A Rogue By Compulsion (24)

By:

September 4, 2016

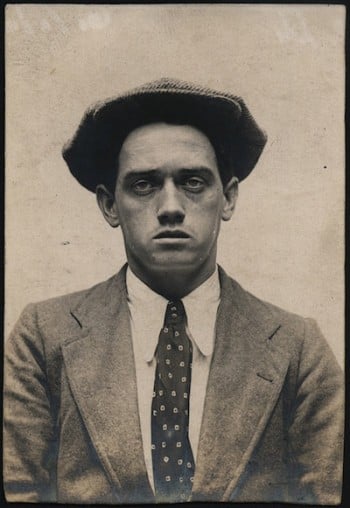

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

It was Tommy who pronounced his epitaph. “Well,” he observed, “he was a damned scoundrel, but he played a big game anyhow.”

Latimer thrust his hand into the dead man’s pocket, and drew out a small nickel-plated revolver. One chamber of it was discharged.

“Not a bad shot,” he remarked critically. “Fired at me through his coat, and only missed my head by an inch.”

He got up and looked round the room at the shattered window and the other traces of the fray, his gaze coming finally to rest on the prostrate figure of Savaroff.

“That was a fine punch of yours, Lyndon,” he added. “I hope you haven’t broken his neck.”

“I don’t think so,” I said. “Necks like Savaroff’s take a lot of breaking.” Then, suddenly remembering, I added hastily: “By the way, you know that there are two more of the crowd — Hoffman and a friend of von Brünig’s? They might be back any minute.”

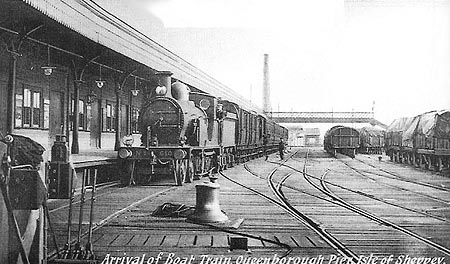

Latimer shook his head almost pensively. “It’s improbable,” he said. “I have every reason to believe that at the present moment they are in Queenborough police station.”

I saw Tommy grin, but before I could make any inquiries von Brünig had scrambled to his feet. His face looked absolutely ghastly in its mingled rage and disappointment. After a fashion I could scarcely help feeling sorry for him.

“I demand an explanation,” he exclaimed hoarsely. “By what right am I arrested?”

Latimer walked up to him, and looked him quietly in the eyes.

“I think you understand very well, Captain von Brünig,” he said.

There was a pause, and then, with a glance that embraced the four of us, the German walked to the couch and sat down. If looks could kill I think we should all have dropped dead in our tracks.

Providence, however, having fortunately arranged otherwise, we remained as we were, and at that moment there came from outside the unmistakable sound of an approaching car. I saw Latimer open his watch.

“Quick work, Ellis,” he remarked, with some satisfaction. “I wasn’t expecting them for another ten minutes. Tell them to come straight in.” He snapped the case and turned back to me. “Suppose we try and awake our sleeping friend,” he added. “He looks rather a heavy weight for lifting about.”

Between us we managed to hoist Savaroff up into a chair, while Tommy stepped across the room and fetched a bottle of water which was standing on the sideboard. I have had some practice in my boxing days of dealing with knocked-out men, and although Savaroff was a pretty hard case, a little vigorous massage and one or two good sousings soon produced signs of returning consciousness. Indeed, he had just recovered sufficiently to indulge in a really remarkable oath when the door swung open and Ellis came back into the room, accompanied by two other men. One of them was dressed in ordinary clothes, the other wore the uniform of a police sergeant.

I shall never forget the face of the latter as he surveyed the scene before him.

“Gawd bless us!” he exclaimed. “What’s up now, sir? Murder?”

“Not exactly, Sergeant,” replied Latimer soothingly. “I shot this man in self-defence. The other two I give into your charge. There is a warrant out for all three of them.”

It appeared that the sergeant knew who Latimer was, for he treated him with marked deference.

“Very well, sir,” he said. “If ‘e’s dead, ‘e’s dead; anyhow, I’ve orders to take my instructions entirely from you.” Then, dragging a note-book out of his pocket, he added with some excitement: “There’s another thing, sir, a matter that the Tilbury station have just telephoned through about. It seems” — he consulted his references — “it seems that when they were in that launch of theirs they run down a party o’ coast-guards, who’d got hold of Lyndon, the missing convict. Off Tilbury it was. D’you happen to know anything about this, sir?”

Latimer nodded his head. “A certain amount, Sergeant,” he said. “You will find the launch in the creek at the bottom of the cliff.” He paused. “This is Mr. Neil Lyndon,” he added; “I will be responsible for his safe keeping.”

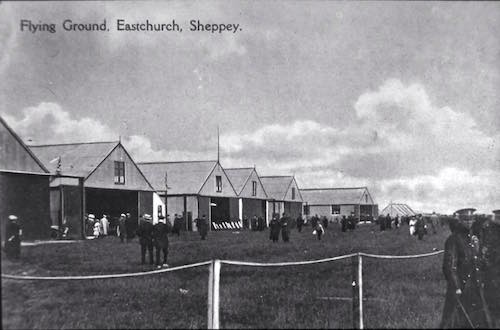

I don’t know what sort of experiences the Isle of Sheppey usually provides for its police staff, but it was obvious that, professionally speaking, the sergeant was having the day of his life. He stared at me for a moment with the utmost interest, and then, recollecting himself, turned and saluted Latimer.

“Very good, sir,” he said; “and what do you want me to do?”

“I want you to stay here for the present with one of my men, while we go to the station. I shall send the car back, and then you will take the two prisoners into Queenborough. My man will remain in charge of the bungalow.”

The sergeant saluted again, and Latimer turned to me.

“You and Morrison must come straight to town,” he said. “We shall just have time to catch the twelve-three.”

It was at this point that Savaroff, who had been regarding us with the half-stupid stare of a man who has newly recovered consciousness, staggered up unsteadily from his chair. His half-numbed brain seemed suddenly to have grasped what was happening.

“Verfluchter Schweinhund!” he shouted, turning on me. “So it was you, then —”

He got no further. However embarrassed the sergeant might be by exceptional events, he was evidently thoroughly at home in his own department.

“’Ere!” he said, stepping forward briskly, “stow that, me man!” And with a sudden energetic thrust in the chest, he sent Savaroff sprawling backwards on the couch almost on top of von Brünig.

“Don’t you use none of that language ’ere,” he added, standing over them, “or as like as not you’ll be sorry for it.”

There was a brief pause. “I see, Sergeant,” said Latimer gravely, “that I am leaving the case in excellent hands.”

He gave a few final instructions to Ellis, who was also staying behind, and then the four of us left the bungalow and walked quietly down the small garden path that led to the road. Just outside the gate stood a powerful five-seated car.

“Start her up, Guthrie,” said Latimer; and then turning to us, he added, with a smile: “I want you in front with me, Lyndon. I know Morrison’s dying for a yarn with you, but he must wait.”

Tommy nodded contentedly. “I can wait,” he observed; “it’s a habit I’ve cultivated where Neil’s concerned.”

We all clambered into the car, and, slipping in his clutch Latimer set off at a rapid pace in the direction of Queenborough. It was not until we had rounded the first corner that he opened the conversation.

“How did you know about Marks?” he asked, in that easy drawling voice of his.

“I didn’t know for certain,” I said quietly. “It was more or less of a lucky shot.”

Then, as he seemed to be waiting for a further explanation, I repeated to him as briefly as possible what Sonia had told me about McMurtrie’s reason for visiting London.

“I didn’t go into all this in my letter to you,” I finished, “because in the first place there was only just time for Joyce to catch the train, and in the second I didn’t want to disappoint her in case it should turn out to be all bunkum. You must have been rather amazed when I suddenly sprung it on McMurtrie.”

He shook his head, smiling. “Oh no,” he said — “hardly amazed.” He paused. “You see, I knew about it already,” he added placidly.

If there was any amazement to spare at that moment it was certainly mine.

“You knew about it!” I repeated. “You knew that McMurtrie had killed Marks?”

He nodded coolly. “You remember telling me in the boat that your friend Miss — Miss Aylmer, isn’t it? — had recognized him as the man she saw at the flat on the day of the murder?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, if that was so, and you had been wrongly convicted, which I was inclined to believe, the doctor’s presence on the scene seemed to require a little looking into. I knew that at that time he had only just arrived in London, so the odds were that he and Marks were old acquaintances. I hunted up the evidence in your trial — I had rather forgotten it — and I found just what I expected. Beyond the fact that Marks was a foreigner and had been living in London for about eight years, no one seemed to know anything about him at all. The police were so confident in their case against you that apparently they hadn’t even bothered to make the usual inquiries. If they had taken the trouble to communicate with St. Petersburg, they could have found out all about Mr. Marks without much difficulty. The authorities there have a wonderfully complete system of remembering their old friends.”

“But three years afterwards —” I began.

“It makes very little difference, especially as just at present we are on excellent terms with the Russian Secret Service. They took the matter up for me, and last night I got the full particulars I wanted about the man who had given away McMurtrie and his friends in St. Petersburg. There can be no question that he and Marks were the same person.”

I took a long — a very long breath.

“There remains,” I said, “the Home Office.”

“I don’t think you need be seriously worried about the Home Office,” returned Latimer serenely. “By this time they have a full statement of the case — except, of course, for my direct evidence that I heard the doctor actually bragging of his achievement. I had a long interview with Casement before I left London this morning, and he said he would go round directly after breakfast. He evidently arrived just too late to prevent the order for your arrest.”

I nodded. “Sonia must have gone to the police last night,” I said; and then in a few words I told him of the telegram I had received from Gertie ‘Uggins, and how it had just enabled me to get away.

“I don’t know,” I finished, “how much my double escape complicates matters. However unjust my sentence was, there’s no denying I’ve committed at least three felonies since. I’ve broken prison, plugged a warder in the jaw, and shoved an oar into a policeman’s tummy. Do you think there’s any possible chance of the Home Secretary being able to overlook such enormities?”

Latimer laughed easily. “My dear Lyndon,” he said, “in return for what you’ve done for us, you could decimate the police force if you wanted to.” Then, speaking more seriously, he added: “I tell you frankly, there’s every chance of a huge European war in the near future, and you can see the different position we should be in if the Germans had got hold of this new powder of yours. Apart from that, the Government owe you every possible sort of reparation for the shameful way you’ve been treated. If there’s any ‘overlooking’ to be done, it will be on your side, not on theirs.”

We were entering the dreary main street of Queenborough as he spoke, and before I could answer he drew up outside the post-office.

“We’ve just time to send off a telegram,” he said. “I want to make sure of seeing Lammersfield and Casement directly we get to town. They will probably be at lunch if I don’t wire.”

He entered the building, and Tommy took advantage of his brief absence to lean over the back of the seat and grip my hand.

“We’ve done it, Neil,” he said. “Damn it, we’ve done it!”

“You’ve done it, Tommy,” I retorted. “You and Joyce between you.”

There was a short pause, and then Tommy gave vent to a deep satisfied chuckle.

“I’m thinking of George,” he said simply.

It was such a beautiful thought that for a moment I too maintained a voluptuous silence.

“We must find out whether they’re going to prosecute him,” I said. “I don’t want to clash with the Government, but whatever happens I mean to have my five minutes first. They’re welcome to what’s left of him.”

Tommy nodded sympathetically, and just at that moment Latimer came out of the post-office.

We got to the railway station with about half a minute to spare. The train was fairly crowded, but a word from Latimer to the station-master resulted in our being ushered into an empty “first” which was ceremoniously locked behind us. It was not a “smoker,” but with a fine disregard for such trifles Latimer promptly produced his cigar case, and offered us each a delightful-looking Upman. There are certainly some advantages in being on the side of the established order.

Soothed by the fragrant tobacco, and with an exquisite feeling of rest and freedom, I lay back in the corner and listened to Latimer’s pleasantly drawling voice, as he described to me how he had accomplished his morning’s coup.

It seems that, accompanied by Tommy and his own man Ellis, he had arrived at Queenborough by the early train. Instructions had already been wired through from London that the Sheppey police were to put themselves entirely at his disposal; and having commandeered a car, the three of them, together with our friend the sergeant, set off to the bungalow. They pulled up some little distance away and waited for Guthrie, Latimer’s other assistant, who had been keeping an eye on the place during the night. He reported that McMurtrie and Savaroff and von Brünig had just put off in the launch, leaving the other two behind.

“I guessed they had gone to pay you a visit,” explained Latimer drily, “and it seemed to me a favourable chance of doing a little calling on our own account.”

The net result of that little call had been the bloodless capture of Hoffman and the other German spy, who had been surprised in the prosaic act of swallowing their breakfast.

Having been favoured by fortune so far, Latimer had promptly proceeded to make the best use of his opportunity. It struck him that, whatever might be the result of their visit to me, the other members of the party were pretty sure to come back to the bungalow. The idea of hiding behind the curtain at once suggested itself to him. It was just possible that in this way he might pick up some valuable information before he was discovered, while in any case it would give him the advantage of taking them utterly by surprise.

His first step had been to tie up the prisoners, and pack them off in the car to Queenborough police station with Guthrie and the sergeant as an escort. (I should have loved to have heard his conversation with Hoffman while the former operation was in progress!) He then carefully removed all inside and outside traces of the raid on the bungalow, and picked out a couple of convenient hiding-places in the garden, where Tommy and Ellis could he in ambush until they were wanted. A shot from his revolver or the smashing of the French window was to be the signal for their united entrance on the scene.

“Well, you know the end of the story as well as I do,” he finished, nicking off the ash of his cigar. “Things could scarcely have turned out better, except for that unfortunate accident with McMurtrie.” He paused. “I wouldn’t have shot him for the world,” he added regretfully, “but he really left me no choice.”

“He would have been hanged anyway,” put in Tommy consolingly.

Latimer smiled. “I didn’t mean to suggest that it was likely to keep me awake at night. I was only thinking that we might perhaps have got some useful information out of him.”

“It seems to me,” I said gratefully, “that we did.”

Through the interminable suburbs and slums of South-East London we steamed slowly into London Bridge Station and drew up at the platform. There was a taxi waiting almost opposite our carriage, and promptly securing the driver Latimer instructed him to take us “as quickly as possible” to No. 10 Downing Street.

The man carried out his order with almost alarming literalness, but Providence watched over us and we reached the Foreign Office without disaster. Favoured with a respectful salute from the liveried porter on duty, Latimer led the way into the hall.

We followed him down a short narrow passage to another corridor, where he unlocked and opened a door on the left, ushering us into a small room comfortably fitted up as an office.

“This is my own private den,” he said; “so no one will disturb you. I will go and see if Casement has come. If so, he is probably upstairs with Lammersfield. I will give them my report, and then no doubt they will want to see you. You won’t have to wait very long.”

He nodded pleasantly and left the room, closing the door after him. For all his quiet, almost lethargic manner, it was curious what an atmosphere of swiftness and decision he seemed to carry about with him.

I turned to Tommy.

“Where’s Joyce?” I asked.

“She’s at the flat,” he announced. “She said she would wait there until she heard from us. I saw her last night, you know. I was having supper at Hatchett’s with Latimer when she turned up with your letter. She’d come on from his rooms.”

“There are many women,” I said softly, “but there is only one Joyce.”

Tommy chuckled. “That’s what Latimer thinks. After she left us—I was staying the night with him in Jermyn Street and we’d all three gone back there to talk it over—he said to me in that funny drawling way of his: ‘You know, Morrison, that girl will be wasted, even on Lyndon. She ought to be in the Secret Service.'”

I laughed. “I’m grateful to the Secret Service,” I said, “but there are limits even to gratitude.”

For perhaps three-quarters of an hour we remained undisturbed, while Latimer was presumably presenting his report to the authorities. Every now and then we heard footsteps pass down the corridor, and on one occasion an electric bell went off with a sudden vicious energy that I should never have expected in a Government office. The time passed quickly, for we had plenty to talk about; indeed, our only objection to waiting was the fact that we were both beginning to get infernally hungry, and it seemed likely to be some time yet before we should be able to get anything to eat.

At last there came a discreet knock at the door, and an elderly clean-shaven person with the manners of a retired butler appeared noiselessly upon the threshold. He bowed slightly to us both.

“Lord Lammersfield wishes to see you, gentlemen. If you will be good enough to follow me, I will conduct you to his presence.”

We followed him along the corridor and up a rather dingy staircase, when he tapped gently at a door immediately facing us. “Come in,” called out a voice, and with another slight inclination of his head our guide turned the handle and ushered us into the room.

It was a solemn-looking sort of apartment furnished chiefly with bookcases, and having a general atmosphere of early Victorian stuffiness. At a big table in the centre two men were sitting. One was Latimer; the other I recognized immediately as Lord Lammersfield.

I had never known him personally in the old days, but I had often seen him walking in the Park, or run across him at such popular rest cures as Kempton and Sandown Park. He had changed very little in the interval; his hair was perhaps a trifle greyer, otherwise he looked just the same debonair picturesque figure that the Opposition caricaturists had loved to flesh their pencils on.

He got up as we entered, regarding us both with a pleasant whimsical smile that put me entirely at my ease at once.

“This is Lyndon,” said Latimer, indicating me; “and this is Morrison.”

Lord Lammersfield came round the table and shook hands cordially with us both.

“Sit down, gentlemen,” he said, “sit down. If half of what Mr. Latimer has told me is true, you must be extremely tired.”

We all three laughed, and Tommy promptly took advantage of the invitation to seat himself luxuriously in a big leather arm-chair. I remained standing.

“To be quite truthful,” I said, “it’s been the most refreshing morning I can ever remember.”

Lord Lammersfield looked at me for a moment with the same smile on his lips.

“Yes,” he said drily; “I suppose there is a certain stimulus in saving England before breakfast. Most of my own work in that line is accomplished in the afternoon.” Then, with a sudden slight change in his manner, he took a step forward and again held out his hand.

“Mr. Lyndon,” he said, “as a member of the Government, and one who is therefore more or less responsible for the law’s asinine blunders, I am absolutely ashamed to look you in the face. I wonder if you add generosity to your other unusual gifts.”

For the second time we exchanged grips. “I have common gratitude at all events, Lord Lammersfield,” I said. “I know that you have tried to help me while I was in prison, and—”

He held up his other hand with a gesture of half-ironical protest. “Ah!” he exclaimed, “I am afraid that any poor efforts of mine in that direction were due to the most flagrant compulsion.” He paused. “Whatever else you are unlucky in, Mr. Lyndon,” he added smilingly, “you can at least be congratulated on your friends.”

Then he turned to Latimer. “I think it would be as well if I explained the position before Casement and Frinton arrive.”

Latimer expressed his agreement, and motioning me to a chair, Lord Lammersfield again seated himself at the table. His manner, though still quite friendly and unstilted, had suddenly become serious.

“For the moment, Mr. Lyndon,” he said, “the Prime Minister is out of London. We have communicated with him, and we expect him back tonight. In his absence it falls to me to thank you most unreservedly both on behalf of the Government and the nation for what you have done. It would be difficult to overrate its importance.”

I began to feel a trifle embarrassed.

“I really don’t want any thanks,” I said. “I just drifted into it; and anyway one doesn’t sell one’s country, even if one is an escaped convict.”

Lord Lammersfield laughed drily. “There are many men,” he said, “in your position who would have found it an extraordinarily attractive prospect. I am not at all sure I shouldn’t have myself.” He paused. “We can’t give you those three years of your life back,” he went on, “but fortunately we can make some sort of amends in other ways. I have no doubt that the moment the Prime Minister is fully acquainted with the circumstances he will arrange for what we humorously call a ‘free pardon’; that is to say, the Law will very graciously forgive you for having been unjustly sent to prison. As for the rest —” he shrugged his shoulders — “well, I don’t imagine you will be precisely the loser for not having sold your secret to the Wilhelmstrasse. Our own War Office are quite prepared to deal in any original methods of scattering death that happen to be on the market just at present.”

There was a brief pause.

“And are we free now?” inquired Tommy, with a rather pathetic glance at the clock.

“You should be very shortly,” returned Lammersfield. “Mr. Casement has gone across to the Home Office to explain the latest developments to Sir George Frinton. We are expecting them both here at any moment.”

“Sir George Frinton?” I echoed. “Why, I thought Mr. McCurdy was at the Home Office.”

Lammersfield smiled tolerantly: “You have been busy, Mr. Lyndon, and some of the more important facts of modern history have possibly escaped you. McCurdy resigned from the Government nearly three months ago.”

“But Sir George Frinton!” I exclaimed. “Why, I know the old boy; I have a standing invitation to go and look him up.” And then, without waiting for any questions, I described to them in a few words how the Home Secretary and I had travelled together from Exeter to London, and the favourable impression I had apparently made.

Both Lammersfield and Latimer were vastly amused—the former lying back in his chair and laughing softly to himself in undisguised merriment.

“How perfectly delightful!” he observed. “Poor old Frinton has his merits, but —”

The libel he was about to utter on his distinguished colleague was suddenly cut short by a knock at the door; and, in answer to his summons, the butler-looking person entered and announced that Sir George Frinton and Mr. Casement were waiting for an audience.

“Show them up at once,” said his lordship gravely; and then turning to Latimer as the man left the room he added, with a reflective smile:

“I should never have believed that the Foreign Office could be so

entertaining.”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”