INTO THE GROVE (6)

By:

March 18, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

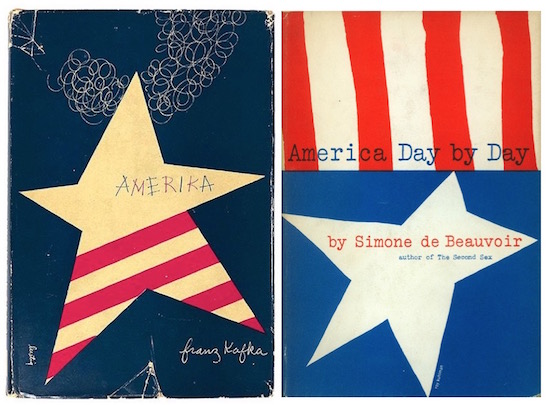

Simone de Beauvoir’s America Day by Day (1948, 1953), translated by Patrick Dudley

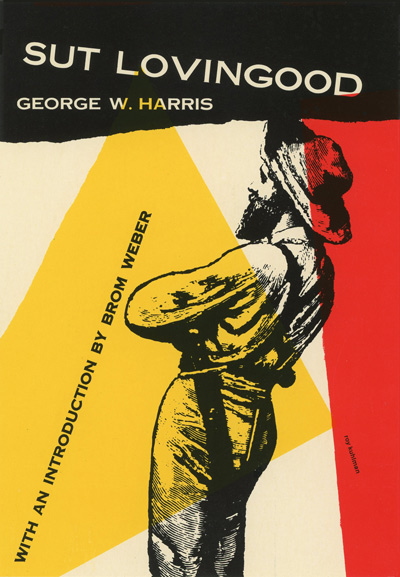

George Washington Harris’s Sut Lovingood, edited and with introduction by Brom Weber (1869, 1954)

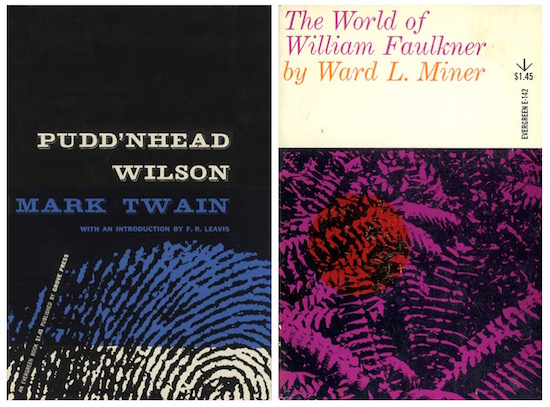

Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894, 1955), introduction by F.R. Leavis

Ward L. Miner’s The World of William Faulkner (1952, 1959)

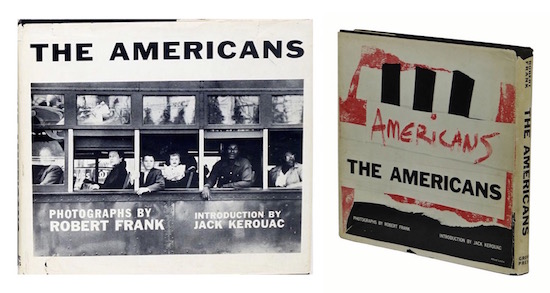

Robert Frank’s The Americans, introduction by Jack Kerouac (1958)

All cover designs by Roy Kuhlman except The Americans by Alfred Leslie

For all of Barney Rosset’s interests in world literature and culture, Grove Press couldn’t have been more American and — as befits a company founded upon returning Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man to print — its catalog would include many books that both recognized and challenged the nation’s highest ideals.

First published in France in 1948, then in England four years later, and finally its country of origin, Simone de Beauvoir’s America Day by Day is a hugely entertaining, often brilliant account of the author’s first visit to the United States. Dedicated to Ellen and Richard Wright — the recent Brooklyn expatriates whom Beauvoir had befriended in Paris — the book follows the French existentialist as she lectures her way across Cold War America from January to May 1947: New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Reno, New Orleans and numerous points in between. Expressing both affection and scorn — especially for America’s unvarnished racism — Beauvoir sees Louis Armstrong at Carnegie Hall, digs cowboy songs on a western jukebox, recalls McTeague via Greed in Death Valley, begins her momentous, ill-fated, affair with Nelson Algren and much, much more. Anyone might quibble with this or that observation but in all, Beauvoir deserves a vaunted place on the American travelogue shelf that also holds Theodore Dreiser’s Hoosier Holiday (1916) and Henry Miller’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945).

Roy Kuhlman’s cover design is almost certainly an homage to that of Alvin Lustig for Franz Kafka’s Amerika, translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, and published by New Directions in 1946.

George Washington Harris (1814-1869) might be the most important antebellum American fiction writer almost nobody reads anymore. Born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania but a long-time resident of eastern Tennessee, Harris worked in a variety of occupations, none too successfully, and began contributing humorous sketches to newspapers in the mid-1840s; in 1854, Harris’ first Sut Lovingood story appeared in the New York-based sporting paper, Spirit of the Times. A feral, highly irreverent product of the mountain south, the Sut Lovingood character became Harris’ primary creative vehicle and perhaps his alter-ego too. In any event, the stories were widely published before being collected in book form in 1867 under the complete title, Sut Lovingood, Yarns Spun by a Nat’ral Born Darn’d Fool, Warped and Wove for Public Wear.

There are reasons for Harris’ plunge into obscurity. Today, it’d be easy to cite Harris’ casual racism as the mark of someone better off forgotten but this would also be misleading, as if

his banishment from the “good books” racket somehow redresses the century of American — not Confederate — racism that followed his death. (Skeptical Yankees might note the complete absence of blacks from Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas (1871) before disagreeing too strongly.) The greater problems with Harris are twofold. First, he wrote in a phonetic dialect which, at quick glance, makes Finnegans Wake look like Dr. Seuss. But — as with Joyce — reading Harris aloud makes all the difference and the author’s sensitivity to the sounding of voices reveals itself as remarkable. Second, Harris isn’t just unkind to southern blacks. Sut Lovingood gleefully satirizes, disrupts and torments everyone — white clergy and gentry included — with such outlandish humor and extravagant violence one could easily call it cartoon-like were Hanna-Barbara’s Tom and Jerry films not many decades away. Some of the most provocative criticism of Sut Lovingood appears in Edmund Wilson’s epic survey of Civil War literature, Patriotic Gore (1963), from which I’ve extracted the following blurbs:

“Sut Lovingood… is always as offensive as possible.”

“By far the most repellant book of any real literary merit in American literature.”

“Crude and brutal… an American institution!”

“Rabelaisian… often indecent… runs to extravagant language and monstrously distorted descriptions… always malevolent and always excessively sordid… caricature at its best!”

[exclamation marks added]

Wilson’s strong reactions suggest why a devoted radical like Barney Rosset could find Harris’ anarchist Smoky Mountain man — or is Sut even a nihilist? — a character worth reviving. That said, the Grove Press Sut Lovingood is probably not the one to have. Hoping to surmount the dialect issue, editor Brom Weber modernized and slightly expurgated Harris’ original texts, diminishing both their literary and historical value. Better to take Sut raw, like Flannery O’Connor and other inheritors of Southern grotesque had done, and see what happens.

Mark Twain actually reviewed Sut Lovingood as a San Francisco journalist; later he wrote a variety of books confronting the specter of American racism, of which the novel Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) is among the best. Edmund Wilson likens Sut to members of William Faulkner’s fictional Snopes family, first introduced in Sartoris (1929) and later featuring in a trilogy beginning with The Hamlet (1940). In the still insightful The World of Faulkner — originally published by Duke University Press — author Ward L. Miner notes the Mississippian’s familiarity with Harris and other antebellum “Southwest” humorists including Johnson Jones Hooper, Thomas Bangs Thorpe and William Tappan Thompson.

Widely and properly celebrated as one of the greatest photography books of all time, there’s little I can add to the praise for Robert Frank (b. 1924) and The Americans save astonishment and gratitude, both for the Swiss émigré behind the camera and the French-Canadian kid from Lowell, Massachusetts who introduces him: “After seeing these pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin” — Jack Kerouac.

NB: In 1998, the University of California Press published America Day by Day in a new and generally superior translation by Carol Cosman, with an introduction by historian Douglas Brinkley. This is now the preferred version of Beauvoir’s remarkable work.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.