A Rogue By Compulsion (25)

By:

September 13, 2016

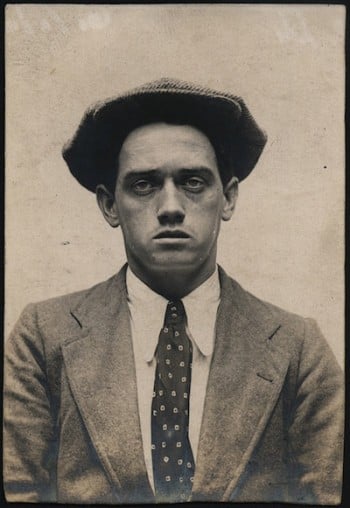

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

The moment that Sir George Frinton reached the threshold, one could see that he was seriously perturbed. He entered the room in an energetic, fussy sort of manner, and came bustling across to Lord Lammersfield, who had risen from the table to meet him. He was followed by a grey-haired, middle-aged man, who strolled in quietly, looked across at Latimer, and then threw a sharp penetrating glance at Tommy and me.

It was Lammersfield who spoke first. “I was sorry to bother you, Frinton,” he said pleasantly, “but the matter has so much to do with your department I thought you ought to be present.”

Sir George waved away the apology. “You were perfectly right, Lord Lammersfield — perfectly right. I should have come over in any case. It is an astounding story. I have been amazed — positively amazed — at Mr. Casement’s revelations. Can it be possible there is no mistake?”

“Absolutely none,” answered Latimer calmly. “Our people have moved with the utmost discretion, and we have the entire evidence in our hands.” He turned to Casement. “You have acquainted Sir George with the whole of this morning’s events?”

The quiet man nodded. “Everything,” he observed, in rather fatigued voice.

“I understand,” said the Home Secretary, “that this man Lyndon is actually here.”

With a graceful gesture Lord Lammersfield indicated where I was standing.

“Let me introduce you to each other,” he said. “Mr. Neil Lyndon — Sir George Frinton.”

I bowed respectfully, and when I raised my head again I saw that the Home Secretary was contemplating me with a puzzled stare.

“You — your face seems strangely familiar to me,” he observed.

“You evidently have a good memory, Sir George,” I replied. “I had the honour and pleasure of travelling up from Exeter to London with you about a fortnight ago.”

A sudden light came into his face, and adjusting his spectacles he stared at me harder than ever.

“God bless my soul!” he exclaimed. “Of course, I remember now.” He paused. “And do you mean to tell me that you — an escaped convict — were actually aware that you were travelling with the Home Secretary?”

I saw no reason for dimming the glory of the incident.

“You were kind enough to give me one of your cards,” I reminded him.

“Why, yes, to be sure; so I did — so I did.” Again he paused and gazed at me with a sort of incredulous amazement. “You must have nerves of steel, sir. Most men in such a situation would have been paralysed with terror.”

The idea of Sir George paralysing anybody with terror struck me as so delightful that I almost burst out laughing, but by a great effort I just managed to restrain myself.

“As an escaped convict,” I said, “one becomes used to rather desperate situations.”

Lammersfield, the corner of whose mouth was twitching suspiciously, broke into the conversation.

“It was a remarkable coincidence,” he said, “but you see how it confirms Casement’s story if any further confirmation were needed.”

Sir George nodded. “Yes, yes,” he said. “I suppose there can be no doubt about it. The proofs of it all seem beyond question.” He turned to me. “Taking everything into consideration, Mr. Lyndon, you appear to have acted in a most creditable and patriotic manner. I understand that the moment you discovered the nature of the plot in which you were involved you placed yourself entirely at the disposal of the Secret Service. That is right, Mr. Latimer, is it not?”

Latimer stepped forward. “If Mr. Lyndon had chosen to do it, sir,” he said, “he could have sold his invention to Germany and escaped with the money. At that time he had no proof to offer that he had been wrongly convicted. Rather than betray his country, however, he was prepared to return to prison and serve out his sentence.”

As an accurate description of my attitude in the matter it certainly left something to be desired, but it seemed to have a highly satisfactory effect upon Sir George. He took a step towards me, and gravely and rather pompously shook me by the hand.

“Sir,” he said, “permit me to congratulate you both on your conduct and on the dramatic establishment of your innocence. It will be my pleasant duty as Home Secretary to see that every possible reparation is made to you for the great injustice that you have suffered.”

Lammersfield, who had gone back to his seat at the table, again interrupted.

“You agree with me, don’t you, Frinton, that, pending any steps you and the Prime Minister choose to take in the matter, Mr. Lyndon may consider himself a free man?”

Sir George seemed a trifle embarrassed. “Well — er — to a certain extent, most decidedly. I have informed Scotland Yard that he has voluntarily surrendered himself to the Secret Service, so there will be no further attempt to carry out the arrest. I — I presume that Mr. Casement and Mr. Latimer will be officially responsible for him?”

The former gave a reassuring nod. “Certainly, Sir George,” he observed.

“I am entirely in your hands, sir,” I put in. “There are one or two little things I wanted to do, but if you prefer that I should consider myself under arrest —”

“No, no, Mr. Lyndon,” he interrupted; “there is no necessity for that — no necessity at all. Strictly speaking, of course, you are still a prisoner, but for the present it will perhaps be best to avoid any formal proceedings. I understand that both Lord Lammersfield and Mr. Casement consider it advisable to keep the whole matter as quiet as possible, at all events until the return of the Prime Minister. After that we must decide what steps it will be best to take.”

“I am very much obliged to you,” I said. “There is one question I should like to ask if I may.”

He took off his spectacles and polished them with his pocket-handkerchief. “Well?” he observed encouragingly.

“I should like to know whether Savaroff’s daughter is in custody — the girl who gave the police their information about me.”

“Ah!” he said, with some satisfaction, “that is a point on which you all appear to have been misled. I have just enlightened Mr. Casement in the matter. The information on which the police acted was not supplied by a girl.” He paused. “It was given them by your cousin and late partner, Mr. George Marwood.”

“What!” I almost shouted; and I heard Tommy indulge in a half-smothered exclamation which was not at all suited to our distinguished company.

Sir George, who was evidently pleased with our surprise, nodded his head.

“Mr. Marwood rang up Scotland Yard at half-past ten last night. He told them he had received an anonymous letter giving two addresses, at one of which you would probably be found. He also gave a full description of the alterations in your appearance.”

I turned to Latimer. “I suppose it was Sonia,” I said. “I never dreamed of her going to him, though.”

“It was very natural,” he replied in that unconcerned drawl of his. “She knew that your cousin would do everything possible to get you under lock and key again, and at the same time she imagined she would avoid the risk of being arrested herself.”

“Quite so, quite so,” said Sir George, nodding his head sagely. “From all I can gather she seems to be a most dangerous young woman. I shall make a particular point of seeing that she is arrested.”

His words came home to me with a sudden swift stab of pity and remorse. It was horrible to think of Sonia in jail — Sonia eating out her wild passionate heart in the hideous slavery I knew so well. The thought of all that she had risked and suffered for my sake crowded back into my mind with overwhelming force. I took a step forward.

“Sir George,” I said, “a moment ago you were good enough to say that the Government would try and make me some return for the injustice I have suffered.”

He looked at me in obvious surprise. “Certainly,” he said — “certainly. I am convinced that they will take the most generous view of the circumstances.”

“There is only one thing I ask,” I said. “Except for this girl, Sonia Savaroff, the Germans would now be in possession of my invention. If the Government feel that they owe me anything, they can cancel the debt altogether by allowing her to go free.”

Sir George raised his eyeglass. “You ask this after she did her best to send you back to penal servitude?”

I nodded. “I am not sure,” I said, “that I didn’t thoroughly deserve it.”

For a moment Sir George stared at me in a puzzled sort of fashion.

“Very well,” he said; “I think it might be arranged. As you say, she was of considerable assistance to us, even if it was unintentionally. That is a point in her favour — a distinct point.”

“How about our friend Mr. Marwood?” put in Lammersfield pleasantly. “Between perjury and selling Government secrets I suppose we have enough evidence to justify his arrest?”

“I think so,” said Sir George, nodding his head solemnly. “Anyhow I have given instructions for it. In a case like this it is best to be on the safe side.”

My heart sank at his words. Charming as it was to think of George in the affectionate clutch of a policeman, I could almost have wept at the idea of being robbed of my own little interview with him, to which I had been looking forward for so long. It was Lammersfield who broke in on my disappointment. “I should imagine,” he said considerately, “that you two, as well as Latimer, must be half starving. I suppose you have had nothing to eat since breakfast.”

Tommy rose to his feet with an alacrity that answered the question so far as he was concerned, and I acknowledged that a brief interval for refreshment would be by no means unwelcome.

“Well, I’m afraid I can’t spare Latimer just yet,” he said, “but you two go off and have a good lunch. Come back here again as soon as you’ve done. I will ring up the War Office and the Admiralty while you are away, and we will arrange for a couple of their men to meet us here, and then you can explain about your new explosive. I fancy you will find them quite an appreciative audience.”

He pressed a bell by his side, and getting up from the table, accompanied us to the door, where I stopped for a moment to try and express my thanks both to him and Sir George.

“My dear Mr. Lyndon,” he interrupted courteously, “you have been in prison for three years for a crime that you didn’t commit, and in return for that you have done England a service that it is almost impossible to overrate. Under the circumstances even a Cabinet Minister may be excused a little common civility.”

As he spoke there came a knock at the door, and in answer to his summons the impassive butler person appeared on the threshold.

“Show these gentlemen out, Simpson,” he said, “and let me know directly they return.” Then, shaking my hand in a friendly fashion, he added with a quizzical smile, “If you should happen to come across any mutual acquaintance of ours, perhaps you will be kind enough to convey my unofficial congratulations. I hope before long to have the privilege of offering them personally.”

I promised to deliver his message, and, following our guide downstairs, we passed out into the street.

“I like that chap,” said Tommy. “He’s got no silly side about him. Joyce always said he was a good sort.”

He stopped on the pavement, and with his usual serene disregard for the respectabilities proceeded to fill and light a huge briar pipe.

“What’s the programme now?” he inquired. “I’m just dying for some grub.”

“We’ll get a taxi and run down to the flat and pick up Joyce,” I said. “Then we’ll come back to the Café Royal and have the best lunch that’s ever been eaten in London.”

Tommy indulged in one of his deep chuckles.

“If anyone’s expecting me in Downing Street before six o’clock,” he observed, “I rather think he’s backed a loser.”

It was not until we were in a taxi, and speeding rapidly past the House of Commons, that I broached the painful subject of George.

“I don’t know what to do,” I said. “If he’s at his house, he has been arrested by now, and if he isn’t the police will probably find him before I shall. It will break my heart if I don’t get hold of him for five minutes.”

Tommy grunted sympathetically. “It’s just on the cards,” he said, “that Joyce might know where he is.”

Faint as the chance seemed, it was sufficient to cheer me up a little, and for the rest of the drive we discussed the important question of what we should have for lunch. After a week of sardines and tinned tongue I found it a most inspiring topic.

As we reached the Chelsea Embankment a happy idea presented itself to me. “I tell you what, Tommy,” I said. “We won’t go and knock at Joyce’s flat. Let’s slip round at the back, as we did before, and take her by surprise.”

“Right you are,” he said. “She’s probably left the studio door open. She generally does on a hot afternoon like this.”

The taxi drew up at Florence Court, and telling the driver to wait for us, we Walked down the passage and turned into Tommy’s flat. There were several letters for him lying on the floor inside, and while he stopped to pick them up, I passed on through the studio and out into the little glass-covered corridor at the back.

It was quite a short way along to Joyce’s studio, and from where I was I could see that her door was slightly ajar. I stepped quietly, so as not to make any noise, and I had covered perhaps half the distance, when suddenly I pulled up in my tracks as if I had been turned into stone. For a moment I stood there without moving or even breathing. A couple of yards away on the other side of the door I could hear two people talking. One of them was Joyce; the other — the other — well, if I had been lying half-unconscious on my death-bed I think I should have recognized that voice!

There was a sound behind me, and whipping noiselessly round I was just in time to signal to Tommy that he must keep absolutely quiet. Then with my heart beating like a drum I crept stealthily forward until I was within a few inches of the open door. I was shaking all over with a delight that I could hardly control.

“…you quite understand.” (I could hear every word George was saying as plainly as if I were in the room.) “I only have to ring up the police, and in half an hour he’ll be back again in prison — back for the rest of his life. He won’t escape a second time — you can be sure of that.”

“Well?”

The single word came clear and distinct, but it would be difficult to describe the scorn which Joyce managed to pack into it. It had some effect on George.

“You have just got to do what I want — that’s all,” he exclaimed angrily. “I leave England tonight, and unless you come with me I shall go straight from here and ring up Scotland Yard. You can make your choice now. You either come down to Southampton with me this evening, or Lyndon goes back to Dartmoor tomorrow.”

“Then you were lying when you said you were anxious to help him?”

With a mighty effort George apparently regained some control over his tongue.

“No, I wasn’t, Joyce,” he said. “God knows I’m sorry for the poor devil — I always have been; but there’s nothing in the world that matters to me now except you. I — I lost my temper when you said you wouldn’t come. You didn’t mean it, did you? Lyndon can never be anything to you; he is dead to all of us. At the best he can only be a skulking convict hiding from the police in South America or somewhere. You come with me; you shall never be sorry for it. I’ve plenty of money, Joyce; and I’ll give you the best time a woman ever had.”

“And if I refuse?” asked Joyce quietly.

It was evident from the sound that George had taken a step towards her.

“Then Lyndon will go back to Dartmoor and stop there till he rots and dies.”

There was a short pause, and then very clearly and deliberately Joyce gave her answer.

“I think you are the foulest man in the world,” she said. “It makes me sick to be in the same room with you.”

The gasp of fury and astonishment that broke from George’s lips fell on my ears like music. He was so choking with rage that for a moment he could hardly speak.

“Damn you!” he stuttered at last. “So that’s your real opinion, is it! That’s what you’ve been thinking all along! Trying to use me to help that precious convict lover of yours — eh?”

I heard him come another step nearer.

“I’ll make you pay for this, anyhow,” he snarled. “Sick at being in the same room with me, are you? Then by God I’ll give you some reason —”

With a swift jerk I flung open the door and stepped in over the threshold.

“Not this time, George dear,” I said.

If the devil himself had shot up through the floor in a crackle of blue flame, I don’t think it could have had a more striking effect on my late partner. With his mouth open and his face the colour of freshly mixed putty, he stood perfectly still in the centre of the room, gazing at me like a man in a trance. For a second — a whole beautiful rich second — he remained in this engaging attitude; then, as if struck by an electric shock, he suddenly spun round with the obvious intention of making a dart for the door.

The idea was distinctly a sound one, but it was too late to be of any practical value. Directly he moved I stepped in, and catching him a smashing box on the ear with my right hand sent him sprawling full length on the carpet. Joyce laughed gaily, while lounging across the room Tommy set his back against the door and beamed cheerfully on the three of us.

“Quite a little family party,” he observed.

Joyce was in my arms, and we were kissing each other in the most shameless and unabashed way.

“Oh, my dear,” she said, “I hope you haven’t hurt your hand.”

“It stung a bit,” I admitted, “but I’ve got another one — and two feet.” I put her gently aside. “Get up, George,” I said.

He lay where he was, pretending to be unconscious.

“If you don’t get up at once, George,” I said softly, “I shall kick you — hard.”

He scrambled to his feet, and then crouched back against the wall eyeing me like a trapped weasel.

I indulged myself in a good heart-filling look at him.

“So you’ve been sorry for me, George?” I said. “All these three long weary years that I’ve been rotting in Dartmoor, you’ve been really and truly sorry for me?”

He licked his lips and nodded.

I laughed. “Well, I’m sorry for you now, George,” I said — “damned sorry.”

If anything, the putty-like pallor of his face became still more ghastly.

“Don’t do anything violent, Neil,” he whispered. “You’ll only regret it. I swear to you —”

“I shouldn’t swear,” I said. “You don’t want to die with a lie on your lips.”

The sweat broke out on his forehead, and he glanced desperately round the room, as though seeking for some possible method of escape. The only comfort he got was a shake of the head from Tommy.

“You — you don’t mean to murder me?” he gasped.

I gave a fiendish laugh. “Don’t I!” I cried. “What’s one murder more or less? I know you’ve put the police on to me, and I’d sooner be hanged than go back to Dartmoor any day.”

Tommy rubbed his hands together ghoulishly. “What are we going to do with him?” he asked. “Cut his throat?”

“No,” I said. “It would make a mess, and we don’t want to spoil Joyce’s carpet.”

“Oh, it doesn’t matter about the carpet,” said Joyce unselfishly.

“I’ve got it,” said Tommy. “Why not throw him in the river? The tide’s up; I noticed it as we came along.”

Whether he intended the suggestion seriously or not I don’t know, but I rose to it like a trout to a fly. There are seldom more than two feet of water at high tide at that particular part of the Embankment, and the thought of dropping George into its turbid embrace filled me with the utmost enthusiasm.

“By Jove, Tommy!” I exclaimed. “That’s a brilliant idea. The Thames water’s about the only thing he wouldn’t defile.”

I stepped forward, and before George knew what was happening I had swung him round and clutched him by the collar and breeches.

“Open the door,” I said, “and just see there’s no one in the passage.”

With a deep chuckle Tommy turned to obey, while Joyce laughed with a viciousness that I should never have given her credit for. As for Georg e— well, I suppose in his blind terror he really thought he was going to be drowned, for he kicked and struggled and raved till it was as much as I could do to hold him.

“All clear!” sang out Tommy from the hall.

“Stand by, then,” I said, and taking a deep breath, I ran George through the flat down the passage, and out into the street, in a style that would have done credit to the chucker out at the Empire.

There were not many people about, and those that were there had no time to interfere even if they had wanted to do so. I just got a glimpse of the startled face of our taxi driver as he jumped aside to let us pass, and the next moment we had crossed the road and fetched up with a bang against the low Embankment wall.

I paused for a moment, renewed my grip on George’s collar, and took a quick look round. Tommy was beside me, and a few yards away, down at the bottom of some steps, I saw a number of small boys paddling in the water. There was evidently no risk of anybody being drowned.

“I’ll take his feet,” said Tommy, suiting the action to the word. “You get hold of his arms.”

There was a brief struggle, a loud scream for help, and the next moment George was swinging merrily between us.

“One! Two! Three!” I cried.

At the word “three” we let go simultaneously. He flew up into the air like a great wriggling crab, twisted round twice, and then went down into the muddy water with a splash that echoed all over the Embankment.

“Very nice,” said Tommy critically. “But we ought to have put a stone round his neck.”

One glance over the wall showed me that there was no danger. Dripping, floundering, and gasping for breath, George emerged from the surface like a frock-coated Neptune rising from the waves. He seemed to be trying to speak, but the shrieks of innocent delight with which his reappearance was greeted by the paddling boys unfortunately prevented us from hearing him.

I thrust my arm through Tommy’s. “Come along,” I said. “We must get out of this before there’s a row.”

Swift as we had been about it, our little operation had already attracted a certain amount of notice. People were hurrying up from all directions, but without paying any attention to them, we walked back towards the taxi, the driver of which had apparently been too astonished to move.

“Gor blimey, Guv’nor,” he ejaculated, “what sorter gime d’you call that?”

“It’s all right, driver,” said Tommy gravely. “We found him insulting this gentleman’s sister.”

The driver, who evidently had a nice sense of chivalry, at once came round to our side.

“Was ‘e? — the dirty ‘ound!” he observed. “Well, you done it on ‘im proper. You ain’t drowned ‘im, ‘ave ye, gents?”

“Oh no,” I said. “He’s addressing a few words to the crowd now.” Then seeing Joyce standing in the doorway I hurried up the steps.

“Joyce dear,” I said, “put on a hat and come as quick as you can. It’s quite all right, but we want to get out of this before there’s any bother.”

She nodded, and disappeared into the flat, while I strolled back to the taxi.

It was evident from a movement among the spectators that George was making his way towards the steps. Some of them who had come running up kept turning round and casting curious glances at us, but so far no one had attempted to interfere. It was not until Joyce was just coming out of the flats, that a man detached himself from the crowd and started across the road. He was a big, fat, greasy person in a bowler hat.

“Here,” he said. “You wait a bit. What d’ye mean by throwing that pore man in the river?”

I opened the door of the taxi and Joyce jumped in.

“What’s it got to do with you, darling?” asked Tommy affably.

“What’s it got to do with me!” he repeated indignantly. “Why, it’s just the mercy o’ Gawd —”

“Come on, Tommy,” I said.

Tommy took a step forward, but the man clutched him by the arm.

“No yer don’t,” he said, “not till… Ow!”

With a sudden vigorous shove Tommy sent him staggering back across the pavement, and the next moment we had both jumped into the taxi and banged the door.

“Right away,” I called out.

I think there was some momentary doubt amongst the other spectators whether they oughtn’t to interfere, but before they could make up their minds our sympathetic driver had thrust in his clutch, and we were spinning away down the Embankment.

Joyce, who was sitting next to me, slipped her hand into mine.

“I love to see you both laughing,” she said, “but I should like to know what’s happened! At present I feel as if I was acting in a cinematograph play.”

We told her—told her in quick, eager sentences of how the danger and mystery that had hung over us so for long had at last been scattered and destroyed. It was a broken, inadequate sort of narrative, jerked out as we bumped over crossings and pulled by behind buses, but I fancy from the light in her eyes and the pressure of her hand that Joyce was quite contented.

“It’s — it’s like waking up after some horrible dream,” she said, “and suddenly finding that everything’s all right. Oh, I knew it would be in the end — I knew it the whole time — but I never dreamed it would happen all at once like this.”

“Neither did George,” chuckled Tommy. “How long had he been with you, Joyce?”

“About twenty minutes,” she said. “He came straight to me from Harrod’s, where he’s spent most of the day buying stores for his yacht. He had quite made up his mind I was coming with him. I don’t believe he’s got the faintest idea about what’s happened this morning.”

“He will have soon,” I said. “That’s why I threw him in the river. He’s bound to go back to the house for a change of clothes, and he’ll find the police waiting for him there.”

“That’ll be just right,” observed Tommy complacently. “There’s nothing so good as a little excitement to stop one from catching cold.”

“Except lunch,” I added, as the taxi rounded the corner of Piccadilly and drew up outside the Café Royal.

What the manager of that renowned restaurant must have thought of us, I find it rather difficult to guess. It is not often, I should imagine, that two untidy mud-stained men and a beautiful girl turn up at four o’clock in the afternoon and demand the best meal that London can provide.

Fortunately, however, he proved to be a gentleman of philosophy and resource. He accepted our request with perfect composure, and by the time we had succeeded in making ourselves passably respectable he presented us with a menu that deserved to be set to music.

Heavens, what a lunch that was! We ate it all by ourselves in the big empty restaurant, with half a dozen fascinated waiters eyeing us from the end of the room. They were probably speculating as to whether we were eccentric millionaires, or whether we had just escaped from some private lunatic asylum, but we were all far too cheerful to care what they thought. We ate, we drank, we laughed, we talked, with a reckless jubilant happiness that would have survived the scrutiny of all the waiters in London.

“I know what we’ll do, Joyce,” I said, when at last the dessert was cleared away and we were sitting in a delicate haze of cigar smoke. “As soon as things are fixed up I’ll buy a good second-hand thirty-ton boat, and you and I and Tommy will go off for a six months’ cruise. We’ll take Mr. Gow as skipper, and your little page-boy as steward, and we’ll run down to the Mediterranean and stop there till people are tired of gassing about us.”

“That will be beautiful,” said Joyce simply.

“I’ll come,” exclaimed Tommy, “unless the Secret Service refuse to give me up.” Then he stopped and looked mischievously across at Joyce and me. “It’s a pity we can’t ask Sonia too,” he added.

“Poor Sonia,” said Joyce. “I am so glad you got her off.”

“Are you really?” asked Tommy. “That shows I know nothing about women. I always thought that if two girls loved the same man they hated each other like poison.”

Joyce nodded. “So they do as a rule.”

“Well, Sonia loved Neil all right; you can take my word for it.”

Joyce laughed softly. “Yes, Tommy dear,” she said, “but then, you see, Neil didn’t love her — and that just makes all the difference.”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”