THIS: Soul Search

By:

April 3, 2017

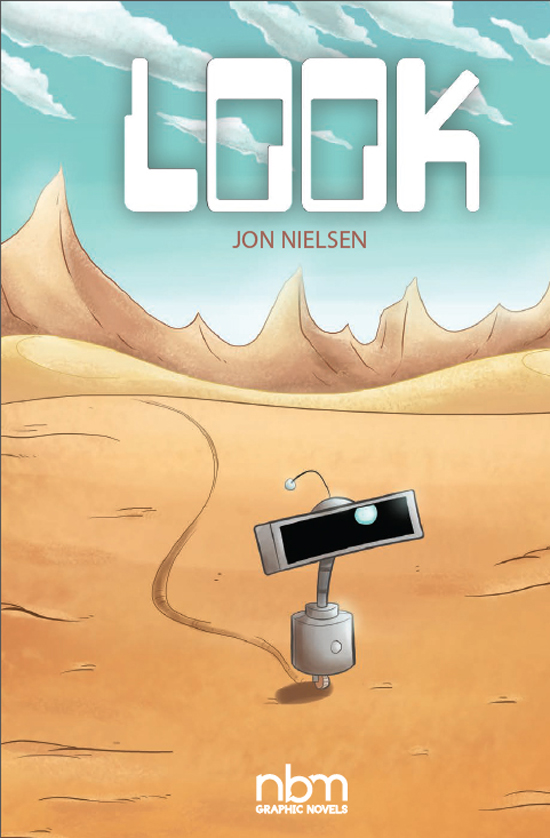

We expend so much worry on the end of the world, that we neglect to plan for what comes next. The languid melancholy of post-life is a reverse-idyll, at the other end of time from mythic, originary golden-ages, that we don’t see very commonly in pop, but does appear prominently, in movies like Wall-E. Jon Nielsen knows such frontiers, having been an accomplished online cartoonist since the mid-Aughts, and in the graphic-novel LOOK, collecting the web-based series of same name, he sees into a future we otherwise won’t.

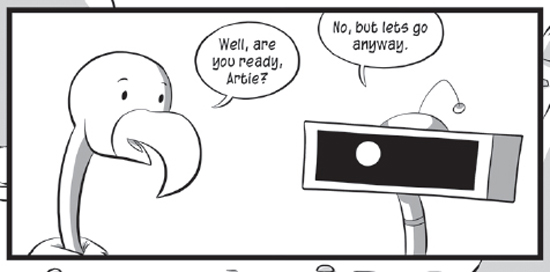

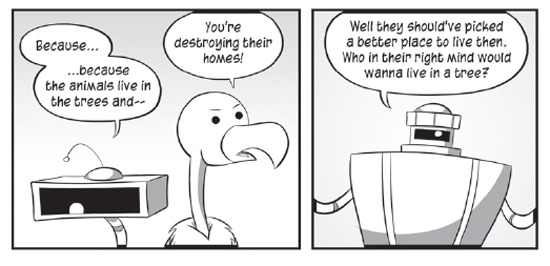

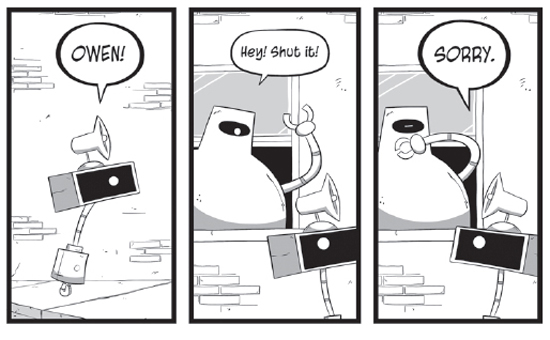

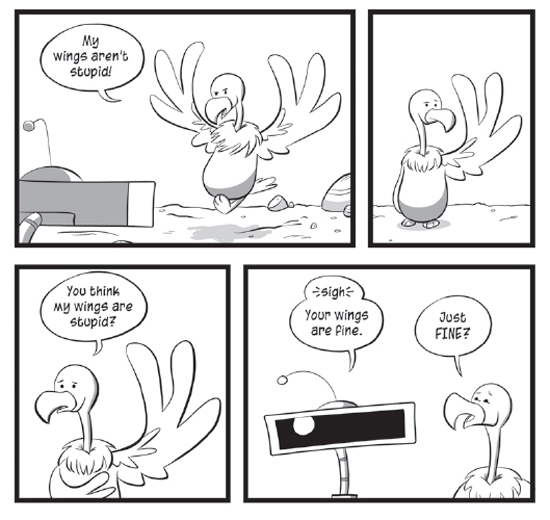

In an unspecified, entropic but not entirely unpleasant century to come, humans are gone, and we didn’t take our toys with us, but they are as alive as we always thought. There are no more creators to rebel against, so the machines — from geometric droids to replicas of the old animal domain — are free to figure out their own identity. The CETI-diagram/charming-hieroglyphic drawing style and dry, sly humor convey a storybook feeling that can veer into shock and pathos at pivotal moments. I spoke with Nielsen about the ideas running deep between his lightly wrought lines.

HILOBROW: It’s a highschool-English commonplace that humankind moved from the Grecian tragedy of the “great man” brought low by his own faults, to the “common man” crushed by forces beyond his control. It’s possible that, with the whole world picked over, we’ve also gone from the quest to the wander — is this what forces us to find what’s within, rather than just stumble across what’s outside of, ourselves?

NIELSEN: There’s something romantic about wandering. Leaving behind your responsibilities and just letting life take you wherever it will. I don’t think that leaving behind everything you’ve ever known is a surefire way of finding yourself but I can definitely understand the appeal of the idea. The wandering hero is also a favorite trope of mine, Hellboy and Doctor Who being great examples. They wander around, solving problems they find along the way, usually while trying to solve a bigger problem or answer an important question. Man, I’d watch that show.

HILOBROW: LOOK poses a succinct but significant hypothetical: among humans, it’s a matter of debate (if fervent belief by many) whether we have a creator, but for the automata of your book, there’s no question. Would this certainty make us any less restless about our purpose?

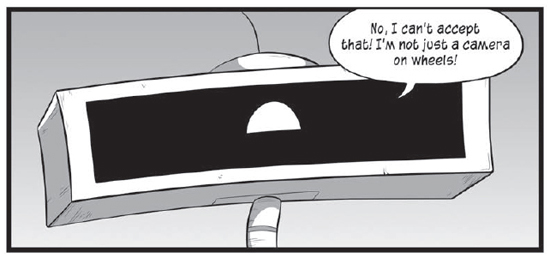

NIELSEN: “Why are we here?” — or more specifically “Why am I here?” — is a question many people struggle with on a daily basis. These robots know exactly why they were made and what purpose they were meant to fulfill. If we as humans knew exactly who or what made us and why, I don’t know how different the world would really look. We’d still find questions to ask and, like [LOOK’s leading machine] Artie, continue to dig for deeper meaning in our accepted truths.

HILOBROW: Related to that, free will seems a hard concept — or even activity — for living beings to accept. Humans don’t seem to inherently know what to do with themselves, and the characters in LOOK are wedded to their old functions mostly because it’s their only frame of reference, not their own initiative. Context causes discontent, and Artie dares to take it into consideration…is knowledge power, or is it vulnerability?

NIELSEN: I don’t want to give too much away, but there is one character in particular who learns that his intended function, one that he’s been performing for countless years, has become obsolete. This revelation completely breaks him and shatters his spirit. He suddenly believes his entire life to be a meaningless lie, acting out in anger at those around him. This is in direct contrast with our main character who, when told the truth of his creation, rejects it entirely and takes it upon himself to give his life new meaning. Our choices define us, more than anything else.

HILOBROW: Ironically, early robots were conceived of to perform tasks, while the “thinking machines” of today were designed to achieve understanding — this is an outsourcing of what philosophers would feel is our quintessential function as human beings. The logical progression of this is for the machines to no longer need us — not to “take over,” which presumes that we have any use at all, but to leave us behind, as in A.I. or Her. Are we evolutionarily driven to replace ourselves, and in some way perpetuate an essence we ceased to recognize as our own?

NIELSEN: I’ve always imagined a sort of merging with science. Whether that’s cybernetics or putting our brains into supercomputers, I think it’s more likely that we’d strive towards improving humankind directly rather than indirectly. That said, I recently read somewhere that an AI that is smart enough to purposefully fail the Turing Test may have already been created. If that’s true, I would like to officially and proudly proclaim that I am eager to serve our new robot overlords.

HILOBROW: The “answers” to existence are not simple, but the style of LOOK is, in visual economy and verbal brevity. Is compression a good way to let narrative textures collect around the story, and in the space between page and reader?

NIELSEN: I believe so! Conveying a story’s messages in a concise and simplistic way is very important to me. It’s so easy for a writer to get caught up in witty dialogue, big words, and the minor details of worldbuilding that they lose sight of the actual story they set out to tell. Like you said, I apply the same philosophy to the art. I think the reason why I love cartooning so much is because it’s all about simplifying and preserving only the most important details.

HILOBROW: There are fairytale aspects to this book, and happier endings than we envision when we picture a world without us. Is it replenishing for pop-culture and futurist fantasy to reinvent folklore every now and then?

NIELSEN: I think so, yes. It’s a lot of fun to play with those old ideas, modernize them, and expand on them in new directions.

HILOBROW: The humor is gentle and the consequences soft-spoken in LOOK, though there is something of the indifference and even brutality of nature in the way the characters relate. How do you keep the innocence and sense of comedy in a story that has as many primal dangers and regrets as this one sometimes does?

NIELSEN: It can definitely be a tricky thing to balance! I feel that telling a story with a lighthearted tone helps the grim scenes have more impact. They hit harder. Also — and I’m sure this goes for most authors — I tend to lean towards worlds that are fun for me to play in. Writing an inherently grim story is not as interesting to me, I need a bit of goofiness to keep me invested.

LOOK is available from NBM, all relevant data here.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE