STUFFED (26)

By:

August 11, 2017

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (British Library Publishing, October 2016; Overlook Press, March 2017). STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

Venison has always been eaten in Great Britain, but even as far back as the Norman conquest (when William the conqueror set aside vast areas as a royal hunting ground) regular folk had to poach or steal from the aristocracy to get a taste. The Inclosure Acts since then, especially those at the beginning of the 17th century, made the association of deer and royalty so tight that possessing venison without proper provenance could get you strung up by the Sheriff of Nottingham’s spiritual descendants. As a result, venison recipes in English cookbooks and contemporary accounts have a very particular character, different from all other foodstuffs.

When Samuel Pepys’ diary says (July, 1660):

Thence to my Lord about business; and being in talk, in comes one with half a Bucke from Hinchingbrooke, and it smelling a little strong, my Lord did give it to me, though it was as good as any could be. I did carry it to my mother to dispose of as she pleased.

To our modern ear it’s a weird anecdote. Why would his Lord (Pepys’ patron Edward Montague) give Pepys a slightly spoiled deer?

In fact, there are a variety of well-disseminated recipes for dealing with tainted venison in 17th-century cookbooks, and these stories and recipes are probably what gave rise to the notion that the English were routinely eating spoiled meat and that their use of strong spices was meant to bury this bad flavor. The spices and venison did go together, just not quite like that: they were both the food of the wealthy and meant to signal an aristocrat’s station; giving someone below you on the class ladder an edible but slightly funky deer would have been seen as an appropriate kindness, a thoughtful gift — thus, why Pepys immediately re-gifted the funky deer to his mother, to spread the social climbing wealth.

Pepys’ mother would likely have used a recipe like this one to recover the meat (from The Accomplished Ladies Rich Closet of Rarities, 1687):

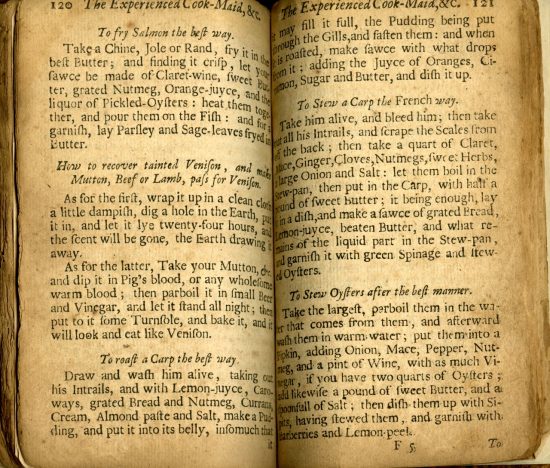

How to recover tainted venison, and make mutton, beef or lamb, pass for venison:

As for the first, wrap it in a clean cloth a little dampish, dig a hole in the Earth, put it in, and let it lye twenty-four hours, and the scent will be gone, the Earth drawing it away.

As for the latter, take your Mutton & dip in in Pig’s blood, or any wholesome warm blood; then parboil it in small Beer and Vinegar, and let it stand all night; then put to it some Turnsole, and bake it, and it will look and eat like Venison.

* Small beer is a light, very slightly alcoholic beer or ale; turnsole can refer to a few different plants, but here it is a purple dye.

The spread of these instructions for resurrecting turned venison (they appeared in Hannah Wooley’s popular 17th-century cookbooks and proliferated in the 18th century) suggest that there was a fair amount of venison being passed down the social ladder. If you had you own deer park (as the reserves where deer were kept by the wealthy for food and sport were called; Pepys’ Lord Montague had a deer park at Hinchingbrooke) you’d hardly need to be bending over backwards to bury and exhume your spoiling venison. You’d usually leave it buried and shoot another. No, these instructions were often meant for folks like Pepys, members of the emerging middle class who wanted to impress their peers and feel just a little closer to the aristocracy that loomed over them — so a parallel economy in modestly rancid deer meat sprang up.

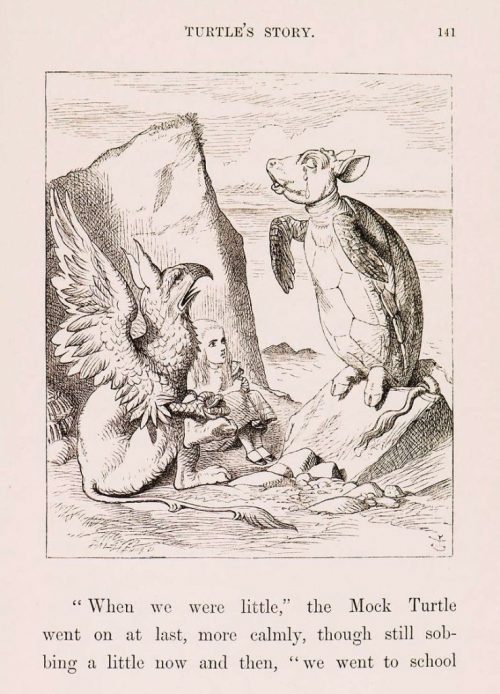

The second part of the recipe speaks to this even more directly. We’ve all heard of mock turtle soup which became popular in the 18th century because the proper turtles were hard and expensive to procure, but mock venison was the original aspirational British dish.

This mock venison is made by dipping mutton in pig’s blood, parboiling in small beer or vinegar, staining with turnsole and baking. Like with the idea of drawing out the bad flavor of your rapidly spoiling venison by burying it in the ground overnight in a clean cloth, there is something undeniably alchemical about transmogrifying mutton into venison by this process. Class boundaries in England must have often seemed as if they could only be rendered permeable through such a quasi-mystical practice, as if hard work, urgent desire, plus something weird might just give you the key to unlocking the peerage.

Pepys was also a devotee of the venison pasty, likewise supplied by Lord Montague, so he was aware when he was served a fraud (entry from January 6, 1660):

From thence I went to my office, where we paid money to the soldiers till one o’clock, at which time we made an end, and I went home and took my wife and went to my cosen, Thomas Pepys, and found them just sat down to dinner, which was very good; only the venison pasty was palpable beef, which was not handsome.

Etymological aside: The word venison comes to us from Latin, venari, “to hunt” and before that from Proto-Indo-European wen, “to strive for.”

As cookbooks began to be published in the United States, recipes for mock venison appeared. In 1860, the American Lady’s System of Cookery had a recipe for turning a whole sheep into a whole mock venison and other recipes frequently appeared during the 19th century. This despite the obvious fact that deer were in no way the purview of the wealthy in the United States — where they were numerous and more or less free for the taking. But an appetite for mock venison existed because the association with royalty (from tales of Robin Hood poaching in Sherwood Forest to English immigrant stories and memories) was so strong that even with every bit of reality aligned against it, that venison still seemed rich.

Why venison never quite took off in the US is a complicated question, but a big part of it is how the USDA inspects exotic meats (and Walt Disney’s Bambi didn’t help). It’s a different process, costs extra, and is sufficiently difficult that you just don’t see deer meat in restaurants and supermarkets much. In the UK, recent beef scares have led venison to make a comeback, so, ironically, it’s currently much easier and cheaper to eat venison in England than in the US. Here it’s still hunters and hipsters who eat most of the venison. I say bring back the mock venison — maybe we can export it back to England if it catches on.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.