Animal Magnetism (3)

By:

August 28, 2016

HiLobrow friend and contributor Colin Dickey is author of Cranioklepty & Afterlives of the Saints, as well as a forthcoming book on haunted houses, Ghostland. HILOBROW is pleased to present a brief series of Colin’s previously published essays regarding animals.

Shooting Animals

This essay first appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly.

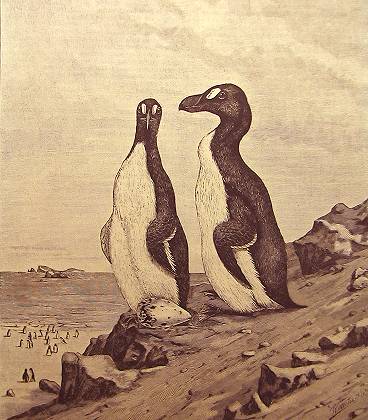

The last pair of great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was killed in 1844 on the desolate Icelandic island Eldey, hardly more than a flat rock jutting up above the waves. The large, flightless bird had been hunted for centuries, first for their meat and then for their feathers, which were used in down pillows. In 1794 one seaman described with casual disregard the process of collecting the auk’s feathers: “If you come for their Feathers you do not give yourself the trouble of killing them, but lay hold of one and pluck the best of the Feathers. You then turn the poor Penguin adrift, with his skin half naked and torn off, to perish at his leasure.” As their numbers dwindled, collectors and museums began rushing to kill, preserve, and mount the few remaining specimens. Three sailors employed by a wealthy merchant who’d wanted some examples preserved and stuffed found the last pair incubating an egg; the sailors strangled the two birds, then smashed their egg underfoot.

That same year, William Henry Fox Talbot published his The Pencil of Nature, the first book of “photogenic drawings” — what he came to call the calotype, one of the earliest forms of photography. Both photography and the extinction of animals, in their own ways, are by-products of industrialization and the modern age. Photography needed not just the wealth of chemical knowledge and scientific discovery that drove the early 19th century, but also its newfound fascination with mechanization: Fox Talbot, in his introduction, wrote how his images are formed “without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil,” formed by “optical and chemical means alone.”

Extinction, too, depends on the modern era. In order to even come to understand extinction, we first need taxonomy itself: scientific cataloging, records and inventories — not just the mechanized slaughter of whales and other species, nor the habitat destruction that comes with development. To understand that a thing is gone, one must first know what it is, know how it is different from similar animals that remain. Only when we exhaustively and minutely catalog the animals around us can we begin to understand that some of them — many of them — are disappearing from sight.

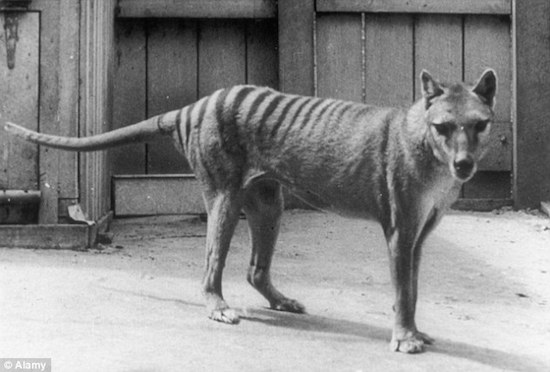

Errol Fuller’s Lost Animals brings together in uncanny convergence these two facets of modern life. The book collects photographs of now-extinct species, from the thylacine (the Tasmanian tiger) to the pink-headed duck to the laughing owl — species that are now gone but that have left behind photographic traces. A catalog assembled from both accidental snapshots and deliberate attempts to document vanishing animals, Lost Animals offers a lens into a peculiar kind of record — a photo album as ephemeral as the animals inside.

Some images stand as rare treasures, glimpses of elusive species that were caught on film only a few times before disappearing entirely. Extinction, after all, is itself about vanishing, about leaving no trace, and many of these photographs reveal a story unto themselves — a story about the impossibility of photographing animals. The endless quest to document the ivory-billed woodpecker is one example — a species so elusive that ornithologists are reluctant to definitively declare it extinct. Many of these animals went extinct before modern camera photography allowed high-speed exposures and telephoto lenses, when photography was a painstaking process that didn’t reward the flitting movements of a scarce bird.

But not all of the animals in Fuller’s book were inherently camera-shy. There are also species here that once were ubiquitous, and yet almost no images of them remain; the fact that so few images exist of formerly numerous species suggests the lack of interest we once had toward them — animals that only became noteworthy and interesting once they had vanished forever.

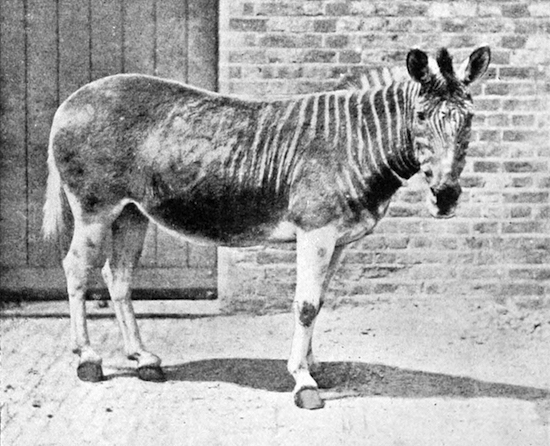

In his introduction, Fuller notes that “a photograph of something lost or gone has a power all of its own even though it may be tantalizingly inadequate.” That is, unfortunately, as deep as he’s willing to go into the reasoning behind this book. Fuller isn’t interested in delving into why photographs exert a pull on viewers in a way different than other forms of illustration, and he’s not interested in asking exactly why a photograph of an extinct quagga might resonate differently than a photograph of a zebra. While the sparseness of the photographs creates an allure and a pathos to the animals, the paucity of text is more frustrating. The large type, scanty descriptions, and simplified narrative at times make the book feel as though it’s directed toward middle-grade readers.

But while that’s unfortunate, it doesn’t in the end matter much. The photographs in Lost Animals are compelling: the animals in these pictures resonate powerfully with a natural melancholy, even if they themselves don’t understand that their days are coming to a close. At one point Fuller apologizes for the quality of some of the images, and then suggests that a low-quality, blurry photo of a now-departed species may “in its own way” be “full of atmosphere, even poignancy.” This is a bit of an understatement; it is of course precisely the imperfect aspect of many of these images that gives them their power, in particular, the numerous species represented here who spent their final days in zoos: the quagga, the thylacine, the passenger pigeon. As John Berger points out, when you look at animals in a zoo, “you are looking at something that has been rendered absolutely marginal; and all the concentration you can muster will never be enough to centralise it.” The zoo animal is always, for Berger, “like an image out of focus.” The same could be said for a photograph of any extinct species, both in and out of focus. The thylacine and the quagga fade into the blur and the grain of the image, as if we are glimpsing them not in a photograph but through some distant veil of nature.

(Even the professionally shot images, such as the ones taken by National Geographic photographer David G. Allen of the Atitlán giant grebe, are disturbing: the clarity of which serves only to remind us that these creatures disappeared in our own age, within the lifetimes of many of us.)

As the general attitude in the first world has moved away from wanton killing and toward preservation, the camera has neatly replaced the gun — a transference so seamless that much of the terminology itself remains intact. In Cyril H. H. Jerrard’s description of setting up his photograph of the paradise parrot, he repeatedly emphasizes the analogy to hunting:

A small aperture at the front formed a loophole through which the photographic ‘gun’ was ‘aimed.’ These preparations for bloodless ‘shooting’ were made about noon. … The male approached the nest hole, just where I wished him to pose, uttered a sweet inviting chirp to his mate and peered into the hole. In answer … the female alighted on the summit of the mound … I ‘fired’ again, both birds posing for just the instant required.

At the time Jerrard was writing in the 1920s, these terms were still relatively novel: advances in camera technology had only recently led to a stronger connection between the camera and the gun. The use of the verb “to shoot” to refer to cameras came into being only in the 1890s, according to the OED, the same decade that saw the birth of a new sport: “camera hunting,” the main object of which, according to one advertisement, was “to bring about the renunciation of the gun for the camera; and it is hoped that it will be an effective means of discouraging the unnecessary slaughter of the birds and other wild animals of America.” George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream, who’d once been called the “father of American conservation” by The New York Times, founded the sport of camera hunting. Grinnell had long advocated “gunless hunting,” his term for simply strolling through nature in search of animals, but he also recognized that such activity didn’t produce a trophy, and thus introduced “camera hunting.” “The wild world is not made the poorer by one life for his shot,” Grinnell wrote of his new sport, “nor nature’s peace disturbed, nor her nicely adjusted balance jarred.”

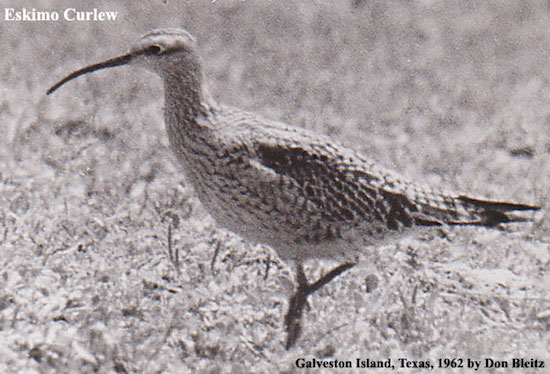

It’s easy to see how contemporary nature photography is a similar activity to the hunting of the 19th century: the attitude toward the pursued animals has changed significantly but remains in many ways very much intact. (As Matthew Brower notes in his discussion of camera hunting, many camera hunters killed their subjects, either before, after, or during the photoshoot: “It seems that the difference between early animal photography as hunting and straightforward trophy photography was a matter of whether the image was taken before, during, or after the moment the animal was killed.”) The line between killing and photographing is always slightly blurred — there is always a confused relationship to preservation, always the tinge of death. “Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art,” Susan Sontag writes. “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability.” Perhaps because of this, the images of Eskimo curlews in Fuller’s book are particularly unstable. Photographed by Don Bleitz in April 1962, the images would seem to show the last remnants of the migratory species running through the prairie grass on Galveston Island in Texas. But Bleitz’s images, Fuller suggests, may not have been living animals but taxidermied specimens poised to look alive. (Frustratingly, Fuller doesn’t give us much more information on these allegations or their veracity.) And how might we tell the difference anyway? Like taxidermy, photography is the art of suspended animation, the arresting of movement into a single moment that’s forever frozen.

Like the taxidermist, like the photographer, the preservationist too wants to stop time in a single moment — to freeze the advance and destruction of humanity, to put a stop to the forward drift of extinction. But the animals themselves have no such preciousness about them; among the reasons for the extinction of the Atitlán giant grebe, Fuller notes, is that they interbred with other species of grebe — if habitat destruction was the main culprit behind their decline, they themselves sealed their coffin, mating themselves into oblivion.

The fixation on saving a species that itself was busy hybridizing itself into a new species reveals the limitations of our thinking. Nature is not precious with its creatures. Meanwhile, we hope to freeze and preserve the taxonomic world exactly as we have found it, or rather at the moment that we named it — as though one could take a photograph of the natural world at a single moment and have it remain undisturbed.

Of all the extinct animals, few are as iconic as the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), whose extinction ranks behind perhaps only the dodo in terms of its notoriety. The bird’s name derives from the French passager, to “go by fleetingly,” but as contemporary accounts of the great flocks of passenger pigeons attest, there was nothing about this animal — at least in its heyday — that was in any way fleeting.

The pioneering ornithologist Alexander Wilson gave one account of the immensity of passenger pigeon flocks at the dawn of the 19th century. One afternoon near Shelbyville, Kentucky, Wilson was overtaken by a flock of passenger pigeons

in such immense numbers as I never before had witnessed.… They were flying with great steadiness and rapidity at a height beyond gunshot in several strata deep, and so close together that could shot have reached them one discharge could not have failed of bringing down several individuals. From right to left, far as the eye could reach, the breadth of this vast procession extended, seeming everywhere equally crowded.

Wilson stopped and decided to observe the flock, to see how long it would take for it to fly overhead. He waited over an hour, “but, instead of a diminution of this prodigious procession, it seemed rather to increase both in numbers and rapidity,” and three hours later “the living torrent above my head seemed as numerous and as extensive as ever.” Wilson later attempted to calculate the number of birds he’d seen:

If we suppose this column to have been one mile in breadth (and I believe it to have been much more), and that it moved at the rate of one mile in a minute, four hours, the time it continued passing, would make its whole length two hundred and forty miles. Again, supposing that each square yard of this moving body comprehended three pigeons, the square yards in the whole space, multiplied by three, would give two thousand two hundred and thirty millions, two hundred and seventy-two thousand pigeons — an almost inconceivable multitude, and yet probably far below the actual amount.

John James Audubon likewise calculated the numbers of passenger pigeons based on flocks he’d seen, coming up with a similarly mind-boggling number of 1,115,136,000 birds flying overhead at once — an experience in which Audubon describes the “light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse.”

How then, did they disappear, and disappear so quickly, almost without warning? In numbers this vast, the passenger pigeon was widely considered a pest, and pigeon shooting contests were widespread throughout North America in which tens of thousands of birds were routinely killed in a matter of hours. But this alone does not entirely explain the pigeon’s extinction; rather, prevailing theories suggest, the social passenger pigeon could only exist in massive flocks, and so once its numbers were thinned to the millions and hundreds of thousands it began a downward spiral, unable to maintain its population without the billions that had once covered the sky.

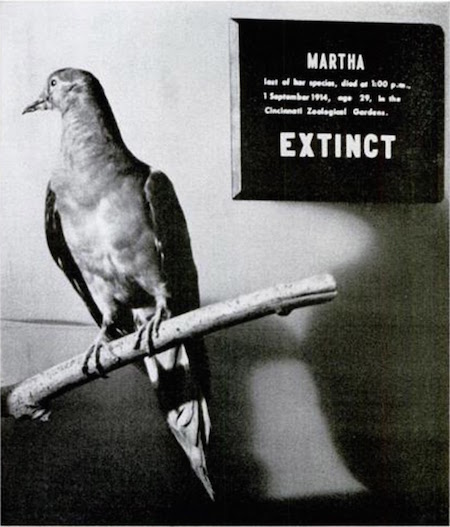

This spectacular reversal of fortune helps explain in part why the passenger pigeon became emblematic for extinction. But there is also Martha. By 1909, there were no passenger pigeons left in the wild, and only three in captivity, in the Cinncinati Zoo — including Martha, who outlasted her two male companions to become the last passenger pigeon alive. Martha’s final days were so well documented, down to her last day, September 1, 1914, that the passenger pigeon’s story has become about more than just extinction: it’s a morality tale, a parable of human conquest and expansion, a fable about the European conquering of these United States and the unexpected toll we exacted on the land and its animals.

Less than a year after Lost Animals, which itself features a chapter on the passenger pigeon, Fuller has published a second book entirely devoted to the iconic bird, timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of Martha’s death. As with Lost Animals, the text of Fuller’s The Passenger Pigeon is brief and at times unsatisfying, giving only a short overview of the life and demise of this spectacular animal. The book contains an appendix of quotes about the passenger pigeon, and while they’re illuminating, they reinforce an incomplete feeling about the book, as though it’s meant as more of a sourcebook for someone who wants to write a better narrative of the bird than a book unto itself. (Also included is a bibliography of books that Fuller argues are far better than his on the subject of the pigeon.) Fuller’s own The Passenger Pigeon, he explains in the introduction, is more of a simple “celebration (perhaps an inappropriate term in the circumstances), in both words and pictures, of the former existence of the Passenger Pigeon.” With its large type and copious illustrations, it acts as a colorful tombstone for Martha and her billions of deceased ancestors.

While it’s lavishly illustrated, the images are themselves hardly as compelling as the grainy, enigmatic photographs of Lost Animals. From period watercolors to contemporary artists’ takes on the passenger pigeon, we get a wide sampling of its influence in American art, but few of the images have the melancholic stature of the uncredited photographs of Martha, alone in her cage at the Cincinnati Zoo. The lone exception, of course, is the striking image of two passenger pigeons by Audubon himself — the gray and green female leaning down from a branch to feed a beautifully plumed male, his scarlet underside giving way to blue wings. Of all of Audubon’s famous images, this one is singular in its beauty, its elegant grace.

But it is also inaccurate: Fuller writes that Audubon’s

positioning of the birds does not reveal how they would typically have behaved, rather the opposite. The picture is an artificial construct rather than the strict portrayal of truth so favored by most wildlife artists. It would have been normal for Passenger Pigeons to perch side by side on a branch rather than one above the other.

Audubon’s pose was often adopted by later illustrators, perpetuating the error, leading naturalist Robert Wilson Shufeldt to later argue that “in technical ornithological works the portraits of birds should never be shown in unusual poses or performing some action.” Once you depict birds in some specific pose, you run the high risk of introducing an error — too many images of the passenger pigeon, beginning with Audubon, have distorted its nature and its purpose by animating them according to the aesthetic desire of human eyes.

But then, depicting the bird as Shufeldt suggests, stock-still and devoid of context, is in its own way just as unnatural, just as misleading. If Lost Animals is about the photographs, much of this book is about the failure to accurately represent passenger pigeons. Fuller singles out a display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, for example, featuring a dozen or so taxidermied pigeons, stately on bare branches surrounded by autumn foliage — regal, watchful. Despite the obvious care and high-quality touches of the display, Fuller points out, it’s factually erroneous, as passenger pigeons never would have been able to survive in such sparse clusters. An accurate diorama would not show a few well-preserved birds on barren branches but millions of taxidermied birds flooding the rafters of the museum. So, too, then, with the photographic record, which shows not the bird in its natural habitat, blotting out the sky, but only solitary examples — forlorn and alienated pigeons who linger on the other side of their great apocalypse.

Even the attempts by Wilson and Audubon to count their numbers, based on approximations and guesses, fail to capture the true extent of the pigeon, and still today we can only grasp at understanding its range and numbers. The passenger pigeon, despite its once-vast numbers, has become invisible. All the eyewitness testimonies, all the lithographs and watercolors and digital renderings can never again be seen or understood as it was in life — legion, the very definition of infinity itself taking flight across the skies. Fuller’s book is, in the end, about our incomprehension of the passenger pigeon, an image scarcely glimpsed as it goes fleeting by.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators