THIS: Time Sensitive

By:

July 24, 2017

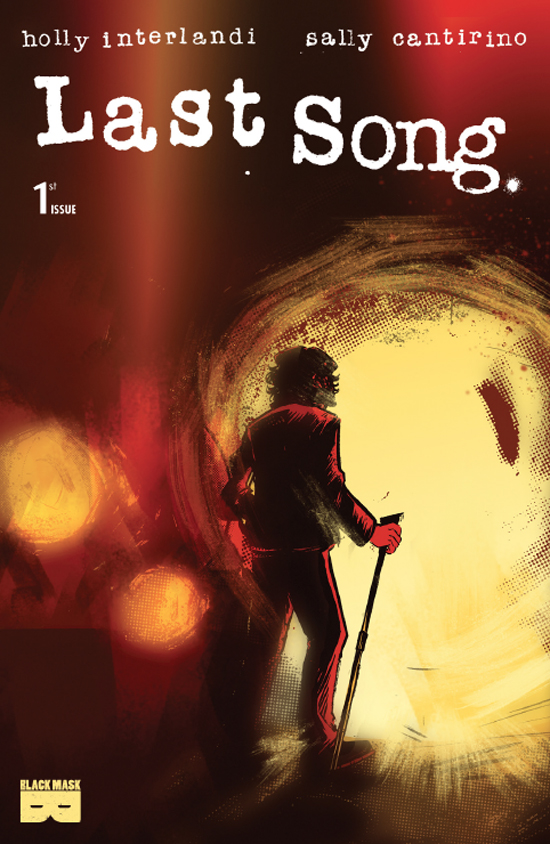

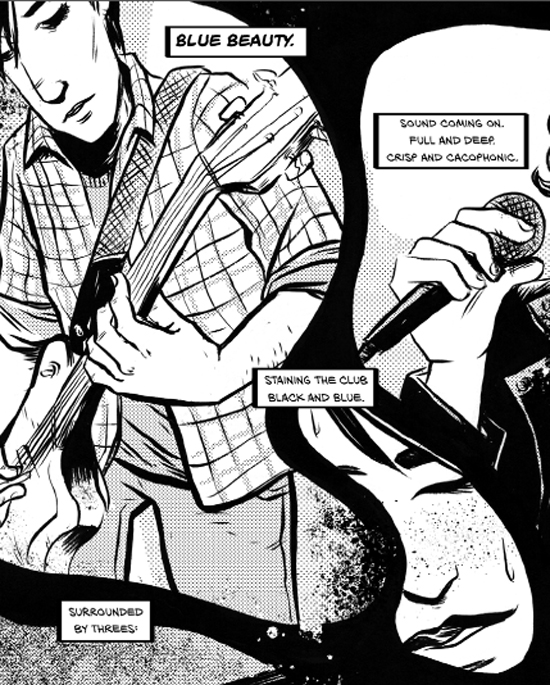

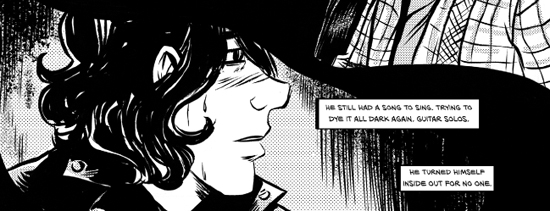

We can’t change the past, but it does keep happening again. Relived experience is at the heart of Last Song, a serialized graphic novel by writer Holly Interlandi and artist Sally Cantirino. Everyone’s youth is forever ago, and this drama of a fledgling punk band of unfinished personalities makes its mostly-1980s milieu feel like ancient history that we all, in one way or another, find familiar.

Last Song is like a quest to recover someone else’s memory; Interlandi projects her own youthful mental turmoil and creative drama onto the rise and fall (and troubled upbringing and ambivalent maturity) of a few drifty yet visionary LA kids (some from Cincinnati). Songwriter Nicky (his dad dead of suicide early on) needs to be noticed; best friend Drey needs to be needed by Nicky; bassist and drummer Charlie and Alex want to continue seeming to need nobody, in the company of this tight surrogate family. Interlandi’s structure circles the sequential life story like the traumas and doubts and voids the characters dance around, and Cantirino’s imagery provides the unique faceting of incident that the comics artform allows, to come at the narrative from multiple directions with some richly missing pieces.

The first issue’s scenes jump from Nicky’s late-1970s childhood to an as-yet only glimpsed late-1990s post-life, with years of the early-to-mid-’80s circulating out of order in-between; Interlandi understands the fragmentary, slow-acting nature of memory, and comics lets her assemble this story (originally envisioned as a prose novel) like a time-lapse collage. The characters’ internal narratives slide into each other, and at times an ambient extra-reality overtakes all else, when the band’s creations are coming together and the dreamlife they strive for is expressed collectively in the lyrical, illusory language best suited to shape it. Cantirino’s sure, sketchy style is like cartoons scrawled on dive-bar walls, telling its own, intertwined story in pure attitude and shadowed feeling.

The high planes the band tries to reach are all the struggle and wonder this narrative needs, making it the truest portrait of the musical-yet-unsung life I’ve yet read in comics, and one of the best observed and interpreted in any media. Masterworks like Gillen & McKelvie’s Phonogram or The Wicked + The Divine are fantasias that embody the essence of music; many other comics and animated shows use a rock ’n’ roll existence as the scaffold for stories of satanic deals, spy-craft and outer-space adventures; and movies like David Chase’s Not Fade Away are perceptive studies of human behavior in a band context. But Last Song is possibly the best work (and definitely the best comic) about the inner lives of musicians themselves, their singular expectations and uncertainties, ever done. This is not a “backstage musical,” but a journey to the back of its characters’ and readers’ minds.

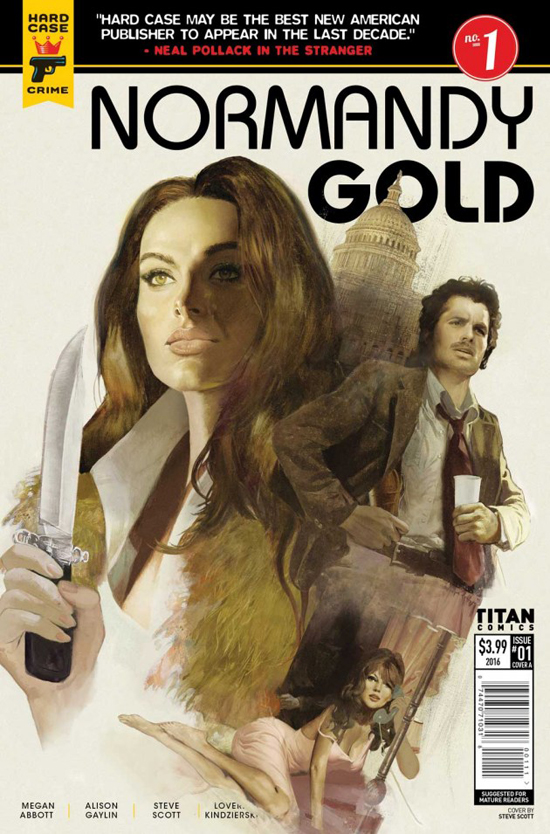

The past stays the same, except when it’s told differently. Runaways and the bad ends (or not-even-acknowledged disappearances) they came to were a staple of 1970s sensationalist journalism and exploitation issues-pop, from network-TV movies like Born Innocent to “Partners in Crime,” the title track from the same album that gave us “The Piña Colada Song.” Equally omnipresent were borderline-porn crime dramas of flawed, determined private eyes (and I do mean, usually, dicks) — the runaway as protagonist, and the thriller told from the perspective of embattled female experience rather than slapped together from a basis of rape-as-plot-device, were more or less unheard of. Normandy Gold, from the comics branch of Hard Case Crime, gives us both, set in the ’70s to set the canon straight. Named for the WWII battle, from which her dad did not return, Normandy Gold is a troubled runaway turned at-risk junior survivalist, ward of a local lawman, and eventually badass sheriff of a remote Oregon town herself. She has had to emerge from the wilderness to follow the trail of her estranged, now missing sister, whose path led her to prostitution near the halls of power in Washington, DC. Writers Megan Abbot and Alison Gaylin have a clear, long memory for the period’s rural/urban antagonisms (ancestor of today’s red-state/blue-state divide and cartooned in metro-cowboy copshows like McCloud at the time), and for the overall shiny squalor of this era in which the tides of liberation and exploitation regularly collided.

Artist Steve Scott gets the decade more right than any of his visual peers in a recently-burgeoning field, and seems to be channeling a different ’70s comic style in each of the two issues so far — first Gene Colan and then Paul Gulacy, with the shadowy drama and hi-res lechery those respectively suggest. It’s fair game; Abbot and Gaylin, like their counterparts Alex de Campi and Ed Brubaker, don’t shrink from the conventions of the genre, and undercover in the “oldest profession” Normandy spends as much time out of uniform as Pam Grier would; in the same way that her sister and she are like alternate versions of the same life, one victim and one victor, Normandy herself is fighting her way out of a stereotype so strong it can change the present. Though if she survives this series, I’d love to read a sequel “Normandy Silver” story set in the 2010s where we see how she kicks ass in her seventies.

Intense critical attention, widespread cultural impact and a horde of Emmy nominations have made The Handmaid’s Tale’s future current again. I had wished this form of tyranny to be an artifact of the 1980s “Moral Majority” environment that inspired it (though the gladiatorial, corporate raw meanness of Kelly Sue DeConnick & Valentine De Landro’s Bitch Planet was seeming sadly just right). With a Puritan patriarch second in command of the country and all of his beliefs being actively pursued, Margaret Atwood’s vision again seemed as clear as it did during the sanctimonious era of its origin. The original novel remains the only lyrical dystopia I know of, so a certain amount of coarsening in its transfer to a less interior medium (stage, film, TV) is not only inevitable, but maybe necessary — the brutality has to be un-abstracted, so long as it isn’t materialized to the point that it becomes lurid (see: Jonathan Demme’s B-movie butchery of Beloved). The crass 1990 Handmaid’s Tale movie is history neither forgotten nor repeated in the Hulu series. The grinding pressure of a totalitarianism that reaches into your body and mind is well portrayed, and Elisabeth Moss’ face conveys the spectrum of horror with eloquence, while her voiceovers do not intrude, but rather feel like a distress so profound it spills beyond her mind and seeks expression in the silent air.

Most of the compressions (i.e., folding Offred’s mom into Moira) are thematically sound, and while I worried that the diversifying of the cast might not ring true with (and thus euphemize) the white supremacy of the novel’s world, in the years since we have gotten a racist regime that’s at least superficially secular, while some of my own Evangelical relatives are in multiracial families and congregations bonded around the same doctrine, and this is not uncommon. (The banishment of characters of color from some of the Reagan/Bush era’s most signature political dramas — see: Longtime Companion — and demotion of their real-life counterparts within their own narratives to focus on white saviors — Mississippi Burning, etc. — would leave The Handmaid’s Tale itself too far in the past, while it unfortunately belongs right here.)

The idea of sanctuary in Canada is also more achievable and less morally random than the novel emphasized, but the expanded conception of relations between Gilead and Mexico (one thing I won’t spoiler in this piece) is counterbalancingly hopeless enough for anyone. (And the scenario of former Americans cast into the position of rootless refugees was a symbol for the current decade that may well have been wise not to resist.) The internet and its potential for insurgency and abuse were effectively nonexistent when the book came out, and the evolving of the story to account for this, as well as moving the timeline up to reflect the personal politics of male/female relationships and the greater self-determination of women circa 2017 rather than 1985 (the Commander’s queasy dominance of Offred in their “affair”; the shift of Serena from televangelist to movement mastermind) are all sound extrapolations. In these ways The Handmaid’s Tale seems to lend itself to serving as a living text in counterpoint to the ways that books like 1984 are more fixed touchstones, immutable warnings while not eternally relevant in all ways. In her own cautionary prophecy, Atwood may have had the singularly strategic imagination to create a franchiseable end of the world. You can’t change the future, but it happens a different way each time.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE