America Obscura (5)

By:

November 15, 2016

HILOBROW friend Andrew Hultkrans is a legendary freelance journalist; we have admired his range, erudition, and virtuosity since the early ’90s, when he was a columnist at MONDO 2000. We’re proud to publish this series of essays by Andrew, each of which originally appeared (as noted) elsewhere.

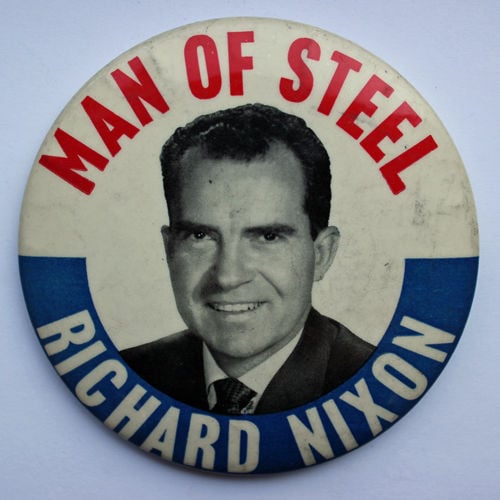

Richard Nixon: A Great American

My first media memory is of my father sitting me down in front of the TV on August 8, 1974 to watch President Richard Nixon deliver his resignation speech. I had just turned 8 on August 1, the date on which, as I learned years later, Nixon had privately decided to resign the office. With little context other than my father’s insistence that “This is important,” I watched as an older man, sitting at a desk and clutching a pile of papers, stared into the camera and delivered a short speech in a rich baritone voice. He seemed at once avuncular and duplicitous, sincere and self-serving, forthright and evasive. If I’d known at the time the by now painfully familiar refrain of the Wall Street settlement, I’d have described him as a man who appeared to be accepting some form of responsibility without admitting or denying wrongdoing.

As I grew older, I became interested in Cold War American history, an era throughout which Nixon played pivotal, if not always noble, roles. Movies focused my attention on this strange figure, this awkward usurper king, a latter-day Richard the Third from the lemon groves of Depression-era Southern California. All the President’s Men, of course, which like the 1968 campaign ads you just saw, circled around the man without showing him. But also the director’s cut of Oliver Stone’s undersung biopic, numerous documentaries, and the great paranoid thrillers that emerged from under the pall of Nixon without directly addressing him—The Conversation, The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, among others—a cycle of films that accurately evoked the jaundiced, cynical, nicotine-stained mid-’70s of my childhood.

Now, after years of obsessively digesting books, films, tapes, transcripts, and documents by and about the man, I’ve come to the conclusion that Richard Nixon was a Great American. Not great in the sense of transcendently good, because he was far from that. Not even in the sense of towering, world-historical significance, a status he so desperately craved and came close to achieving. No, Richard Nixon was a Great American because he so perfectly exemplified various aspects, often contradictory, of the American character.

He was the ultimate bootstrapper, an ideal exemplar of the Protestant work ethic who realized the American dream of coming from nothing and making it to the top through sheer force of will and hard work. Although he outworked everybody—his nickname at law school was “iron butt”—Nixon still felt the need to cheat to ensure success. What’s interesting about this is not that he was devious, which he was, but that he justified his more unsavory shortcuts to himself with the excuse that—as the CIA used to say during the Cold War—the other side did it first, did it worse, and, in any case, everybody does it. This is, in a nutshell, the mentality of Wall Street and the more corrupt precincts of American government.

Throughout his career, Nixon was driven by a longstanding American suspicion and resentment of “the elite,” a tacit aristocracy that had somehow developed in a nation that wasn’t supposed to have an aristocracy. At his high school, there was a society of well-heeled boys from the area called the Franklins. Nixon, the poor son of a failed lemon rancher turned barely successful grocer, was not destined to be tapped for the Franklins. This understandably irritated him, but instead of rejecting the concept of selective membership clubs entirely, he started his own anti-club club, the Orthogonians, which existed merely to oppose the Franklins. This invokes images of esteemed and exalted grandees of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks carping about Skull and Bones from the comfort of their own lodge.

Nixon had a titanic animus for Harvard, not least because he was accepted on scholarship but couldn’t go, having to take care of the grocery store while his brother Harold was dying of tuberculosis, but also because those privileged Kennedy cocksuckers went there. His early nemesis Alger Hiss had gone to law school there. Later, the Watergate special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, was another Harvard “soft-head intellectual” trying to tear him down. This was, for Nixon, the essence of the hated “Eastern Establishment,” an aristocracy in all but name. Had he only accepted the scholarship, Nixon—and history—might have turned out differently. An entire artery of complaint, one he relied on so often during his presidency, would have been excised from his personality before he’d even entered politics.

Nixon’s situational ethics were also a product of the very American notion that winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing. One of his favorite movies, which he screened repeatedly at the White House, was Patton, starring George C. Scott as the maverick World War Two general. Its opening scene has Scott standing in dress uniform in front of a mammoth American flag, delivering a motivational speech that served, for Nixon and other Vietnam-era hawks, as a kind of national creed: “Americans love a winner, and will not tolerate a loser…. The very thought of losing is hateful to Americans.” The necessity to win at all costs inspired the dirty tricks Nixon used in his congressional, senatorial, and presidential campaigns and fueled his most unforgivable crime—his needless four-year extension of the Vietnam War, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of lives, to achieve a so-called “peace with honor” under terms barely different than what the North Vietnamese had offered U.S. negotiators before he took office.

A corollary of this was Nixon’s overriding concern with “toughness,” with always being perceived as “tough” or “playing it tough.” The Soviets were “tough,” the CIA was “tough,” the first-string varsity football players who used him as a tackling dummy in college were “tough.” Patton, above all, was “tough,” and by golly, Nixon was going to be “tough” too. This rigid, self-conscious standard closed him off emotionally from other people and actually had the effect of obscuring his more subtly brilliant ideas and impulses. And the sad truth was that he was not tough in a conventional physical sense; he was instead quite mincey in his personal comportment, his scrawny limbs never seemed to be in the right place. Nixon did have guts and endurance, but in other respects he was anything but tough. It was bluster masking profound insecurity, as “toughness” so often is.

Nixon was, like many strains, some subterranean, of American culture, deeply paranoid. There are several explanations for this. The pendulum swing between insecurity and narcissism is one. Cold War intrigue, and the spy games that fueled it, couldn’t help but rub off on high officers of government, particularly the president, giving them unsettling glimpses of the “wilderness of mirrors,” a phrase CIA counterintelligence chief James Jesus Angleton used to describe the labyrinthine netherworld of spies, moles, double agents, and triple agents he traveled in regularly. But Nixon’s paranoia seemed to be that of the guilty man—a man who’s spent many years screwing his political opponents through underhanded means—whose own past machinations and behavior have returned to haunt him. Nixon always looked for the worst in people, and deep down, he suspected people were doing the same to him.

Like so many Americans, Nixon was an opportunist, a cynical idealist. He was puritanical about sex, anti-intellectual (while having a brilliant, well-read mind), and not above descending into cornball bathos when it was politically expedient, as in the infamous (if effective) “Checkers speech” that saved his 1952 vice presidential bid. His “small government” rhetoric was belied by his unprecedented arrogation of power to the executive branch and contempt for the legislature, and his visionary, big-picture foreign-policy plans were marred by Machiavellian tactics and frequently irrational orders and actions. Top aide John Ehrlichman, reflecting on the Watergate horrors years later, attempted to explain the entire scandal away by saying, “Some damn fool went into the Oval Office and did what he was told.”

Above all, Nixon was a great believer in not only American exceptionalism, but Nixonian exceptionalism. “When the president does it, it’s not illegal” is all too easily extrapolated to “When America does it”—nuclear weapons, mass murder, torture, indefinite detention without trial, harassing journalists, warrantless wiretapping—“it’s not wrong.” Again, the other side did it first and did it worse, so we’re absolved. Plus, we’re America. We’re never, ever the bad guys.

Nixon was not only a great example of an American generally; he was also crucial to the development of the contemporary American right. Nixon entered presidential politics as a Sarah Palin to Ike Eisenhower’s John McCain, a young, vociferous zealot who could throw red meat (in a dual sense in Nixon’s case) to conservatives and deliver the type of aggressive, hyperpartisan campaign messages his boss found distasteful. Nixon laid many of the foundations, ideologically and in terms of personnel, for today’s right wing—an increasingly extreme, intransigent voting bloc that would never allow him to win his party’s nomination today. Too liberal. Among other sins, Nixon started the Environmental Protection Agency; he instituted price controls; he took the nation’s currency off the gold standard; he enforced school desegregation; he increased the salaries of federal workers; he started the first major federal affirmative-action program; he endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment; he made a fragile peace with the America’s most powerful enemies in ways that were politically risky and out-of-step with his own past right-wing orthodoxy.

Nevertheless, we have Nixon to thank for Roger Ailes, creator and president of Fox News, whom Nixon hired to run the television strategy for his successful ’68 campaign. We have Nixon to thank for Sarah Palin nattering on about the “lamestream media.” We have Nixon to thank, of course, for Henry Kissinger. We have Nixon to thank for all the Bush administration neocons—Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Paul Wolfowitz, and others—who began their political careers as members of his administration. We have Nixon to thank for bilious paleocon Pat Buchanan, a Nixon speechwriter. For good or ill, we have Nixon to thank for Diane Sawyer.

Then there are the legacies that transcend party lines. After delivering the April 30, 1973 speech in which he fired his closest aides, Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, Nixon worried that the inclusion of “God bless America” in his closing sentence was over the top, querying cabinet members and aides on the phone for their opinions on its use. It goes without saying that every president since has deployed the phrase without apparent concern. Check the next State of the Union. A phone conversation with Ronald Reagan that evening neatly encapsulated Nixon’s peculiar sense of piety: “Each of us has a different religion, but goddammit, Ron, we have got to build peace in the world.”

And have you noticed that for decades all presidents and presidential candidates have worn American flag pins on their lapels? Nixon started that, and it’s been amusing to watch the pins get bigger and bigger over the years in a type of sartorial one-upsmanship that probably would have embarrassed him.

After Nixon resigned the presidency in disgrace, he embarked on a multi-decade campaign to rehabilitate his image on the global stage, an effort which, via his books, visits to state leaders around the world, and advice sessions for sitting presidents, largely succeeded. By the end of his life, he was considered an elder statesman of sorts, although one who would never be able to completely transcend his earlier flaws and failures. It sounded odd in 1994 to hear Bob Dole call the second half of the twentieth century “the age of Nixon” at his funeral, but in the intervening years, such absolutes do not jar the ear as they once did. The rehabilitation and revisionism that fueled it went a bit too far. Nixon really did do terrible things—Vietnam, Cambodia, Chile, Bangladesh, Watergate, wanton surveillance and harassment of opponents and critics—but, worst of all, he made already growing cynicism about American politics and institutions permanent through his crimes and coverups. We’re still reckoning with his dark legacy in this regard.

Nevertheless, part of me wishes that we still did have Richard Nixon to kick around. He was as smart as Ford, Reagan, and the two Bushes all put together. He was coldly realistic when it was important to be so, but kept his idealist’s eye on the far horizon, where great things could be done, great changes could be made. This was the Nixon that triangulated China and the Soviet Union, a masterstroke of geopolitical balancing that promised an enduring peace—until Reagan ratcheted up the arms race and proxy wars in the ’80s. There’s one problem, though. Putting a resurrected Nixon anywhere near today’s NSA would spell the end of our remnants of constitutional democracy, let alone our dwindling illusions of a free press. If indeed my “whole world depended on it,” I wouldn’t take the chance.

Talk delivered on October 8, 2013 at apexart in New York as part of its “Double Take” series, which asks pairs of writers to present papers on the same subject. My partner was novelist Christopher Sorrentino. A video of our talks can be seen here.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators