10 Best Adventures of 1976

By:

November 15, 2016

Forty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Seventies Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any 1976 adventures that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Samuel R. Delany‘s Foucauldian science fiction adventure Trouble on Triton: An Ambiguous Heterotopia. Part novel, part treatise, Triton brilliantly (if sometimes maddeningly) deploys post-structuralist theory in order to both illuminate and subvert the story of an unpleasant protagonist’s struggle to acculturate himself to life in a utopian colony on Triton, Neptune’s largest moon. Bron Helstrom, who had previously worked on Mars as a male prostitute, should be happy on Triton — where no one goes hungry, and where one can change one’s physical appearance, gender, sexual orientation, and even specific patterns of likes and dislikes. Helstrom’s problem is that he is an unregenerate individual, an asshole even, in a culture that deprioritizes the notion of the individual. (Shades of Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars.) But Triton is less about Bron, in the end, than it is a critique of utopia, an exploration of the Foucauldian notion of heterotopia, and a semiotic intervention into science fiction’s unexamined ideologies. Should we feel sympathy for Bron, and reject Triton’s social order; or the other way around? Yes and no. PS: Almost forgot to mention that there is a destructive interplanetary war, between Triton and Earth, too. Fun fact: Originally published under the title Triton, the novel’s themes and formal devices are also explored in Delany’s 1977 essay collection, The Jewel-Hinged Jaw.

- Ishmael Reed‘s sardonic historical/hunted-man adventure Flight to Canada. Along with two fellow slaves, Raven Quickskill escapes from an antebellum Virginia plantation. He is determined to make it all the way to Canada; his master, wealthy planter Arthur Swille, pursues him. Reed, in one of his finest, zaniest and most searing efforts, playfully subverts and embellishes a plot seemingly lifted from an earnest abolitionist novel: Quickskill flies to Canada aboard a jumbo jet; the plantation mistress watches Lincoln’s assassination on TV; Swille is a necrophiliac. Everyone struggles to maintain control of this story, while black writing remains inherently fugitive: Quickskill is the story’s author, but Swille’s most loyal (or most subversive?) slave, Uncle Robin, is its narrator; Quickskill’s poem, “Flight to Canada,” is an essential part of his liberation, but it also helps Swille track him down; Uncle Robin refuses to sell his story to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Fun fact: Edmund White, writing for The Nation, called Flight to Canada “the best work of black fiction since Invisible Man.”

- Rosemary Sutcliff’s YA historical adventure Blood Feud. A story about the Varangian Guard — an elite unit of bodyguards to the Byzantine Emperor, primarily composed of Norsemen — that starts in 10th-century England, between the decline of the Roman empire and the lightening of the Dark Ages. Jestyn Englishman, an orphaned shepherd, is sold as a slave to a Viking raider, Thormod Sitricson; he and Thormod become friends and comrades-in-arms, When Thormod’s father is accidentally killed, Jestyn becomes caught up in a blood feud — a quest that takes the two friends to Kiev and Constantinople, where they enlist in the service of Khan Vladimir… and seek revenge. Although written for children, Blood Feud is morally complex: though loyal to his Viking blood brother, Jestyn vacillates between Christian and pre-Christian notions of honor, and the best path to an after-life. Fun fact: Sutcliff is a formidable writer who went from strength to strength. Her early books — e.g., The Eagle of the Ninth (1954), The Silver Branch (1957) are terrific; but so are her late books — e.g., The Light Beyond the Forest (1979), The Road to Camlann (1981). She wrote several dozen children’s books, too.

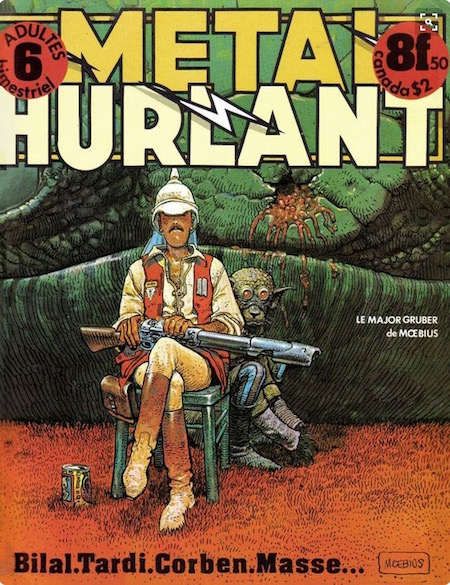

- Moebius‘s sci-fi/western/frontier/apophenic graphic novel adventure Le Garage Hermétique (The Airtight Garage, 1976–79). Le Garage Hermétique is one of the two great capricious comic strips of the Seventies (1974–1983); Gary Panter’s Dal Tokyo, which first appeared in 1983, is the other. Over a four year period, Moebius cranked out two to four pages per month; each month, he challenged himself to solve continuity problems that he’d playfully introduced previously, while also creating new problems. The main plot, to the extent that there is one, concerns the efforts of Major Grubert to prevent outside entities from invading the Garage Hermétique — an asteroid housing a pocket universe, which features, e.g., desert and forest biomes, a city, and a world made of machines. One of these invaders is Jerry Cornelius, a trickster figure whom Moebius lifted from Michael Moorcock’s sci-fi novels; Grubert and Cornelius join forces, eventually, to face a threat to the Airtight Garage. Each installment of the strip, many of which focus on Grubert and Cornelius’s hapless allies, is its own self-contained epic; they don’t necessarily add up to anything larger. Fun fact: Le Garage Hermétique first appeared, from 1976–1979, in issues 6 through 41 of the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Métal Hurlant; Americans first read it in the magazine Heavy Metal, starting in 1977.

- Lionel Davidson’s political thriller/treasure-hunt adventure The Sun Chemist. Igor Druyanov is a historian and scholar, living part-time on the lovely Israeli campus of Rehovot University, and part-time in dreary London — where he is researching a book on Chaim Weizmann’s mid-1930s laboratory work in England. (Weizmann, a real-life promethean character, was a Zionist leader, the first President of Israel, and a biochemist whose acetone production method was critical to the British war industry during World War I.) Although Druyanov’s research is tedious, it seems that Weizmann may have discovered the secret for manufacturing a petrol substitute out of sweet potatoes; if Druyanov can locate Weizmann’s lost lab books — somewhere in northern England — he may be able to help solve the oil crisis looming large in the mid-1970s. (And, as a result, shift wealth and power from oil-rich Arab countries to impoverished Africa.) However, powerful forces are at work to keep Weizmann’s discovery a secret. Much of the plot’s “action” involves biochemistry. But there is some violence, and a night-time chase through Rehovot and Jerusalem. Fun fact: The author, one of all-time favorite adventure writers, was the British-born son of a Polish-Jewish immigrant father; in the 1960s, he made his home in Israel.

- Len Deighton’s espionage adventure Twinkle, Twinkle Little Spy. With the complicity of a Soviet scientist (a kook, who is attempting to establish contact with alien civilizations), the KGB has been stealing scientific secrets from the US government. Major Mann, a CIA blowhard, is sent to the Sahara Desert to take custody of the scientist, who wishes to defect; an unnamed British agent — Harry from The IPCRESS File, or someone else? — accompanies him. Mann notes that their old-fashioned espionage methods are becoming obsolete, thanks to satellite technology; the novel’s title is the unnamed British agent’s world-weary rejoinder. What starts as a relatively straightforward assignment, though, gets murky; Mann and the British agent end up traveling all over the world. A more action-packed adventure than many of Deighton’s spy novels; some of his diehard fans might find it too simplistic, while those who scratch their heads over Deighton’s puzzles might particularly like this one. Fun fact: Also published as Catch a Falling Spy. The final installment in Deighton’s “unnamed hero” novels, which include: The IPCRESS File (1962) Horse Under Water (1963), Funeral in Berlin (1964), Billion-Dollar Brain (1966), An Expensive Place to Die (1967), Spy Story (1972), and Yesterday’s Spy (1975).

- Michael de Larrabeiti’s sardonic YA adventure The Borribles. A tough-minded, violent, bleakly humorous, metafictional yarn about members of a tribe of runaway adolescents — a gritty urban version of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, a fantastical, punk version of Oliver Twist — who are sent on an assassination mission deep into the heart of their enemies’ kingdom. The Borribles are London kids who’ve dropped through the cracks, grown pointed ears, and live by their wits — and their weapons. When the Borribles of Battersea discover a Rumble (one of the large, rat-shaped hominids who compete with the Borribles for resources) tunneling in their territory, an elite group of Borrible fighters from across London — this is a crackerjack adventure — head for Rumbledom in order to eliminate the Rumble High Command’s eight members. It’s an epic journey, even before they reach Rumble HQ — with plenty of treachery and bravery, cunning and derring-do. Their mission isn’t a high-minded one; and the group doesn’t see eye to eye. But they perservere! Fun fact: The subsequent volumes in the Borribles trilogy are The Borribles, The Borribles Go For Broke (1981), and The Borribles: Across the Dark Metropolis (1986). The members of the Rumbles’ High Command are satires of Elisabeth Beresford’s lovable, iconic Wombles.

- Vera Chapman’s fantasy adventure The King’s Damosel. On the day of Lynett’s marriage to Gaheris (also the day of her sister Lyonesse’s wedding to Gaheris’s brother, Gareth), we learn that Lynett was raped as a teenager… and that she is in love with Gareth. Gareth and Gaheris are knights of King Arthur’s Round Table; Lynett, a former tomboy, yearns for a life of adventure; she also seeks revenge. With Merlin’s help, she becomes Arthur’s messenger — her duty is to travel ahead of Arthur’s knights, persuading unruly Lords to swear allegiance to the king. Over the course of the novel, she acquits her duties well… and gets her revenge. There are triumphs and tragedies; a witch and a blind lover; a tear-jerking ending; not to mention the Grail. The novel requires Lynett to forgive her rapist (his ghost haunts her, until she does), which today’s readers may find infuriating; still, this is definitely a feminist story. Fun fact: Either the second or third book in a trilogy; the first is The Green Knight (1975), the other is King Arthur’s Daughter (1976). Very loosely adapted as the 1998 animated movie Quest for Camelot.

- Ira Levin’s political/sci-fi thriller The Boys from Brazil. Yakov Liebermann, a Nazi-hunter who has spent decades tracking war criminals at large, is reaching the end of his career; he’s low on funds, and tired of chasing false leads. However, when an investigative journalist who’d told him that former SS men had been dispatched from Brazil by Joseph Mengele, the infamous concentration camp doctor, in order to kill 94 apparently harmless men (all about the same age, all civil servants) in countries around the world, with the goal of paving the way for “the Fourth Reich,” is killed, Liebermann investigates. It does indeed seem that these men re being killed; but why? And why does each man have a 13-year-old son? A far-fetched plot, but Levin — author of A Kiss Before Dying, Rosemary’s Baby, This Perfect Day, and The Stepford Wives — certainly knows his way around a thriller. Fun fact: At the time of the novel’s publication, Mengele was indeed still at large, in South America. The Boys from Brazil was made into a popular movie, starring Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier; it was released in 1978. My stepmother took me to see it, that year (I was 11); she was so disturbed that, on the way home, she knocked down a light pole with our VW Bus. Memorable!

- Victor Canning’s The Doomsday Carrier. Aficionados prefer Canning’s oddball 1970s thrillers to his previous, better known works because, after an emotional crisis in the late ’60s, he began writing stories whose subjects were meaningful to him — in which the good guys were the bad guys. John Rimster is an agent of the British Secret Service’s dirty tricks department; he’s assigned to look after Jean Blackwell, a research assistant from a biological warfare research establishment… who has infected a chimpanzee with a modified plague bacillus, then inadvertently allowed it to escape from the laboratory. While keeping the story under wraps, the government must find Charlie the chimp within three weeks! Charlie, meanwhile, is having a glorious time exploring the English countryside. Rimster, I forgot to mention, is an alcoholic. Does he still have what it takes? Fun fact: Canning makes his opinion clear: “Everyone was happy, particularly the apes in dark suits who might one day for political or military reasons decide to use the silent weapon of plague to avoid the open and honest brutality of the sword.”

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.