THIS: Bangs and Whimpers (2)

By:

August 14, 2017

One in an occasional series of essays considering the incendiary everyday lives and strangely drab dystopias of 1970s cinema.

In fin-de-everything 1970s America, even the future was nostalgic. The very idea of the “hero,” incorruptible, well-intentioned, could only be understood as a bygone dream in this rudely awakened decade. But it isn’t really we who decide where dreams come from or where they end.

The protagonist of They Might Be Giants (1971) — a crusading liberal judge driven by the disappointments of indifferent society and the crushing weight of widowhood into the delusion that he is Sherlock Holmes — explains his incongruous love of Hollywood Westerns as a way to witness a world of clear intentions and sincere self-sacrifice; a moral dependability which clearly belongs to a past as distant as his old self’s belief in fairness and justice, if either that world or that self ever even really existed. Another flawed lawman trying to do the right thing — the detective Thorn in Soylent Green (1973) — exists in a perpetual aftermath, surrounded by scrounged detritus of the 20th century and hearing every day about what pre-famine, pre-toxic life used to be like from an elder played by Edward G. Robinson, an actual icon of the 1930s and the films that mythologized them.

The run-down, sprawling New York City of 2022 in Soylent Green mirrored how most people felt about the city at the time, just magnified, while the fantasy life of “Holmes” in They Might Be Giants plays out in an enchanted metropolis that, while set in the then-present day, now feels as alien as Thorn’s sci-fi urban purgatory. Of course, like the bodies picked up not by hearses but garbage-trucks in Soylent Green, the kindness and panache that Holmes represents is being swept to the historical curb as we watch; the mental-patient’s misfit cohort hangs out in a decaying Times Square movie-house where he watches his Westerns, and all of them are eventually tossed out when the place abruptly converts to a porno grindhouse (a phase which, itself, is already a longstanding source of misplaced popular nostalgia as I write this).

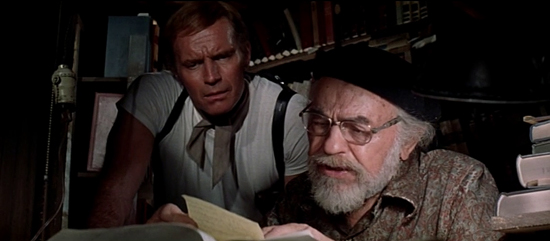

Holmes draws his therapist, who, by the kind of magical coincidence he’s always on the hunt for, is actually named Dr. (Mildred) Watson, along in the wake of his spirited, delusional pursuit of Professor Moriarty. Watson, like most of the outliers Holmes manages to befriend (including an all-night public-records archivist and a stifled civic-minded phone operator, each of whom slip him “evidence”), needs Holmes’ intense, illuminating form of belief, even if it means encouraging his hallucinations. Thorn relentlessly pursues the truth about environmental collapse and edible humanity in an unshakable faith that public knowledge will make a difference; arguably a more self-destructive fantasy than Holmes’.

The make-believe locales of They Might Be Giants remain more redeeming than the cautionary ones of Soylent Green, though they are equally prescient — Holmes and Watson discover a rooftop garden grown by a couple who have survived off this self-established eden and not set foot outside since the Great Depression started; this anticipates the green urbanism of our current decade, while the spacey upscale apartment-complex an assassin accesses by way of a long concrete canal to kill Joseph Cotten in Soylent Green bears an eerie similarity to the buildings that have been going up this decade around real-life NYC’s High Line Park (formerly an abandoned elevated rail-line), and, it becomes evident, is situated in the same part of town.

The castles in They Might Be Giants all remain charming, from the Romanesque armory and minareted post-office buildings that still stand in Greenwich Village, to the playfully shadowy labyrinths Holmes and Watson repeatedly find themselves in. Those shadows provide the shelter when it’s not actual night out, as it is a lot in both movies. At one point Holmes and Watson emerge from an underground tunnel across from that once-upon-a-time oddity of the pre-24-hour world, an all-night supermarket; inside they find valleys of abundance that Thorn could only dream of, under the heavenly fluorescent glare, while a solitary manager serenades the empty store with master-thespian renditions of the latest specials. The store’s long horizontal glass-box exterior looks unsettlingly similar to that of the icy, anodyne euthanasia clinic Robinson’s character trudges to through an equally vacant nighttime city in Soylent Green.

I’ve kept calling They Might Be Giants’ character “Holmes” because the name of his former self, “Justin Playfair,” sounds even more made up. While Soylent Green slams down on a note of certain decline, They Might Be Giants fades out in an air of ambiguity over who our “real” selves are and whether we’re mortal at all as long as we create our story. Holmes and Watson’s adventure may be a dream that never has to end, or maybe, as Thorn’s stretcher is carried out of the bloody church, we’re seeing that the courageous ideas of the 20th century have died in their sleep.

For an alternate take on Soylent Green, keep reading HILOBROW’S KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE