Animal Magnetism (1)

By:

August 26, 2016

HiLobrow friend and contributor Colin Dickey is author of Cranioklepty & Afterlives of the Saints, as well as a forthcoming book on haunted houses, Ghostland. HILOBROW is pleased to present a brief series of Colin’s previously published essays regarding animals.

At the Edge of the Map

This essay first appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly.

The Arctic archipelago of Svalbard is largely desolate, with just a few thousand people spread across its bleak terrain. The main settlement is a town called Longyearbyen; at just over 2,000 residents, it’s the northernmost town in the world over 1,000 people. Once it was a thriving coal settlement; now the decaying wood ruins of past mining operations hover like ghosts over the town, which has largely become a tourist hub, home to a cruise ship terminus, hotels, museums (including one devoted entirely to aeronautical attempts to overfly the North Pole in balloons), and, further into the valley, an art gallery, where I found, on exhibition during my stay there, a collection of old arctic maps — filling three rooms, they laid out the sporadic evolution of how we have come to know the Arctic Circle, from medieval maps that presumed fictitious islands and continents based on hearsay, to early modern projections that were both more detailed and more honest in their ignorance, carefully drawn coastlines eventually giving way to indistinct outlines and then to white space, legended “The Frozen Sea,” or “Parts Unknown.”

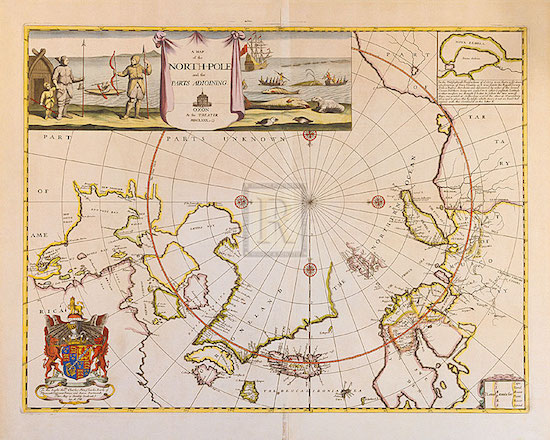

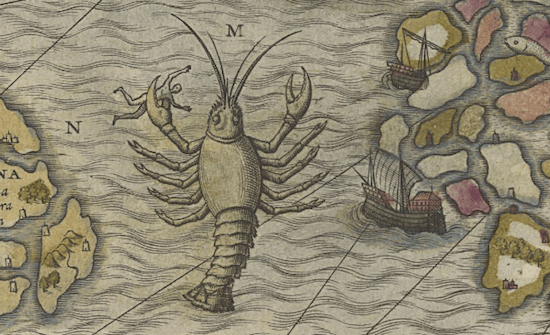

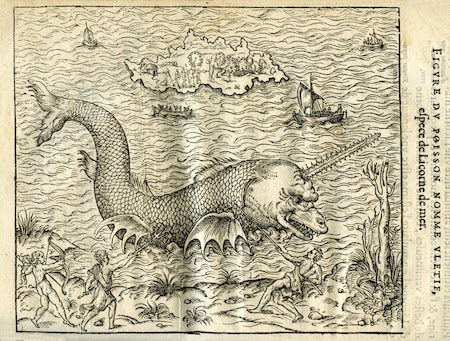

In want of something to fill these blank spaces, mapmakers added flourishes and illustrations, including elaborate scenes around the edges of these maps. In one labeled “A Map of the North-Pole and the Parts Adjoining,” trappers and whalers hunt sea creatures somewhere between whales and walruses; in another a bearded cherub points to a name “Spitzberga,” emblazoned on a shield in turn supported on a pair of whiskered fish. Above the legend of a map of Novaya Zemlya, a hunter pulled on a sledge by a leaping reindeer takes aim with his bow at a rearing bear, while below him men carry dead walruses like sacks of potatoes and a woman milks horned goats. Others still have darker images: not just idyllic scenes of hunter and prey, but strange lion-headed fish, scaly whales with dual blowholes, and on one, a walrus with a human face and hair: a “seamorce,” described as “bigg as an oxe.”

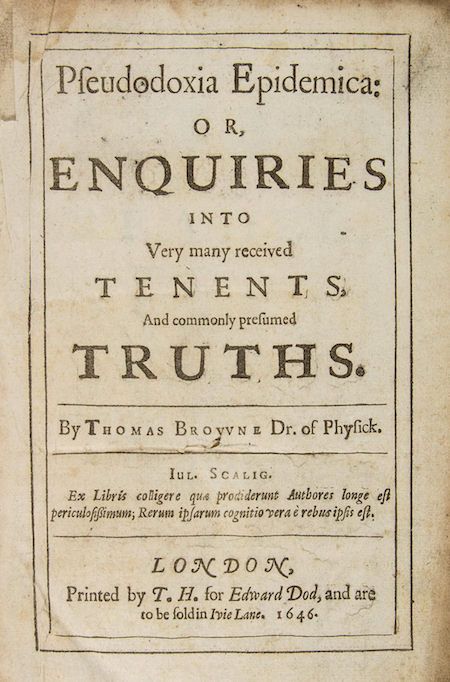

Among those who took aim at these fantastical beasts was Sir Thomas Browne, who sought to dispel myths and longheld errors in his encyclopedic Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–1672). Writing, for example, of Sea-horses (meaning not the small fish in the genus hippocampus but full-sized, aquatic horses often depicted in atlases), Browne comments that they “are but grotesco delineations, which fill up empty spaces in Maps, and meer pictoriall inventions, not any Physicall shapes.” The monster, he suggests, is the illustrator’s equivalent of the cartographer’s “Parts Unknown.” A century after Browne, Jonathan Swift made a similar comment in his 1733 lyric “On Poetry: A Rhapsody”:

So Geographers in Afric-Maps

With Savage-Pictures fill their Gaps;

And o’er unhabitable downs

Place Elephants for want of Towns

It’s true that these animals and monsters may be mere decoration and fantasy, but they’re nonetheless captivating. I have always been far more intrigued with these strange shapes and figures, with these seeming afterthoughts, the marginalia at the edges of the main text, than with the actual content that I’m supposed to be focusing on. For some time I’ve studied the marginalia of medieval manuscripts: the way monks and other copyists would decorate holy scriptures and other literature with bawdy images of nuns breastfeeding monkeys, mer-creatures shooting arrows into men’s asses, rabbit funerals in which foxes acted as pallbearers. The images on the maps in Svalbard weren’t quite as inscrutable, but they did work to interpret the landscape differently than the maps they adorned, telling a narrative story alongside a spatial translation of the world.

This kind of marginalia is for the most part long dead. On a webpage, there may be images, ads, or other visual interference — but there’s not the same sense of empty space that needs filling, the need to doodle away the white void that’s left over. A webpage is always exactly as big or as small as it wants to be. The thing about a printed page, or a map, on the other hand, is that sometimes it has extra space, and what artists have chosen to put in that space often says a great deal, as the visual ornamentation becomes a means of framing the information and directing the eye.

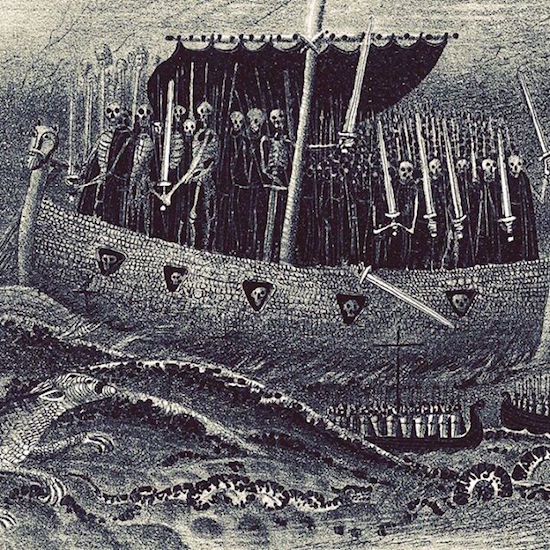

The next day we left Longyearbyen aboard a ship that would take us up the western coast of Svalbard. I was there in the company of twenty-five other artists, writers, and scientists, as part of a residency, The Arctic Circle; for two weeks we lived on a three-masted sailing ship that took us through fjords and open water in a barely inhabited world. During that time I thought some of Naglfar, the nail ship: described in the Prose Edda, it is a ship of from Hell, made from the finger- and toenails of the dead. At the End of the World the Wolf Skoll will swallow the sun and his brother Hati the moon, and the stars shall vanish from the sky. In the midst of a cataclysm, the Naglfar shall be set loose and bring the dead to the land of the living for the great and final battle. As the Prose Edda warns, “if a man die with unshorn nails, that man adds much material to the ship Naglfar, which gods and men were fain to have finished late.” I also thought of monsters, of how ancient sailors looked at the backs of whales, the remnants of squid, or perhaps a narwhal tusk, and saw in them horrors, terrifying menaces. As we sailed out into open waters, into an endless barrage of punishing waves that sickened half the passengers, I thought of those horrible creatures lurking in the open white of those old maps, a warning to other mariners of what lay out there. The images that I’d seen framing those ancient maps had begun, you could say, to frame my voyage as well, and I carried those maps in my mind for the next few weeks, attempting to superimpose their gridded and mathematical lines and their grotesque monsters onto the slate gray and formless arctic sea before me.

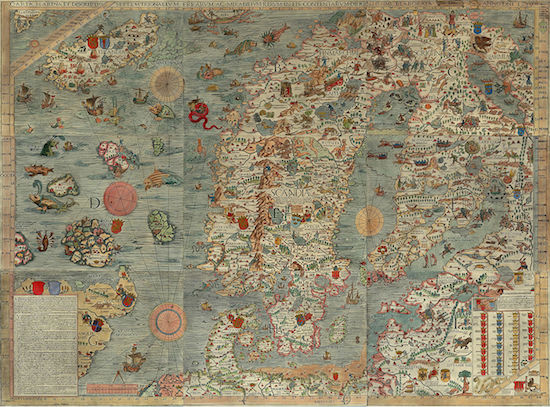

Among the most fascinating examples of these maps, covered with all manner of fantastical creatures, is Olaus Magnus’s Carta Marina. Born in Sweden in 1490, Olaus, a Catholic priest, was working abroad in Gdansk when, in 1527, Protestants overtook his homeland, resulting in his permanent exile. Olaus eventually settled in Rome, and in time would be made the last archbishop of Uppsala (a largely ceremonial title since he could not return to Sweden). Working as something of a cultural ambassador from Scandinavia, he wrote in exile, recreating his home in his writing and his great map.

Olaus’s map is huge — one of the largest charts in both physical size and the scope it covered. It was lost for centuries, until discovered in 1886 by Oscar Brenner (a second copy, the only other extant, was found in 1962). The intervening time did not serve it well; twentieth century scholars have long faulted Olaus’ cartographical ignorance, and his placing of the Arctic Circle at 90 Degrees, rather than at 66. As one critic wrote in 1949: “The map is an interesting example of a compiler failing to understand the character of his materials, and falling into an error which was perpetuated by his successors. Important as was Olaus’ work as the historian of the north, he scarcely emerges from a critical examination as a cartographer of great competence.”

But to look to Olaus for scientific accuracy may be to miss the point. In 1555 he produced his other great work, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (“A History of the Northern Peoples,” literally the “People Under the Seven Stars,” meaning the constellation the Big Dipper). In it he offered the first serious discussion of snowflakes, of which he wrote: “it seems more a matter for amazement than enquiry why and how so many shapes and forms, which elude the skill of any artist you choose to name, are so suddenly stamped upon such soft, tiny objects.” Olaus was as much interested in amazement as competence, as much interested in wonder as in accuracy.

Joseph Nigg’s coffeetable exploration of Olaus’s map, Sea Monsters: A Voyage Around the World’s Most Beguiling Map, refocuses our attention away from the traditional function of the map, pulling the monsters out of the borders and into the frame. It is, for Nigg (“one of the world’s leading experts on fantastical animals,” according to his bio) the geography and cartography that becomes inessential; the “map” he’s interested in is not of land but of beasts. Nigg traces an imaginary voyage through Olaus’s heavily populated seas, past a Polypus (a “Creature with many feet, which hath a pipe on his back… with his Legs as it were by hollow places, dispersed here and there, and by his Toothed Nippers, he fastneth on every living Creature that comes near to him, that wants blood”), a Sea Swine (“it had a Hogs head, and a quarter of a Circle, like the Moon, in the hinder part of its head, four feet like a Dragons, two eyes on both sides of his Loyns, and a third in his belly inkling towards his Navel; behind he had a Forked-Tail, like to other fish commonly”), a Prister (a “kind of Whales, two hundred Cubits long…very cruel. For to the danger of Sea-men, he will sometimes raise himself beyond the Sail-yards, and casts such floods of Waters above his head, which he had sucked in, that with a Cloud of them, he will often sink the strongest ships, or expose the Mariners to extream danger.”), and the terrifying Ziphius (“He hath as ugly a head as an Owl; His mouth is wondrous deep, as a vast pit, whereby he terrifies and drives away those that look into it.” His Eyes are horrible, his back Wedge-fashion, or elevated like a sword; his Snout is pointed…. It will swim under ships, and cut them, that the Water may come in, and he may feed on the men when the ship is drown’d.”). Each monster is given not only Olaus’s description, but an inquiry into Olaus’s inspirations, as well as the subsequent legacy.

The Polypus, for example, is drawn as a fifteen-foot lobster, but Nigg notes that its description more closely resembles an octopus. This is what makes Olaus’s map (and, by extension, Nigg’s book) so fascinating: for all its basis in medieval bestiaries, the map is also a serious attempt to catalog the denizens of the deep. Olaus relied on oral legend, folklore, and his own memories, all of which he gathered and reported as faithfully as he could — a Brother Grimm of oceanographic mythology. As Nigg points out, “Regardless of how fantastically the creatures are portrayed on the map, they are meant to represent actual marine animals.” And at least some of them do: Olaus’s map contains perhaps the first image of a whale nursing her calf; the first depiction of a real oceanographic feature, the Iceland-Faroe Front; and the first mention of a narwhal, albeit under a different name: “The Unicorn is a Sea-Beast, having in his Fore-head a very great Horn, wherewith he can penetrate and destroy the ships in his way, and drown multitudes of men. But divine goodnesse hath provided for the safety of the Mariners herein; for though he be a very fierce Creature, yet is he very slow, that such as fear his coming may fly from him.”

In terms of the narwhal’s behavior, Olaus was mostly wrong — it does not attack mariners, nor is it that slow, but while we know more than Olaus did, we don’t know that much more (“We know more about the rings of Saturn than we know about the narwhal,” Barry Lopez writes in Arctic Dreams). We don’t even know much about the name we gave it — many claim that the word “narwhal” means “corpse-whale,” so named for the animal’s pale color, as though of a dead body, but Lopez and others dispute this etymology. What’s clear is that, with the male’s unicorn tusk, growing as long as nine feet in length, it seems to defy all our standard rules of animal physiology. Lopez writes of seeing two narwhals in Lancaster Sound in 1982, a startling place to see animals so rare. “The day I saw them I knew that no element of the earth’s history had ever brought me so far, so suddenly. It was as though something from a bestiary had taken shape, a creature strange as a giraffe. It was as if the testimony of someone I had no reason to doubt, yet could not quite believe, a story too farfetched, had been verified at a glance.” We ourselves saw no narwhals on our voyage, but anyone who has would have no reason to dismiss Olaus’s monsters so quickly.

Instead of narwhals, we saw plenty of its closest relative: the beluga, an animal in general far more social and visible. And while its name has none of the foreboding of its horned cousin, the beluga is a similar color as the narwhal, and the pods that swam by us bore the color of the bloated corpses of mariners, breaching the surface as they migrated by in the dozens. Who’s to say what Magnus Olaus would have seen in such a spectacle, and who’s to say to what degree he’d have been wrong?

“Between the printing of Olaus’s 1539 Carta Marina and the 1555 History,” Nigg writes, “modern zoology was being born, and with it the observation and classification of marine life.” As such, he argues, Olaus straddles two intellectual worlds, relying both on Pliny and other classical authorities, and on direct observation and personal testimony. “His commentaries on individual animals are a blend of scholarship, oral tradition, and personal experience — and are sometimes misguided, contradictory, and confusing.” As such, Olaus’s sea monsters, Nigg concludes, “clearly indicate the fluid nature of natural history.” This ability to capture such a fluidity, I would argue, is a thing to be celebrated. Reading his map strictly in terms of his accuracy as a cartographer is myopic; in addition to a map it is a natural history, as well as an anthology of folktales and myths — all told spatially rather than chronologically. A mixture of methodologies (sociology, geography, literature, history) synthesized into a single unified representation like a time-lapse photograph.

The perfect map — the map I wanted with me in the Arctic, one that was faithful to geography while still preserving the sense of wonder and mythology of a map like Olaus’s — is of course an impossibility. Borges wrote of the idea of a perfect map in his short story “On Exactitude in Science,” in which an empire’s cartographers conceive of a perfect map, one whose size is the same as the empire’s, and which conforms to it point for point. Perfect, but meaningless: “The following generations, who were not so fond of the study of cartography as their forebears had been, saw that that vast map was useless, and not without some pitilessness was it that they delivered it up to the inclemencies of sun and winters. In the deserts of the west, still today, there are tattered ruins of the map, inhabited by animals and beggars; in all the Land there is no other relic of the disciplines of cartography.” And that map, after all, was purely geographic — how much more difficult would it be to add layers of fantasy and the grotesque, of the evolution of human knowledge, all on the same plane?

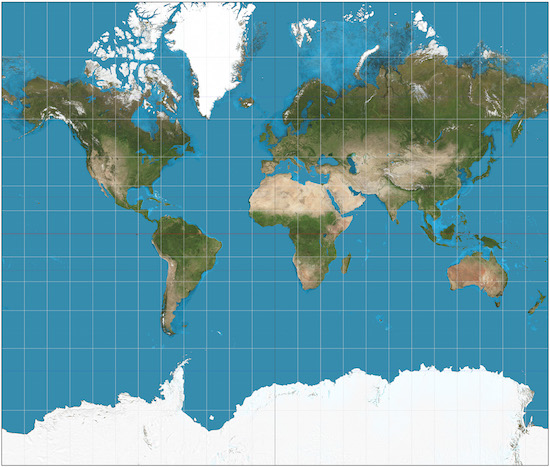

A map must begin by excluding things, rather than attempting to bring everything in. The map we are most accustomed to in the West is the Mercator Projection, often accused of not only being wrong, but also of perpetuating a European, Anglocentric bias. While the map is almost perfectly accurate at the equator, as it moves towards the poles it becomes increasingly distorted. With the Northern Atlantic at the center of the world, Africa appears smaller than Asia, the tip of Russia cutoff, and southern latitudes are blurred and downplayed altogether. But to be fair, the Mercator projection was not designed with any of this in mind — its primary function was to guide sailors from Europe to America and back; its full name is in fact Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendata: “New and Augmented Description of Earth Corrected for the Use of Sailors.” In this regard it is actually quite useful, even elegant: it represents lines of constant bearing, or “rhumb lines,” as straight lines, simplifying navigation immensely. To translate the world into such a useful order is not easy.

The danger lies in taking such a projection for reality. Any map will illuminate certain elements of the earth, while at the same time distorting, or erasing others altogether. The land is the raw material, unchanging, underneath these maps. You can lift one map up, lay another over the same plot of land, highlighting some new feature that didn’t exist before, while blotting out another. You can compare multiple maps and gradually attain a more synthetic picture, or you can rely on a single projection that misrepresents the actual world around you. What you cannot do, what Borges’ mapmakers tried to do, is to get everything onto one plane of paper.

Borges’ parable appears, among many places, in Allessandro Scafi’s Maps of Paradise, another work which offers a different way of reading maps. Scafi’s book follows cartographic attempts to place a physical paradise on the earth throughout the past two millennium, and how decisions about the location of such a place came to reflect our attitude towards time, space, and how we map them. Paradise — a word that may evolved from the ancient Medes term para-daiza, “a place enclosed with a clay wall,” and which the Greek writer Xenophon described as a hunting park for the elite — was for centuries an important and physical space to be placed on any serious map, a point to which the cities and towns of the world defined themselves in relation.

Medieval maps, for example, put Asia at the top of the map, with Europe and the Mediterranean, in far more detail, in the middle of the map, and Africa and the Atlantic crammed into the bottom. Giovanni Leardo’s 1442 map of the world, for example, is bisected between left and right along an axis that runs from the Indian Ocean at the top to the Sea of Spain at the bottom. To the left is Europe, or at least Southern Europe; everything above the Alps is crammed into a flat band of mountain and blank space. To the right North Africa, which gives way to a giant Red Sea, painted red. In Leardo’s map, Jerusalem is at the dead center of the world, and at the top of the map, in distant, unreachable Asia, is the Garden of Eden.

Medieval maps prioritized a physical Garden of Eden that was on the same plane of the rest of reality, though inaccessible. It was always located in Asia, far past mountains and rivers — theoretically possible, but practically unreachable. These mapmakers, Scafi notes, “did not deploy a universal system of map signs arranged in mathematical order, but depicted neighbouring places and events next to each other, without concern for the exact distance or direction between them. To them the crucial factor in the structure and content of mappae mundi was history, not geography.”

Like Olaus’s Carta Marina, these maps were not the result of shoddy cartography, but rather of a different set of priorities of seeing the world. “A medieval mappa mundi is far more than a spatial facsimile of the earth such as Google Earth,” Scafi writes. “[T]he incorporation of paradise on medieval world maps, far from being a naïve depiction of some picturesque fantasy land, epitomised a vital element of Christian doctrine. The Garden of Eden signified far more than a mythical state of innocence or fanciful dreamland, forever lost. The earthly paradise pointed to a present and future reality, that of Christian redemption.”

This general worldview changed only after the Protestant reformation. Luther argued that Paradise had disappeared from the earthly world after the Fall; accordingly, it began to disappear from maps in the sixteenth century onwards. Additionally, it was harder to contain both time and space on the same map; as cultures put more emphasis on commerce, and thus navigation, maps had less to do with the earthly paradise. East was no longer the top of the map, and maps began to assume the shape that we now take to be automatic: a purely functional description of the land with no regard to history, theology, or myth.

I wanted maps like these, maps that offered other ways of reading, other ways of experiencing the land, in part because up near the poles, traditional maps are so ill-suited, and distortion is most extreme. In Arctic Dreams Lopez writes of the maps he used in the Arctic Circle, how he traveled everywhere with them despite the fact that none of them were ever truly accurate. “They were the projection,” he writes, “of a wish that this space could be this well organized.”

The Arctic seems a place destined to be captured in incomplete and unreliable maps, even as the rest of the world is becoming increasingly overlaid with more and more maps — thanks to companies like Google and a world of endless collecting, mining, cataloging, aggregating and analyzing data. If Svalbard seems immune to this, it’s because up here the land is in a very specific sense useless, without much commercial or national value. When Svalbard was an active whaling and mining destination, there were attempts to map this land: charting locations of whales and seams of coal, but all that is mostly done now, and the value of this land is now mainly to tourists like myself, and scientists who engage with their own little maps.

But beyond the general disinterest in a perfect map of the region, the Arctic seems a place where the traditional rules of topography simply do not apply. Heading up the northwest coast of the archipelago, a horde of fulmars congregated one day in our wake. I had thought perhaps that the cook had thrown some scraps of food overboard, but I was told instead that when fulmars are hatched they follow the rivers to the ocean, and that these birds were now confusing our white wake in the ocean as another river, one they vainly tried to follow.

It’s not as though one can any longer do without GPS, sonar, and any other means at one’s disposal, particularly in open sea or trapped in dense fog, when a travelere of course becomes appreciative of finely detailed, stubbornly pragmatic maps — maps designed not for dreaming but for navigation. But as a mere passenger on that ship myself, I found myself longing for something like a bastard combination of Olaus’s map and a medieval mappa mundi, a map into which I could read more than just topography, but also history, culture, myth, the slow evolution of the natural world. A map that would contain not just actual rivers but all the false and temporary rivers like that of our boat’s wake, that the fulmars took to be as real as anything.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators