Animal Magnetism (5)

By:

August 30, 2016

HiLobrow friend and contributor Colin Dickey is author of Cranioklepty & Afterlives of the Saints, as well as a forthcoming book on haunted houses, Ghostland. HILOBROW is pleased to present a brief series of Colin’s previously published essays regarding animals.

In Near Wilds, Part Two

This essay first appeared in Telling Reads.

1.

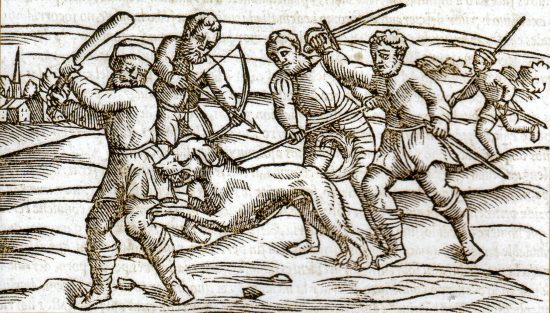

There are many viruses that come from animals, of course (the term is zoonosis), but until the discovery of microbes we were largely ignorant of these transmission routes, even in cases of large epidemics like the plague. Not so with rabies. Rabies, Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy argue in their recent Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus, has a much different cultural history because we’ve always known it to be transmitted from animals — it’s been the one clear example of zoonosis apparent for millennia. As such, Wasik and Murphy contend, “the rabid bite is the visible symbol of the animal infecting the human, of an illness in a creature metamorphosing demonstrably into that same illness in a person.”

Rabies — what the great medieval Arabic physician Ibn Sina called that “serious and venomous melancholy” — is a symbolic crossing of the threshold between human and animal, that terrifying moment when a human descends into the realm of the beasts — and when the rest of us, watching it happen, are confronted with the terrifying reality that the line between the two realms is hopelessly thin. This is why rabies has long been associated with vampires and werewolves. “As the lone visible instance of animal-to-human infection,” Wasik and Murphy write, “rabies has always shaded into something more supernatural: into bestial metamorphoses, into monstrous hybridities.” If the dog straddles two worlds, the human-built and the wild, the rabies virus, by contrast — the small bullet-shaped virus that worms its way into the nervous system, moving towards the brain at a few millimeters a day — offers the threat of a one-way trip, a descent into wildness, followed quickly by death.

2.

In case you’re curious, here’s the moral calculation, in order of the respective values placed on various lives: In the event of a raccoon attack, if the raccoon is still extant, the animal is put to sleep and its brain is autopsied for signs of rabies. You cannot identify rabies while the animal is alive; it must be killed. If no signs of rabies are found in the raccoon, all treatment of the dog and human can immediately cease. If the raccoon is not available — if the animal wasn’t caught and can’t be located — attention then turns to the dog. If the dog has not been vaccinated against rabies, the dog is put to sleep and its brain is autopsied. This is largely a preventative measure; it is done well before any signs of disease manifest, in order to prevent further contamination. It goes without saying that in cases of suspected rabies, the human is never prophylactically put to sleep. Vaccination is the first and only course of action.

In practical terms, what this meant is that until we could prove Alistair’s vaccination history to Animal Control, there was a very real chance he would be put down. In practical terms, what this meant was that I was soon more worried about my dog than my wife, since I was fairly confident she was not going to be put to sleep just to be on the safe side, and because we soon found out that Alistair’s rabies vaccinations were not entirely up to date. In practical terms what this meant was I was soon overwhelmed by guilt because of this. This is what the moral calculation of public health laws can mean: what for one creature, the person, is a few terrifying moments and severe pain, followed by a major inconvenience and a huge deductible at the emergency room is, for another creature, a casual matter of life and death.

In our cultural history, putting down the possibly rabid dog is an old cliché — you find it in To Kill a Mockingbird and in Old Yeller, where, particularly in the latter, it’s the sign of maturity, of becoming a man, of putting aside childish ways and accepting the responsibility that comes with adulthood. (In the film version of Old Yeller, the boy Travis shoots the dog only after it’s clear he’s infected with rabies; in the book, the dog is shot shortly after being bitten by a rabid wolf, before it’s totally clear that the dog has been infected.) To be a man means seeing past emotional attachment, it means doing what’s right even when it’s painful. To be a man means to kill the dog.

In reality, this narrative is as ludicrous as it is offensive. Even as I was working feverishly to figure out what we needed to do to keep our dog out of Animal Control’s hands, scenes of Old Yeller absurdly ran through my head. Killing Alistair would not make a man of me — the idea struck both Nicole and I with equal horror. There is nothing gendered in needless suffering. Nor would putting down the dog prove that Nicole or I was some kind of adult capable of facing the awful truths of the world — particularly when it wouldn’t even be clear that he had the disease. The killing of a pet has no real moral or teleological value; it’s not a life lesson. It speaks to senseless waste, and of the frustrating bureaucracy of an animal control system we were just beginning to understand.

3.

Rabies is a disease that is unequivocally associated with the dog. It has evolved to take full advantage of a dog’s physiology and habits. It’s perfectly attuned to the dog’s nervous system, and it’s method of transmission, through infected saliva and biting, was perfected, you could say, with the dog in mind. Which would be fine, if the dog had not also been at the same time busily adapting itself to human culture. As Wasik and Murphy put it, “Rabies coevolved to live in the dog, and the dog coevolved to live with us — and this confluence, the three of us, is far too combustible a thing.”

And yet, in this drama, humans are the third wheel. We are what’s known as “accidental hosts”: the rabies virus cannot complete its life cycle in humans alone, mainly because we’re ill fitted for biting, and thus we do a poor job of transmitting the virus from human to human (there have been extremely few documented instances over the past several thousand years of a human-to-human infection). As accidental hosts, we’re largely irrelevant to the rabies virus; as such, it can afford to dispatch us quicker than other hosts, since it doesn’t need us to stay alive long enough to transmit the virus. The disease represents a dance between two organisms, dog and virus, a dance that doesn’t involve us at all.

So controlling rabies in humans means controlling rabies in dogs; in places where the dog population is controlled with respect to rabies, there is little to no rabies whatsoever. This was not immediately apparent; decades after rabies vaccines were being given to humans, dogs were regularly left unvaccinated, particularly in the American South (hence not just Old Yeller and To Kill a Mockingbird, but also Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, where rabies also appears). But since World War II, regular vaccinations of dogs have greatly reduced the incidence both of rabies in dogs and in humans. It has come to be seen, in Wasik and Murphy’s words, as an “archaic holdover from an earlier age: seldom seen, nearly mythical.” Now mostly the stuff of horror stories, like Stephen King’s Cujo or the rabies-inspired zombie film 28 Days Later.

But it hasn’t disappeared entirely. In the United States, the most common carrier of rabies has become, in the last twenty years, the raccoon.

4.

The raccoon is capable of carrying a wide variety of viruses and pathogens, all of which move slowly through the animal’s body, and in rarely hamper its movements or behavior. It’s so well known for its parasites and diseases that two such parasites are named for the raccoon: Gnathostoma procyonis and Baylisascaris procyonis. Adept at functioning no matter what pathogens and other diseases are swirling through its body, there are only two diseases which pose real threats to the raccoon. One is canine distemper, which, in a famous 1968 outbreak, all but wiped out the raccoon population in Clifton, Ohio.

The other is rabies. And in the past few decades it has become the animal increasingly associated throughout North America with rabies, far more so than the dog. Those raccoons imported from Florida to Virginia in the 1970’s, it turns out, happened to count amongst their numbers at least a few rabid specimens. Prior to then, raccoon rabies had not been seen outside of Florida or Georgia, but by the end of the 1970’s it had quickly spread throughout much of the country — including a terrifying outbreak in Manhattan in 2010 that lead to dozens of documented rabid raccoons scourging Central Park.

The raccoon, it would seem, has come to shoulder the burden of the dog’s illnesses. Just as it shares the dog’s “less noble” attributes — dumpster diving, scavenging, and so forth — so too does it share the dog’s receptiveness for these two particularly virulent diseases, and just as we’ve all-but wiped rabies out in dogs, it has fallen to raccoons carry that weight. And so while we’ve banished it from the home, vaccinated our dogs and ourselves, it hasn’t vanished altogether. “Rabies,” Wasik and Murphy conclude, “has receded to become a sort of spectral presence, a ghost story. It’s gone until it isn’t.” Which is to say, it remains out there on the perimeters, the wildness just around the corner, in the dumpsters, in the bushes, watching.

5.

The rabies vaccine schedule in dogs works in two parts. At birth, they’re supposed to get a one-year vaccine; the next year, they get a three-year vaccine, renewing it every three years from then on. Alistair was a rescue, which meant that the pound gave him a one-year vaccine automatically when we picked him up. The following year, we got another one-year vaccination from the vet. That was two years before the attack.

But what exactly that meant — whether it meant that the vaccine had expired or not, no one could really tell us. For forty-eight hours, Nicole and I rushed from vet to vet, anywhere we’d ever taken the dog to get a tick or fox tail removed, hoping that at some point someone had given him an extra rabies vaccination. At virtually each place, we got conflicting advice as to whether those two one-year shots added up to protection. Some vets were convinced that it was fine, that the second shot should have covered him, but usually when Nicole or I pressed them, they began to talk in circles, and none of it seemed convincing enough.

Ultimately, we were told the dog needed to be quarantined for forty-five days, a sort of half-assed measure that suggested above all that they either didn’t know what to do with Alistair or couldn’t be bothered to figure out. Even the quarantine itself was half-assed. Quarantine means isolation, it means removing the animal from the population to make sure that if it is carrying a disease, it won’t transmit it to anything it comes into contact with. However, while “quarantine” was the official word we were given, quarantine was not what happened. The dog was left with us, and we were told simply to keep it out contact with people and other dogs. In other words, it was more or less house arrest, the dog remanding to our custody under its own recognizance. Which from our perspective — and Alistair’s, I’m sure — was far less traumatic, but it didn’t really speak highly of the consistent vision and protocol of Animal Control. Other than charge us a hundred dollars for the privilege of keeping our dog in our own home, the quarantine was a mere formality.

6.

A current popular term describing the dog’s evolutionary strategy is “social parasite,” that is, an animal who has found its best evolutionary strategy to be to endear itself to more a successful, top-order animal — in this case, us. Rather than evolve to be successful on their own, dogs have hitched their wagons to humans, adapating themselves so that we would keep them around. The theory goes that a lot of the dog’s behavior, particularly the mimicking of human emotions, is all a strategy to impress us so we don’t kick them out — particularly now, after their traditional tasks, like herding and hunting and protection, are less important. This theory makes a fair amount of sense, given how successful dogs have proven at keeping their species alive: while their closest relative, the wolf, numbers in the hundreds of thousands, there are close to a billion dogs on the planet.

Raccoons, too, have become social parasites on human culture, though far more unwelcome. They have adapted themselves to live on human refuse, to thrive on our detritus. They are the dark half of the coin, the reverse image of the dog.

On an episode of This American Life, a woman only named “Michelle” described her experience with a rabid raccoon: “the moment the raccoon saw me, it hissed and snarled… The feeling was, all it cared about was attacking me.” The creature jumped her, attaching itself to her leg, and by the time her husband came to her rescue, he had to hit it literally several dozen in the head with a tire iron before it gave up and died. Reflecting on the experience afterwards, she said, “I felt so betrayed by nature. That’s actually how I felt. I felt that nature betrayed me, because I would take walks every day in the woods. And I had never felt threatened.”

That sense of betrayal is perhaps at the heart of a raccoon attack. It’s not just that you’re not expecting it, it’s not just that people don’t really take you seriously, it’s not just the pain and the fear of rabies and everything that comes after. It’s that sense of betrayal by a nature we think we understand and have made allowances for, a nature that had seemed predictable and then suddenly isn’t.

After the attack, someone I knew vaguely, a friend of a friend, responded to my story with the rather sanguine zen comment, “Raccoons are nature’s way of reminding us that humans are not in charge.” As obnoxious as his tone was at the time, he was right, to a point. The raccoon attack was a clear reminder from nature that we weren’t in charge. But that doesn’t really get to the problem here. There are lots of things that can remind us that we’re not in charge: bears, ebola, hurricanes, cancer — there are a host of other unpredictable elements that threaten to undermine our sense of safety and security at any given moment.

Raccoons are different: they are nature, and they are the unpredictability of nature, to be sure — but they are a natural element that is uniquely intertwined with our landscape. They are an element of nature we have made a unique space for, a space vacated by the dog, who left room for this other social parasite, the one watching quietly, intently, in near wilds.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators