A Rogue By Compulsion (20)

By:

August 14, 2016

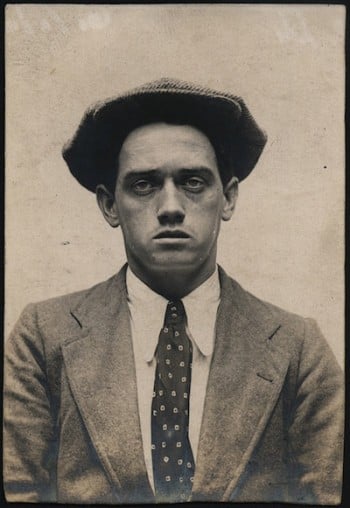

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

A Chinese proverb informs us that “there are three hundred and forty-six subjects for elegant conversation,” but during the trip down I think that Tommy and I confined ourselves almost exclusively to two. One was Mr. Bruce Latimer, and the other was Joyce’s amazing discovery about McMurtrie and Marks.

Concerning the latter Tommy was just as astonished and baffled as I was.

“I’m blessed if I know what to think about it, Neil,” he admitted. “If it was any one else but Joyce, I should say she’d made a mistake. What on earth could McMurtrie have had to do with that Jew beast?”

“Joyce seems to think he had quite a lot to do with him,” I said.

Tommy nodded. “I know. She’s made up her mind he did the job all right; but, hang it all, one doesn’t go and murder people without any conceivable reason.”

“I can conceive plenty of excellent reasons for murdering Marks,” I said impartially. “I should hardly think they would have appealed to McMurtrie, though. The chief thing that makes me suspicious about him is the fact of his knowing George and hiding it from me all this time. I suppose that was how he got hold of his information about the powder. George was almost the only person who knew of it.”

“I always thought the whole business was a devilish odd one,” growled Tommy; “but the more one finds out about it the queerer it seems to get. These people of yours — McMurtrie and Savaroff — are weird enough customers on their own, but when it comes to their being mixed up with both George and Marks…” he paused. “It will turn out next that Latimer’s in it too,” he added half-mockingly.

“I shouldn’t wonder,” I said. “I can’t swallow everything he told you, Tommy. It leaves too much unexplained. You see, I’m pretty certain that the chap who tried to do him in is one of McMurtrie’s crowd, and in that case —”

“In that case,” interrupted Tommy, with a short laugh, “we ought to have rather an interesting evening. Seems to me, Neil, we’re what you might call burning our boats this journey.”

The old compunction I had felt at first against dragging Tommy and Joyce into my affairs suddenly came back to me with renewed force.

“I’m a selfish brute, Thomas,” I said ruefully. “I think the best thing I could do really would be to drop overboard. The Lord knows what trouble I shall land you in before I’ve finished.”

“You’ll land me into the trouble of telling you not to talk rot in a minute,” he returned. Then, standing up and peering out ahead over the long dim expanse of water, dotted here and there with patches of blurred light, he added cheerfully: “You take her over now, Neil, We’re right at the end of the Yantlet, and after this morning you ought to know the rest of the way better than I do.”

He resigned the tiller to me, and pulling out his watch, held it up to the binnacle lamp.

“Close on a quarter to nine,” he said. “We shall just do it nicely if the engine doesn’t stop.”

“I hope so,” I said. “I should hate to keep a Government official waiting.”

We crossed the broad entrance into Queenborough Harbour, where the dim bulk of a couple of battleships loomed up vaguely through the haze. It was a strange, exhilarating sensation, throbbing along in the semi-darkness, with all sorts of unknown possibilities waiting for us ahead. More than ever I felt what Joyce had described in the morning — a sort of curious inward conviction that we were at last on the point of finding out the truth.

“We’d better slacken down a bit when we get near,” said Tommy. “Latimer specially told me to bring her in as quietly as I could.”

I nodded. “Right you are,” I said. “I wasn’t going to hurry, anyhow. It’s a tricky place, and I don’t want to smash up any more islands. One a day is quite enough.”

I slowed down the engine to about four knots an hour, and at this dignified pace we proceeded along the coast, keeping a watchful eye for the entrance to the creek. At last a vague outline of rising ground showed us that we were in the right neighbourhood, and bringing the Betty round, I headed her in very delicately towards the shore. It was distressingly dark, from a helmsman’s point of view, but Tommy, who had gone up into the bows, handed me back instructions, and by dint of infinite care we succeeded in making the opening with surprising accuracy.

The creek was quite small, with a steep bank one side perhaps fifteen feet high, and what looked like a stretch of mud or saltings on the other. Its natural beauties, however, if it had any, were rather obscured by the darkness.

“What shall we do now, Tommy?” I asked in a subdued voice. “Turn her round?”

He came back to the well. “Yes,” he said, “turn her round, and then I’ll cut out the engine and throttle her down. She’ll make a certain amount of row, but we can’t help that. I daren’t stop her; or she might never start again.”

We carried out our manoeuvre successfully, and then dropped over the anchor to keep us in position. I seated myself on the roof of the cabin, and pulling out a pipe, commenced to fill it.

“I wonder how long the interval is,” I said. “I suppose spying is a sort of job you can’t fix an exact time-limit to.”

Tommy looked at his watch again. “It’s just on a quarter to ten now. He told me not to wait after half-past.”

I stuffed down the baccy with my thumb, and felt in my pocket for a match.

“It seems to me —” I began.

The interesting remark I was about to make was never uttered. From the high ground away to the left came the sudden crack of a revolver shot that rang out with startling viciousness on the night air. It was followed almost instantly by a second.

Tommy and I leaped up together, inspired simultaneously by the same idea. Being half way there, however, I easily reached the painter first.

“All right,” I cried, “I’ll pick him up. You haul in and have her ready to start.”

I don’t know exactly what the record is for getting off in a dinghy in the dark, but I think I hold it with something to spare. I was away from the ship and sculling furiously for the shore in about the same time that it has taken to write this particular sentence.

I pulled straight for the direction in which I had heard the shots. It was the steepest part of the cliff, but under the circumstances it seemed the most likely spot at which my services would be required. People are apt to take a short cut when revolver bullets are chasing about the neighbourhood.

I stopped rowing a few yards from the shore, and swinging the boat round, stared up through the gloom. There was just light enough to make out the top of the cliff, which appeared to be covered by a thick growth of gorse several feet in height. I backed away a stroke or two, and as I did so, there came a sudden snapping, rustling sound from up above, and the next instant the figure of a man broke through the bushes.

He peered down eagerly at the water.

“That you, Morrison?” he called out in a low, distinct voice, which I recognized at once.

“Yes,” I answered briefly. It struck me as being no time for elaborate explanations.

Mr. Latimer was evidently of the same opinion. Without any further remark, he stepped forward to the edge of the cliff, and jumping well out into the air, came down with a beautiful splash about a dozen yards from the boat.

He rose to the surface at once, and I was alongside of him a moment later.

“It’s all right,” I said, as he clutched hold of the stern. “Morrison’s in the Betty; I’m lending him a hand.”

I caught his arm to help him in, and as I did so he gave a little sharp exclamation of pain.

“Hullo!” I said, shifting my grip. “What’s the matter?”

With an effort he hoisted himself up into the boat.

“Nothing much, thanks,” he answered in that curious composed voice of his. “I think one of our friends made a luckier shot than he deserved to. It’s only my left arm, though.”

I seized the sculls, and began to pull off quickly for the Betty.

“We’ll look at it in a second,” I said. “Are they after you?”

He laughed. “Yes, some little way after. I took the precaution of starting in the other direction and then doubling back. It worked excellently.”

He spoke in the same rather amused drawl as he had done at the hut, and there was no hint of hurry or excitement in his manner. I could just see, however, that he was dressed in rough, common-looking clothes, and that he was no longer wearing an eye-glass. If he had had a cap, he had evidently parted with it during his dive into the sea.

A few strokes brought us to the Betty, where Tommy was leaning over the side ready to receive us.

“All right?” he inquired coolly, as we scrambled on board.

“Nothing serious,” replied Latimer. “Thanks to you and — and this gentleman.”

“They’ve winged him, Tommy,” I said. “Can you take her out while I have a squint at the damage?”

Tommy’s answer was to thrust in the clutch of the engine, and with an abrupt jerk we started off down the creek. As we did so there came a sudden hail from the shore.

“Boat ahoy! What boat’s that?”

It was a deep, rather dictatorial sort of voice, with the faintest possible touch of a foreign accent about it.

Latimer replied at once in a cheerful, good-natured bawl, amazingly different from his ordinary tone:

“Private launch, Vanity, Southend; and who the hell are you?”

Whether the vigour of the reply upset our questioner or not, I can’t say. Anyhow he returned no answer, and leaving him to think what he pleased, we continued our way out into the main stream.

“Come into the cabin and let’s have a look at you,” I said to Latimer. “You must get those wet things off, anyhow.”

He followed me inside, where I took down the small hanging lamp and placed it on the table. Then very carefully I helped him strip off his coat, bringing to light a grey flannel shirt, the left sleeve of which was soaked in blood.

I took out my knife, and ripped it up from the cuff to the shoulder. The wound was about a couple of inches above the elbow, a small clean puncture right through from side to side. It was bleeding a bit, but one could see at a glance that the bullet had just missed the bone.

“You’re lucky,” I said. “Another quarter of an inch, and that arm would have been precious little use to you for the next two months. Does it hurt much?”

He shook his head. “Not the least,” he replied carelessly. “I hardly knew I was hit until you grabbed hold of me.”

I tied my handkerchief round as tightly as possible just above the place, and then going to the locker hauled out our spare fancy costume which had previously done duty for Mr. Gow.

“You get these on first,” I said, “and then I’ll fix you up properly.”

I thrust my head out through the cabin door to see how things were going, and found that we were already clear of the creek and heading back towards Queenborough. Tommy, who was sitting at the tiller puffing away peacefully at a pipe, removed the latter article from his mouth.

“Where are we going to, my pretty maid?” he inquired.

“I don’t know,” I said; “I’ll ask the passenger as soon as I’ve finished doctoring him.”

I returned to the cabin, where Mr. Latimer, who had stripped off his wet garments, was attempting to dry himself with a dishcloth. I managed to find him a towel, and then, as soon as he had struggled into a pair of flannel trousers and a vest, I set about the job of tying up his arm. An old shirt of Tommy’s served me as a bandage, and although I don’t profess to be an expert, I knew enough about first aid to make a fairly serviceable job of it. Anyhow Mr. Latimer expressed himself as being completely satisfied.

“You’d better have a drink now,” I said. “That’s part of the treatment.”

I mixed him a stiff peg, which he consumed without protest; and then, after he had inserted himself carefully into a jersey and coat, we both went outside.

“Hullo!” exclaimed Tommy genially. “How do you feel now?”

Our visitor sat down on one of the side seats in the cockpit, and contemplated us both with his pleasant smile.

“I feel extremely obliged to you, Morrison,” he said. “You have a way of keeping your engagements that I find most satisfactory.”

Tommy laughed. “I had a bit of luck,” he returned. “If I hadn’t picked up our pal here I doubt if I should have got down in time after all. By the way, there’s no need to introduce you. You’ve met each other before at the hut, haven’t you?”

Latimer, who was just lighting a cigar which I had offered him, paused for a moment in the operation.

“Yes,” he said quietly. “We have met each other before. But I should rather like to be introduced, all the same.”

Something in his manner struck me as being a trifle odd, but if Tommy noticed it he certainly didn’t betray the fact.

“Well, you shall be,” he answered cheerfully. “This is Mr. James Nicholson.”

Latimer finished lighting his cigar, blew out the match, and dropped it carefully over the side.

“Indeed,” he said. “It only shows how extremely inaccurate one’s reasoning powers can be.”

There was a short but rather pregnant pause. Then Tommy leaned forward.

“What do you mean?” he asked, in that peculiarly gentle voice which he keeps for the most unhealthy occasions.

Latimer’s face remained beautifully impassive. “I was under the mistaken impression,” he answered slowly, “that I owed my life to Mr. Neil Lyndon.”

For perhaps three seconds none of us spoke; then I broke the silence with a short laugh.

“We are up against it, Thomas,” I observed.

Tommy looked backwards and forwards from one to the other of us.

“What shall we do?” he said quietly. “Throw him in the river?”

“It would be rather extravagant,” I objected, “after we’ve just pulled him out.”

Latimer smiled. “I am not sure I don’t deserve it. I have lied to you, Morrison, all through in the most disgraceful manner.” Then he paused.”Still it would be extravagant,” he added. “I think I can convince you of that before we get to Queenborough.”

Tommy throttled down the engine to about its lowest running point.

“Look here, Latimer,” he said. “We’re not going to Queenborough, or anywhere else, until we’ve got the truth out of you. You understand that, of course. You’ve put yourself in our power deliberately, and you must have some reason. One doesn’t cut one’s throat for fun.”

He spoke in his usual pleasant fashion, but there was a grim seriousness behind it which no one could pretend to misunderstand. Latimer, at all events, made no attempt to. He merely nodded his head approvingly.

“You’re quite right,” he said. “I had made up my mind you should hear some of the truth tonight in any case; that was the chief reason why I asked you to come and pick me up. When I saw you had brought Mr. Lyndon with you, I determined to tell you everything. It’s the simplest and best way, after all.”

He stopped for a moment, and we all three sat there in silence, while the Betty slowly throbbed her way forward, splashing off the black water from either bow. Then Latimer began to speak again quite quietly.

“I am in the Secret Service,” he said; “but you can forget the rest of what I told you the other night, Morrison. I am after bigger game than a couple of German spies — though they come into it right enough. I am on the track of three friends of Mr. Lyndon’s, who just now are as badly wanted in Whitehall as they probably are in hell.”

I leaned back with a certain curious thrill of satisfaction.

“I thought so,” I said softly.

He glanced at me with his keen blue eyes, and the light of the lamp shining on his face showed up its square dogged lines of strength and purpose. It was a fine face — the face of a man without weakness and without fear.

“It’s nearly twelve months ago now,” he continued, “that we first began to realize at headquarters that there was something queer going on. There’s always a certain amount of spying in every country — the sort of quiet, semi-official kind that doesn’t do any one a ha’porth of practical harm. Now and then, of course, somebody gets dropped on, and there’s a fuss in the papers, but nobody really bothers much about it. This was different, however. Two or three times things happened that did matter very much indeed. They were the sort of things that showed us pretty plainly we were up against something entirely new — some kind of organized affair that had nothing on earth to do with the usual casual spying.

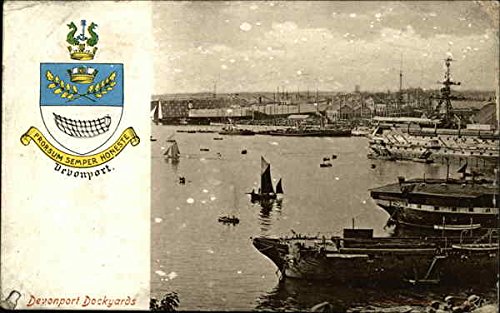

“Well, I made up my mind to get to the bottom of it. Casement, who is nominally the head of our department, gave me an absolutely free hand, and I set to work in my own way quite independently of the police. It was six months before I got hold of a clue. Then some designs — some valuable battleship designs — disappeared from Devonport Dockyard. It was a queer case, but there were one or two things about it which made me pretty sure it was the work of the same gang, and that for the time, at all events, they were somewhere in the neighbourhood.

“I needn’t bother you now with all the details of how I actually ran them to earth. It wasn’t an easy job. They weren’t the sort of people who left any spare bits of evidence lying around, and by the time I found out where they were living it was just too late.” He turned to me. “Otherwise, Mr. Lyndon, I think we might possibly have had the pleasure of meeting earlier.”

A sudden forgotten recollection of my first interview with McMurtrie flashed vividly into my mind.

“By Jove!” I exclaimed. “What a fool I am! I knew I’d heard your name somewhere before.”

Latimer nodded. “Yes,” he said. “I daresay I had begun to arouse a certain amount of interest in the household by the time you arrived.” He paused. “By the way, I am still quite in the dark as to how you actually got in with them. Had they managed to send you a message into the prison?”

“No,” I said. “I’m equally in the dark as to how you’ve found out who I am, but you seem to know so much already, you may as well have the truth. It was chance; just pure chance and a bicycle. I hadn’t the remotest notion who lived in the house. I was trying to steal some food.”

Latimer nodded again. “It was a chance that a man like McMurtrie wasn’t likely to waste. I don’t know yet how you’re paying him for his help, but I should imagine it’s a fairly stiff price. However, we’ll come back to that afterwards.

“I was just too late, as I told you, to interrupt your pleasant little house-party. I managed to find out, however, that some of you had gone to London, and I followed at once. It was then, I think, that the doctor decided it was time to take the gloves off.

“So far, although I’d been on their heels for weeks, I hadn’t set eyes on any of the gang personally. All the same, I had a pretty good idea of what McMurtrie and Savaroff were like to look at, and I fancy they probably guessed as much. Anyhow, as you know, it was the third member of the brotherhood — a gentleman who, I believe, calls himself Hoffman — who was entrusted with the job of putting me out of the way.”

A faint mocking smile flickered for a moment round his lips.

“That was where the doctor made his first slip. It never pays to underestimate your enemy. Hoffman certainly had a good story, and he told it well, but after thirteen years in the Secret Service I shouldn’t trust the Archbishop of Canterbury till I’d proved his credentials. I agreed to dine at Parelli’s, but I took the precaution of having two of my own men there as well — one in the restaurant and one outside in the street. I had given them instructions that, whatever happened, they were to keep Hoffman shadowed till further orders.

“Well, you know how things turned out almost as well as I do. I was vastly obliged to you for sending me that note, but as a matter of fact I hadn’t the least intention of drinking the wine. Indeed, I turned away purposely to give Hoffman the chance to doctor it. What did beat me altogether was who you were. I naturally couldn’t place you at all. I saw that you recognized one of us when you came in, and that you were watching our table pretty attentively in the glass. I had a horrible suspicion for a moment that you were a Scotland Yard man, and were going to bungle the whole business by arresting Hoffman. That was why I sent you my card; I knew if you were at the Yard you’d recognize my name.”

“I severed my connection with the police some time ago,” I said drily. “What happened after dinner? I’ve been longing to know ever since.”

“I got rid of Hoffman at the door, and from the time he left the restaurant my men never lost him again. They shadowed him to his lodgings — he was living in a side street near Victoria — and for the next two days I got a detailed report of everything he did. It was quite interesting reading. Amongst other things it included paying a morning visit to the hut you’re living in at present, Mr. Lyndon, and going on from there to spend the afternoon calling on some friends at Sheppey.”

I laughed gently, and turned to Tommy. “Amazingly simple,” I said, “when you know how it’s done.”

Tommy nodded. “I’ve got all that part, but I’m still utterly at sea about how he dropped on to you.”

“That was simpler still,” answered Latimer. “One of my men told me that the hut was empty for the time, so I came down to have a look at it.” He turned to me. “Of course I recognized you at once as the obliging stranger of the restaurant. That didn’t put me much farther on the road, but when Morrison rolled up with his delightfully ingenious yarn, he gave me just the clue I was looking for. I knew his story was all a lie because I’d seen you since. Well, a man like Morrison doesn’t butt into this sort of business without a particularly good reason, and it didn’t take me very long to guess what his reason was. You see I remembered him chiefly in connection with your trial. I knew he was your greatest friend; I knew you had escaped from Dartmoor and disappeared somewhere in the neighbourhood of McMurtrie’s place, and putting two and two together there was only one conclusion I could possibly come to.”

“My appearance must have taken a little getting over,” I suggested.

Latimer shrugged his shoulders. “Apart from your features you exactly fitted the bill, and I had learned enough about McMurtrie’s past performances not to let that worry me. What I couldn’t make out was why he should have run the risk of helping you. Of course you might have offered him a large sum of money — if you had it put away somewhere — but in that case there seemed no reason why you should be hanging about in a hut on the Thames marshes.”

“Why didn’t you tell the police?” asked Tommy.

“The police!” Latimer’s voice was full of pleasant irony. “My dear Morrison, we don’t drag the police into this sort of business; our great object is to keep them out of it. Mr. Lyndon’s affairs had nothing to do with me officially apart from his being mixed up with McMurtrie. Besides, my private sympathies were entirely with him. Not only had he tried to save my life at Parelli’s, but ever since the trial I have always been under the impression he was fully entitled to slaughter Mr. — Mr. — whatever the scoundrel’s name was.”

I acknowledged the remark with a slight bow. “Thank you,” I said. “As a matter of sober fact I didn’t kill him, but I shouldn’t be the least sorry for it if I had.”

Latimer looked at me for a moment straight in the eyes.

“We’ve treated you beautifully as a nation,” he said slowly. “It’s an impertinence on my part to expect you to help us.”

I laughed. “Go on,” I said. “Let’s get it straightened out anyhow.”

“Well, the straightening out must be largely done by you. As far as I’m concerned the rest of the story can be told very quickly. For various reasons I got to the conclusion that in some way or other the two gentlemen on Sheppey had a good deal to do with the matter. My men had been making a few inquiries about them, and from what we’d learned I was strongly inclined to think they were a couple of German naval officers over here on leave. If that was so, the fact that they were in communication with Hoffman made it pretty plain where McMurtrie was finding his market. My men had told me they were generally away on the mainland in the evening, and I made up my mind I’d have a look at the place the first chance I got. I asked Morrison to come down and pick me up in his boat for two reasons — partly because I wanted to keep in touch with you both, and partly because I thought it might come in handy to have a second line of retreat.”

“It was rather convenient, as things turned out,” interposed Tommy.

“Very,” admitted Latimer drily. “They got back to the garden just as I had opened one of the windows, and shot at me from behind the hedge. If it hadn’t been for the light they must have picked me off.”

He stopped, and standing up in the well, looked round. By this time we were again just off the entrance to Queenborough, and the thick haze that had obscured everything earlier in the evening was rapidly thinning away. A watery moon showed up the various warships at anchor—dim grey formless shapes, marked by blurred lights.

“What do you say?” he asked, turning to Tommy. “Shall we run in here and pick up some moorings? Before we go any further I want to hear Lyndon’s part of the story, and then we all three shall know exactly where we are. After that you can throw me in the sea, or — or — well, I think there are several possible alternatives.”

“We’ll find out anyhow,” said Tommy.

He turned the Betty towards the shore, and we worked our way carefully into the harbour. We ran on past the anchored vessels, until we were right opposite the Queenborough jetty, where we discovered some unoccupied moorings which we promptly adopted. It was a snug berth, and a fairly isolated one — a rakish-looking little gunboat being our nearest neighbour.

In this pleasant atmosphere of law and order I proceeded to narrate as briefly and quickly as possible the main facts about my escape and its results. I felt that we had gone too far now to keep anything back. Latimer had boldly placed his own cards face upwards on the table, and short of sending him to the fishes, there seemed to be nothing else to do except to follow his example. As he himself had said, we should then at least know exactly how we stood with regard to each other.

He listened to me for the most part in silence, but the few interruptions that he did make showed the almost fierce attention with which he was following my story. I don’t think his eyes ever left my face from the first word to the last.

When I had finished he sat on for perhaps a minute without speaking. Then very deliberately he leaned across and held out his hand. We exchanged grips, and for once in my life I found a man whose fingers seemed as strong as my own.

“I don’t know whether that makes you an accessory after the fact,” I said. “I believe it’s about eighteen months for being civil to an escaped convict.”

He let go my hand, and getting up from his seat leaned back against the door of the cabin facing us both.

“You may be an escaped convict, Mr. Lyndon,” he said slowly, “but if you choose I believe you can do more for England than any man alive.”

There was a short pause.

“It seems to me,” interrupted Tommy, “that England is a little bit in Neil’s debt already.”

“That doesn’t matter,” I observed generously. “Let’s hear what Mr. Latimer has got to say.” I turned to him. “Who are McMurtrie and Savaroff?” I asked, “and what the devil’s the meaning of it all?”

“The meaning is plain enough to a certain point,” he answered. “I haven’t the least doubt that they intend to sell the secret of your powder to Germany, just as they’ve sold their other information. If I knew for certain it was only that, I should act, and act at once.”

He stopped.

“Well?” I said.

“I believe there’s something more behind it — something we’ve got to find out before we strike. For the last two months Germany has taken a tone towards us diplomatically that can only have one explanation. They mean to get their way or fight, and if it comes to a fight they’re under the impression they’re going to beat us.”

“And you really believe McMurtrie and Savaroff are responsible for their optimism?” I asked a little incredulously.

Latimer nodded. “Dr. McMurtrie,” he said in his quiet drawl, “is the most dangerous man in Europe. He is partly English and partly Russian by birth. At one time he used to be court physician at St. Petersburg. Savaroff is a German Pole — his real name is Vassiloff. Between them they were largely responsible for the early disasters in the Japanese war.”

For a moment no one spoke. Then Tommy leaned forward. “I say, Latimer,” he exclaimed, “is this serious history?”

“The Russian Government,” replied Latimer, “are most certainly under that impression.”

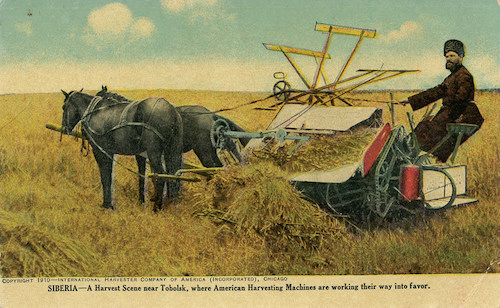

“But if they know about it,” I objected, “how is it that McMurtrie and Savaroff aren’t in Siberia? I’ve never heard that the Russians are particularly tender-hearted where traitors are concerned.”

Latimer indulged in that peculiarly dry smile of his. “If the Government had got hold of them I think their destination would have been a much warmer one than Siberia. As it was they disappeared just in time. There was a gang of them — four or five at the least — and all men of position and influence. They must have made an enormous amount of money out of the Japs. In the end one of them rounded on the others — at least that’s what appears to have happened. Anyhow McMurtrie and Savaroff skipped, and skipped in such a hurry that they seem to have left most of their savings behind them. I suppose that’s what made them start business again in England.”

“You’re absolutely sure they’re the same pair?” asked Tommy.

“Absolutely. I’ve got their full description from the Russian police. It tallies in every way — even to Savaroff’s daughter. There is a girl with them, I believe?”

“Yes,” I said. “There’s a girl.” Then I paused for a moment. “Look here, Latimer,” I went on. “What is it you want me to do? I’ll help you in any way I can. When I made my bargain with McMurtrie I hadn’t a notion what his real game was. I don’t in the least want to buy my freedom by selling England to Germany. The only thing I flatly and utterly refuse to do is to serve out the rest of my sentence. If it’s bound to come out who I am, you must give me your word I shall have a reasonable warning. I don’t much mind dying — especially if I can arrange for ten minutes with George first — but quite candidly I’d see England wiped off the map before I’d go back to Dartmoor.”

Latimer made a slight gesture with his hands. “You’ve saved my life, once at all events,” he said. “It may seem a trifle to you, but it’s a matter of quite considerable importance to me. I don’t think you need worry about going back to Dartmoor — not as long as the Secret Service is in existence.”

“Well, what is it you want me to do?” I asked again.

He was silent for a moment or two, as though arranging his ideas. Then he began to speak very slowly and deliberately.

“I want you to go on as if nothing had happened. Write to McMurtrie the first thing tomorrow morning and tell him that you’ve made the powder. He is sure to come down to the hut at once. You can show him that it’s genuine, but on no account let him have any of it to take away. Tell him that you will only hand over the secret on receipt of a written agreement, and make him see that you’re absolutely serious. Meanwhile let me know everything that happens as soon as you possibly can. Telegraph to me at 145 Jermyn Street. You can send in the messages to Tilbury by the man who’s looking after your boat. Use some quick simple cypher — suppose we say the alphabet backwards, Z for A and so on. Have you got plenty of money?”

I nodded. “I should like to have some sort of notion what you’re going to do,” I said. “It would be much more inspiriting than working in the dark.”

“It depends entirely on the next two days. I shall go back to London tonight and find out if either of my men has got hold of any fresh information. Then I shall put the whole thing in front of Casement. If he agrees with me I shall wait till the last possible moment before striking. We’ve enough evidence about the Devonport case to arrest McMurtrie and Savaroff straight away, but I feel it would be madness while there’s a chance of getting to the bottom of this business. Perhaps you understand now why I’ve risked everything tonight. We’re playing for high stakes, Mr. Lyndon, and you —” he paused — “well, I’m inclined to think that you’ve the ace of trumps.”

I stood up and faced him. “I hope so,” I said. “I’m rather tired of being taken for the Knave.”

“Isn’t there a job for me?” asked Tommy pathetically. “I’m open for anything, especially if it wants a bit of physical violence.”

“There will probably be a demand for that a little later on,” said Latimer in his quiet drawl. “At present I want you to come back with me to London. I shall find plenty for you to do there, Morrison. The fewer people that are mixed up in this affair the better.” He turned to me. “You can take the boat back to Tilbury alone if we go ashore here?”

I nodded, and he once more held out his hand.

“We shall meet again soon,” he said — “very soon I think. Have you ever read Longfellow?”

It was such a surprising question that I couldn’t help smiling.

“Not recently,” I said. “I haven’t been in the mood for poetry the last two or three years.”

He held my hand and his blue eyes looked steadily into mine.

“Ah,” he said. “I don’t want to be too optimistic, but there’s a verse in Longfellow which I think you might like.” He paused again. “It has something to do with the Mills of God,” he added slowly. *

* Though the mills of God grind slowly,

Yet they grind exceeding small;

Though with patience he stands waiting,

With exactness grinds he all.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.