10 Best Adventures of 1961

By:

September 15, 2016

Fifty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Fifties Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any 1961 adventures that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- William Burroughs’s sci-fi adventure The Soft Machine (revised, 1966 and 1968). To the extent that The Soft Machine — first installment in the author’s Nova Trilogy — has a plot, it is something along these lines: Using a time travel device, an agent who is able to transform his body (using “U.T.,” undifferentiated tissue) causes the downfall of the ancient Mayan empire. How? He infiltrates the Mayan slave laborers, who are mind-controlled by sounds recorded on magnetic tape — by the priestly caste — and embedded in books (the famous Mayan calendar). The agent replaces the tape with one broadcasting a revolutionary message, “Burn the books, kill the priests.” The theme of Burroughs’s experimentalist novel, which was composed using his notorious “cut-up” technique, is how fascist control mechanisms invade and regulate the body — the titular soft machine. In addition to time travel, The Soft Machine circles around themes of media bombardment, sexuality, and out-of-body travel. According to Burroughs: “I am attempting to create a new mythology for the space age.” Fun fact: The Soft Machine was first published by Olympia Press, in Paris, as part of their infamous, mostly pornographic Traveller’s Companion Series.

- Stanislaw Lem’s sci-fi adventure Powrót z gwiazd (Return from the Stars). Returning from a 10-year mission, astronaut Hal Bregg returns to Earth — where nearly 130 years have passed, due to time dilation. He and the other astronauts discover a global utopian social order free not only of violence (thanks to “betrization,” a biochemical procedure that neutralizes aggressive impulses), but even car crashes (thanks to Google Self Driving Car-like tech). Physical risk-taking has been eliminated… but has the cost been too high? Bregg can’t adapt — he’s a monstrous figure, an anachronism. (Hello, Demolition Man.) Space exploration is now seen as youthful adventurism, too dangerous to continue. Earth, to him, is no longer home, but “another, alien planet.” Will Bregg settle down and accept this pacified existence, or join his fellow astronauts on a new space mission? Fun fact: One suspects that Lem was influenced by Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Radium Age sci-fi parable The Bedbug (1929). PS: Return from the Stars predicts e-readers: “No longer was it possible to browse among shelves, to weigh volumes in hand, to feel their heft, the promise of ponderous reading. The bookstore resembled, instead, an electronic laboratory. The books were crystals with recorded contents. They can be read with the aid of an opton, which was similar to a book but had only one page between the covers. At a touch, successive pages of the text appeared on it.”

- Elmore Leonard’s revisionist Western adventure Hombre. The narrator of this novella, the prolific author’s fifth Western (but first really good one), is a timid librarian who finds himself traveling by stagecoach with five others, including the infamous John Russell, a white man who’d been raised by Apaches and now works as a tribal police officer on their reservation. Another passenger is a government Indian Affairs agent whose greed has left the Apaches half-starving… and who is carrying the money he has embezzled. Russell is shunned by the bigoted passengers, until the stagecoach is robbed, and a female passenger kidnapped. (This is an ironic turn of events, as the woman — the wife of the shady Indian Affairs agent — had declared, earlier, that only Apaches kidnap women; the stagecoach robbers are white.) Now it’s up to Russell to lead the group to safety across the Arizonan wilderness. Fun fact: Hombre was adapted, more or less faithfully, as a 1967 movie directed by Martin Ritt. Paul Newman played the title character. Elmore Leonard stopped writing for nearly a decade, after Hombre was published; he then resurfaced as a crime novelist.

- Robert Heinlein’s sci-fi adventure Stranger in a Strange Land. One of the most famous, and most infuriating science fiction books ever. Its premise is a promising one: Valentine Michael Smith, a human raised by cosmically wise Martians and endowed with psychic and telekinetic powers, is brought back to Earth — whose social, cultural, economic, sexual, and psychological customs he finds bewildering and strange. With the aid of Jubal Harshaw, a Socrates-like philosopher, physician, lawyer, and sybarite, Smith becomes a controversial champion of free love, open-mindedness, and pacifism. He’s a Martian Jesus, and the father of a new race of homo superior types; Jubal — a transparent stand-in for Heinlein himself — is his John the Baptist. The book became a cult hit later in the Sixties, for obvious reasons; however, it is firmly anchored in Fifties culture too. Despite its charms, Stranger in a Strange Land is often tedious (Jubal, taking his Socrates/JtB-like role seriously, pontificates endlessly); and — worse — it is shockingly, pointlessly, outrageously misogynistic and homophobic. That said, even critics tend to like the book’s ending. Fun fact: Stranger in a Strange Land, which in 1962 won science fiction’s Hugo Award for Best Novel, and which was the first sci-fi novel to enter The New York Times Book Review‘s best-seller list, gave us the word grok — meaning, like, “comprehend thoroughly and have empathy with.”

- Harry Harrison’s sci-fi/crime adventure The Stainless Steel Rat (serialized 1957 and 1960; as a book, 1961). In this, the first-published Stainless Steel Rat novel, the title character — ingenious and multitalented conman, smuggler, and thief James Bolivar diGriz, who our of sheer boredom refuses to internalize the complacency of the settled, end-of-history galaxy in which he finds himself — is conned into helping a secret government agency unravel a nefarious scheme for manufacturing a galactic-class battleship. The Rat falls in love with the master criminal — a beautiful, but sociopathic woman — and tries to reform her. (If the plot sounds similar to Leslie Charteris’s 1931 Saint adventure, She Was a Lady, perhaps it’s because Harrison was a Saint fan; in fact, in 1964 he ghost-wrote Charteris’s Vendetta for the Saint.) Much like Heinlein’s Stranger In a Strange Land, this novel is progressive and fun — Fifties-type political, cultural, and social norms are for losers! — while also disturbingly retrogressive. The brilliant, independent female character is a sociopath, it turns out, because… she was born unattractive. Yeesh. Still, without Slippery Jim, would we have the charming rogue Han Solo? Fun fact: Harrison was originally a cartoonist for the EC titles Weird Fantasy and Weird Science; the great Wally Wood often inked his layouts. Large sections of The Stainless Steel Rat first appeared in Astounding as novelettes. Chronologically, this is the fourth title in the series.

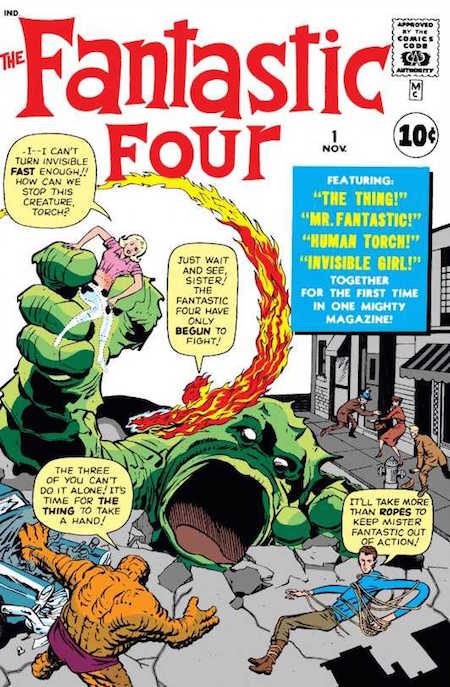

- Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s superhero comic The Fantastic Four. The so-called Marvel Age of comics began in November 1961, with the publication of Marvel’s first superhero team title, The Fantastic Four. Just a few months after Yuri Gagarin’s pioneering spaceflight, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby dreamed up a team of unofficial astronauts — genius scientist Reed Richards, siblings Sue and Johnny Storm, and pilot Ben Grimm — who sneak into space in a rocket of Richards’s own design. Bombarded by cosmic rays, the quarrelsome crew are transformed: Sue can turn invisible, Ben’s body is scaly and powerful, Johnny can burst into flame and fly, Reed can stretch himself into any shape. In their first outing, the Fantastic Four jet to Monster Isle, the source of subterranean attacks on atomic plants around the world. There, they discover that the Mole Man, who seeks revenge on humankind for having ridiculed him, plans to invade the surface world with an army of monsters! Fun fact: Lee and Kirby upended the superhero conventions of previous eras by eschewing secret identities, and allowing their characters to have real-life problems and interpersonal conflicts. In the first few issues of Fantastic Four (the “The” was dropped in July 1963), the team doesn’t even wear uniforms.

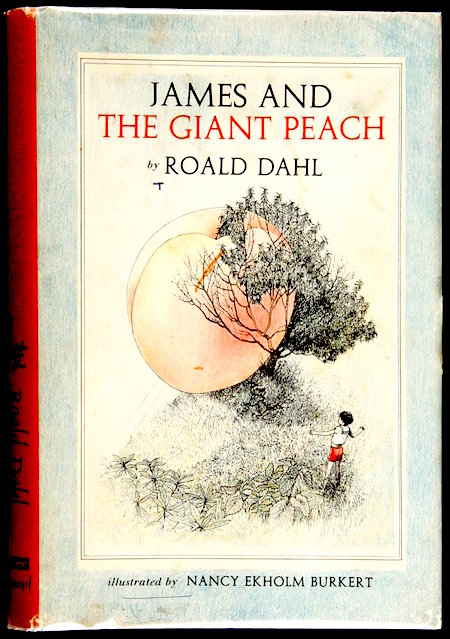

- Roald Dahl’s children’s adventure James and the Giant Peach. Both crazy book-banners and Roald Dahl fans like to hate on James and the Giant Peach — the former, because the book promotes disobedience and celebrates communalist living; the latter, because as fables go it’s pointless and silly. All of these are reasons to enjoy the book, which I do very much. What child doesn’t love peachpits, insects and annelids, sharks, and fantasies of steamrollering cruel adults before escaping across the ocean to a better life? Forced to live with his aunts Spiker and Sponge, after his parents are killed, young James is treated as a servant until he meets a fairy-talish old man who gives him magical crocodile tongues. James spills the tongues near a barren peach tree, which produces an enormous peach — inhabited by a human-sized, talking grasshopper, centipede, earthworm, spider, ladybug, silkworm, and glow-worm. James’s knowledge and ideas are highly prizes by this motley crew, whom he helps avoid various terrible fates as they float and fly to… New York. It’s not exactly a picaresque — in fact, it’s more of a mobile Robinsonade, concerned with using ingenuity and the tools at hand in order to survive terrible threats. Like, it kinda reminds me of Roger Zelazny’s 1967 sci-fi novel Damnation Alley! Fun fact: The first edition featured beautiful illustrations by Nancy Ekholm Burkert. Quentin Blake’s illustrations are also terrific.

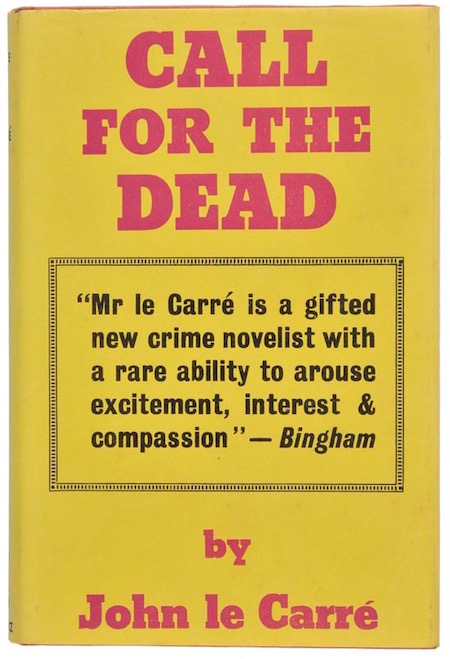

- John le Carré’s crime/espionage adventure Call for the Dead. The first George Smiley adventure is an entertaining admixture of espionage and murder mystery. Here, we meet the short, fat, badly dressed, middle-aged Smiley — an anti-James Bond, if there ever was one — and get our first inkling of what an extraordinary sleuth he is. The war has ended, his wife has run away with a Cuban racecar driver, and Smiley has wound up doing routine security checks for Maston, an unimaginative bureaucrat. When Samuel Fennan, a man Smiley has just interviewed about his wartime flirtation with communism, commits suicide, Maston berates Smiley for botching the incident. But Smiley has his suspicions. Was Fennan murdered? If so, are the East Germans involved — in particular, Smiley’s wartime comrade Dieter Frey? If so, how? Fun fact: Call for the Dead was adapted as a film, starring James Mason, in 1966. Directed by Sidney Lumet, it was titled The Deadly Affair.

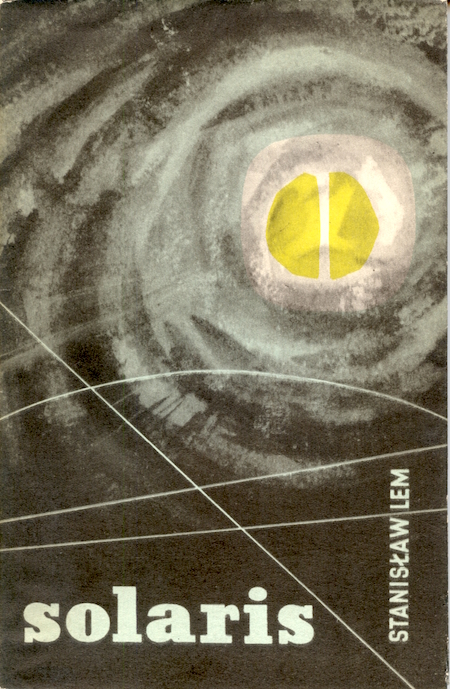

- Stanislaw Lem’s sci-fi adventure Solaris. This is a philosophical novel — at times dramatic and gripping, and at times academic and dry — asking the question, What would happen if we encountered an alien intelligence so exotic that we could in no way at all comprehend it? Psychologist Kris Kelvin arrives aboard a scientific research station hovering near the surface of the ocean-planet Solaris; this “ocean” is a chthonic organism. For decades, a team of scientists has studied Solaris’s complex wave motions and formations, but they haven’t been able to determine what these activities signify. Shortly before Kelvin’s arrival, the scientists have begun bombarding the ocean with high-energy x-rays. Apparently as a result of this experiment, the space station crew’s most painful and repressed thoughts and memories are actualized. Each member of the crew is visited by a lifelike simulacrum; Kelvin, for example, who feels guilty about the suicide of his lover, suddenly meets her again! The horrified scientists can’t bring themselves to discuss what any of this might mean; their instinctive — unscientific — reaction is to destroy the simulacra. Fun fact: Adapted in 1972, by Andrei Tarkovsky, as a gorgeous but slow-moving film — which won the Grand Prix at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival.

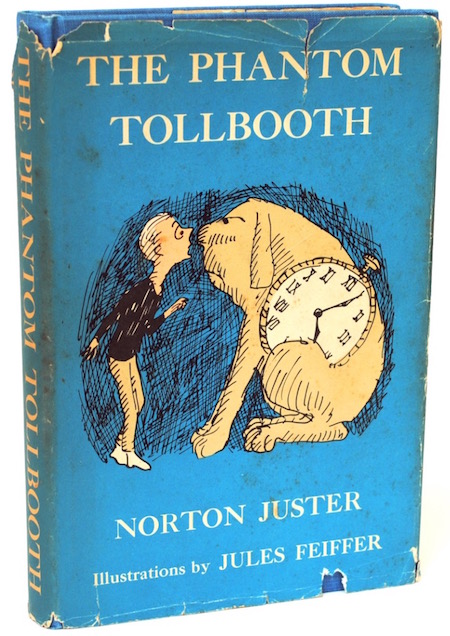

- Norton Juster’s YA fantasy adventure The Phantom Tollbooth, ill. Jules Feiffer. On the one hand, The Phantom Tollbooth is a delightful picaresque along the lines of Alice in Wonderland or The Wizard of Oz, about a boy (Milo) who explores a fantasy land in which metaphors have come to life. Milo’s companion, the Watchdog, is made of clocks; and because time flies, so can he. When Milo jumps to the Island of Conclusions, he learns a valuable lesson about the inadvisability of doing so. On the other hand, Milo learns so many valuable lessons — and the wordplay is so non-stop — that it’s a bit much. Still, who can resist? The land is ruled by the Mathemagician (who rules over the city Digitopolis), and King Azaz the Unabridged (who rules over Dictionopolis); their daughters, the princesses Rhyme and Reason, have been carried away to the Mountains of Ignorance. As he rides to their rescue, Milo encounters creatures like the Awful Dynne, the Whether Man, and Kakofonous Dischord, and learns to be more curious about and attentive to daily life. Fun fact: In 1970, the great Chuck Jones adapted The Phantom Tollbooth into a musical film. It has its moments, but it leaves much to be desired.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.