INTO THE GROVE (16)

By:

June 10, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

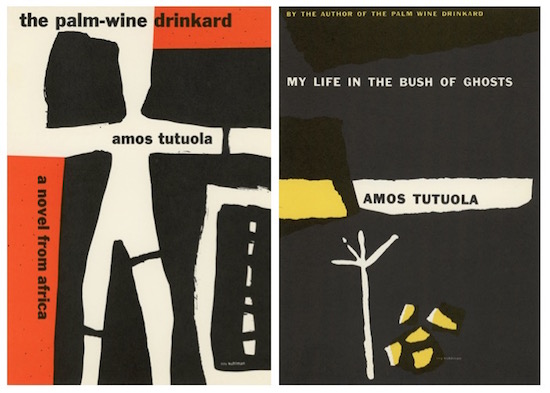

Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard (1952, 1953)

Amos Tutuola’s My Life In the Bush of Ghosts (1954), introduction by Geoffrey Parinder

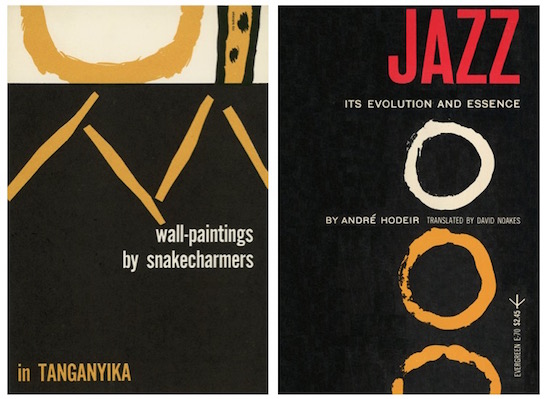

Hans Cory’s Wall-Paintings by Snake Charmers in Tanganyika (1953)

André Hodeir’s Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence (1956), translated by David Noakes

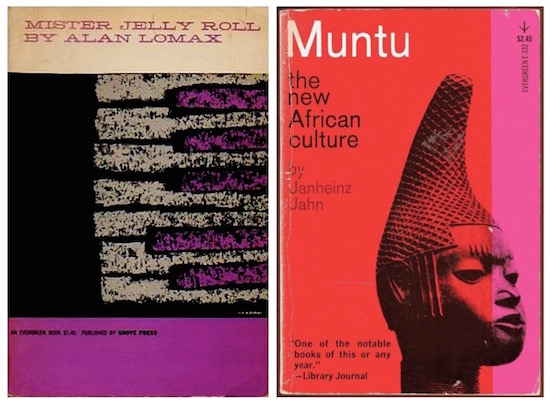

Alan Lomax’s Mr. Jelly Roll (1950, 1956)

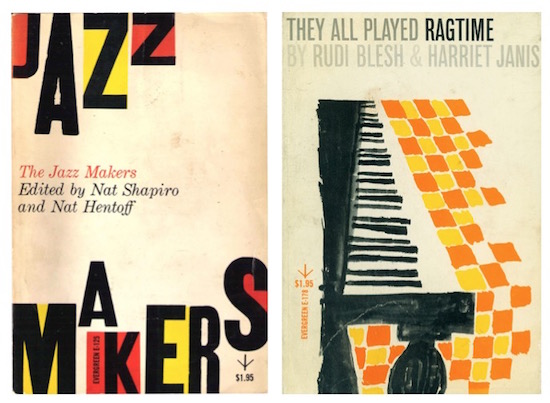

The Jazz Makers (1957), Nat Hentoff & Nat Shapiro editors

Rudi Blesh & Harriet Janis’ They All Played Ragtime (1950, 1959)

Jarlhein Jahn’s Muntu: The New African Culture (1958, 1961)

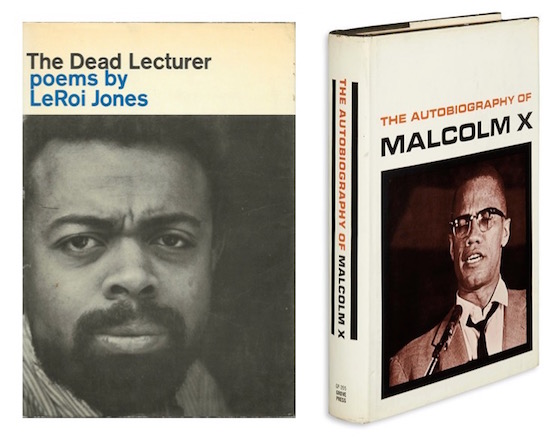

LeRoi Jones’ The Dead Lecturer: Poems (1964)

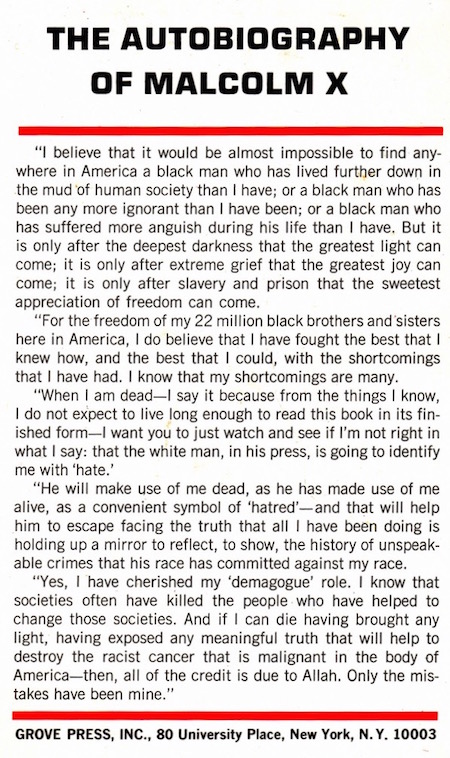

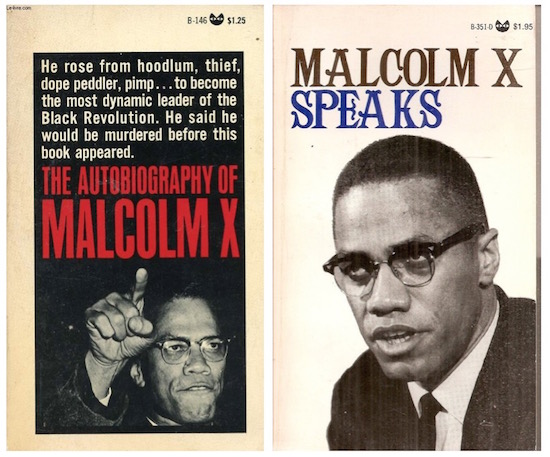

The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), introduction by M.S. Handler, epilogue by Alex Haley

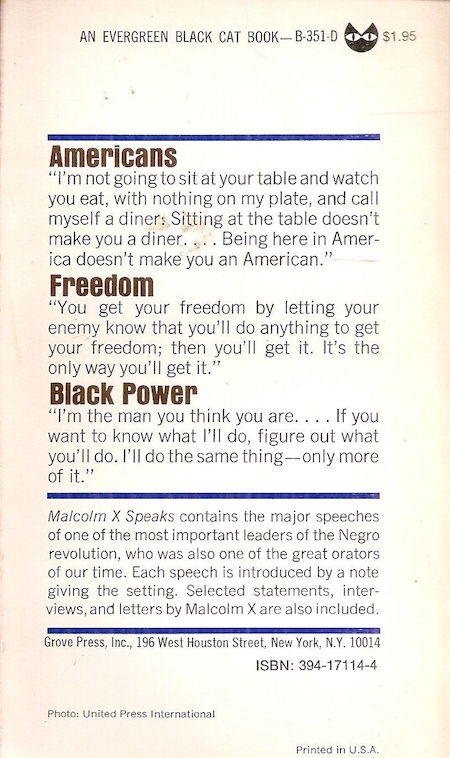

Malcolm X Speaks edited by George Breitman (1966)

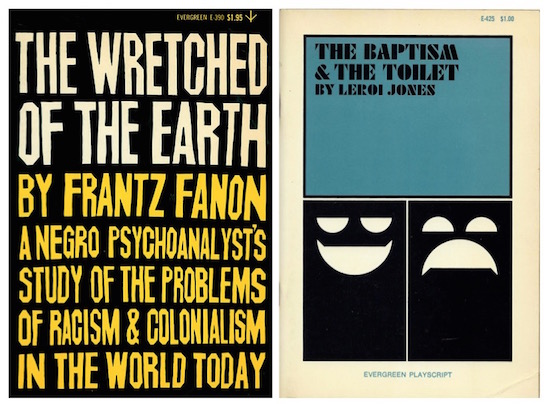

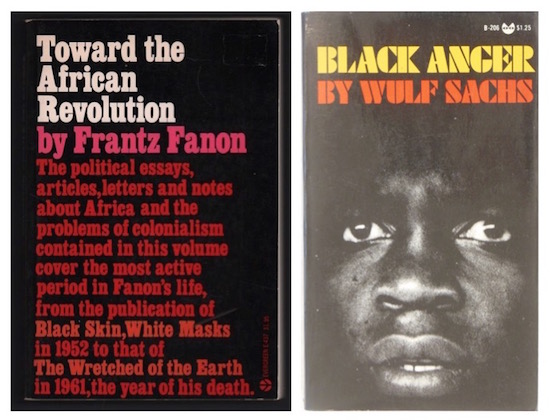

Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth (1961, 1966), translated by Constance Farrington

LeRoi Jones’ The Baptism & The Toilet (1966)

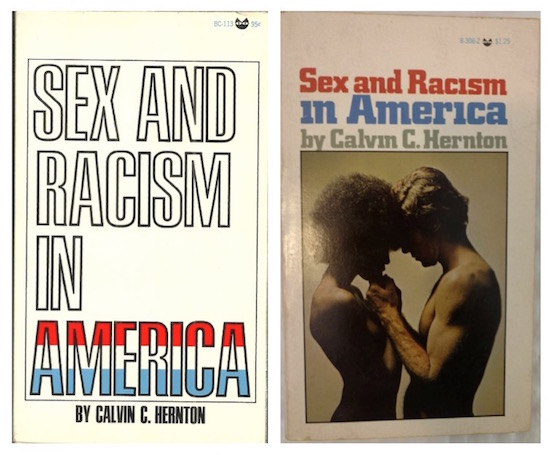

Calvin C. Hernton’s Sex and Racism in America (1966)

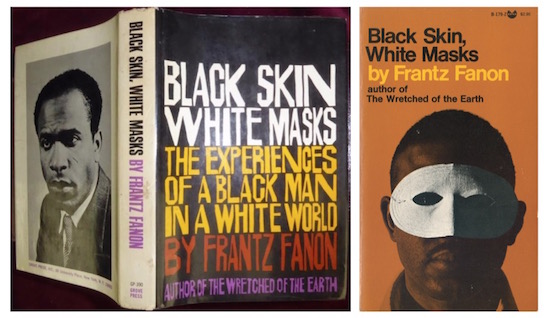

Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952, 1967), translated by Charles Lam Markmann

Frantz Fanon’s Toward the African Revolution (1967), translated by Haakon Chevalier

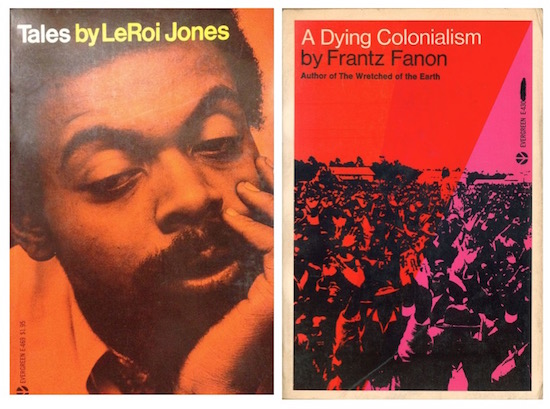

LeRoi Jones’ Tales (1967)

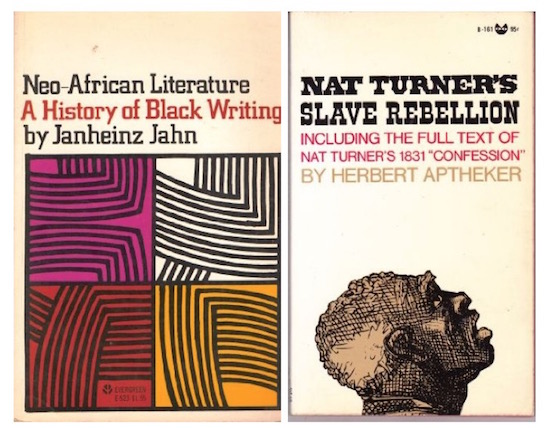

Herbert Aptheker’s Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1968)

Frantz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism (1959, 1969), translated by Haakon Chevalier

Jarlhein Jahn’s Neo-African Writing (1969) translated by Oliver Coburn and Ursula Lehrburger

Wulf Sachs’ Black Anger (1947, 1969)

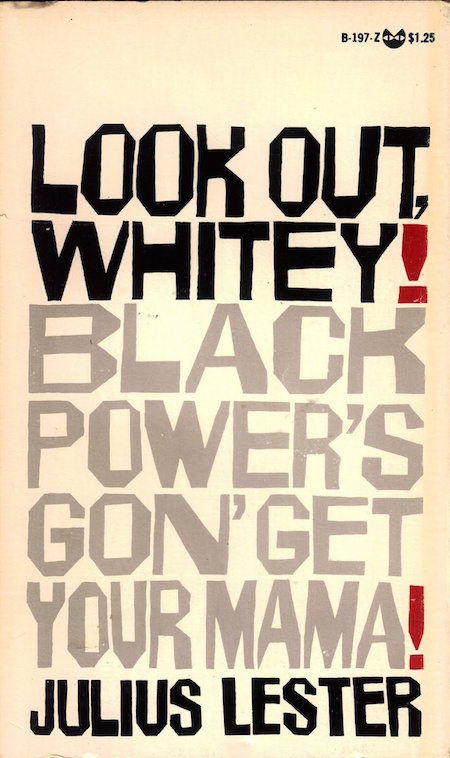

Julius Lester’s Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama! (1969)

All cover designs by Roy Kuhlman

As one proceeds through the Grove Press catalog of the 1950s and early 1960s, questions of race — as everywhere in America— are both unavoidable and vexing. Despite Barney Rosset’s proven devotion to Civil Rights (see Into The Grove #11) it can seem that Grove published fewer black authors than might be expected. Perhaps, but there are a number of factors to consider beyond mere numbers.

First, and most crucially to many writers, is financial. Grove paid very small advances to everyone, including now canonic authors like Samuel Beckett and William S. Burroughs; any author who could be successfully published elsewhere, almost certainly would for the simple reason that $3000 (say) is more than $300. The only reason Grove got to publish Malcolm X is because Doubleday cancelled its publication following Malcolm’s February 21 1965 assassination. On the literary front, when Grove signed Newark, New Jersey-native LeRoi Jones — a uniquely brilliant artist comparable in ability to any of its other avant-garde writers — it’s telling that his excellent but relatively conventional books of music criticism cum social history, Blues People (1964) and Black Music (1967) were published by a mainstream house, William Morrow, with little use for his poetry, fiction or theater works. It’s worth noting also that Grove’s list of books on black subjects by non-black authors was substantial; if there are omissions, how could there not be? There were dozens upon dozens of publishers large and small, trade and academic also in the racket, and with whom they competed; nobody could do it all.

Could they have been better? Sure but with Amos Tutuola of Nigeria, Frantz Fanon from Martinique, Malcolm as the former “Detroit Red”; Tennessee-raised New York sociologist and poet Calvin C. Hernton and another Tennessean, the radical folksinger turned lyrically inclined polemicist Julius Lester all in house, Grove did pretty well by strong black voices.

To my mind, Grove Press’s one signal failure was one it shared with nearly all other publishers and critics: the revival of the crucially important black writer Charles W. Chesnutt (1858–1932). In an era when Grove was exploiting the public domain to great effect, with such racially charged and conflicted works as Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man, George Washington Harris’s Sut Lovingood stories, and Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson (see Into The Grove #6), Chesnutt’s immense achievements of 1890s and early 1900s — novels, stories, essays, a Frederick Douglass biography — remained forsaken. Though he’d been championed by Williams Dean Howells in his lifetime, only once, in 1937, when Houghton, Mifflin returned 1899’s The Conjure Woman to print was a significant Chesnutt revival even suggested until the 1960s. That there exist generations of Faulkner scholars, for example, who opine on “race” knowing almost nothing of Chesnutt is as damning indictment of (ofay) “consensus” as any in American literature. Even a great critic and Faulkner anthologist like Malcolm Cowley wrote nothing of Chesnutt; Edmund Wilson, likewise, not even in Patriotic Gore; Lionel Trilling? Please. Young and old Alfred Kazin alike ignored — or was ignorant of — Chesnutt. What’s his problem? In 1967, when Chesnutt was included in the Langston Hughes-edited anthology The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers, 1899-1967, the book was published by Little, Brown, presumably because that’s where the money was.

Interviewed after the publication of his stunning debut novel, The Free-Lance Pallbearers (1967) which some critics compared to the satires of Burroughs (see Into The Grove #1), Ishmael Reed demurred. “My book has more in common with Charles Chesnutt. The critics can’t get to that because they’ve never read an Afro-American novel written before those Jewish books that James Baldwin wrote, that Sol Yurick could have written, that Malamud could have written, that Saul Bellow could have written, that Norman Mailer could have written.”

Had Grove Press published Charles Chesnutt a decade or more earlier — as it could have, for free — perhaps Reed wouldn’t have been so misunderstood. Questing it was, however, Grove couldn’t always be that much better than the oppressions and prejudices of the society it was born from.

NB: Published in 2002, the Library of America volume, Charles Chesnutt: Stories, Novels and Essays, edited by Werner Sollors, is an essential and revelatory corrective to a century of undue neglect.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.