10 Best Adventures of 1952

By:

July 13, 2017

Sixty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Forties (1944–1953) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any 1952 adventures that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Frederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Space Merchants (serialized, as Gravy Planet, 1952; in book form, 1953). Because I’m a science fiction fan who works in the esoteric outer reaches of consumer research (semiotic brand analysis), people occasionally wonder whether I was somehow deeply influenced by The Space Merchants, at an impressionable age. Not so. But I do like this proto-Idiocracy, cyberpunk-ish dystopian adventure, in which ace copywriter Mitch Courtenay, whose agency has just landed the plum assignment of persuading inhabitants of the overcrowded and exhausted Earth to voluntarily emigrate to new colonies on Venus, is kidnapped by rebels who want him to articulate their movement’s “functional and emotional benefits” (as marketers put it) instead. Huge, amoral and trans-national corporations have taken the place of governments, in Pohl and Kornbluth’s story, and advertising has become the vehicle by which the masses are deluded into consuming more, more, more. Venus, meanwhile, is a hellhole — it will take generations before colonists can live there in anything but harsh conditions. What will Courtenay do? Fun fact: Originally published in Galaxy (June–August 1952) as a serial (with a better title: Gravy Planet), The Space Merchants helped introduce such marketing and sci-fi neologisms as “R&D,” “Muzak,” and “soyburger.” In 1960, Kingsley Amis suggested that The Space Merchants “has many claims to being the best science-fiction novel so far.”

- Bernard Wolfe’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Limbo (1952; in the UK: Limbo ’90). Limbo is: a tedious, aggravating work of genius; a post-apocalyptic antiwar treatise that is skeptical of pacifism; and a serious novel of ideas written by an inveterate punster. In 1990, after the cataclysm of WWIII has wiped out Paris, London, Rome, and other cities, the diary of a disillusioned brain surgeon is discovered. Dr. Martine’s irreverent, sarcastic notions — e.g., disarmament taken to a literal, amputational extreme — wind up providing an ideological basis for an absurdist worldwide movement. The disarmament movement has split into two factions: one remains helpless (paraded in baby carriages by their wives or mothers); the other replaces the missing limbs with powerful artificial ones. Martine’s peaceful Indian Ocean island home is invaded by cyborgs from the latter movement, who seek a rare metal — one thinks of “vibranium” — to power their limbs. He seeks to preserve the island… but he’s not a sympathetic character, as his lobotomization practice and misogynistic stream-of-consciousness fantasies demonstrate. Fun fact: Limbo is considered one of the first novels about cybernetics, and it’s been described as a precursor of both the New Wave and Cyberpunk sci-fi movements. J.G. Ballard called Limbo “one of the books that encouraged me to write SF.”

- Hammond Innes’s Robinsonade/frontier adventure Campbell’s Kingdom. This is one of Innes’s better adventures; perhaps I enjoy it so much because it is particularly Buchan-esque. Like Buchan’s 1941 yarn Sick Heart River, Campbell’s Kingdom concerns a British man who — having been diagnosed with a terminal illness and given a year to live — lights out for the Canadian northwest, seeking meaningful work and a place where he feels that he truly belongs. Bruce Wetheral, dying of cancer, inherits his grandfather’s land in the Canadian Rockies. His grandfather believed there were vast oil reserves there; the oil was never discovered, and the family’s name was disgraced. Was he a con man? Declining an offer for the land — which will be flooded once a proposed dam is constructed — Wetheral makes his way to “Campbell’s Kingdom” and decides to drill for oil. There’s action, romance, harsh weather, and guerrilla tactics agalore; Innes’s research into the drilling business lends verisimilitude. Fun fact: The novel was a bestseller. It was adopted as a forgettable 1957 British adventure film starring Dirk Bogarde.

- Theodore Sturgeon’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure More Than Human (1952; as a book, 1953). In this far-out updating of Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John, a Radium Age-era Argonaut Folly, tortured mutants with amazing talents — Lone (“the Idiot”) can read and control thoughts; eight-year-old Janie can move objects with her mind; Bonnie and Beanie can teleport; Baby is a super-genius; Gerry is a sociopathic urchin able to bind the others into a unified “gestalt” — threaten the prolonged existence of humankind as we know it. In the final section of the book, Lt. Barrows, a gifted engineer who worked for the US Air Force until he apparently went insane, discovers that he was a victim of the gestalt — who wanted to prevent him from discovering the secret of their antigrav device, not to mention their very existence. Will Hip fight back against the mutants… or join them? Fun fact: More Than Human is a “fix-up” of Sturgeon’s previously published novella Baby is Three; two new sections were written for this version.

- Jim Thompson‘s crime adventure The Killer Inside Me. In the mid-1980s, when I was in college, Black Lizard Books reprinted several Jim Thompson novels, including this one, and the obscure pulp writer was suddenly hip. (Sean Penn called The Killer Inside Me “the best book I’ve ever read.”) Lou Ford, the psychopathic deputy sheriff and this novel’s narrator, is an amazing character. He appears to be a typical small-town police officer, amiable and boring; in fact, he’s a depraved sociopath, a sexual sadist, and a murderer. As he cheats on his girlfriend, abuses a prostitute, blackmails a rich man, murders, and and frames others for his crimes, do we root for Lou or not? Its a tough one. Fun fact: Adapted as a movie twice, with Stacy Keach and Casey Affleck playing Lou Ford, but neither time very well. Stanley Kubrick called The Killer Inside Me “probably the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered.” High praise!

- Alfred Bester’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure The Demolished Man (serialized 1952; as a book, 1953). A cartoonish but far-out police procedural — one in which we immediately learn who the murderer is. In the year 2301, telepathic police operatives (“Espers,” or “peepers”) have made premeditated murder impossible; there hasn’t been one in decades… until Ben Reich, a megalomaniac industrialist, decides to murder his business rival, D’Courtney. He enlists the support of a renegade Esper, who not only assists with the plotting and execution of the murder, but teaches Reich a maddening jingle — an earworm — that will prevent anyone from prying into his mind. Enter Lincoln Powell, Esper and police prefect, who uses his network of peepers to help him obtain evidence, while racing to find D’Courtney’s daughter, an eyewitness to the murder, before Reich does. There’s plenty of action and high-tech gadgetry — including flash grenades that destroy the retinas of on-lookers, and “harmonic” guns. If Reich is caught, he’ll be subject to “demolition,” in which the offender’s personality and memories are extracted…. Fun fact: Winner of the first Hugo Award. In 1959, Thomas Pynchon applied for a Ford Foundation Fellowship, proposing to adapt The Demolished Man as an opera. His application was denied.

- Kurt Vonnegut’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Player Piano (1952). During WWIII, while the American (male) workforce was fighting overseas, out of necessity American engineers made tremendous strides in automating most manual labor. Today (in the near future), most Americans are either busy and fulfilled engineers and managers, on the one hand, or discontented idlers, on the other. Paul Proteus, successful and contented manager of the automated Ilium Works, is the son of one of the men who created this new economic and social order; although he’s inherited his father’s reputation, he harbors secret doubts. An anthropologist and Episcopalian minister, Reverend Lasher, persuades Paul that life without meaningful work is boring and inhuman; Paul begins to fantasize about quitting his job and living off the grid. During a retreat for elite engineers, Paul quits his job — at which point Lasher’s secret organization begins to use him as a messianic figurehead for their anti-technology revolution. What will transpire when the revolution begins? Fun fact: Vonnegut’s first novel was inspired by Brave New World, as well as by his own postwar experience working at General Electric. At the time, he didn’t want it classified as “science fiction.”

- C.S. Lewis’s Narnia sea-going adventure Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Writing about David Lindsay’s Radium Age sci-fi novel A Voyage to Arcturus, C.S. Lewis enthused: “To construct plausible and moving ‘other worlds’ you must draw on the only real ‘other world’ we know, that of the spirit.” Lewis’s Perelandra sci-fi trilogy uses planets in this Linday-esque manner… while Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the third published Chronicles of Narnia installment, uses islands in a similar fashion. Edmund and Lucy Pevensie, and their odious cousin Eustace Scrubb (who will remind readers of Kipling’s Captains Courageous of the odious Harvey Cheyne Jr.), sail with Prince Caspian (titular protagonist of the previous book) on the Dawn Treader in search of the seven lost Lords of Narnia. Each island they explore provides a test of the explorers’ intrinsic characters; the most memorable island, for this reader, is the one with the dragon’s hoard. Some Narnia fans complain that this is the least compelling installment, contra to which I offer one word: Reepicheep!

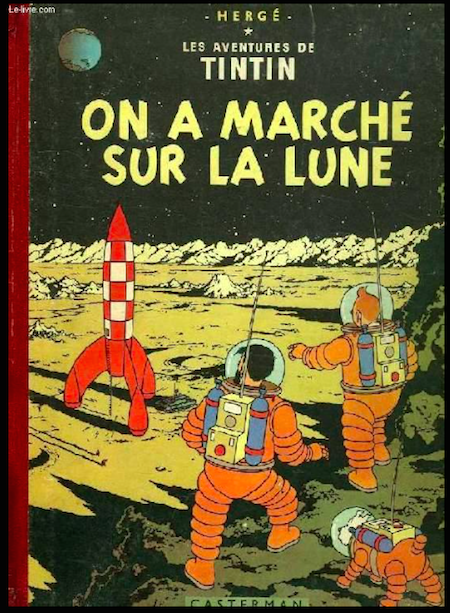

- Hergé‘s Golden Age sci-fi Tintin adventure On a marché sur la Lune (Explorers on the Moon). The seventeenth Tintin yarn sees our heroes landing on and exploring Earth’s moon — seven years before the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 mission, and seventeen years before the United States’ Apollo 11 was the first manned mission to land on the Moon. Professor Calculus, here, is no longer a brilliant bumbler — but the guiding spirit of the expedition; his assistant, Wolff, is a flawed, Le Carré-esque character. Thompson and Thompson and Haddock nearly ruin the mission, but the rocket eventually lands safely and Tintin becomes the first explorer on the Moon. Although the plot is a bit pedagogical, the landscape is eerie and amazing. Meanwhile, it turns out that a spy for a foreign power is aboard — will he hijack the rocket? Fun facts: This is the sequel to Destination Moon. It was serialized weekly in Belgium’s Tintin magazine in 1952–1953; published in book form in 1954. It has been suggested that Hergé was motivated to do a sci-fi story by the success of his colleague Edgar P. Jacobs’s first Blake and Mortimer comic, The Secret of the Swordfish (1950–53).

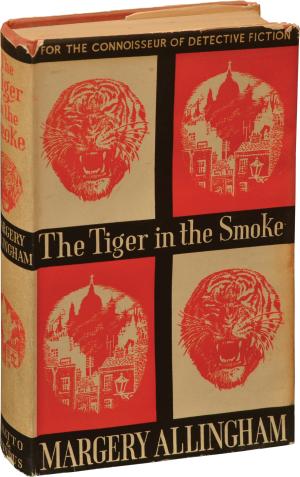

- Margery Allingham‘s crime adventure The Tiger in the Smoke. The fourteenth Albert Campion novel is an atmospheric thriller about a serial killer — escaped prisoner “Jack Havoc” — who’s on the loose in London. It’s also a hunted-man adventure (Campion, an amateur sleuth, aided as always by his ex-burglar manservant Lugg, seeks Havoc) and a treasure hunt (Havoc seeks a buried treasure he learned about during the war; so do his his wartime compatriots). When her fiancé is kidnapped, Meg Elginbrodde (whose deceased ex-husband may have been involved in the treasure escapade) enlists Campion’s help. With Cockney police detective Inspector Luke, Campion hunts the vicious beast at loose in “the smoke” (period slang for London). A thick fog settles over the city; the plot develops gradually; and the characters — particularly the Lafcadio-esque Havoc, a believer in “the science of luck,” and the street gang of ex-servicemen — are fascinating. Fun fact: Though not necessarily Allingham’s most amusing novel, The Tiger in the Smoke is considered one of her finest. It is J. K. Rowling’s favorite crime novel.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.