Animal Magnetism (4)

By:

August 29, 2016

HiLobrow friend and contributor Colin Dickey is author of Cranioklepty & Afterlives of the Saints, as well as a forthcoming book on haunted houses, Ghostland. HILOBROW is pleased to present a brief series of Colin’s previously published essays regarding animals.

In Near Wilds, Part One

This essay first appeared in Telling Reads.

1.

I turn on my brights when we round the corner into the parking lot of our apartment complex where we’re living now, in Santa Cruz. It’s hard to overstate the beauty here — the redwood trees that erupt out of the parking lot, the lagoon behind our apartment building. On mornings you can see coots and ducks regularly, and occasionally a great blue heron. You can pick the wild blackberries and watch the fog hover ghostly over the water’s surface. Once while walking our dog Alistair along the edge of the water, he startled a heron who took flight, cruising the entire length of the lagoon, just inches above the water. Other times I’ve watched that same heron standing fully upright against the reeds, moving painfully slow while watching the water below for food, a stalking ghost. Nearby at night black waves break against the rocks in their lumbering calm. You can see the iceplant along the cliffs vibrate in the wind like cilia. It’s easy to be lulled into the beauty of this landscape, but I do my best to stay vigilant, I do my best to turn on my brights at night, because now my wife and I both know what lurks here.

They lurk in the hedges, which is where I look first — watching for the radiant green eyes, flat and luminous, lit up by the car’s headlights. They lurk by the trash cans, and at the mouths of the storm drains. They lurk unabashed. They are never hurried, they are never scared. They see you, at best, as a curiosity. At worst, as a nuisance.

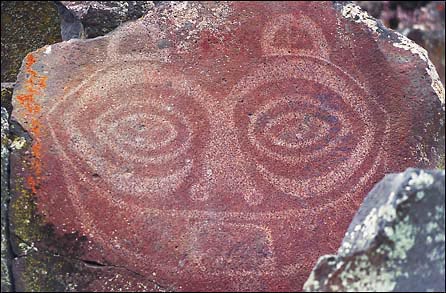

Even as I watch them, they’re watching me. They’re raccoons, this is what they do. Along the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington border, the Yakima have a deity believed to be the land’s guardian spirit, named tsa gag la lal, “she who watches,” or “the watcher.” Its face is that of a raccoon.

2.

The name “raccoon” comes from the Algonquian arakunem, which means “he who washes with his hands.” But most of the raccoon’s other names speak to an animal that seems to lie in taxonomical confusion. Columbus called them perro mastia, “clownlike dog.” The French called them at first chat sauvage, “savage cat,” then le raton laveur, “the rat who washes.” Germans call them waschbarr, “little bear,” similar to its name in Mexico, osita lavenda, “little bear who washes.”

Routinely conflated with other animals, their current accepted scientific name is Procyon lotor, given to them by Gottlieb Conrad Christian Storr. Lotor means “washer”; procyon means “before the dog,” or “early dog.” We approach the raccoon, fundamentally, as a mimic, as a creature that appears like a half-dozen other animals.

It’s not just in taxonomy that we misunderstand the raccoon. The animal’s name comes from a universally observed trait that it washes its food, though this is not, in fact, what it’s really doing. Its strongest sense is touch, and the tactile sensors on its paws are heightened when they’re wet, so it often wets its paws while handling food to better understand it. This and other seemingly playful, childish behaviors they exhibit has led to attempts to keep them as pets: Calvin Coolidge kept a pet raccoon named Rebecca, and Herbert Hoover had one named Suzie. This despite the fact that they are not domesticated, cannot be domesticated.

Perhaps we presume this familiarity because of the raccoon’s facial markings, the distinctive black mask, which helps give the animal a sense of clownishness, or gentle buffoonery. Theories differ on the purpose of the raccoon’s facial markings: they may be to reduce glare (not unlike the blacking under a football player’s eyes), or to act as targets, since the skin around its face is more heavily protected. Or, like the panda, the black mask may be there to make its eyes look bigger, and thus more threatening. But of course, as humans, we don’t see large eyes as threatening — we associate them with kittens, babies, Japanese manga. And so perhaps the real problem is not mistaking the raccoon for a bear or a dog, but mistaking it for a cute, silly animal.

The raccoon, according to zoologist Samuel Zeveloff, “resembles a chubby, affable clown rather than the considerably strong and occasionally ferocious animal that it is.” Introduced into British Columbia’s Queen Charlotte Islands in the 1940s to bolster their fur industry, the raccoons got loose and quickly became widespread, in the process decimating the native population of ancient murrelets. On one island three or four raccoons were responsible for the deaths of dozens, if not hundreds, of these birds — many more than they could possibly eat. Like humans, raccoons can engage in surplus killing, as though for the sport of it, or perhaps just out of boredom.

The raccoon’s violence is not well known, though it is well documented. Take, for example, the ordeal Lisa Wilcox, of Vancouver, went through in August of 2012. Walking her dog down on an alley, she was beset upon by a vicious raccoon, who went straight for her dog. Wilcox grabbed the raccoon, saying later, “It was the lesser of two evils, because it was pretty much going to kill my dog.” Not knowing what else to do, threw it into an enclosed yard after the animal bit into her thumb. The raccoon, undaunted, jumped over the fence and continued to pursue Wilcox and her dog; her cries finally brought five strangers, including one who beat the thing with an umbrella, finally scaring it away.

Wilcox is not alone; that same month, Michaela Lee, of Seattle, was attacked while walking her dog by a gang of raccoons: they chased her for about seventy-five feet, finally knocking her down, and then they set on her. “They were on top of me, just biting my arms and legs and sides,” she said. “I was just trying not to let them get to my face.”

A week earlier, in Eugene, Oregon, Mary Ellen York was attacked — again while walking her dog. (In many of these cases, a dog is somehow involved.) “I just started screaming. Help me, help me,” York later recalled. The raccoon went straight for her dog, and when York was able to get the dog away from it, it went for her instead. Knocking York to the ground, the raccoon bit the back of her knee, then returned to the dog, jumping on its back. “I grabbed the back of his hind leg. I remember twisting them. I grabbed her and was holding on to her for dear life and he kept attacking me. Three times he went to my face.”

These attacks are not common, but those who face them have the added humiliation of being attacked by an animal most people regard as cute and innocuous. “If it was a dog attacking people, or any other animal other than a cute raccoon, people would take it very seriously,” Lisa Wilcox told reporters, noting that others have since told her it was her fault for the attack.

3.

After the incident, my wife developed a dread fear of raccoons. This was the hardest part to explain — even I didn’t get it for a long time. The idea of fearing raccoons seemed to me — seems, to most of us — absurd. They’re not like snakes or spiders or wolves, the normal things one becomes terrified of. There’s no corresponding word like arachnophobia: procyonophobia.

But snakes, spiders, wolves and other dangerous predators will rarely attack humans unless provoked—they prefer to stay well out of the world of human contact. Raccoons don’t have the fear or distrust of humans that larger predators have. They have no fear, no shame. They look at you as though they feel that you are the interloper, that they have more of a right to be in these trash cans, in these manicured hedges, in these storm drains, than you do.

I watch them now, at night, their slow prowl through the concrete and trees of our neighborhood, unfazed by anything that the human world might throw at them. They are not pack animals by nature but they seem to travel in gangs mostly, and their destination seems always to be the dumpsters and exposed trash cans of the apartment complex and nearby homes. The lagoon right behind our apartment would seem to be a natural home for them, since they evolved to prefer arthropods and other small aquatic animals. But since raccoons, like dogs, are among the most omnivorous mammals, and will eat nearly anything, the processed food and other waste that humans throw out nightly has revealed itself to be far easier, and far more enticing. Raccoons can teach their young to eat new cuisine, such as how to crack a melon to get to the meat inside, and they can pass this learned behavior down through generations. (As the naturalist H.B. Davis put it in his 1907 study of the animal, “The raccoon seldom sulks when the table is spread. He never questions the cooking.”)

They lack any kind of honing ability: if you displace a raccoon it will not try to find its way home — they’re forever rootless, moving ever forward. Raccoons are the ghosts of the suburbs. You park on the street in your cul-de-sac, and get out on a warm night, your hands full of groceries, and there they are — at the edge of the road, watching you, assessing you. Last year my wife Nicole opened the front door and saw a line of three of them: fat, unconcerned, working slowly up the sloped roof. The caravan stopped, each one assessing her, before, slowly, they turned back and continued their ascent.

The Dakota call the raccoon wee-kah teg-alega, “sacred one with painted face.” Aztecs called female raccoons see-oh-at-la-mas-kas-kay, “she who talks with gods.” Cubs they called ee-yah-mah-tohn, which translates as “little old one who knows things.” When they watch you, they give off a preternatural sense that they know more than they’re telling, that they look back at you as an equal, or see you as inferior. This too, is perhaps anthropomorphizing. But to what degree, I can’t say.

4.

Raccoons prefer wooded areas near sources of water; a floodplain forest is their ideal habitat, but raccoons have proved enormously adapted to human environments. They can make dens out of abandoned barns, corn cribs, and firewood piles. They positively thrive in urban environments. The human has proven consistently able to provide the raccoon with its needs; not just dumpsters and their easy cornucopias; among the food they’ve learned to eat are maimed and crippled geese and ducks left for dead by hunters.

They have become intertwined with human populations in other ways as well. For much of the century, raccoons have been the most economically important fur bearing animal for the United States. Some figures, from Junius Henderson and Elbert L. Craig’s 1932 Economic Mammology: in 1913 it was estimated that 600,000 raccoon skins were sold, averaging about $4.50 each. By 1919 that number was up to 1,713,700 skins. In February 1920, in St. Louis, 73,000 raccoon pelts were sold, as compared to 130,000 the previous year. 393,000 were exported from the United States in 1925. In New York, a trade show in January of 1928 recorded raccoon pelts selling for a high of $15.00 a pelt (for good condition Eastern raccoon) and a low of $.10 for low quality Florida raccoon pelt.

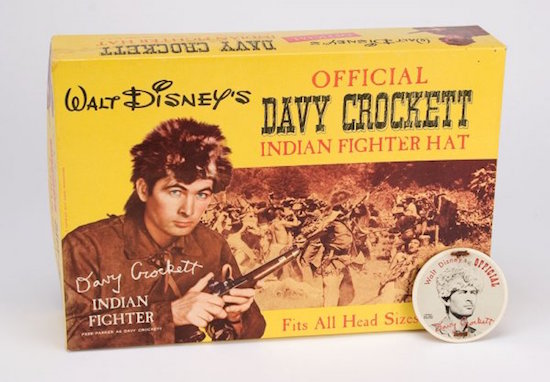

This appetite for raccoon pelt has only continued, buoyed occasionally by coonskin cap fads, such as that among collegiate men in the 1930’s, and, more visibly, that started by Disney’s Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, in the 1950’s. (For the record, the cap that Fess Parker, the actor playing Crockett, wears is actually a mix of badger and coyote.) Additionally, unscrupulous traders have sometimes marketed raccoon fur as either “Alaska bear” or “Alaska sable.” Nor did raccoon pelt hunger die out after the 1950’s; in 1982 alone, sales of raccoon pelts reached $100 million.

Because of this, we have helped spread them throughout North America. Periodically, raccoon hunters or furriers have occasionally imported raccoons, as in the 1970s, when raccoon hunters in Virginia imported thousands of raccoons from Florida, or, of course, the vicious killers that were imported into the Queen Charlotte Islands and which soon ran amok. Their population grows quickly; since the depopulation and control of their main animal predators — coyotes, bobcats, and occasionally wolves — raccoons have emerged as a rather unlikely top-order predator. We have, in effect, elevated the raccoon to our own status, as one of the few animals on this continent without any real natural predators left.

Curiously, their bodies have become useful barometers for human culture in another way. A few years ago, the Department of Energy’s Savannah River Nuclear Site captured and dissected numerous local raccoons to measure the amount of radiocesium that had accumulated in the animals’ bones and soft tissue. What the raccoon finds in dumpsters is not the only source of human detritus that it takes into its body; between the isotopes in its bones and the trash in its gut, the raccoon is a walking, scavenging geological record of our civilization’s waste products.

5.

Our apartment is on the second floor; the building has four units, front and back lower and front and back upper. You go up an exterior flight of stairs to a landing for both upstairs apartments. This also means that this flight of stairs is the only way out of the apartment. The morning of the incident, I was in Los Angeles, there to give a lecture on Lady Chatterly’s Lover. Nicole was teaching at 8 a.m. that semester; normally, on those days she has to teach that early, I walk the dog after she’s left, whenever I get up. But because I was out of town, she had to walk him herself, which meant getting up an extra half hour earlier, which meant getting up at 6 a.m., which meant walking him in the dark.

At the time, there was a trashcan at the bottom of the stairs. A trashcan, the kind of innocuous gesture of an apartment complex management that wants to keep its grounds clean so that the overall feel of the place is enjoyable, pleasant. It was here, on that morning, when Nicole took our dog Alistair out for a walk, that she found two raccoons gathered around the trashcan, rooting around for whatever detritus had been left behind. And when he saw them, Alistair started barking.

6.

Our dog barks too much, too often, for no reason. It’s the result, as it happens, of a millennia-old habit which has, by and large, outlived its usefulness. Alistair’s herding instincts, his protection instincts, his ability to fetch, all stem from previously useful skills that are no longer particularly relevant. Dogs today are just a hodge-podge of leftover traits, the remnants of the mysterious process of domestication — the origin of which remains one of the more fascinating unanswered questions in human civilization. We’ve come a long way, through DNA analysis and archeology, towards providing possible answers to that question, but as Mark Derr, author of How the Wolf Became the Dog, himself admits, “Absent hard proof, all anyone has are theories of varying degrees of plausibility.”

One popular, long-standing theory was that the dog is actually descended from two different sources: the wolf and the jackal. This was maintained by, among others, Freud himself, who saw in the wolf all of the dog’s more noble traits (sociability, hunting, cunning, judgment), and saw in the jackal the dog’s baser traits (scavenging, excrement-eating, dumpster-diving). There’s no DNA evidence for the jackal’s influence on the domesticated dog, but the suggestion helps separate out these two halves of the dog: the high and the low, the pure and the unclean.

Derr’s own theory is not that humans domesticated the dog through the wolf, but that the dog more or less gradually but spontaneously mutated from the wolf, just at the moment when these new traits were particularly advantageous to humans. But even he is equivocal on a final answer: “The search for the first dog seems always to lead to more questions, to dissolve into a ghostly visage leaping just out of grasp. The dog remains a hint, a whispered rumor in the genetic code, an inexplicable fossil, before it seems to arrive full blown upon the scene, a gift from the gods or a god itself — or more.”

The frustration at our inability to understand the dog’s origins reflects, in some ways, our frustration to understand our own ancestors. We can catch glimpses on how we developed tools, how we bested our rivals like the Neanderthal, but how we developed the most complex tool of all — the genetic manipulation of an animal into another species, one exclusively useful to us — remains elusive, and with it, the basic understanding of our earliest ancestors.

Equally frustrating — or perhaps fascinating — is the fact that this domestication was never fully completed, nor will it ever be. The German novelist W. G. Sebald writes of the dog, “His left (domesticated) eye is attentively fixed on us; the right (wild) one has a little less light, strikes us as averted and alien. And yet we sense it is the over shadowed eye that sees us.” No matter how reliable and affable a dog is, there’s always a tinge of that alien wildness in him, it never goes away. It’s why there are far more cases of dog bites than any other animal attack in the United States each year — that wildness we’ve brought into our homes, that we can domesticate but never quite tame, that watches us always. Nor is this always a problem; it’s that mix of the wild and the domestic, Mark Derr suggests, that makes the dog so very valuable to us. “The dog bridges these worlds; indeed, the dog lives in the border zone between states. That is a major reason dogs are so valuable in our lives — they connect us to a world outside ourselves and our categories.” But there are moments when this wildness explodes suddenly, terrifying your world into a new and horrific reality.

7.

Wolves will sometimes bark, growl, and make other noises in order to confuse and distract their prey — forcing herd animals to bolt or charge, so that the pack can then single out the young or the weaker animals. It’s possible, then, that Alistair was trying to distract the raccoons, perhaps so Nicole could then get the jump on them. Maybe the problem was that she failed her part of the plan.

He is a mutt, mostly black lab but mixed with something small, the net effect being he looks like a half-sized lab, weighing only forty pounds. In many ways this is ideal, since he has a number of endearing lab-like qualities, without being the massive lumbering beast that would destroy an apartment or small house. But it also means that he perhaps thinks he’s a bigger deal than he really is, and while he can unleash a ferocious torrent of barks at an enemy, he doesn’t have the heft to back any of this up.

While she stood there with Alistair on a leash, one raccoon did the unthinkable: it separated from its mate, and broke towards Nicole and the dog. In an instant — in one of those horrifying instants in which everything seems suspended even as it’s happening—the thing was attacking Alistair. It jumped on the dog’s back, snarling and tearing into the back of his neck, while he tried to get around to get at it. Nicole, stunned for only a moment, then tried to kick it off — at which point the raccoon turned and attacked her, sinking its teeth fully into her left calf.

I’ve heard stories since then — of raccoons disemboweling dogs twice their size, or a man who hung from a tree for dear life one time by holding on to a raccoon’s tail, the forty-pound animal supporting both of their weight — stories of preternatural strength and ferocity, stories that make it difficult for me to try to reconstruct those moments, knowing how terrifying they must have been for both Nicole and the dog. At some point she finally just let go of the leash and ran back into the apartment, calling Alistair, who broke free and ran to her. Miraculously, the raccoon didn’t follow. It disappeared and by the time Nicole ventured out again, it was gone for good, into the wild and the coming dawn.

By the time I awoke, it was already over. I didn’t even have to listen to the message — perhaps I didn’t want to, didn’t want to hear that voice of panic. But I saw the photo Nicole had sent me, of her leg, already purple-red bruised, punctuated by four bright red puncture wounds from the raccoon’s teeth. The dog, she told me when I talked to her that morning, was okay. She still had to teach; I’d caught her right before class was beginning. She was shaken up, bruised and traumatized, but otherwise mostly okay. I offered to come home, but we decided that it probably wasn’t worth it. Only after I hung up did I start to realize that the bites were just the beginning. The real problem was what might have been in that raccoon’s saliva, what may have been in the wound.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators