A Rogue By Compulsion (19)

By:

August 9, 2016

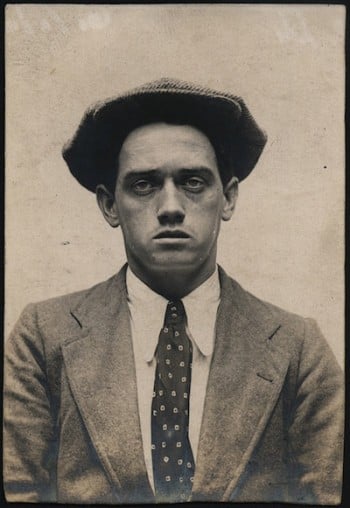

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

The eastern sky was just flushing into light when I got back to the creek at four o’clock. It was a beautiful morning — cool and still — with the sweet freshness of early dawn in the air, and the promise of a long unclouded day of spring sunshine.

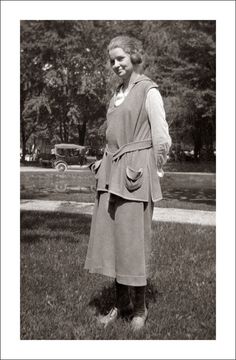

I tugged the dinghy down to the water, and pushed off for the Betty, which looked strangely small and unreal lying there in the dim, mysterious twilight. The sound I made as I drew near must have reached Joyce’s ears. She was up on deck in a moment, fully dressed, and with her hair twisted into a long bronze plait that hung down some way below her waist. She looked as fresh and fair as the dawn itself.

“Beautifully punctual,” she called out over the side. “I knew you would be, so I started getting breakfast.”

I caught hold of the gunwale and scrambled on board.

“It’s like living at the Savoy,” I said. “Breakfast was a luxury that had never entered my head.”

“Well, it’s going to now,” she returned, “unless you’re in too great a hurry to start. It’s all ready in the cabin.”

“We can spare ten minutes certainly,” I said. “Experiments should always be made on a full body.”

I tied up the dinghy and followed her inside, where the table was decorated with bread and butter and the remnants of the cold pheasant, while a kettle hissed away cheerfully on the Primus.

“I don’t believe you’ve been to bed at all, Joyce,” I said. “And yet you look as if you’d just slipped out of Paradise by accident.”

She laughed, and putting her hand in my side-pocket, took out my handkerchief to lift off the kettle with.

“I didn’t want to sleep,” she said. “I was too happy, and too miserable. It’s the widest-awake mixture I ever tried.” Then, picking up the teapot, she added curiously: “Where’s the powder? I expected to see you arrive with a large keg over your shoulder.”

I sat down at the table and produced a couple of glass flasks, tightly corked.

“Here you are,” I said. “This is ordinary gunpowder, and this other one’s my stuff. It looks harmless enough, doesn’t it?”

Joyce took both flasks and examined them with interest. “You’ve not brought very much of it,” she said. “I was hoping we were going to have a really big blow-up.”

“It will be big enough,” I returned consolingly, “unless I’ve made a mistake.”

“Where are you going to do it?” she asked.

“Somewhere at the back of Canvey Island,” I said. “There’s no one to wake up there except the sea-gulls, and we can be out of sight round the corner before it explodes. I’ve got about twenty feet of fuse, which will give us at least a quarter of an hour to get away in.”

“What fun!” exclaimed Joyce. “I feel just like an anarchist or something; and it’s lovely to know that one’s launching a new invention. We ought to have kept that bottle of champagne to christen it with.”

“Yes,” I said regretfully; “it was the real christening brand too.”

There was a short silence. “I’ve thought of a name for it,” cried Joyce suddenly. “The powder, I mean. We’ll call it Lyndonite. It sounds like something that goes off with a bang, doesn’t it?”

I laughed. “It would probably suggest that to the prison authorities,” I said. “Anyhow, Lyndonite it shall be.”

We finished breakfast, and going up on deck I proceeded to haul in the anchor, while Joyce stowed away the crockery and provisions below. For once in a way the engine started without much difficulty, and as the tide was running out fast it didn’t take us very long to reach the mouth of the creek.

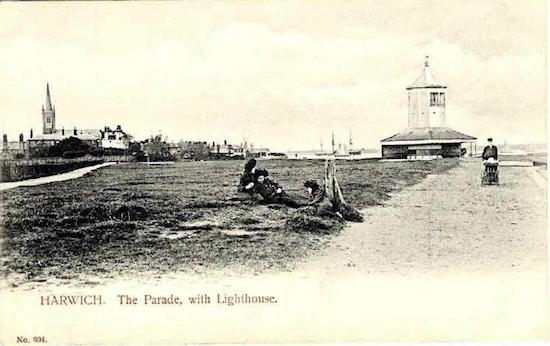

Once outside, I set a course down stream as close to the northern shore as I dared go. Except for a rusty-looking steam tramp we had the whole river to ourselves, not even a solitary barge breaking the long stretch of grey water. One by one the old landmarks — Mucking Lighthouse, the Thames Cattle Wharf, and Hole Haven — were left behind, and at last the entrance to the creek that runs round behind Canvey Island came into sight.

One would never accuse it of being a cheerful, bustling sort of place at the best of times, but at five o’clock in the morning it seemed the very picture of uninhabited desolation. A better locality in which to enjoy a little quiet practice with new explosives it would be difficult to imagine.

I navigated the Betty in rather gingerly, for it was over three years since I had visited the spot. Joyce kept on sounding diligently with the lead either side of the boat, and at last we brought up in about one and a half fathom, just comfortably out of sight of the main stream.

“This will do nicely,” I said. “We’ll turn her round first, and then I’ll row into the bank and fix things up under that tree over there. We can be back in the river before anything happens.”

“Can’t we stop and watch?” asked Joyce. “I should love to see it go off.”

I shook my head. “Unless I’ve made a mistake,” I said, “it will be much healthier round the corner. We’ll come back and see what’s happened afterwards.”

By the aid of some delicate manoeuvring I brought the Betty round, and then getting into the dinghy pulled myself ashore.

It was quite unnecessary for my experiment to make any complicated preparations. All I had to do was to dig a hole in the bank with a trowel that I had brought for the purpose, empty my stuff into that, and tip in the gunpowder on top. When I had finished I covered the whole thing over with earth, leaving a clear passage for the fuse, and then lighting the end of the latter, jumped back into the boat and pulled off rapidly for the Betty.

We didn’t waste any time dawdling about. Joyce seized the painter as I climbed on board, and hurrying to the tiller I started off down the creek as fast as we could go, taking very particular pains not to run aground.

We had reached the mouth, and I was swinging her round into the main river, when a sudden rumbling roar disturbed the peacefulness of the dawn. Joyce, who was staring out over the stern, gave a little startled cry, and glancing hastily back I was just in time to see a disintegrated-looking tree soaring gaily up into the air in the midst of a huge column of dust and smoke. The next moment a rain of falling fragments of earth and wood came splashing down into the water — a few stray pieces actually reaching the Betty, which rocked vigorously as a minature tidal wave swept after us up the creek.

I put down my helm and brought her round so as to face the stricken field.

“We seem to have done it, Joyce,” I observed with some contentment.

She gave a little gasping sort of laugh. “It was splendid!” she said. “But, oh, Neil, what appalling stuff it must be! It’s blown up half Canvey Island!”

“Never mind,” I said cheerfully. “There are plenty of other islands left. Let’s get into the dinghy and see what the damage really amounts to. I fancy it’s fairly useful.”

We anchored the Betty, and then pulled up the creek towards the scene of the explosion, where a gaping aperture in the bank was plainly visible. As we drew near I saw that it extended, roughly speaking, in a half-circle of perhaps twenty yards diameter. The whole of this, which had previously been a solid bank of grass and earth, was now nothing but a muddy pool. Of the unfortunate tree which had marked the site there was not a vestige remaining.

I regarded it all from the boat with the complacent pride of a successful inventor. “It’s even better than I expected, Joyce,” I said. “If one can do this with three-quarters of a pound, just fancy the effect of a couple of hundredweight. It would shift half London.”

Joyce nodded. “They’ll be more anxious than ever to get hold of it, when they know,” she said. “What are you going to do? Write and tell McMurtrie that you’ve succeeded?”

“I haven’t quite decided,” I answered. “I shall wait till tomorrow or the next day, anyhow. I want to hear what Sonia has got to say first.” Then, backing away the boat, I added: “We’d better get out of this as soon as we can. It’s just possible some one may have heard the explosion and come pushing along to find out what’s the matter. People are so horribly inquisitive.”

Joyce laughed. “It would be rather awkward, wouldn’t it? We couldn’t very well say it was an earthquake. It looks too neat and tidy.”

Fortunately for us, if there was any one in the neighbourhood who had heard the noise, they were either too lazy or too incurious to investigate the cause. We got back on board the Betty and took her out into the main stream without seeing a sign of any one except ourselves. The hull of the steam tramp was just visible in the far distance, but except for that the river was still pleasantly deserted.

“What shall we do now, Joyce?” I asked. “It seems to me that this is an occasion which distinctly requires celebrating.”

Joyce thought for a moment. “Let’s go for a long sail,” she suggested, “and then put in at Southend and have asparagus for lunch.”

I looked at her with affectionate approval. “You always have beautiful ideas,” I said. Then a sudden inspiration seized me. “I’ve got it!” I cried. “What do you say to running down to Sheppey and paying a call on our German pals?”

Joyce’s blue eyes sparkled. “It would be lovely,” she said, with a deep breath; “but dare we risk it?”

“There’s no risk,” I rejoined. “When I said ‘pay a call,’ I didn’t mean it quite literally. My idea was to cruise along the coast and just find out exactly where their precious bungalow is, and what they do with that launch of theirs when they’re not swamping inquisitive boatmen. It’s the sort of information that might turn out useful.”

Joyce nodded. “We’ll go,” she said briefly. “What about the tide?”

“Oh, the tide doesn’t matter,” I replied. “It will be dead out by the time we get to Southend; but we only draw about three foot six, and we can cut across through the Jenkin Swatch. There’s water enough off Sheppey to float a battleship.”

It was the work of a few minutes to pull in the anchor and haul up the sails, which filled immediately to a slight breeze that had just sprung up from the west. Leaving a still peaceful, if somewhat mutilated, Canvey Island behind us, we started off down the river, gliding along with an agreeable smoothness that fitted in very nicely with my state of mind.

Indeed I don’t think I had ever felt anything so nearly approaching complete serenity since my escape from Dartmoor. It is true that the tangle in which I was involved, appeared more threatening and complicated than ever, but one gets so used to sitting on a powder mine that the situation was gradually ceasing to distress me.

At all events I had made my explosive, and that was one great step towards a solution of some sort. If McMurtrie was prepared to play the game with me I should in a few days be in what the newspapers call “a position of comparative affluence,” while if his intentions were less straightforward I should at least have some definite idea as to where I was. Sonia’s promised disclosures were a guarantee of that.

But apart from these considerations the mere fact of having Joyce sitting beside me in the boat while we bowled along cheerfully through the water was quite enough in itself to account for my new-found happiness. One realizes some things in life with curious abruptness, and I knew now how deeply and passionately I loved her. I suppose I had always done so really, but she had been little more than a child in the old Chelsea days, and the sort of brotherly tenderness and pride I had had for her must have blinded me to the truth.

Anyhow it was out now; out beyond any question of doubt or argument. She was as necessary and dear to me as the stars are to the night, and it seemed ridiculously impossible to contemplate any sort of existence without her. Not that I wasted much energy attempting the feat; the present was sufficiently charming to occupy my entire time.

We passed Leigh and Southend, the former with its fleet of fishing-smacks and the latter with its long unlovely pier, and then nosed our way delicately into the Jenkin Swatch, that convenient ditch which runs right across the mouth of the Thames. The sun was now high in the sky, and one could see signs of activity on the various barges that were hanging about the neighbourhood waiting for the tide.

I pointed away past the Nore Lightship towards a bit of rising ground on the low-lying Sheppey coast.

“That’s about where our pals are hanging out,” I said. “There’s a little deep-water creek there, which Tommy and I used to use sometimes, and according to Mr. Gow their bungalow is close by.”

Joyce peered out under her hand across the intervening water. “It’s a nice situation,” she observed, “for artists.”

I laughed. “Yes,” I said. “They are so close to Sheerness and Shoeburyness, and other places of beauty. I expect they’ve done quite a lot of quiet sketching.”

We reached the end of the Swatch, and leaving Queenborough, with its grim collection of battleships and coal hulks, to starboard, we stood out to sea along the coastline. It was a fairly long sail to the place which I had pointed out to Joyce, but with a light breeze behind her the Betty danced along so gaily that we covered the distance in a surprisingly short time.

As we drew near, Joyce got out Tommy’s field-glasses from the cabin, and kneeling up on the seat in the well, focused them carefully on the spot.

“There’s the entrance to the creek all right,” she said, “but I don’t see any sign of a bungalow anywhere.” She moved the glasses slowly from side to side. “Oh, yes,” she exclaimed suddenly, “I’ve got it now — right up on the cliff there, away to the left. One can only just see the roof, though, and it seems some way from the creek.”

She resigned the glasses to me, and took over the tiller, while I had a turn at examining the coast.

I soon made out the roof of the bungalow, which, as Joyce had said, was the only part visible. It stood in a very lonely position, high up on a piece of rising ground, and half hidden from the sea by what seemed like a thick privet hedge. To judge by the smoke which I could just discern rising from its solitary chimney, it looked as if the occupants were addicted to the excellent habit of early rising.

There was no other sign of them to be seen, however, and if the launch was lying anywhere about, it was at all events invisible from the sea. I refreshed my memory with a long, careful scrutiny of the entrance to the creek, and then handing the glasses back to Joyce I again assumed control of the boat.

“Well,” I observed, “we haven’t wasted the morning. We know where their bungalow door is, anyway.”

Joyce nodded. “It may come in very handy,” she said, “in case you ever want to pay them a surprise call.”

Exactly how soon that contingency was going to occur we neither of us guessed or imagined!

We reached the Nore Lightship, and waving a courteous greeting to a patient-looking gentleman who was spitting over the side, commenced our long beat back in the direction of Southend. It was slow work, for the tide was only just beginning to turn, and the wind, such as there was of it, was dead in our faces. However, I don’t think either Joyce or I found the time hang heavily on our hands. If one can’t be happy with the sun and the sea and the person one loves best in the world, it seems to me that one must be unreasonably difficult to please.

We fetched up off Southend Pier at just about eleven o’clock. A hoarse-voiced person in a blue jersey, who was leaning over the end, pointed us out some moorings that we were at liberty to pick up, and then watched us critically while I stowed away the sails and locked up everything in the boat which it was possible to steal. I had been to Southend before in the old days.

These simple precautions concluded, Joyce and I got in the dinghy and rowed to the steps. We were met by the gentleman in blue, who considerately offered to keep his eye on the boat for us while I “and the lady” enjoyed what he called “a run round the town.” I accepted his proposal, and having agreed with his statement that it was “a nice morning for a sail,” set off with Joyce along the mile of pier that separated us from the shore.

I don’t know that our adventures for the next two or three hours call for any detailed description. We wandered leisurely and cheerfully through the town, buying each other one or two trifles in the way of presents, and then adjourned for lunch to a large and rather dazzling hotel that dominated the sea front. It was a new effort on the part of Southend since my time, but, as Joyce said, it “looked the sort of place where one was likely to get asparagus.”

Its appearance did not belie it. At a corner table in the window, looking out over the sea, we disposed of what the waiter described as “two double portions” of that agreeable vegetable, together with an excellent steak and a bottle of sound if slightly too sweet burgundy. Then over a couple of cigarettes we discussed our immediate plans.

“I think I’d better catch the three-thirty back,” said Joyce. “I’ve got one or two things I want to do before I meet George, and in any case you mustn’t stay here too long or you’ll miss the tide.”

“That doesn’t really matter,” I said. “Only I suppose I ought to get back just in case Tommy has turned up. I can’t leave him sitting on a mud-flat all night.”

Joyce laughed. “He’d probably be a little peevish in the morning. Men are so unreasonable.”

I leaned across the table and took her hand. “When are you coming down again?” I asked. “Tomorrow?”

Joyce thought for a moment. “Tomorrow or the next day. It all depends if I see a chance of getting anything more out of George. I’ll write to you or send you a wire, dear, anyhow.”

I nodded. “All right,” I said; “and look here, Joyce; you may as well come straight to the hut next time. It’s not the least likely there’ll be any one there except me, and if there was you could easily pretend you wanted to ask the way to Tilbury. You see, if Gow wasn’t about, you would have to pull the dinghy all the way down the bank before you got on board the Betty, and that’s a nice, muddy, shin-scraping sort of job at the best of times.”

“Very well,” said Joyce. Then squeezing my hand a little tighter she added: “And my own Neil, you will be careful, won’t you? I always seem to be asking you that, but, oh my dear, if you knew how horribly frightened I am of anything happening to you. It will be worse than ever now, after last night. I don’t seem to feel it when I’m actually with you — I suppose I’m too happy — but when I’m away from you it’s just like some ghastly horrible sword hanging over our heads all the time. Neil darling, as soon as you get this money from McMurtrie — if you do get it — can’t we just give up the whole thing and go away and be happy together?”

I lifted her hand and pressed the inside of it against my lips.

“Joyce,” I said, “think what it means. It’s just funking life — just giving it up because the odds seem too heavy against us. I shouldn’t have minded killing Marks in the least. I should be rather proud of it. If I had, we would go away together tomorrow, and I should never worry my head as to what any one in the world was saying or thinking about me.” I paused. “But I didn’t kill him,” I added slowly, “and that just makes all the difference.”

Joyce’s blue eyes were very near tears, but they looked back steadily and bravely into mine.

“Yes, yes,” she said. “I didn’t really mean it, Neil. I was just weak for the moment — that’s all. Right down in my heart I want everything for you; I could never be contented with less. I want the whole world to know how they’ve wronged you; I want you to be famous and powerful and splendid, and I want the people who’ve abused you to come and smirk and grovel to you, and say that they knew all the time that you were innocent.” She stopped and took a deep breath. “And they shall, Neil. I’m as certain of it as if I saw it happening. I seem to know inside me that we’re on the very point of finding out the truth.”

I don’t think my worst enemy would accuse me of being superstitious, but there was a ring of conviction in Joyce’s voice which somehow or other affected me curiously.

“I believe you’re right,” I said. “I’ve got something of that sort of feeling too. Perhaps it’s infectious.” Then, letting go her hand, to spare the feelings of the waiter who had just come into the room, I sat back in my chair and ordered the bill.

We didn’t talk much on our way to the station. I think we were both feeling rather depressed at the prospect of doing without each other for at least twenty-four hours, and in any case the trams and motors and jostling crowd of holiday-makers who filled the main street would have rendered any connected conversation rather a difficult art.

A good many people favoured Joyce with glances of admiration, especially a spruce-looking young constable who officially held up the traffic to allow us to cross the road. He paid no attention at all to me, but I consoled myself with the reflection that he was missing an excellent chance of promotion.

At the station I put Joyce into a first-class carriage, kissed her affectionately under the disapproving eye of an old lady in the opposite corner, and then stood on the platform until the train steamed slowly out of the station.

I turned away at last, feeling quite unpleasantly alone. It’s no good worrying about what can’t be altered, however, so, lighting a cigar, I strolled back philosophically to the hotel, where I treated myself to the luxury of a hot bath before rejoining the boat.

It must have been pretty nearly half-past four by the time I reached the pier-head. My friend with the hoarse voice and the blue jersey was still hanging around, looking rather thirsty and exhausted after his strenuous day’s work of watching over the dinghy. I gave him half a crown for his trouble, and followed by his benediction pulled off for the Betty.

The wind had gone round a bit to the south, and as the tide was still coming in I decided to sail up to the creek in preference to using the engine. The confounded throb of the latter always got on my nerves, and apart from that I felt that the mere fact of having to handle the sails would keep my mind lightly but healthily occupied. Unless I was mistaken, a little light healthy occupation was exactly what my mind needed.

As occasionally happens on exceptionally fine days in late spring, the perfect clearness of the afternoon was gradually beginning to give place to a sort of fine haze. It was not thick enough, however, to bother me in any way, and under a jib and mainsail the Betty swished along at such a satisfactory pace that I was in sight of Gravesend Reach before either the light or the tide had time to fail me.

I thought I knew the entrance to the creek well enough by now to run her in under sail, though it was a job that required a certain amount of cautious handling. Anyhow I decided to risk it, and, heading for the shore, steered her up the narrow channel, which I had been careful to take the bearings of at low water.

I was so engrossed in this feat of navigation that I took no notice of anything else, until a voice from the bank abruptly attracted my attention. I looked up with a start, nearly running myself aground, and there on the bank I saw a gesticulating figure, which I immediately recognized as that of Tommy. I shouted a greeting back, and swinging the Betty round, brought up in almost the identical place where we had anchored on the previous night.

Tommy, who had hurried down to the edge of the water, gave me a second hail.

“Buck up, old son!” he called out. “There’s something doing.”

A suggestion of haste from Tommy argued a crisis of such urgency that I didn’t waste any time asking questions. I just threw over the anchor, and tumbling into the dinghy sculled ashore as quickly as I could.

“Sorry I kept you waiting, Tommy,” I said, as he jumped into the boat. “Been here long?”

“About three hours,” he returned. “I was beginning to wonder if you were dead.”

I shook my head. “I’m not fit to die yet,” I replied. “What’s the matter?”

He looked at his watch. “Well, the chief matter is the time. Do you think I can get to Sheppey by half-past nine?”

I paused in my rowing. “Sheppey!” I repeated. “Why damn it, Tommy, I’ve just come back from Sheppey.”

It was Tommy’s turn to look surprised. “The devil you have!” he exclaimed. “What took you there?”

“To be exact,” I said, “it was the Betty“; and then in as few words as possible I proceeded to acquaint him with the morning’s doings. I was just finishing as we came alongside.

“Well, that’s fine about the powder,” he said, scrambling on board. “Where’s Gow?”

“Joyce sent him off for a holiday,” I answered, “and he hasn’t come back yet.” Then hitching up the dinghy I added curiously: “What’s up, Tommy? Let’s have it.”

“It’s Latimer,” he said. “I told you I was expecting to hear from him. He sent me a message round early this morning, and I’ve promised him I’ll be in the creek under the German’s bungalow by half-past nine. I must get there somehow.”

“Oh, we’ll get there all right,” I returned cheerfully, “What’s the game?”

“I think he’s having a squint round,” said Tommy. “Anyhow I know he’s there on his own and depending on me to pick him up.”

“But what made him ask you?” I demanded.

“He knew I had a boat, and I fancy he’s working this particular racket without any official help. As far as I can make out, he wants to be quite certain what these fellows are up to before he strikes. You don’t get much sympathy in the Secret Service if you happen to make a mistake.”

“Well, it’s no good wasting time talking,” I said. “If we want to be there by half-past nine we must push off at once.”

“But what about you?” exclaimed Tommy. “You can’t come! He’s seen you, you know, at the hut.”

“What does it matter?” I objected. “If he didn’t recognize me as the chap who sent him the note at Parelli’s, we can easily fake up some explanation. Tell him I’m a new member of the Athenians, and that you happened to run across me and brought me down to help work the boat. There’s no reason one shouldn’t be a yachtsman and a photographer too.”

I spoke lightly, but as a matter of fact I was some way from trusting Tommy’s judgment implicitly with regard to Latimer’s straightforwardness about the restaurant incident, and also about his visit to the hut. All the same, I was quite determined to go to Sheppey. Things had come to a point now when there was nothing to be gained by over-caution. Either Latimer had recognized me or else he hadn’t. In the first event, he knew already that Tommy had been trying to deceive him, and that the mythical artist person was none other than myself. If that were so, I felt it was best to take the bull by the horns, and try to find out exactly what part he suspected me of playing. I had at least saved his life, and although we live in an ungrateful world, he seemed bound to be more or less prejudiced in my favour.

Apart from these considerations, Tommy would certainly want some help in working the Betty. He knew his job well enough, but with a haze on the river and the twilight drawing in rapidly, the mouth of the Thames is no place for single-handed sailing — especially when you’re in a hurry.

Tommy evidently recognized this, for he raised no further objections.

“Very well,” he said, with a rather reckless laugh. “We’re gambling a bit, but that’s the fault of the cards. Up with the anchor, Neil, and let’s get a move on her.”

I hauled in the chain, and then jumped up to attend to the sails, which I had just let down loosely on deck, in my hurry to put off in the dinghy. After a couple of unsuccessful efforts and two or three very successful oaths, Tommy persuaded the engine to start, and we throbbed off slowly down the creek—now quite a respectable estuary of tidal water.

I sat back in the well with a laugh. “I never expected a second trip tonight,” I said. “I’m beginning to feel rather like the captain of a penny steamer.”

Tommy, who was combining the important duties of steering and lighting a pipe, looked up from his labours.

“The Lyndon-Morrison Line!” he observed. “Tilbury to Sheppey twice daily. Passengers are requested not to speak to the man at the wheel.”

“I think, Tommy,” I said, “that we must make an exception in the case of Mr. Latimer.”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.