THIS: Master of None

By:

November 14, 2016

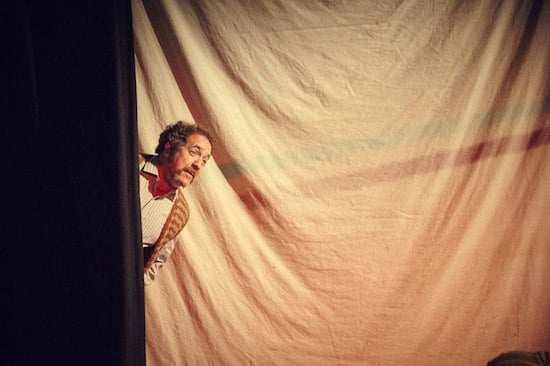

They don’t even fake ’em like they used to — and there’s no need to try. Artifice was impossible in the campaign of 2016 — with everything bad there was to know about both frontrunners leaked or self-proclaimed daily — and voters and media alike seemed to drift from a consideration of facts to a connoisseurship of stagecraft. The old lavish kind has been defunded, so a sort of thriftstore Prospero preambles us into CANT, a closing argument on democracy by playwright/director Ian W. Hill (who’s also that Prospero), running through November 20 at The Brick in Brooklyn, USA.

After the semi-surreal prologue the show sets into the kind of soul-inquest (autopsy?) that American democracy didn’t quite conduct on itself this year. The set is skeletal, though it’s anything but bare, as an ensemble of 17 actors (14 physical, three disembodied) spend the first half of the show debating the merits and discerning the motivations of a tabula-rasa presidential candidate, with the Orwellian Thornton Wilder name of “Our Boy.” Boy is the actual emptiness at the center of the show, with everyone in their way protectively circling him, so to speak, but facing inward, to project whatever they want him to be.

Mass-culture archetypes litter the narrative like popped balloons on a convention-hall floor; peeled from some WWI-era propaganda poster, a folksy Uncle Sam and vaudeville-French Miss Liberty (David Arthur Bachrach and Ivanna Cullinan) briefly ponder the worrisome course of the American experiment like sideshow deities before getting shuffled off the world stage; two reporters out of a 1940s B-movie metropolis (Amanda LaPergola and Derrick Peterson) dig into Our Boy’s past, their anachronistic moxie and speech-patterns and wardrobe and principles marking them as personifications of an obsolete social role; Our Boy himself is played simultaneously by two actors (John Amir and Michael Rishawn), white and black, and thus modern embodiments of America’s demographic divide and market capitalism’s attempt to please (and profit from) the greatest number anyway.

The 21st century’s story, of course, is getting memorialized as it happens, and knowingly or subconsciously staged beforehand (with the screens in our hands), so the fact-finding (or as Peterson’s character would have it, feeling-finding) of the reporters is like a Citizen Kane that references itself as it unfolds, a mirror held up to another mirror.

Almost every time someone speaks in the play’s first section it’s like an Oscar-bait grand gesture (Zuri Washington, as the “Home Town Girl” Our Boy left behind, is particularly skilled at these soap-operatic soliloquies), because these days we’re nobody’s constituents but everybody has their own audience. And their own soundtrack; when Alyssa Simon as one of Our Boy’s Moms fleetingly cracks the shell of her suburban composure to address her anxieties to the fourth wall, she’s validated in opening up by “the gentle acoustic guitar music” that starts playing behind her; in the Spotify decade this is scarcely even a joke.

Amir radiates amiable Dan Quayle brainlessness, and Rishawn magnanimously nondescript Fred Thompson confidence, as Our Boy, and when questioned what was special about him(s) in school, his own parents “remember more how people said he made them feel than how he did it.” But CANT, um, can’t be about forgetting the past and repeating anything, because the ascendant demagoguery being dramatized is without precedent. This is a play and cast (and one could now argue, a country) that has a memory of everything, just no ability to process any of it.

Thoughts collide like Trump’s bizarre free-associative skim of both privileged and proletarian grievances (xenophobic bigotry; outsourcing/offshoring anxiety) in character names like “Uncle Samuel French,” a splice of our national male symbol, and a leading theatrical publisher, and Miss Liberty’s country of origin and, when at one point he’s called “Mr. French,” the butler on a forgotten family sitcom of the 1960s. (Our Boy’s living-room roots, returned to at many points in the story, are the nexus of TV-enthralled midcentury American life, in this case looked into rather than out of.) Periods overlap like mass broadcast hallucinations, as when a high-society soiree setpiece straight from a Fred & Ginger flick shifts seamlessly to a stock gogo-freakout from counterculture exploitation movies (as always, Hill’s eye for these visual languages and tech mastermind Berit Johnson’s light and sound environments are supernaturally spot-on).

The collective media unconscious is one of endless content and diminishing context, and the play’s first section, like the electorate, reflects this with an air of anxiety that has no shape and no container. Comprehending some compacted version of the national dilemma gives a calming feeling of control, though with no “consensus” media still extant, everyone is sure of something completely different than anyone else.

The 2016 political season was especially replete with smartest-person-in-the-room proclamations — Trump knew “more than the generals”; fans of status-quo candidates on both sides knew “how the world really works”; Bernie loyalists still “know” what would’ve happened differently and Hilary diehards “know” what couldn’t have. A refrain throughout CANT, from Peterson’s character admonishing one political operative or old Our Boy acquaintance after another, is “You just don’t get it, do you?!” — both a call to the emotional intelligence that many say wasn’t marshaled in the recent campaign, and an assertion of simple yet secret, special knowledge. Anyway, almost all of us are gonna get it now.

As Our Boy’s chronically overlooked Sister, Anna Stefanic gives an impassioned speech toward the end of the first act about how, despite her safe social status, she is going to dedicate herself to the dispossessed; very movingly articulated at first, clichés creep in to undermine her own oratory and then self-congratulation takes it over completely; in time, however staunch an “ally,” every privileged American moves toward the spotlight. More cooperatively, the act ends on a group rendition of Prince’s socially-awake spiritual “Avalanche”; CANT feels like a civic church service of sorts, so this is an apt note to leave off on.

Not by accident is the song delivered by all (and only) the show’s black cast members; our house divides along a faultline from slavery centuries ago to the election of a white-nationalist collaborator last week, and the play argues with itself over its racial balance and realism. As the house figuratively caves in and the actors try and escape with their identities, Rishawn and Washington as well as Leila Okafor (the click-bait mogul pressuring the two reporters) and Rolls Andre (one of Our Boys’ two hapless sitcom dads) appear as themselves to critique black images here and elsewhere, in a couch-and-fern setup evoking public-affairs programming from the graveyard timeslots of bygone broadcast TV. At another point, Rishawn delivers an incisive monologue about typecasting, ostracism and capitulation for all would-be pathbreakers, while everyone else in the cast drains off the stage like bored highschoolers at an unwelcome assembly.

The play’s narrative gravity carries it through a checklist of demagoguery, repression and insurgency, and leaves the rechristened “Chairman Boy” on a shaky pedestal (tellingly, whereas his ascent is mostly true to vintage media templates, the comparatively short revolutionary section feels chillingly true to life, if oddly detached from consequence). Then the play discards its electoral allegory to at first seemingly turn into a burlesque of postmodern self-reference and observer/character paradoxes — which it does with great invention and wit — but a more encompassing metaphor wells up around the actors anyway, as their meta attempts to resist the dictates of the script point up how we all operate under the tyranny of what we’re told. This is literal with a control-voice and -face manipulating or outright commanding the action (Lex Friedman and Rebecca Gray Davis hilariously stern as two judgmental A.I.s). It’s figurative in the fear that our context sets terms of consciousness that we can’t be capable of conceiving beyond. Fourteen actors searching for how to break character comprise an intriguing parable about how to see out of the personal fog we all can sometimes carry within the wider social wilderness.

Whether phasing in or out of fantasy, the whole cast is note-perfect in its absurdist craft and Fisher-Price schoolbus collection of personae. Bachrach is poignantly buffoonish as Our Boy’s overconfident teacher turned deranged prophet. LaPergola and Andre are master clowns, LaPergola with her baroque toughgirl attitude and florid dismay, and Andre with his fragile authority and hair-trigger chagrin; LaPergola’s post-Lucille Ball grimace grin and Andre’s rapidly-deflated-balloon reaction-time and tone are priceless reminders of what’s so funny, even in days like these. Linus Gelber is artisanally silly as Our Boy’s cheery and self-deluding other Dad. Washington is ingeniously invested in her melodrama; Okafor majestically imperious and insecure. Cullinan as Our Boy’s contentedly narrow-minded other teacher, and Olivia Baseman as the femme fatale of someone else’s story, are each iconic figures uncooperative with their stereotypes. Stefanic is composed yet flammable as the fragmented First Family’s household revolutionary (and typically brilliant in her piano playing, though these characters’ scant use for a Greek Chorus puts a stop to that pretty soon). Hill himself is gone fast but not possibly forgotten as he pulls off an odd hybrid of Captain Ahab and Sandman Sims. Peterson maintains a Hunter S. Thompson level of uncontextual gravitas and paranoid self-importance, and Alyssa Simon finds yet another shade in the troubled, volatile Stepford-mom characters she handles with such humor and melancholy.

CANT was written before, but premiered after, the many jokes it makes so well got to their real-life punchline, and now the play is a steak for every eye. At one point someone describes Our Boy’s childhood environment as an idyll of “parks, libraries, beaches and schools” — a kind of dream composite of every comfort Americans seek. We can’t really have it all in one place (or one personage), but Hill and his collaborators are at work on widening a frame that we all can find space, and maybe even each other in.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE