America Obscura (2)

By:

November 12, 2016

HILOBROW friend Andrew Hultkrans is a legendary freelance journalist; we have admired his range, erudition, and virtuosity since the early ’90s, when he was a columnist at MONDO 2000. We’re proud to publish this series of essays by Andrew, each of which originally appeared (as noted) elsewhere.

Here’s Looking at You, Kid: Surveillance in Cinema

The recent furor over Lexis-Nexis’s P-Trak Person Locator Service reminds us yet again of our periodic collective amnesia regarding the inexorable encroachment of digital surveillance. In an era when, as many techno-cultural theorists have argued, each individual is shadowed by a virtual body double comprised of credit histories, medical records, criminal rap sheets, and demographic profiles, it is astonishing that a service like P-Trak—which, while fiendishly convenient, offers no more information than a novice Phillip Marlowe could gather with a few phone calls—still has the ability to inspire moral outrage. Consumers clamor for more ATM machines, more point-of-purchase payment options, more smart cards, more digital cash, more online shopping, all while simultaneously decrying the invasion of privacy intrinsically connected to such conveniences—that is, whenever a news story refreshes their memory.

Overnight civil libertarians are fond of flogging the Orwell warhorse “Big Brother is Watching You” while fuming on talk radio, failing to note that they have been watching Big Brother watching us for decades on the funhouse mirror of Hollywood cinema. Since its birth, but most evidently since the 1950s, cinema has played with surveillance, voyeurism, and the power of the gaze, often in cautionary tales that conjure the specter of totalitarianism, and also through meta-references to the movie camera’s own complicity with institutional voyeurism. The godfather of all surveillance films is Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), an oft-quoted movie which masterfully explores the director’s parallel obsessions with voyeurism and film. The credit sequence opens with the raising of James Stewart’s window shades—multiple theater curtains that will reveal a multiplex of unfolding “movies” in the apartments across the way. Stewart, a top-notch magazine photographer, has had his camera and, more importantly, his leg, broken while on the job, virtually emasculating him and casting him in the passive role of the spectator, a truly captive audience.

In the course of his ostensibly innocent “peeping” into his neighbors’ lives, he becomes convinced that there is a murder plot unfolding in one of the “screens” on the opposite building. Scolding him for his voyeurism, his masseuse observes, “We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms—what people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.” Deprived of physical agency, this is precisely what Stewart cannot do, as he is doomed to watch helplessly as longtime noir heavy Raymond Burr disposes of his wife, piece by piece. Like a filmgoer, Stewart is powerless to affect the scene commanding his field of vision, yet just as the filmgoer sutures himself into the narrative by identifying with the protagonist, Stewart is fooled by his “God’s-eye view” into believing he can alter the course of the “murder movie” playing itself out across the lot. Enter a great pair of legs, in the shape of Grace Kelly, who, in gaining her own agency, acts as Stewart’s proxy in foiling Burr. Along the way, Stewart breaks his other leg but succeeds in both healing his fraying attachment to Kelly and curing his scopophilic urge as his window shades are drawn shut at the end of the film.

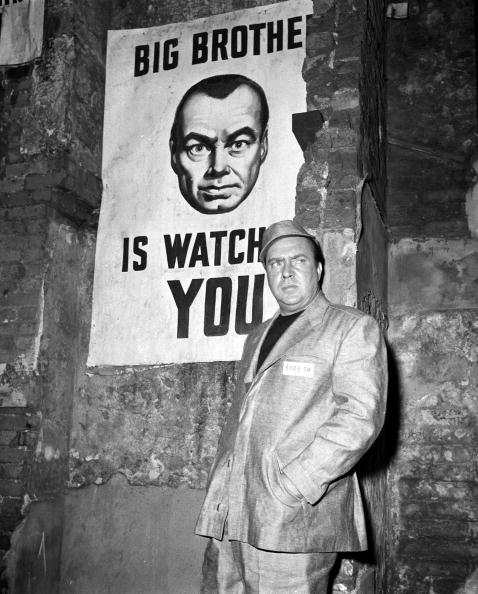

While Rear Window addresses the neurotic need to surveil, the two film versions of George Orwell’s surveillance nightmare 1984 (1956, 1984) explore the collective insanity and absurd paradoxes induced by constant panoptic observation. As Michel Foucault argued in Discipline and Punish, the key to the absolute hegemony of Big Brother is not that “he” is actually watching you at all times (in fact, there is no “he” at all), but that, as in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison, you come to believe he may be watching at you any time, hence you police yourself. The omnipresent visage of Big Brother and his telescreen “eyes” serve as constant reminders of the carceral, fascist atmosphere that permeates Oceania, a prison not of bars, but of the mind. Terry Gilliam’s mordant, retrofuturist masterpiece Brazil (1985) can be considered another remake of 1984, one that pointedly demonstrates—in the Buttle-Tuttle glitch that sets the plot in motion—the hazards of misidentification inherent in massive databases of personal information.

The specter of the fascist mastermind is resurrected in Fritz Lang’s third and final Dr. Mabuse film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), in which a criminal madman adopts the persona of the diabolical Dr. Mabuse, an ubergodfather and master of disguise who died in the first Mabuse film but whose megalomaniac spirit still haunts the German unconscious. Given a postwar spin, the new Mabuse operates a sophisticated surveillance system from within his sanctum in the bowels of the Hotel Luxor, the site of the several “movies” within the film itself. From this command center, Mabuse observes all of the hotel rooms on a bank of video monitors (the “thousand eyes” are microcameras hidden in the moldings of the rooms) while performing two manipulative roles in the outside world: as Cornelius, a blind “seer” who aids the police in “solving” his own crimes, and as a psychiatrist who runs a high-end sanitarium. Ironically, Mabuse is exposed by his (Cornelius’s) own seeing-eye dog, who runs to him as he tries to escape the lobby of the hotel in a final disguise.

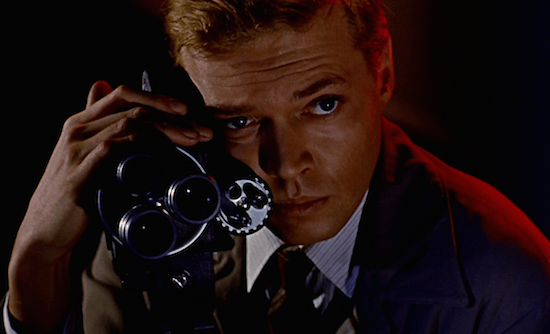

The theme of obsessive scopophilia is revisited in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), perhaps the finest word on the subject. A dark, hysterical film, Peeping Tom examines the madness resulting from a childhood under extreme surveillance. Mark, a shy cameraman, was raised by his biologist father as an experiment and subjected to the constant recording of his experiences, most of which, given his father’s primary interest, dealt with his responses to fear. As a grown man, Mark has become a meta-murderer. Not satisfied with the experience of murder itself, he feels compelled to film not only his victims as he stabs them with a knife-fitted tripod leg, but also the resulting police investigations—when questioned about his filming at the scenes of his crimes, he replies that he is reporting for The Observer, a local paper. Echoing his father’s experiments, Mark has also fitted a mirror onto his camera so his victims will be able to see their own mortal fear as they die. At the end of the film, he turns this apparatus on himself, impaling his own body on the customized camera as preset still cameras snap the scene, a fitting end to a relentlessly recorded life.

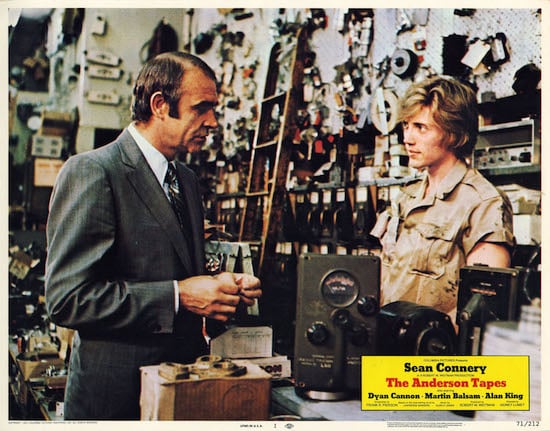

In the 1970s, independent investigations of the JFK assassination and mounting Watergate revelations exposed the web of geopolitical surveillance penetrating everyday life, resulting in a series of paranoid films populated by spooks, double agents, CIAs within CIAs, and, primarily, miles and miles of recorded media. Sidney Lumet’s The Anderson Tapes (1971) neatly expresses the emergence of a virtual body double shadowing even the most mundane individuals. The film is composed of two narratives arbitrarily connected by surveillance: one is a routine heist caper in the mode of The Asphalt Jungle (1950), the other, a surveillance conspiracy in reverse. Sean Connery, an ex-con planning the heist, unwittingly weaves together a disparate group of surveillance operations—government, police, bedroom dicks—by being taped by all of them while in contact with their primary targets. When the heist is foiled, and Connery’s character’s name is broadcast by the news, all of the agencies, public and private, erase their tapes to avoid exposure. A bleak parable confirming the paranoiac’s worst fears, The Anderson Tapes was a harbinger of the Watergate scandal about to break. Like Connery’s heist, Nixon’s Waterloo would expose a series of covert surveillance operations to public inspection.

Projecting the grim surveillance state of 1984 into the distant future, George Lucas’s THX 1138 (1971) presents an oppressively white, dystopian Habitrail under surveillance at the cellular level. All citizens have numbers instead of names; they are sedated by a cocktail of drugs by law; sex is taboo; and their labor is monitored by biochemical scanners that detect even subtle signs of illegal “sedation depletion.” Augmenting the State’s complete penetration of its citizens’ lives are mechanized confession booths, which record potentially incriminating admissions while droning prerecorded sympathies and disturbing homilies: “Let us be thankful we have commerce. Buy more now.” Friendly fascist robocops complete the picture in this nightmare of total exposure.

Echoing Rear Window, this time for audiophiles, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) follows a lonely surveillance expert as he slowly becomes embroiled in a murder conspiracy he has recorded for hire. Unlike the perversely curious Stewart, Gene Hackman has no interest in the content or results of his surveillance efforts before recording the titular conversation. “I don’t care what they’re talking about; all I want is a nice fat recording,” he tells his assistant. The more he begins to care about the events set into motion by the conversation, transforming himself from a recording device into a human being, the more he finds himself—already a paranoiac—under surveillance. Like Stewart, he is impotent, unable to prevent the crime he knows is taking place, yet unlike Stewart, he has no surrogate “legs” to act for him. He vicariously witnesses the murder and, already terrorized by guilt, learns that he will be forever spied on to ensure his silence. The film ends with Hackman literally gutting his apartment as he searches unsuccessfully for the bugging device, a hollow man inside a hollow shell—“a bug under a glass,” as Stewart observes of his own confinement.

A black humor pastiche of 1970s conspiracy narratives, William Richert’s Winter Kills (1979) expands the thousand eyes of Lang’s Mabuse to a global surveillance citadel that absorbs “black holes of information, galaxies within galaxies of information, multiple expanding universes of information” for billionaire industrialist John Huston. Overseen by a sinister Anthony Perkins, this omniscient techno-castle mimics every aspect of human perception on a global scale, with divisions for video, audio, memory, and an enormous “contract silo” containing holographic signatures of everybody who’s anybody in world affairs. “All of the nerves and none of the flesh,” a proud Perkins explains, “even tonight when most of our workers sleep, it goes on.” Impossibly overreaching in scope, the surveillance citadel of Winter Kills is the last word on 1970s-style geopolitical observation.

Marrying the conspiracy narrative to voyeurism, Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981) conflates Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and The Conversation, offering John Travolta as a schlock horror sound man who inadvertently records the assassination of a presidential candidate in the form of an auto “accident.” Like Stewart in Rear Window, his attempts to alert the authorities to the plot are met with scorn, and like Hackman, he is unable to prevent the crime (or the murder of his love interest) and ends up a hollow man, his only consolation the recording of his lover’s death screech, which he dubs into a horror film that needs a more “authentic” scream.

In Body Double (1984), De Palma boldly lifts elements from Hitchcock, as he is wont to do, simultaneously remaking Rear Window and Vertigo (1958). The film follows Jake Scully, a claustrophobic, out-of-work actor who becomes the unwitting planned witness to a murder. The murderer, a man intending to kill his wife, poses as an actor and offers Scully a chance to stay at a spectacular circular house with a 360-degree view of L.A. below. The house is conveniently outfitted with a telescope trained on the window of an attractive woman’s apartment down the hill, a woman who “like clockwork” performs a masturbatory striptease every night. An obvious voyeur, Scully, as planned, watches the woman’s apartment regularly, eventually witnessing her grisly murder at the hands of an evil Native American wielding an industrial power drill. De Palma piles on the cinema = voyeurism subtexts by having Scully descend into the bowels of the porn industry to discover the “body double” hired by the killer to do the nightly striptease.

A decade later, De Palma’s excesses in overdetermined metaphor are outdone a thousandfold by Joe Eszterhas and Phillip Noyce in their tepid steambath of a surveillance film, Sliver (1993). Fresh from her crotch-flashing turn as a femme fatale in Eszterhas’s Basic Instinct (1992), Sharon Stone plays a woman who moves into a hypermodern glass “sliver” building in Manhattan, because she “loves the view.” Unbeknownst to her, she strongly resembles the former tenant of her apartment, a woman who mysteriously plunged to her death from the balcony. During her first few days in the building she meets some of her neighbors, a professor teaching a class on “The Psychology of the Lens” at NYU; an opera-glass-carrying true-crime writer who boasts “You’ll read me” and “I am in control”; and a mysterious young man, ultimately revealed as a harmless version of Mabuse and Mark of Peeping Tom, who sends Stone a telescope signed “Your secret admirer.”

The suave young man, played by William Baldwin, is a computer game programmer whose relationship with his mother was highly mediated; she was a soap-opera star whom he saw only on TV. Like Mark, he has grown up suffering from obsessive scopophilia, and like Mabuse, he is the manager of a building whose every room is wired, feeding the tenants’ lives into his inner sanctum. Stone repeatedly sleeps with Baldwin, and a number of other murders take place in the building, in which Baldwin (the Mabusesque video addict) and Tom Berenger (the impotent, embittered crime writer) are prime suspects. Berenger turns out to be the killer, but Stone discovers that Baldwin is as addicted to seduction as he is to watching, having previously landed both victims of Berenger’s handiwork with the same “I want to see you” rap. Shooting out his array of video monitors with a gun, she spurns Baldwin, telling him to “get a life” as she clicks off the film itself with his remote.

In The Anderson Tapes, The Conversation, and Blow Out, recorded media capture incontrovertible evidence of criminal conspiracies that must be erased to be nullified; in Philip Kaufman’s Rising Sun (1993), recorded evidence becomes highly mutable, a valuable tool for conspirators. A sex murder recorded to a “next-generation” videodisc by surveillance cameras becomes the centerpiece for a labyrinthine (and race-baiting) plot involving a controversial Japanese buyout of an American software company that produces high-end military applications. The original videodisc is digitally doctored by rogue elements in the Japanese corporation—erasing a person from the frame, eliminating a stretch of time, and pasting an innocent man’s face onto a guilty one—and then delivered to the police. With the help of a digital media expert played, naturally, by Tia Carrere, the missing information is restored, the conspirators are exposed, and American software remains where it belongs, in the hands of the Pentagon.

Through the work of Atom Egoyan, a Canadian director obsessed with mediated video experience and voyeurism, and a dubious new genre, the cyber-thriller, cinema’s love affair with surveillance continues unabated. So too does the periodic public outcry over new real-world snooping technologies, followed by periods of utter complacency in the face of the expanding surveillance state. One must be ever vigilant, for, as Inside Edition reminds us every night, “America Is Watching.”

Originally published by the web magazine STIM, November 1996.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators