INTO THE GROVE (12)

By:

May 7, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

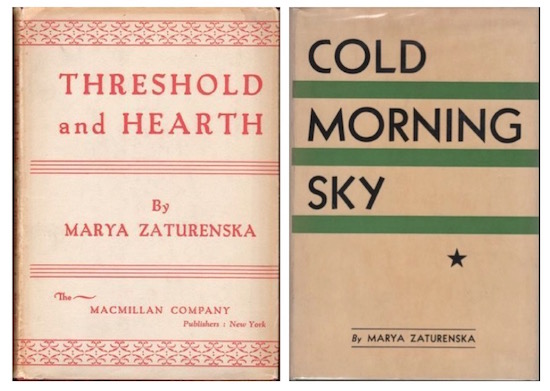

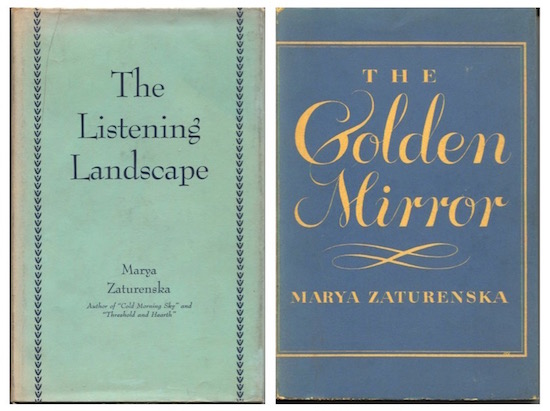

Marya Zaturenska’s Selected Poems (1954)

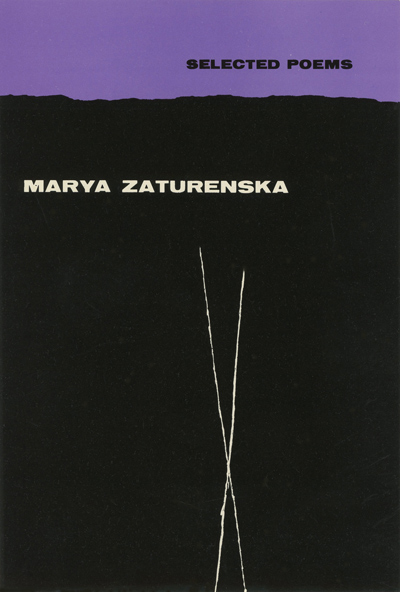

H.D.’s Selected Poems (1957)

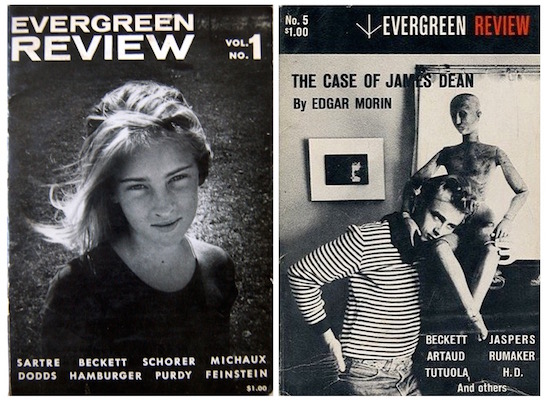

Evergreen Review #s 1 & 5 (1957-58)

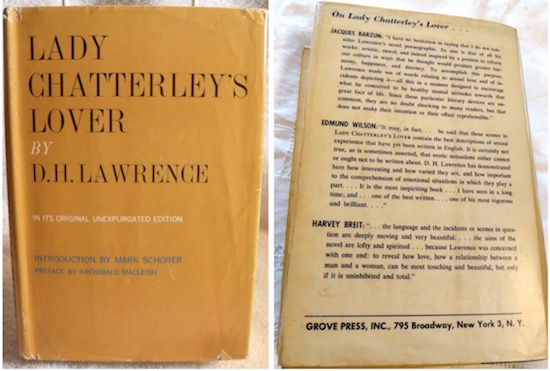

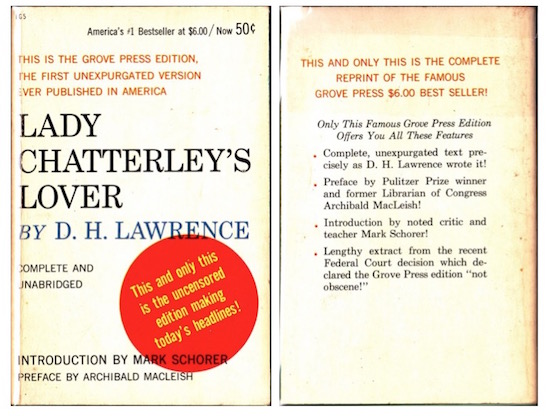

D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928, 1959), cover designs unknown

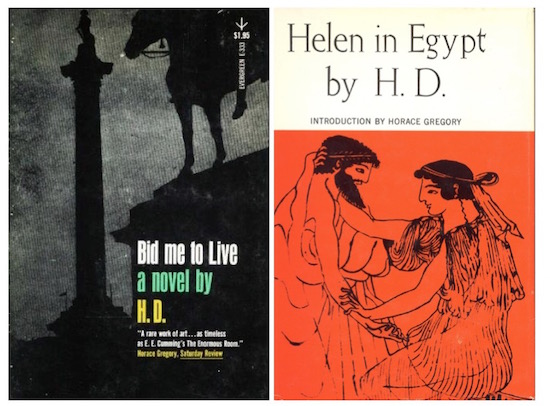

H.D.’s Bid Me to Live (1960)

H.D.’s Helen of Egypt, introduction by Horace Gregory (1961)

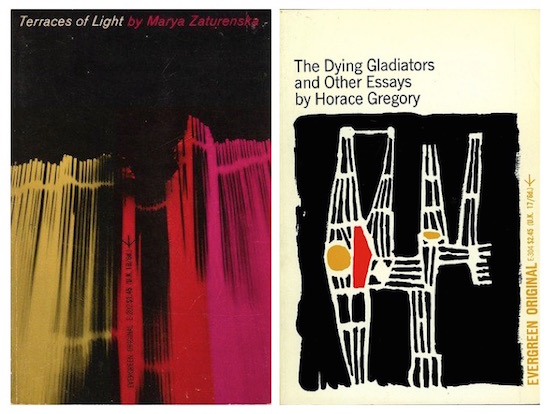

Marya Zaturenska’s Terraces of Light (1960)

Horace Gregory’s Shield of Achilles (1961)

All Grove Press covers by Roy Kuhlman except where noted

Part 1 of “The Lawrence Circles” here.

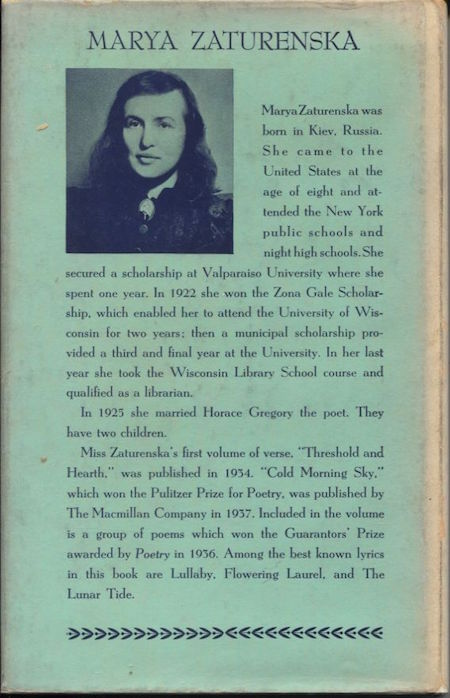

We continue the story of Grove Press’ publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by returning to the career of Marya Zaturenska. Though she’d achieved notoriety before her husband, Horace Gregory, her own first book, Threshold and Hearth (published by MacMillan), didn’t appear until 1934. Unlike the young Marya Zaturensky, the author of these well-crafted, symbolic and metaphysical lyrics isn’t ethnic; except for “City Trees in April” isn’t urban; and she’s certainly not Jewish; one poem is titled “After St. Theresa,” another “Written in a Volume of the Imitation of Christ.” Zaturenska does offer glimpses of her literary world, however: one poem is dedicated to Evelyn Scott (1893–1963), the remarkable British modernist writer; another to Brooklyn-born Léonie Adams (1899–1988) who’ll become U.S. Poet Laureate in 1948; a third to Lewis Mumford, a friend from the Sunnyside Gardens days.

None of these three poems, nor their dedicatees, will appear in Zaturenska’s Grove Press Selected.

When she first received the news, Zaturenska thought it was James T. Farrell playing a practical joke but no, her second book, Cold Morning Sky, really had won the 1938 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry — besting, among others, Wallace Stevens’s The Man with the Blue Guitar. While this would prove to be Zaturenska’s public apogee as a poet, it wasn’t, it should be noted, her artistic peak. Still, Zaturenska’s ear here is terrific and if it hardly seems one attuned to the Depression years or the looming horrors in Europe, there’s also a poem titled “The Emigres” with stanzas like:

Blind outcasts from an age of steel

The steel-sharp age

Knowing retreat is sacrilege

And brings its painful penalties

Perhaps it was too cutting, for this poem would not be included in her Grove Selected.

Though comparatively overlooked, Zaturenska’s next two books were both excellent, with unsettling flashes of harsh intensities and strangeness. Whether such disquiet reflects the poet herself, world politics, or both is rarely clear. Among my favorites from The Listening Landscape (1941) are “In Hostile Lands All Tongues Were Alien,” “Leaves from the Book of Dorothy Wordsworth,” and “The Unsepulchered 1914-1918,” the last an elegy for the Great War dead, including sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brezska, writer T.E. Hulme, and the English poet and painter Isaac Rosenberg.

From The Golden Mirror, “The Vision of Marie Bashkirtseff”; “Daydream and Testament of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal,” “The Affliction of William Cowper” are all indeed steel-sharp and penetrating. Baskirtseff: a Ukrainian émigré like Zaturenksa, also a diarist, artist, feminist, she died aged 25 in Paris; Siddal, English poet, artist, model and the wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, at 32 years old, she was dead; Cowper: superb 18th-century English poet in love with nature, beset by gloom and madness, he suffered greatly, translated Homer, wrote popular hymns and anti-slavery poems and lived to be 68. What was Zaturenska trying to communicate here and did anyone understand her?

I ask because none of the poems just named appear in the Grove Selected, whose contents were chosen by the poet herself. As the book contained no introduction nor other explanatory material, Zaturenska’s reasoning is unknown and though the nineteen new poems reveal no slackening in her lyrical gift, they do show a certain narrowing of her range. Still, “Siren Music” — dedicated to the memory of the poet and critic T.C. Wilson (1912–1950) — is a signal the past won’t be wholly forgotten. Kenneth Rexroth, writing in Saturday Review, praised the book, noting Zaturenska’s austerity and reckoning her achievement just short of Christina Rosetti’s. Other critics were also impressed and her Selected was nominated for a 1955 National Book Award — which, avenging his prior Pulitzer defeat, was won by Wallace Stevens’ Collected Poems.

In between Zaturenska’s first five poetry books came two other important works. The first, written in collaboration with Horace Gregory, was A History of American Poetry, 1900-1940, published by Harcourt, Brace in 1946. Brilliant, maddening, insightful, wrongheaded, passionate, persuasive, ridiculous, not unwitty and often vastly entertaining, it remains an essential cipher for students of both the subject and its authors. This isn’t, to be clear, an anthology but a co-authored critical history without individual attribution; they were in this together, straight down the line, and together they were pilloried.

Delmore Schwartz fumed for three pages in The Nation (“It is difficult to say how much is wrong with this book because there is so much that is wrong and the wrongness is of so many different kinds”); Babette Deutsch patronized it in the New York Times; Allen Tate, writing privately to Cleanth Brooks scoffed “This seems to me to be an appalling book, but it will have great influence in academic circles simply because there is no other in field.”

Zaturenska’s next book, 1949’s Christina Rosetti: A Portrait with Background, was better received. An impressively researched and engagingly written critical biography of one of her literary heroes, the book was also notable for being dedicated to one of Zaturenska’s still living idols, the underpraised genius H.D., aka Hilda Doolittle.

I won’t equivocate here: all of H.D.’s books are worth knowing and if you don’t have any, her Grove Press Selected is a worthy place to start. Though its first cover is among Francine Felsenthal’s most apt designs, it was later replaced by a more striking Roy Kuhlman photographic cover. (Today, this same book is published by New Directions with artwork of their own.)

In 1957 Barney Rosset, with Donald Allen as his San Francisco-based co-editor, started Evergreen Review, a digest-sized literary quarterly. Serving as both an in-house journal and an important outlet for non-Grove authors, issue #1 included a long Mark Schorer essay on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, while issue #5 found H.D. rubbing shoulders with James Dean. One imagines H.D. a Giant fan but here literary and cinema history both are silent.

When Grove finally published Lady Chatterley’s Lover in May 1959, it did so as plainly as possible; there would be no suggestion the novel was anything but a serious literary work, no matter how many orgasms it celebrated or inspired. As supporting documents, Rosset included Schorer’s Evergreen Review piece as an introduction and a preface by poet and former Librarian of Congress, Archibald MacLeish. On the back cover were testimonials from critics Jacques Barzun, Edmund Wilson and Harvey Breit.

In New York, when copies of Chatterley deposited for mailing were confiscated by the Postmaster on obscenity grounds and Grove filed suit in Manhattan federal court. The resulting case, Grove Press, Inc. v. Christenberry, was decided on July 21, 1959, in a landmark decision by Justice Frederick van Pelt Bryan. Chatterley, he opined, had literary merit, wasn’t obscene, and averred further that the application of vague postal obscenity law to such literary works was both unconstitutional and “inimical to a free society.”

Though Chatterley became a best-seller, Grove itself didn’t see huge profits from it. There were legal costs and, because Lawrence’s text had no U.S. copyright, once Chatterley was freed, other publishers brought out their own competing editions. Grove would try to distinguish its version as the first and most famous one but as long as the “dirty” parts were present, how many readers or booksellers would care?

Lawrenceians are a contentious lot and though some disagree, I think Chatterley is a tremendous novel. if it doesn’t always show Lawrence at his very best, it does so many things so well — is so poetically charged, so purposefully discomfiting in its social, political and sexual conflicts and so grasping for viable language of intimacies — that I couldn’t possibly dismiss it nor take it for granted. Asked for a blurb, I’d offer this in conclusion:

“Come for the sex — stay for the coal!”

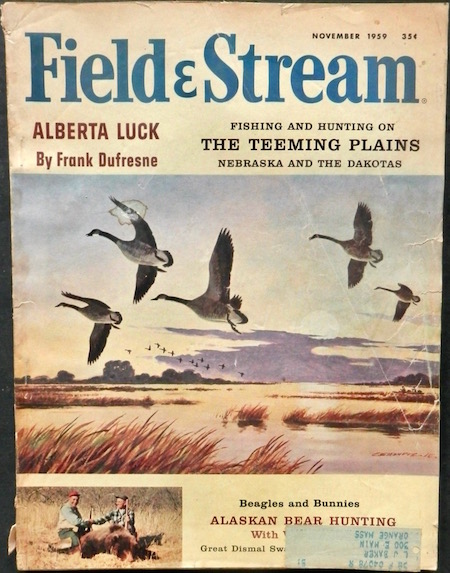

Writing in the November 1959 issue of Field & Stream magazine, humorist Ed Zern offered his own insightful review:

Although written many years ago, Lady Chatterley’s Lover has just been reissued by the Grove Press, and this fictional account of the day-to-day life of an English gamekeeper is still of considerable interest to outdoor minded readers, as it contains many passages on pheasant raising, the apprehending of poachers, ways to control vermin, and other chores and duties of the professional gamekeeper.

“Unfortunately, one is obliged to wade through many pages of extraneous material in order to discover and savor these sidelights on the management of a Midlands shooting estate, and in this reviewer’s opinion this book cannot take the place of J.R. Miller’s Practical Gamekeeping.

Though H.D. initially wished Bid Me To Live to be published pseudonymously, more history- and market- minded forces prevailed. Set in England in 1917, the novel is a roman à clef including such real-life personages as H.D.’s husband, Richard Aldington, back from the war; his mistress; her platonic but mesmerizing friend D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda; H.D.’s college sweetheart, Ezra Pound; and Scottish composer and musicologist Cecil Gray, who’d father H.D.’s daughter. (H.D.’s long-time female partner, Winifred Bhryer, hasn’t yet appeared.) “A rare work of art,” declared Horace Gregory in Saturday Review, “as timeless as E.E. Cummings’ The Enormous Room.”

Helen of Egypt was the last book published in H.D.’s lifetime. In his introduction, Gregory called it a “new kind of lyric narrative, one in which the arguments in prose act as a release from the scenes of highly emotional temper in the lyrical passages.”

What is Achilles without war?

it was Thetis, his mother,

who planned this (bridal and rest)but even the gods’ plans

are shaped by another —

Eros? Eris?

From the jacket copy of Terraces of Light:

“In this new volume by the Pulitzer Prize poet, readers will discover a fresh evocation of timelessness in the modern lyric verse, and a poet who belongs to no school or clique. With their many innovations in musical variety, and their felicity of imagery and word, these poems have no contemporaries in American verse. Their emotional depth and passion, their moments of vision are rare in any age; perhaps their closest affinity is with the poetry of Boris Pasternak.” Favorite poem: “The Garden at Clivenden (Germantown, Pa. 1777),” which is especially pleasurable to read before and after Thomas Pynchon’s like-placed 1997 novel, Mason & Dixon.

From the jacket copy of The Dying Gladiators:

“The ‘dying gladiators’ of the title essay — those comic and pathetic mock-heroes created by Samuel Beckett — serve as the focus of a brilliant and penetrating analysis of the plight of the hero in contemporary literature…” Favorite pieces: “Poet Without Critics: A Note on Robinson Jeffers” and “Wyndham Lewis: The Artist at War with Himself.”

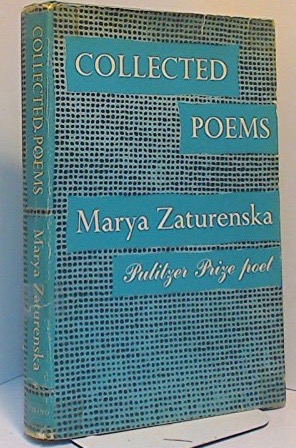

Published with an appalling dustjacket by Viking in 1965 and dedicated to the recently deceased Pascal Covici, the Collected Poems of Marya Zaturenska isn’t anything like what its title suggests. As with her previous Selected, the author here offers neither an introduction nor any other indication that, in fact, this Collected includes but half of the poems from her previous books. All the excellent poems omitted from the Selected remain unaccounted for, as do others besides. Though the exceptional poet and future H.D. biographer Barbara Guest’s New York Times review lauded the Collected, it’s curious that she didn’t mention the book’s many missing poems. Was Guest’s relatively brief review poorly edited? In any event, just as Zaturenska once forsook Zaturensky, so too did the post-Grove poet sadly forsaken large portions of her better self.

NB: Though the field of Marya Zaturenska studies is nearly barren, there is one revelatory, essential exception. Published by Syracuse University Press in 2002, The Diaries of Marya Zaturenska, 1938-1944, edited Mary Beth Hinton with an introduction and notes by Patrick Gregory — Marya and Horace’s son, and himself a former book editor — goes some way towards presenting the poet’s brilliance and her often fraught mental and physical condition during these years. Patrick says it plainly: oftentimes his mother was not — nor did she consider herself to be — a “nice” person, a fact attested to by the substantial number of literary friends unwilling to indulge Marya’s ego, competitiveness and insecurity. And yet, when she’s not pained and fretful about her health, family and finances, Marya — who spoke no English when she arrived in America; shortly lost her mother; had to quit school to work in a ribbon factory, etc. — is an amazing woman: a great, lacerating literary gossip; far more worldly in politics and contemporary culture than her poetry allows (she sees Eisenstein, she reads Henry Miller, gets both), and a devoted classical music fanatic. Ultimately, she hurt nobody more than herself and knowing that, even her lesser works merit rediscovery and interpretation beyond their technical felicities.

In 2002 Syracuse also published Marya Zaturenska’s New Selected Poems, edited by Robert Phillips. While this handsomely produced volume addresses some of the issues surrounding Zaturenska’s curation of her work, many others are unresolved. Interested readers are guided to all of Zaturenska’s original books, including the shrewdly chosen poetry anthologies — unmentioned above — she co-edited with Horace Gregory. At present, there is no Zaturensky / Zaturenska bibliography, nor does she have an “archive” per se; just bits within the Horace Gregory papers at Syracuse. It remains for future scholars to gather all of her published poetry, prose and what correspondences might survive.

For a detailed account of Field & Stream and Lady Chatterley and the wonderfully deadpan literary hoax involved, see Stephen J. Gertz at Booktryst.

For more on Barney Rosset’s publication of dirty books, see Charles Rembar’s The End of Obscenity: The Trials of Lady Chatterley, Tropic of Cancer & Fanny Hill by the Lawyer Who Defended Them (1968).

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.