THIS: Artsploitation

By:

November 7, 2016

To be reborn, you have to die…or at least one you does. Hero’s Journey narratives are often about the remaking of a personality; the phoenix-like transformation of the person you were, or discarding of the less authentic persona you wore. For the dispossessed, this is more than metaphorical. As Jews were getting exterminated in the 1930s, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby (née Kurtzberg) created their champion, Captain America, as a kind of secular Adam, formed not by the God that Jews may have felt abandoned them (and whom many at that time in history had already abandoned themselves), but by the science people still placed their trust in; a perfect specimen meant to be the first of his kind and then (with the death of the scientist and his secrets) condemned to fully connect with the rest of humanity only as an example. If he prevailed, others joined the call, and some lived on.

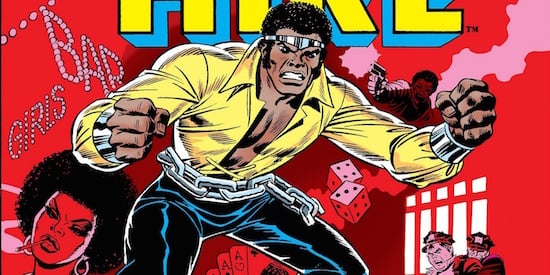

By 1972, the modern Civil Rights movement in America had been largely murdered out of existence; assassination for Evers, X, and King; summary executions of Panthers by national and local law enforcement; extrajudicial killings of activists and apolitical, scapegoated (second-class) citizens alike. Luke Cage, the first Black superhero to be featured in his own solo book, was literally created in a crucible; a weird chemical mix into which Black prisoners were dumped by an experimenter and which only Cage survived (with inescapable echoes of the Tuskegee atrocity, though Cage’s comic debuted four months before that study was first widely exposed). He too remains the only one of his kind, a symbol with a weight on his shoulders even heavier than the collapsing buildings he can hold overhead. If the movement for Black personhood was to survive, it had to be reborn; the spirit of its stricken standard-bearers distributed to successive generations. Carl Lucas literally dies in his chemical vat; walks back out of Hell by escaping the prison. That is, “Luke Cage” emerges, his past self left behind. A paragon who has that past self’s memories, but is re-created in a new image, both more powerful and more protective.

Well, not exactly a paragon at first. While we were always meant to identify with and root for Cage in his original comicbook incarnation, as a renegade from the social strictures, systemic unfairness and untrustable government of the times, he started as a “Hero for Hire,” modeled on the Blaxploitation protagonists of contemporaneous cinema and prefiguring the mercenary, materialistic gangsta-rap personae of later decades. Like most of those movies, early (and many later) Cage comics were more often than not as stereotypical as they were affirmative. The thrill of any mass-media representation at all for viewers and readers of color in those times often outweighed the embarrassment that everyone could feel over the level of understanding at which these characters were portrayed. (The calculus was similar for Jewish kids like me, trained to see what wasn’t in the picture, and even for some Anglo-Saxons uncomfortable with their legacy — also me — though of course the stakes were not equivalent.) There’s a tortured balance of baby and bathwater; the 1970s in America were another renaissance of Black culture, in which self-expression reached one of its peaks; political expression remained repressed, and exploitation cinema and related pop processed rebellion into pastime and kept caricatures reinforced. So, Luke Cage hasn’t just survived the bloody suppression of the 1960s Civil Rights movement, or his own ordeal; the much more naturalistic and dimensional character he is today has survived the conflicted cultural context of his own creation.

This hero has gone through several faces — the tragically unhip enforcer of the early 1970s (always written by white males, sometimes drawn by Black artists); the neutral, workaday superhero of the later ’70s to ’90s (briefly replacing Ben Grimm in the Fantastic Four, teaming up for long-running and well-received adventures with millionaire martial artist Iron Fist); the gangsta incarnation of the early aughts and the grassroots leader and empowering populist protector of today.

He metamorphosed, of course, into something even more real with the milestone Marvel/Netflix series. This Luke Cage has the disciplined defiance of the Nation under Malcolm; the contained umbrage of Kendrick and other artisans of self-evident truths; the eloquence of Jesse Williams in voicing what’s best in us and what’s broken between. As Cage, Mike Colter’s physical presence is the unbowed Black body (and body politic) from Jack Johnson to Colin Kaepernick (the sights of the upper-Manhattan landscape projected onto his form in the opening credits are like both a social scar and a sacred marking); his heartfelt, aspirational speeches the kind of terms we long to hear and assent to. (The latter can not be underestimated; public speech is the actualizing scripture of democracy, set forth by Douglass, and King, and Obama; it’s no accident that the Captain America character in both comics and current movies has heart-stirring address as one of his superpowers, and no coincidence when an enemy in the Luke Cage series derides Luke as “the Captain America of Harlem”; villains and dictators can issue commands that make the masses run away, but oratory like Cage’s speeches at Pop’s funeral and in the precinct house at the end are what push them forward.)

“Everyone has a gun, but no one has a father,” Cage ruefully remarks at one point to his own surrogate father-figure Pop, and Luke aspires to be an example to his community like Pop has been to him. But most business is really taken care of, and social structures held together, by mothers, daughters and sisters in this show; it may be the most matriarchal series or movie Marvel has done yet (by proportion of strong and pivotal female cast members, perhaps even including Jessica Jones and Agent Carter). The unshakably caring, badass agent of mercy Claire Temple (Rosario Dawson); the steely and forbearing Inspector Ridley (Karen Pittman); the positive, persevering Patricia (Cassandra Freeman) and tragically principled Candace (Deborah Ayorinde); the undefeatable local businesswoman Connie, played by Jade Wu (the haters who took to Twitter to whine about the show’s perceived shortage of white characters of course didn’t catch the subtlety and intricacy with which this show addresses relations between Black, Asian and Latin communities); the fearsome, formidable and murderously scarred political power-broker Mariah (Emmy material from Alfre Woodard); the empowering yet emotionally elusive psychologist (and Luke’s lost love, in more ways than one) Reva Connors (Parisa Fitz-Henley); and the proud, damaged, visionary, flawed, tender, heroic detective Misty Knight (Simone Missick, in one of the series’ profound character-studies on the spectrum of how much we let or refuse bad experiences make us into bad people). The African-American family was put under siege from the first child sold from his or her mother at a slave auction, and this series is about those failing and succeeding to unbreak it. The tenderness and perseverance, as well as bitterness and need, of the show’s many frayed ties and family secrets, is approached with rare unblinking empathy by series creator Cheo Hodari Coker and his collaborators. And from the intimate to the society-wide, the sense of accumulated heritage, rather than compounded cliché, is palpable in this on-location epic of everyday life-force in the stylish entertainment-palaces and sheltering shops and august brownstones of legendary African cultural capital Harlem. I’m not saying it had to take a mostly Black creative team to get this right, but apparently, it did.

In that, the series presents a path for confrontational yet less compromised issues-pop. A Quentin Tarantino regularly risks adulteration by the very stereotypes and social crimes he’s diving into, and I’ve usually felt the shock-therapy is worth it in a largely silenced society patrolled by the privileged. But is there a way to not play with the fire of bigotry but the light of potential, of legacy? Luke Cage proves that there is — and this too is not accidental; an African-American showrunner and staff may be less aloof about reopening wounds rather than treating them; and repair from trauma is central to this story — one of the main heroines is a nurse, Luke is externally impervious but deeply injured inside, and unaddressed tragedy drives most of the villains, many of whom seem not to have started that way. Luke Cage moves on from atrocity, but does not run past it; the show is not emptily “affirmational,” it’s insistent, and thus as badass and brave in its way (and perhaps more lasting in its effect) than many a Tarantino or Robert Rodrigues or Larry Clark film (though each is valid).

One of my teachers, Amiri Baraka, once referred to an abruptly abusive literary character’s “Mr. Hyde masculinity”; and that negative is fully visible and unvarnished here. The tortured Shakespearian grievances of Stokes (Mahershala Ali) and Stryker (Erik LaRay Harvey) as they seek conquest and coerced adulation as a remedy to the indifference they were shown in youth; the psychotic self-acceptance (’cuz, who’s stopping him?) of the sadistic Shades (Theo Rossi); the losing battles with greed and exploitative hubris inside corrupt cop Scarfe (Frank Whaley) and prison scientist Burstein (Michael Kostroff); the hard-won benevolence of Pop (Frankie Faison) and Squabbles (Craig Mums Grant), two men who have turned from destructive pasts to nurturing, tenaciously serene mentor missions — across race and class, choices are made but the same line is walked by all the males; we are shown both sides, and inside the story, some, like Luke, can see across it. In common with many superheroes, Luke Cage is a figure of hypermasculinity, but he knows this is a lot different than manhood, and as a real-life patriarch runs to be dictator of the world, this is an important reminder to get. (Though the poison of authority and the destructiveness of the renegade are wrestled with across the entire cast of criminal potentates, embattled cops, would-be saviors and conflicted vigilantes, male and female alike, with an equal clarity about the characters’ motivations and their decisions’ consequences.)

Reading recent Cage-driven comics like Mighty Avengers (in which Luke leads a storefront franchise of the team to protect everyday citizens), and watching the Luke Cage show, I feel like I’m back in an era (I predate Luke’s first comic) that lifted spirits and raised a voice — the assertion and contesting of an inclusive, expansive worldview and family of humanity. A time so far behind us that it seems like a dream — and which, to witness the open hatred emboldened in America’s waning majority by its current demagogue and the social divisions which have persisted or resurfaced, probably always was no more than that. Which could mean it still just lies ahead of us, and for once might not have to die before it comes true.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE