencing on that platform would become permanent one day.”

By then he’d met Yoko Ono, whom Cynthia had felt more puzzled than threatened by until, in the spring of 1968, she returned home from a holiday in Greece to find the artist on the floor of their sunroom, wearing, as Cynthia recalls, Cynthia’s robe. Within a month, the new couple was public and beaming, and Cynthia had been cut out of John’s life “like a gangrenous limb — total amputation from all that I had been or known.”

“John’s trajectory towards someone like Yoko was blazingly obvious all along,” wrote Michel Faber, in a scathing review of John for the Guardian, “but even today, Cynthia clings to rosy memories… In cherishing the cosy evenings when the family would ‘cuddle up in front of the TV,’ she unwittingly corroborates John’s own dismissive recollection of ‘a happily married state of boredom,’” as if Cynthia were an albatross that the world had suffered vicariously. And maybe it’s true that the world had more of a claim on him than his first wife did.

“The truth is that if I’d known as a teenager what falling for John Lennon would lead to,” read John’s final lines, “I would have turned round right then and walked away.” Aside from the living death of losing her husband abruptly and in public, Cynthia never recovered the life she could have had without him. Her life had been defined by her first marriage, meaning the world had defined her without seeking her input. She’d been pegged as the little woman with a spine like a rubber hose, her role in history frozen at the very moment her heart broke.

Subsequent husbands were sometimes too impressed by her famous ex, and in times of necessity — her divorce settlement was low, measured against his fortune, and she had a child who wasn’t getting a lot from him financially or otherwise — she had to resort to capitalizing on her surname. “Do you imagine I would have been awarded a three-year contract to design bedding and textiles with the name Powell?” she told an Independent reader in a Q&A. “Neither did they. When it is necessary to earn a living, it is necessary to bite the bullet and take the flack.”

The narrator of John is muted and deeply sympathetic — “the kind of woman you’d have a chat with in a food queue in the supermarket,” says Caro Handley, who wrote the book with her, “and go away thinking, ‘Oh, what a nice person.’” Of course, the John and Yoko legacy is more inspiring, more in keeping with the icon as lovingly remembered, but if history has made Cynthia the anti-Yoko, John represents her finding the virtue in this. “Cynthia, a Nice Person without imagination,” Faber writes in his Guardian review, “is simply not equipped to analyse the man who wrote ‘Imagine.’” But he missed the point. John is not just a book about John Lennon; it’s a memoir by a woman who was married to him.

Rock stars are the gods of the last century, avatars for the emotional and religious yearnings 1960s youth would have had nowhere else to place. Bob Dylan’s cryptic magnetism marked him as the Person With the Answers; Mick Jagger’s shaking hips stood for personal and sexual liberation. “Mick Jagger personified a penis,” wrote Pamela Des Barres, the famed groupie and author of several books, in her 1987 memoir, I’m With the Band: Confessions of a Groupie. As a teenager, she “rushed home from school every day to throb along with Mick while he sang: ‘I’m a king bee, baby, let me come inside.’”

Getting in close proximity to a rock star, then — for a night, or a string of tour dates, or the time it would take them to compose an album especially for you — would seem a service to a higher power. “Perhaps by embracing their cherished rock gods, groupies tap into their own divinity,” Des Barres wrote in 2007’s Let’s Spend the Night Together: Backstage Secrets of Rock Muses and Supergroupies. Unfortunately, rock stars are not gods but rather human beings whose feelings happen to resonate with millions — feelings inspired by other human beings, some of whom have written memoirs. These books are often disregarded as attempts to cash in, but while the books are sometimes bitter, they’re rarely cynical. Taken together, they comprise a shadow history of classic rock, an account from within the aura and at the margins of the rock star’s hero journey.

In many cases they describe an experience less like beatification than a slow, stifling ego death. This is “the most curious and lamentable fate of the pop star’s girlfriend,” Marianne Faithfull says in her 1994 memoir, Faithfull, written with David Dalton. “On the one hand you are elevated to the enviable role of Idol’s Consort. On the other hand your life becomes fair game for the press, the public and the star himself to do with what he wishes… When your personal pain becomes material for songs and the songs become hit singles, the process is strangely unnerving, however flattering it may at first seem. But then again, what else could the poor bastard have done?”

The rock star’s lover is public but powerless. Not only public, but relevant: some part of her is part of the music that fans live their lives to, as well as the mythology that helps give the music its power. To love a rock star is to become a rock star’s invention, and, secondarily, the invention of a public obsessed with the life of the rock star. The fans might love you by association, but their compassion ends where your troubles begin.

The fan clichés about John Lennon are true: he was a deserving icon who put more good into the world than bad, and his relationship with Ono, whose power matched his own, was a resonant art piece. When you’re hailed as a god, your human flaws seem monstrous, your missteps shake the earth, and the world is ravenous for the contents of your wastepaper basket, your garburator, your septic tank. Ex-loves could write books about you; ex-chauffeurs could write books about you. Worse than having the aura, though, is being flattened by its pull.

Rock and roll was never a friendly place for women; the female Mick Jagger did not get to be Mick Jagger. In her biography Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin, Alice Echols describes a life spent shuffling between brief professional triumphs and bone-wracking loneliness. While Joplin had a two-and-a-half-year affair with San Francisco boutique owner Peggy Caserta — author of her own ex’s memoir, Going Down With Janis — it was on and off, and hardly committed. At the end of her life, Joplin was engaged to a man described as a “con artist” who slept with other girlfriends in her bed, and claimed to consider her music “mediocre.”

Though Caserta cared deeply for Joplin, she worried about falling too hard. Another girlfriend of hers had had her heart broken by Joan Baez. When her songs played on the radio, “it’d be like a sledgehammer hit her in the chest,” Caserta told Echols. “And I thought, How am I going to escape this woman’s voice? I just didn’t want to take a chance on feeling a dagger in my heart so deep that I might never be able to pull it out.”

No matter how iconic she became, Joplin was always judged as a woman: audiences embraced her talent but never forgave her for using it. Jagger and Lennon were met backstage by adoring fans willing to do anything for their company, but while Joplin had her fun, Echols describes a scene that typifies her frequent desolation: after acing her New York debut, at the Anderson Theater, Joplin found herself alone as her bandmates in Big Brother and the Holding Company went off to party. She wandered to a dive bar, where a journalist approached her; as she complained to him about the guys in the group, he “fantasized shutting her up with the ultimate put-down: ‘You forget you have acne.’”

The sensitivity of male egos, the demands of motherhood, and the general disdain for female ambition made loneliness the likely lot of the chick singer; for the young, female rock-and-roll fan, the arm of a male musician might have seemed more welcoming. Girlfriends and wives appeared as fairy-tale heroines who held royal sway in the courts of their rock-star loves. Even groupies — at least “the concubine elite,” as Des Barres put it — lived a preteen dream, consummating their crushes nightly while avoiding the emotional and physical perils of being married to, say, Keith Moon.

For the teenage Des Barres, being a rock star’s girlfriend might have seemed to promise the glories of rock stardom itself: the admiration of millions, sexual gratification (the reason so many men pick up guitars in the first place), and the opportunity to inspire great work, whether by chipping in or just gracefully exhaling. As Echols notes, Rolling Stone’s first real acknowledgment of women in rock was a special issue on groupies (in which Des Barres is featured). “All I knew was that I wanted to be somebody,” writes Bebe Buell, singer and former rock girlfriend (who partly inspired the character Penny Lane in Almost Famous), in her 2001 memoir, Rebel Heart: An American Rock ’n’ Roll Journey, written with Victor Bockris. “That somebody resembled Anita Pallenberg, Pattie Boyd, Marianne Faithfull, Jane Fonda, Brigitte Bardot, and Janis Joplin!”

Buell got her start as a Ford model, though she preferred late nights at Max’s Kansas City to early-morning call times. “I harbored a secret ambition to be a rock star,” she writes, but she wouldn’t put a band together until the ’80s. In 1972, she moved in with Todd Rundgren, and “by 1973, I didn’t have a career. I was Todd Rundgren’s girlfriend; that was my fucking career, thank you very much.” The following year she posed nude for a Playboy centerfold, a shoot that made her “the most sexually desirable girl in rock ’n’ roll,” and her body became an accolade: Mick Jagger, Jimmy Page, and Rod Stewart played out professional rivalries through attempts to seduce her. “Simultaneously, it also flushed my American modeling career down the toilet.” There are consequences, financially and otherwise, to not having your own work.

Pattie Boyd was a model and a fixture of swinging London when she was cast in A Hard Day’s Night, in 1964. On set, George Harrison asked her to marry him, though he settled for a date; they were wed two years later. Like Paul McCartney’s girlfriend at the time, actress Jane Asher, Boyd valued her career and independence (she found it hard to relate to Cynthia, a full-time mom whom she liked but found “rather serious”). But George never fully approved of her working — “I suspect he was simply a product of his upbringing,” she writes in her 2007 memoir, Wonderful Tonight: George Harrison, Eric Clapton, and Me, written with Penny Junor — and so Boyd dialed back on the jobs she took, settling on photography as a hobby. “When I gave up modeling I lost an important part of my identity, my feeling of self-worth, my independence, and my self-confidence.”

After the Beatles split up, George seemed to withdraw, and Boyd was feeling lost and neglected when Eric Clapton professed his love and presented her with “Layla” — “the song got the better of me, with the realization that I had inspired such passion and creativity.” Her life with George was “fueled by alcohol and cocaine” and rent by extramarital affairs; she left him to join Clapton on tour in 1974. But Clapton’s affection seemed to manifest only in grand gestures. As their relationship deepened, so did his drinking, and so did hers, along with her feeling of worthlessness. (She inspired at least two more Clapton compositions: “Wonderful Tonight” and “The Shape You’re In.”) “He had his creativity — his work, his recording, his traveling — and I had nothing. I was taking photographs but I had little else.”

After Clapton had a son by one of his mistresses — “I thought my heart was about to disintegrate,” writes Boyd, who hadn’t been able to conceive — she finally got up the nerve to leave him. But after twenty-five years as a rock star’s woman, she was unprepared for the real world: she’d never paid a phone or electricity bill, and she had to relearn how to ride the tube, where she feared being recognized, and where enormous posters of Eric bore down from every station. At parties, when strangers asked what she did for a living, she told them: nothing. “In losing Eric I had lost my role, and if I wasn’t Mrs. Clapton anymore, who was I?”

While frank and emotionally vivid, Boyd’s memoir is daintier than Angela Bowie’s Backstage Passes: Life on the Wild Side with David Bowie, written with Patrick Carr, which is raunchy, effusive and sometimes brilliant, full of gossip spun in verbal pirouettes. Angela reflects bitterly on her marriage, which she claims to have seen as a job: Early in their relationship, when he was still a struggling musician, “I offered David a deal,” she writes. “He and I would stay together, I said, and embark on a joint course: First we would work together to accomplish his goal — to make his dream of pop idolatry come true, to make him a star — and then we’d do the same for me; we would power me into a career on the stage and screen. David listened to me, then said, ‘Can you deal with the fact that I’m not in love with you?’”

In the early days, by her account (and those of others), Angela served as David’s “door-kicker” and unofficial creative director, helping to inspire and shape the more far-out elements of his presentation, as well as negotiate his business dealings and sort out the minutiae of his routine. He became a star, of course, and she enjoyed the fruits of their lifestyle (she seems to have matched him for conquests of all genders), but the biggest boost her acting career got from his camp was an audition for a Wonder Woman role that, unbeknownst to her (and David), had already been filled—a scheme engineered by his management to promote his “1980 Floor Show” episode of the TV series The Midnight Special.

“Angie Bowie was every goddamned bit as important as David Bowie,” says Pleasant Gehman, rock writer and consort, in Let’s Spend the Night Together. “She was the person who had songs written about her. Angie’s art was just to exist.” Unfortunately, a career in existence offers little financial security outside of a divorce settlement, and the work it helps produce is generally credited to someone else. “It was beginning to dawn on me that if I was Mary Shelley, where was my Frankenstein?” Faithfull writes of her end days with Mick. “I was very contemptuous of women who just hung around groups like the Rolling Stones. I wasn’t doing anything.”

It’s work to style yourself for the cameras, to project the combination of poise, glamour, and irreverence befitting a rock star’s wife. As a model, Boyd was compensated for beaming out such an ideal, but her problems began when this ceased to be her job and became, instead, her essence — when she lost the rights to her own image. The irony is that she could be the subject of great art while feeling, or being made to feel, as though she wasn’t producing anything. “To have inspired Eric, and George [Harrison] before him, to write such music was so flattering,” she writes. “Yet I came to believe that although something about me might have made them put pen to paper, it was really all about them.”

“‘What are we going to do with you?’ [Albert Grossman] used to say to me,” writes Buell. “‘You’re a star, but what can we make you do? You’re a star! But what are you?’” Between gushing about her rock-star crushes, Des Barres wrote in her diary: “What I really need is to feel accomplished. I bet people like The Beatles and Leonard Cohen feel accomplished.” Though she recorded an album with the GTOs, an all-female group mentored by Frank Zappa, a hoped-for tour with Rundgren never came to pass.

Ultimately, it was writing her memoirs that turned Des Barres’s experiences into accomplishments and made her famous in her own right. Pattie Boyd’s memoir — along with her photographic exhibitions, including Through the Eyes of a Muse, made up of pictures from her rock-and-roll years, which toured internationally — gave her a profession, and made her a historical actor rather than just a character in history, a subject with an inner life rather than a romantic notion ladled from some rock star’s beautiful imagination.

In April 1965, Marianne Faithfull was an eighteen-year-old pop singer with a hit single. She was also pregnant and engaged to be married, but her fiancé was out of town when “God Himself” — Bob Dylan — checked into London’s Savoy Hotel. Faithfull joined the hoards of musicians, writers, and hangers-on crowding his suite while the “mercurial, bemused center of the storm” typed away, nearly oblivious to them all. Faithfull was too nervous to say much, but a few days in, she writes, she was told that Dylan had been writing a poem about her, and found herself “elevated to Chief Prospective Consort.” Dylan’s girlfriend, Sara Lownds — about whom Faithfull knew just enough to pity her — was elsewhere.

Late one night, after the entourage had cleared out, she was granted a private audience with Dylan. He played her his latest album — pausing after each song to ask if she understood it — and finally made a pass at her, but while she found him “devastating,” she demurred. “It’s my Primal Anxiety. Being so overwhelmed by someone that I would lose my self. This awful fear of sex + genius + fame + hipness all building in a cumulative ritual. I was terrified that I might simply vaporize when all these things came together.” To that, she writes, he ripped up his papers and threw her out.

A constant menace in these stories is the threat of obliteration, as the author struggles to stay whole in the great vortex of her lover’s stardom. Faithfull recalls the thrill and horror of watching her soon-to-be boyfriend perform in 1966: “Almost from the first notes of ‘I’m a King Bee’ an unearthly howl went up from thousands of possessed teenagers. Girls began pulling their hair out, standing on the back of their seats, pupils dilating, shaking uncontrollably… Mick effortlessly reached inside them and snapped that twig.” One-on-one, she found Jagger much less intimidating than Dylan, and the couple shared an idyllic first few months before she was found wearing a fur rug during the 1967 drug raid on Keith Richards’s Redlands estate. Strange rumors circulated involving a Mars bar, and while Faithfull had felt like “one of the boys,” the press painted her as “the woman… the lowest of the low… the slut. Miss X.”

Faithfull’s powerlessness in the court of public opinion — and beneath the Stones juggernaut — tormented her; so did the world’s mistaken idea that she was living out their fantasy. Jagger, in her description, was a fine boyfriend, but her withdrawal into drugs and self-abuse feels like a form of retaliation against his kingliness: he was a Rolling Stone, she was the girlfriend thereof, and no amount of affection would have changed the fact that she was living on the wrong terms. “I left him for a romantic ideal,” she writes. “I wanted to be a junkie more than I wanted to be with him.” By 1972, she was living on a bombed-out wall in Soho; in 1979, she emerged with her own Frankenstein: the album Broken English.

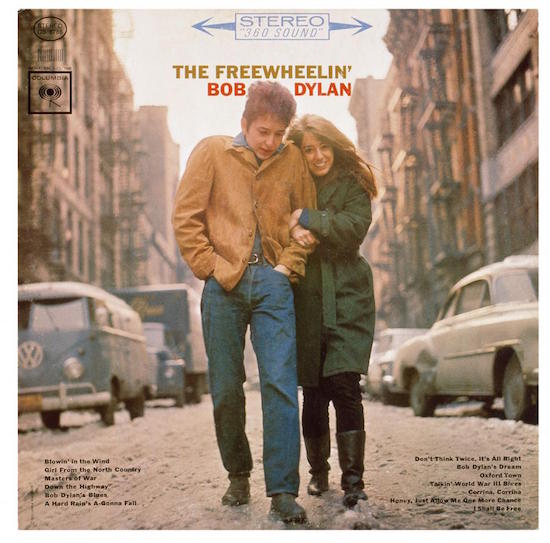

At the Savoy Hotel, Faithfull imagined Dylan’s girlfriends as “women whose souls… had been sucked dry by breaking the taboo and copulating with the god, and who were now condemned to wander in a ghostly procession through expensive hotel lobbies: Joan Baez, Suze Rotello [sic]. Zombies of the Mystic Bob.” Rotello — actually Rotolo — was Dylan’s first love, the woman on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and while she survived the relationship, she suffered terribly as her boyfriend emerged as God himself.

Rotolo was seventeen when she met Dylan at a concert at Riverside Church, in New York City. A “red diaper baby” from Queens, she knew art and politics and had grown up in the Greenwich Village folk scene; she introduced Dylan to works and ideas that would become part of his sensibility. When she left New York to travel and study in Italy, her eight-month absence inspired a string of love songs, including “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

While abroad, Rotolo read Françoise Gilot’s Life With Picasso, and had an epiphany. “I felt I was reading a book of revelations, lessons, warnings,” she writes in her book, A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. “…[Picasso’s and Dylan’s] personalities were so similar it was astounding. Picasso did as he pleased, not worrying about the consequences for the people around him or the effect his actions had on them. He took no responsibility, clarified nothing, came to no decisions and did nothing that would have made it possible or easier for the various women he was involved with to leave him and get on with their lives. He was a magnet, and the force field surrounding him was so strong it was not easy to pull away.”

Rotolo had no desire to fold her life into Bob’s; she saw their relationship as a meeting of equals, no matter that, in their scene, a woman was considered “a string on [her man’s] guitar.” But when she returned to New York, she realized that her life had already become material, and that the locals were not sympathetic to Bob’s abstraction of her: “Some deliberately sang songs he had written about his heartache as well as any ballad that pointed a finger at a cruel lover… It was as if every letter Bob had written to me and every phone call he had made had been performed in a theater in front of an audience.”

She was disturbed by the mob that charged his limousine after his Carnegie Hall appearance in October 1963, by his werewolf-like metamorphosis from songwriter to prophet. As their private problems became more and more public, and the motives of those around her more suspect, it dawned on Rotolo that Bob Dylan’s Girlfriend was lying in pod form, soon to replace her. “One afternoon I was in a café with a friend and he mentioned someone who had said something complimentary about me,” she writes. “I laughed and told him that people were nice to me only to get close to Dylan. He looked at me and said, Don’t you think someone might genuinely like you because you are you? ‘I doubt that very much,’ I replied.”

By 1964, Rotolo had nearly reached the event horizon of Dylan’s celebrity. After a slow, painful breakup, she worked as an artist and activist, married and had a son, and avoided speaking publicly about her ex until after he published his own memoirs, in 2004. A Freewheelin’ Time was published in 2008, just three years before she passed away. In the introduction, she describes Dylan as “a presence, a parallel life alongside my own, no matter where I am, who I’m with, or what I am doing.” She may have been one of the last people on earth to see him as human.

Rotolo’s book, like Faithfull’s, is a very good memoir on its own merits, and in both cases the stars discussed are less interesting than the speaker. Faithfull seems to have always lived in a myth, and she describes the most squalid abjection with lucid remove, as if reliving her life as a ghost. Rotolo’s book is less an inside story than a strolling impression of a significant time and place — she emerges less as a character than as a warm gaze — and it contains her sensibility, which, in the early ’60s, happened to run alongside Bob Dylan’s.

John Martyn’s Grace and Danger is a breakup album, with accompanying lore: recorded between crying jags and desperate calls home, it’s a murky, disquietingly subtle eulogy for his ten-year marriage to Beverley Kutner, with whom he was still in love. The two met in September 1968, when Beverley was a twenty-one-year-old folk singer with a bright future ahead of her: her rich, knotted voice had earned her the support of Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, who had invited her to perform at the Monterey International Pop Festival the previous year, as well as Joe Boyd, who produced some of England’s most interesting acts and had assembled a superb lineup for her debut album, to be released by Warner Bros.

“Is it Sod’s Law,” Beverley Martyn writes in her 2011 memoir, Sweet Honesty: The Beverley Martyn Story, “that just when things start to go right, the gods send a cosmic spanner that lands smack bang in the heart of the works?” That spanner was John, a baby-faced performer from Scotland with “the eyes of a Botticelli angel” and a beautiful way with the guitar. They married the following April, and as their relationship evolved, so did his role in her music.

The two were recording in Woodstock when, Beverley writes, a run-in with Bob Dylan after a charity gig sent John into a jealous rage. He shoved her, she says, and, back at home, hurled a fork at her eye. “If I’d known what was in store for me, how many times that scenario of violence followed by remorse would be played out, I’d have run screaming into the night and never looked back,” she writes, “but that’s the wonder of hindsight. That night the weather broke and there was a massive storm. And so Stormbringer! was born,” billed to John and Beverley Martyn, pictured cuddling sweetly under gathering clouds on the album cover.

The two recorded a follow-up record as a duo, The Road to Ruin, but John — who, she writes, had started taking more than his share of the songwriting credit — decided to tour on his own, setting up a career as a brilliant, troubled iconoclast and leaving her at home with the kids. By the mid-’70s, Beverley had all but given up on her own career while John drank, philandered, and traveled. She’d come to dread his return. “Over the years I received a broken nose, a fractured inner ear and hairline fractures of the skull. One night he smashed a chair over me and my arm was damaged when I put it up to protect my head from the force of the blow. John wouldn’t even let me call a doctor, let alone go to the hospital… ‘Get back into bed,’ he’d snarled, ‘or I’ll throw the baby out of the window.’”

In 1979, Beverley fled in her oldest son’s boots and flagged down a car. John wrote his breakup album, which, she notes, includes some of her lyrics and melodies; Beverley, still processing the years of abuse and struggling to keep the kids fed without financial support, had a breakdown. When a women’s magazine published a favorable review of one of his albums, Beverley called its offices in desperation and told her story to the editor, who offered only platitudes: “I couldn’t go public with my story because I didn’t think anybody wanted to hear it.”

Beverley dictated Sweet Honesty to her friend Jaki daCosta partly as a way of making sense of what had happened to her. “It was a cathartic thing,” she said over the phone. “There were times when I broke down, and she said alright, that’s enough, let’s stop, let’s have some tea, let’s have something to eat. It was going back, remembering stuff. I had to have a lot of counseling, for me to get rid of this anger, and bitterness; I felt I’d been treated badly, and discarded, and was useless.”

The two shopped the book around to publishers, but found little, or conditional, interest. “They said, Well, you’re not as famous as John. We’re not interested,” Beverley says. “‘Oh, there’s not enough juicy bits in it. You’ve got to lay it on.’” But she didn’t want her memoir to seem too bleak — “I wanted it to be a book where a woman gets herself together” — so she and daCosta decided to publish it themselves, which they did, two years after John Martyn passed away.

Sweet Honesty is written with the tone of a stranger’s confidence, and its existence feels important for both its author and the historical record, as well as by any concept of justice. Domestic violence wasn’t taken very seriously in the 1970s and ’80s; imagine the toll of abuse inflicted by someone who can do just about anything with impunity. (For more on this see Carol Ann Harris’s Storms: My Life with Lindsey Buckingham and Fleetwood Mac.) “There were often bruises on her arms,’ Faithfull writes of Anita Pallenberg, who was with Brian Jones in the mid-’60s. “No one ever said anything. What would there be to say? We all knew it was Brian.”

Beverley Martyn is still making music — her first album in over a decade, The Phoenix and the Turtle, was released in April 2014 — picking up a career that was tragically sidelined. (Joe Boyd, to whom John Martyn seemed “almost a cartoon villain,” says that “almost as depressing was how he squashed her music career.”) Her songs have a timeless, spectral feel, and her work, while significant on its own, is more haunting for having been buried under her husband’s yoke; the songs she’s singing now have all the weight of those years when no one was listening.

Music is more than music — it’s aura, character, culture, mythology, whatever speaks to you, which means the circumstances that inspire an album lie on a horizon of relevance. To know what Stormbringer! foreboded changes its feel, the same way Grace and Danger becomes a different album once you read Beverley Martyn’s version of the relationship it mourns. Beverley’s story is relevant to her work, and it’s relevant to her former husband’s.

Like the songs they discuss, each book evokes a sense of being there: not just on LSD at Brian Epstein’s, or floating in hash reveries on a bed with Mick Jagger, but young and in love. Pattie Boyd’s first few years with George Harrison seem all joy and light; when Boyd learned of his death, in 2001, “I burst into tears, I felt completely bereft. I couldn’t bear the thought of a world without George.” On tour with David Bowie in Japan, Angela watched a woman on a train feed their young son with chopsticks: “She smiled at us so tenderly that tears almost welled up in my eyes. When I saw David’s face shining with pride and love for his boy, they did. David could be so kind, so gentle; I loved him so much, I really did.”

While she was in Italy, Dylan wrote Rotolo gorgeous letters: “Don’t think I’m really loving movies — it’s just that I’m hating time — I’m trying to push it by — I’m trying to stab it — stomp on it — throw it on the ground and kick it — bend it and twist it with griting [sic] teeth and burning eyes — I hate it I love you.” Her recollections evoke the same feeling as the look on her face on the cover of Freewheelin’, as Dylan’s tone of voice on “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

At other moments, the books conjure the sickening thrill of obsession, the terror of knowing your lover is as brilliant as you think. Boyd, in the early stages of her “intoxicating, overpowering passion” for Eric Clapton, describes watching him from the side of the stage: “Amplifiers booming, lights up, music exploding in my head and vibrating through every part of me, was an incredible sensation — deeply sexy.” You don’t need to have dated a rock star to recognize that voluptuous, self-obliterating passion, or the compulsion, like the fumes of a Magic Marker, toward a power that’ll never be yours.

In most relationships, that power is the product of friction, and getting over a breakup involves the gradual realization that your ex’s marvelousness was partly your own invention. Here the subjective attraction is absolute, and so is the heartache, compounded by the public’s appraisal of your loss. The only thing for this kind of grief is to share it in common — to know that others have felt just as you do, and music offers that relief, although the pain manifest in a song might not be the singer’s — or to turn it into material. “I’ve made feeling work for me, through music, instead of destroying me,” Echols quotes Joplin. “It’s superfortunate.” To have a talent is “superfortunate” — an internal machine that can turn your desolation, or the desolation of those close to you, into comfort for strangers.

It’s a benevolent process, but a vampiric one as well. A central agony in these books is alienation — not only the pain of abuse, or heartbreak, or evaporation, but the pain of having your pain appropriated. The books themselves reclaim the hurt for their authors, and whatever their literary merit, they offer at least some catharsis for the reader, who can always relate. Rock songs make heartbreak seem valorous, but it’s more often a state of debasement in which you’d gnaw through the floor to get back what you had.

The books also serve as a caution, maybe a useless one, against letting passion erase us, against falling into the abyss. This resonates particularly with women, whose worth has forever been determined by the men they’re attached to, and whose place in rock and roll has been diminished and maligned. “In the end it doesn’t matter that hearts got broken and that we sweated blood,” Faithfull writes. “Maybe the best you can expect from a relationship that goes bad is to come out of it with a few good songs.” Or a book.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators