THIS: Alive in the Mind

By:

April 17, 2017

To create your future is to give new destiny to what went before and have a life well relived. It helps to notice the shapes and colors just outside the lines of your apparent existence. Yelena Tylkina came looking for our meeting place in an earth-blue ensemble that unknowingly anticipated the mini globe hanging like a cosmic talisman over the small café, which providentially echoed the great blue ball of energy that the artist would soon tell me had levitated between her and her yoga mentor after several years spent seeking to channel her wild creativity, get it down to earth. It could be that I’m filling too much in; or, as Tylkina put it when I jogged out to the street to keep her from walking right by the place, “I thought some kid had lost his beachball between the fire-escapes!”

There is, of course, an alien enough world right beneath our feet. Tylkina has crossed more of it than many, having gotten out of Belarus in its Communist days shortly before that world ceased to exist, and landing in the America of the late 1980s, already several realities ago. Since then, her truer-than-life meta-memoirs of the old country and her kaleidoscopically surreal painted landscapes of a brave and omnivorous mind have reloaded the canon of creative trauma, feminist self-discovery and populist, eye-popping pictorial epic. To walk through an exhibit of Tylkina’s images with her is to be given a history lesson of a different dimension she knows everything about; to read her stories is to have pictures painted directly on your six or seven senses. To meet up with her was to witness the acrobatics of imagination that spin out when she has nothing but the canvas of the air.

She picked up at the point in the story after the blue globe had bounced out of her mind…

TYLKINA: I didn’t even have to worry anymore, I only needed enough time to put it all on paper. I was so excited; she [the yoga instructor] freaked out. She got so scared she never came back. People told me they’d only read about such an experience in books, so I guess I’m lucky. [laughs]

HILOBROW: Russia has a strong shamanic tradition of its own…

TYLKINA: But I refuse to take any religious side, I only took my own connection with the divine, the cosmos. With a free flow to tap into all kinds of energy; it takes the best, but sees from a distance, without any judgment. Just, “okay, this is my perspective, how could I use it for my art.” People experience different levels. I know people who try everything, and nothing happens.

HILOBROW: Trying is the problem; it’s more about allowing.

TYLKINA: You have to be focused; I did this exercise to determine my shape and form in this society; can I be an artist, and if not, what could I do? Now, I don’t do it as much, because it could make you real kookoo. For instance, I would hear what people were thinking. But you cannot go and tell them this. How to prove? I will keep a diary of someone, what they think about me; two weeks later, I will get a letter, read what the person tells me, and I compare. BINGO. Bing, o. I’m not crazy, it’s just a very unique way [of perception]. With some people, I access this immediately. I know they are thinking of me, and it comes in a very strange way. I’ll “see” them talk, and suddenly I feel a hand, I’m sorry, gripping my vagina.

HILOBROW: I had no idea you’d met the President!

TYLKINA: [laughter] But it’s not degrading; it’s creative energy, for some reason it goes through this channel.

HILOBROW: Sure, that’s a chakra, an anchor.

TYLKINA: And in a second, the person will call. And I thought, “know what, I need to not practice this yoga so much!” On one hand it’s funny, on another, I wonder, “What do they think at that moment? Why such intensity?” But I decide to use these people in my artwork. To release their kookiness, because it’s really bothering me. And they’re incredible muses. Such connection; you have to harvest immediately.

HILOBROW: Your prose stories take in a whole palette of what you were feeling, like when your character is standing before the Council deciding if they’ll let you leave Belarus; impression happens in the realm of the imagination, which makes the imagination one of the senses…so I see how you could sense others’ thoughts on that plane.

TYLKINA: While talking with you, I begin to realize where this imagination came from. I spent a lot of time away from home. Mother working, single woman, and imagination starts when I’m 3 years old, and left in daycare, with other children who can’t go home. And I wake up, definitely between 3 and 4 years old, because I remember extremely clearly the place: I woke up and I see this room, beds, kids, and I said to myself, “Oh my god, these are evil [elves], they’re NOT KIDS”; a woman was peeling potatoes in a doorway, and it’s a dark room, and I see her silhouette and think, “This is Fate. And she’s peeling HEADS.” It was so freaky. And I said to myself, “I’m going to live in Moscow. In the big city.” So, children survive, if your childhood is good — the imagination is there, the roots. I always dreamed about crocodiles, and dragons, and all the fairy tales… amazing, beautiful creatures.

HILOBROW: I absolutely think of your stories as contemporary, grownup fairytales. The logical connections of dreams rather than the progression of rational thought. Like in “The Hunter,” where the drops of blood on snow become like lip-prints on paper, moving in a trail toward him…

TYLKINA: You encourage me to finish the second part. In the second part, they will appear in the cosmos. Like sci-fi.

HILOBROW: I do like how you go from folklore to science fiction — like, once again in “The Hunter,” at the feast, there’s everyone from fanciful beasts who could be out of The Wind in the Willows to, like, aliens.

TYLKINA: To be honest, this is how I see the world. Because, you’re playing games to digest what’s going on. It’s not truly intellectual, it’s more like I’m playing games. “I am here in this strange scenario, how would I think?” Maybe I suffer from not having a personality. Is it possible? I never fit in.

HILOBROW: You have a vivid and unique personality, but you may have cleared some of those walls of the self, what falsely separates us from other minds.

TYLKINA: So if I’m like an element, I’m air. People don’t even feel it as it moves in and out. Fire would be too intense.

HILOBROW: It has that fluidity, and gives you that ability to travel anywhere real and unreal.

TYLKINA: I love to self-discover, because it helps you to go higher.

HILOBROW: The original meaning of “apocalypse” was “unveiling”; not an end but an opening of awareness.

TYLKINA: I think the next creatures after us are going to be smaller. More miniature.

HILOBROW: And still material? I tend to think of them as being more formed from energy.

TYLKINA: No, something will survive. And they will multiply, but they will be much smaller-scale. Large is not working. This size is not working, it should be much smaller.

HILOBROW: Like from dinosaurs to mammals.

TYLKINA: I did a meditation, and I see that everything will be strangely smaller.

HILOBROW: I guess even as far back as H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, this was being foreseen.

TYLKINA: It’s very freaky to me; they kill bees, and now they make drones… it’s spooky. I’m happy with my age, because I experience life in relation to other people, and this creative exploration, this orgasmic state that you can go days and days and days, it’s incredible. So, I experience life. “I’m jumping from the cliff, please join me.”

[The conversation’s neural path winds to Tylkina’s perception of beauty in what others simply view as prurience (a story recounted hilariously in her brief trilogy, “First Love and Pornography”)…]

TYLKINA: So many people approach me in the much younger generation of artists, and they constantly tell me, “We want to show your art, but don’t bring pornography.” To me pornography could be bad abstraction. What is the dictionary definition of pornography? “Bad taste.” Vulgar. I could say, “I’m sorry, but your abstract is pornographic.” Whatever’s going on between people in their memory, imagination, about someone they love, it doesn’t matter how it’s presented, it should be celebrated. It’s a Judeo-Christian bullshit. I’m fighting, and will continue to fight. And I’m tired of hearing people talk about a vagina as something dirty, scary, horrible — I say, “it’s a flower, and it’s going to be a flower, on the cosmic tree, or whatever you want.” [laughter]

HILOBROW: I think it’s the scale model of the universe.

TYLKINA: Yes.

HILOBROW: In Western culture we have such an undeveloped vocabulary for sexuality that we don’t know how to differentiate.

TYLKINA: Sweetie, the Russians are a billion miles behind Americans. In America at least we have foreplay; in Russia it’s either a dirty, horrible word or it’s like [in gruff voice] “let’s do it”…

HILOBROW: That’s what repression gets you; like how the Victorian era on the surface was completely repressed but…

TYLKINA: That’s why I use in my work a lot of flowers, from Victorian times, because —

HILOBROW: There was that “language of flowers”!

TYLKINA: What else to do? Each flower looks like an organ to me too.

HILOBROW: We know Georgia O’Keefe would approve.

TYLKINA: Yeah, but she never went beyond; she was very… timid, in the exploration.

HILOBROW: Do you think she was timid in the context of her times, though?

TYLKINA: Well, I would say, I appreciate her very incredible, scary, loneliness and boredom, and she addressed this in her art — but she’s not a revolutionary person, she didn’t break any rules. I want to break, I want to force people — I want to be more brutal; I realized I haven’t even scratched the surface of my potential; there’s things in my artwork that are still a bit too romantic, it has to be more brutal, and scarier. I’m still writing poetry of the 19th century, in “the language of flowers,” and I want to address some things. For example, a woman sits in a beautiful dress, and holds a cow’s head that’s bleeding on her like a period.

HILOBROW: Okay, that still is poetry. If there’s any law that creative people are bound by, it’s to follow the demands of the fantasy, rather than…it’s only “propaganda” when there’s an external imperative to do a certain message instead of an internal urgency. Be scarier!

TYLKINA: It’s not like I want to provoke people. No, I want to challenge myself. So much is going on, from the past. I’m still probably 12 years old, and I think that I should address my age, and travel back and forth, and address every stage of my life and other people’s.

HILOBROW: Were you always a terror to teachers, like one of them implies in the “First Love and Pornography” stories?

TYLKINA: It wasn’t on purpose! If teachers will act like idiots, I will torture them for a while. And god forbid they say something against my mother. Leave the old lady alone; she has a hard enough life as it is.

[The conversation shifts to Tylkina’s transport to America, after a first refugee-hop to Europe. One of the U.S.S.R.’s infamously persecuted Jews, there was an option that seemed more natural to everyone else than to her…]

TYLKINA: I begged them to not send me to Israel; I said, “Listen, Israel is a small country that’s always on the verge of war, they don’t have time for artists. Let me go to America, I’ll paint better than Pollack. [laughs] You like spots? I could do spots!”

HILOBROW: Did you always have this sense of humor, or was it a product of surviving a state like Belarus?

TYLKINA: Always. I used to like to make my mom laugh. And I’m Gemini, they’re all goofy.

[There ensues an extended digression into astrology, which leads me into wondering aloud if there’s such a thing as a planet with a figure-8/infinity-symbol orbit, which is a more or less straight line to Tylkina bringing up her favorite book:]

TYLKINA: The bottom line of [philosophical space-travel classic] Solaris is, “we tried to extend ourselves to the cosmos, not bring the cosmos to us.”

HILOBROW: That’s the mental model I have for your artwork — so many styles converge into it, distinct but not disjunctive. Do you do a lot of preparatory sketching, or is it more spontaneous?

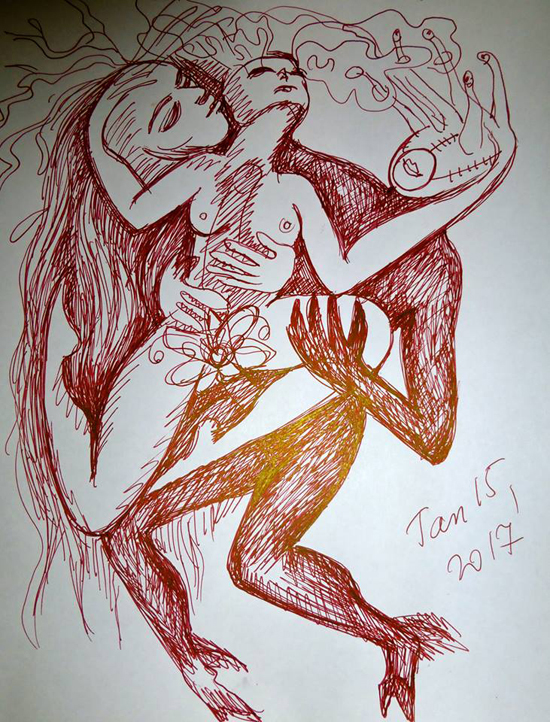

TYLKINA: My drawings, I have thousands of them; because the demons come, and I need to move this enormous energy. After, I see what drawings might be perfect as paintings. It’s exercise, every day, sometimes up to 20, 50 a day. I’m like the fly making eggs. [laughs] You know, the butterfly, when they’re nervous, they immediately lay eggs, up to three times more than usual. They think, “maybe I’m going to die.” Maybe I’m the butterfly that constantly thinks that she’s going to be caught, and killed. I think that you have this nervousness inside, it’s a very unique nervousness that, “today may be the last day, I have to produce as much as possible.” I cannot explain this. It’s workaholics, coming from what?

HILOBROW: Well, it’s drawing on the energy at the core of life.

TYLKINA: I work like it’s the last day of my life, but I have no fear of death, whatsoever.

HILOBROW: You seem very upbeat. I’ve learned a lot from you already because I get the impression you’ve cultivated an outlook that, just because there may be no hope is no reason not to keep going. One never knows what’s ahead.

TYLKINA: I think on the inside, I was born a more optimistic person, and life did make it very very hard for me to get a grasp of reality. I was probably a bit of a superficial person, or too goofy… it was always the bicycles, or sport, or mischief… some people never find that core. Childhood, beside all those predators who tried to take advantage of you, was… for my personality, it was great to have the outdoor freedoms. To run; no worries; I never had anyone supervise me. Totally Jungle Book. [laughs] No shoes, summertime, running around, and I lived between three cemeteries — I was obsessed with death; I wanted to see people go in the ground, I wanted to check every coffin, you know the open coffin; and they looked so peaceful to me, and I said, “They have some wisdom.” Because they look to me like they know better than the people who had buried them. Hysterical, stupid — after the funeral they’d get drunk in the cemetery. And all my life I wanted to meet a person who has some wisdom. Unfortunately. [laughter]

… And you know that I dug graves? I was too young to understand. I thought that, with a fresh grave, if you dig, you get connected with the spirit. And not interrogate; I wanted to have an interview. And I was digging so many graves the police came. And that time I’d decided not to bring a shovel with me. I said, “Okay, this is the last time”; I’d reached the point where I couldn’t move the coffin. Imagine the energy; 8, 9 years old, digging what took two or three guys to cover, and me digging out. And I didn’t realize that I’m terrorizing people; my quest was to get connection with the spirit. And I’m walking at night, in the cemetery, and police are standing there; big guys who said, “Hey kid, did you see bandits here?” “No, what?” “They’re digging graves! What are you doing here?” I said, “I’m here to catch them.” [laughter] “No no, you go home!” And only afterwards I realized that I’m hurting someone.

HILOBROW: That is a unique childhood hobby.

TYLKINA: I look back and I say, “I know I’m not imagining this,” but think about the enthusiasm. Thank god the committee of athletic people, you know, in Russia they’d go from school to school to school looking for athletic students, so they’d say, “Hey kid, come over”; and they saw me playing and assigned me to some athletic school. Otherwise I might have kept doing something else. [laughs]

The conversation took us down several other childhood-village paths and contemporary studio epiphanies and misadventures before we drifted out through New York’s Lower East Side to part at our respective subways. At an earlier art opening, Tylkina had spoken of the familiar terror of Trump, and wondered if she had somehow brought the tyrannical past across the ocean with her. But I think you should follow this woman wherever she wanders, because she’s smuggled in a significant supply of the future to go around.

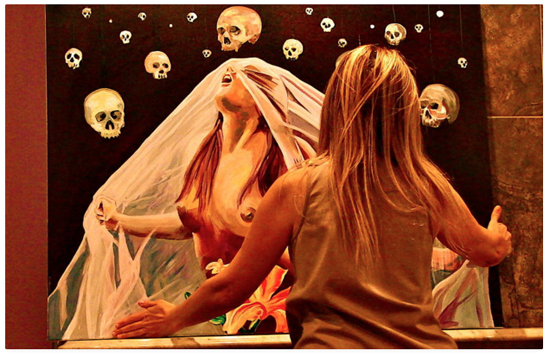

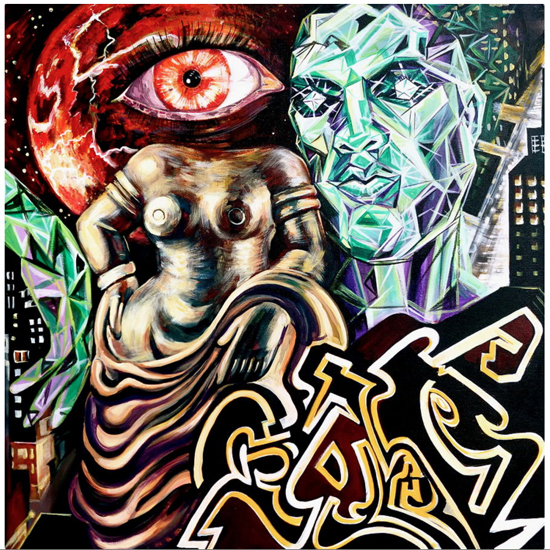

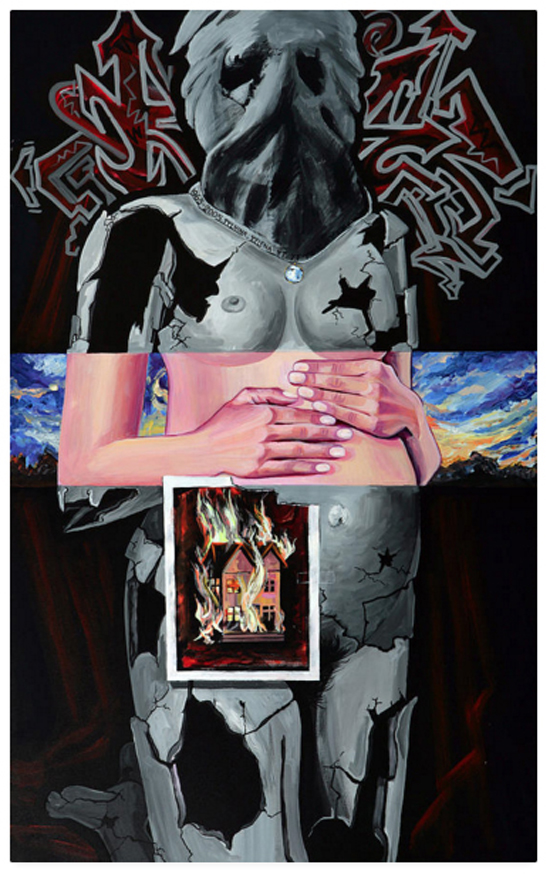

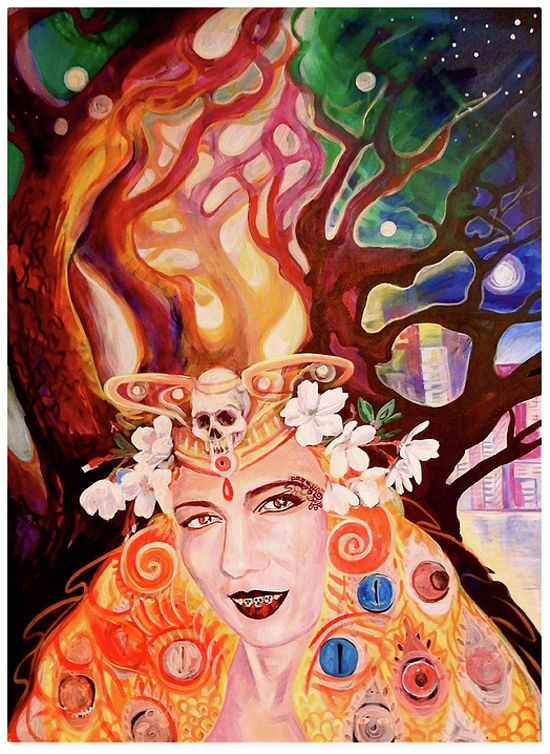

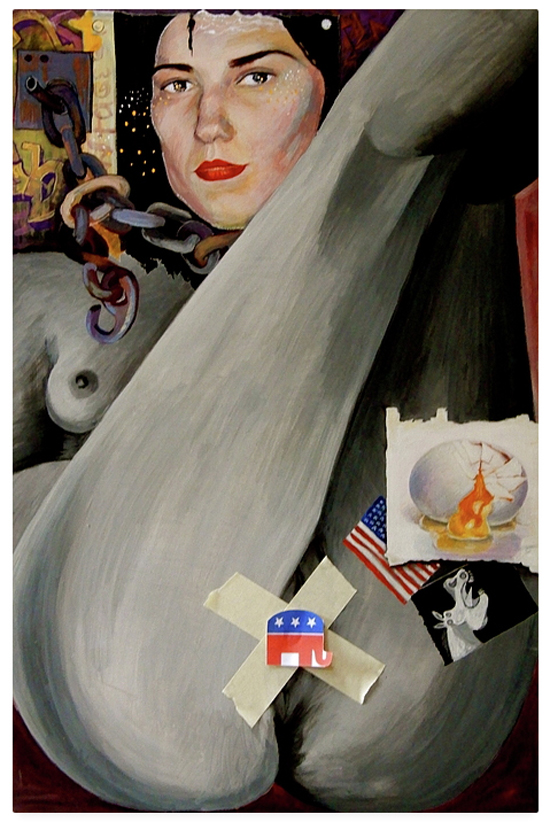

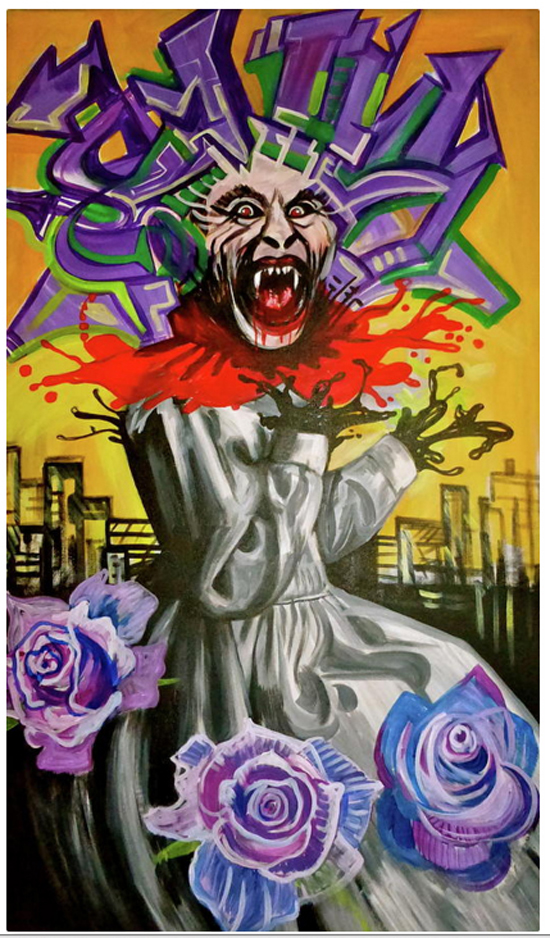

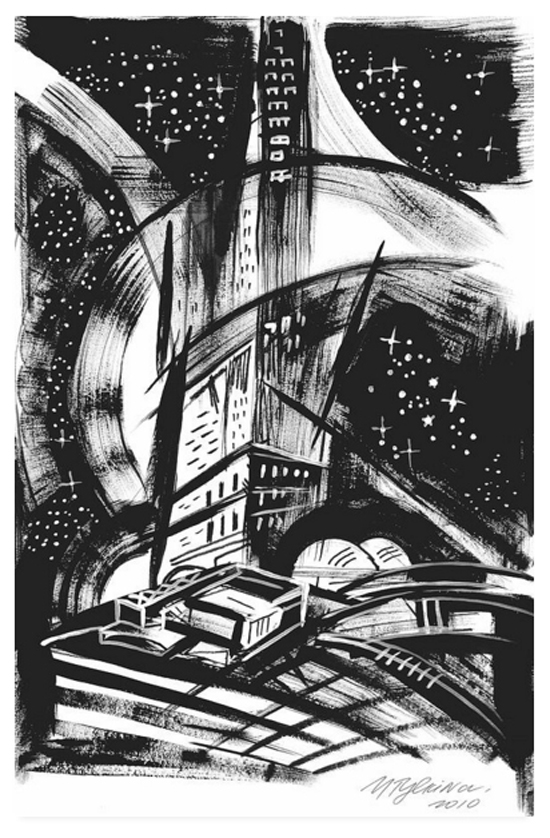

All images by Yelena Tylkina; top to bottom: “Looking Glass,” 2015; “Birth of Venus,” 2014; “Dancing With My Fingers,” 2017; “Queen of the Burning House,” 2009; “Astoria Park in New York,” 2017; “Body Censors,” 2017; “Purple Medusa,” 2016; “Sci Fi City,” 2010; “Drink & Draw” sketches, 2017; “Postcard From Death,” 2016

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE