THIS: What Goes Around

By:

April 24, 2017

I remember the first Earth Day, but I didn’t know what it was. Some kid on the playground let me know that that was what day we were in, and this was why we should be picking up garbage around the grounds. This miniaturization of the monumental issues that were facing the planet was in a grand American tradition of reducing the revolutionary to the civic; we hadn’t quite worked out the think-globally-act-locally equation. This makes radical change manageable, but at its best I guess it can incorporate a sense of worldwide responsibility into the everyday.

Even so, I still took a lot of days off back then; like the rest of my family, I’d learned not to let gum-wrappers and full ashtrays and bags of decimated fast-food sail out the moving car-window like a dove-release, but garbage that was already there I tended to see as someone else’s karma, and a kind of festive outdoor confetti-drop that I could kick around through and wouldn’t make worse. Neither I nor the kid who dutifully went about collecting trash on that day gave any thought to the sprawling, above-ground landfill that abutted our schoolyard opposite a common chain-link fence; even right in front of us, the immense went unnoticed. The litter-kid at one point mused to me that he’d figured out why the planet had such a pollution problem — because the Earth itself, is a piece of pollution. I think he was confusing toxins with dirt, but when I remember the huge dump next-door, maybe he had a point.

Some things, of course, were so big you could see them from far off, and not worry unduly about what you could do about it. Before and after I came to the Earth Day school, conservationist fables were a staple of my family’s woke, weepy TV-watchfulness — a nighttime special on endangered species titled Say Goodbye; an afterschool special called The Last of the Curlews. We listened dutifully to superstar oceanographer Jacques Cousteau’s warnings; we cared, and like the generations we pioneered, who would come to think that vigilance was the same as action, we assumed that was enough; consumers of information with a byproduct of inertia.

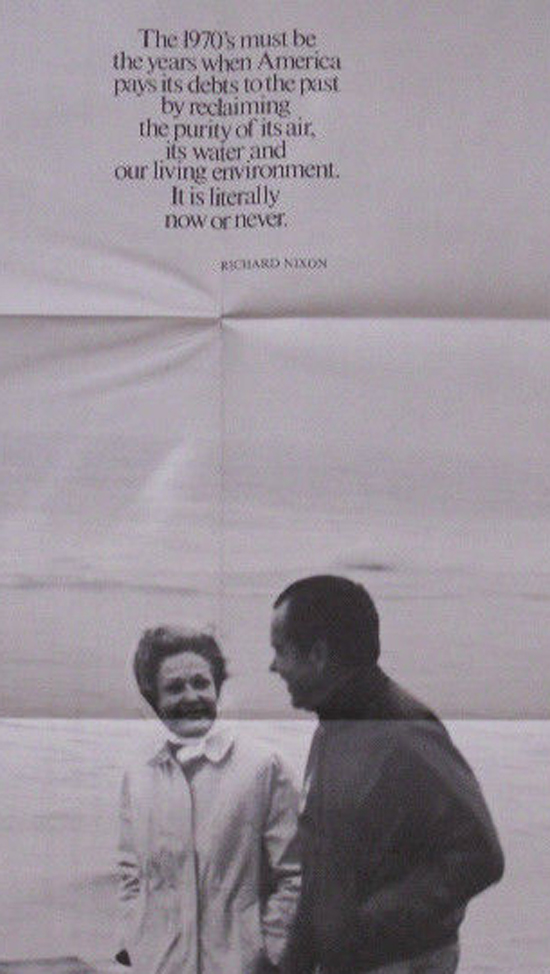

One reason I was mildly surprised to find out there was now an “Earth Day” was that these themes seemed so imbued throughout the culture, from the window of my TV screen. A feature-length Saturday-morning Yogi Bear cartoon, in which he and a menagerie of Hanna-Barbera characters set off in a flying ark to escape all their polluted habitats but then go home to improve the places they came from, was typical at the time. Optimism had its own momentum; Nixon may seldom have told the truth but even he listened to facts, establishing the EPA.

When victory is assured, of course, someone else can always fight for it. The not-a-bang-but-a-whimper dystopias that took up a lot of theatrical movie time had a flipside sense of inevitability; for every in-the-moment disaster flick about a burning building or sinking ship, there were several views of a future in which human survival just dribbles out; through famine (Soylent Green), through disease (The Omega Man), in a new ice-age (Quintet), etc. In that last one, the climate has turned on us; in Rollerball, corporate elites take their privilege out on trees, shooting designer flamethrowers at them for sport — such scenarios were (sometimes literally) as unstoppable as the weather, so why worry, when you could pass the popcorn and watch it coming.

Even my family didn’t do nothing; my dad worked for or started a string of companies in the early 1970s that made carbon-capture devices for smokestacks, and other such remedies. But, either there was money in it or there wasn’t, and some of his products, like the supposedly water-saving strip of metal sandwiched within two slices of styrofoam, for insertion in your toilet tank, were material symbols of the lines between partial-solution and partial-problem that our minds tended not to cross.

The boundary between my playground and the trash mountain was thin, but still not transparent. Things were uphill in many ways; the school itself stood atop an Aztec-pyramid-style trapezoid of earth; the same shape as the dirt-and-grass “forts” at nearby Valley Forge where we charged up and down the slopes and had to fill in a lot with our imagination. These days I wonder what was beneath that perfectly graded pedestal for our school, given what rose a few yards away. The school’s getting demolished this year, and maybe they’ll find out, but then as now I’d rather not. We knew we were having fun; and what you don’t know, in a childhood you’re entitled to or when gathering the courage to face a current ecological tipping-point at which it’s best to not look down, could make the difference in how high a hill you die on.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE