A Rogue By Compulsion (15)

By:

July 8, 2016

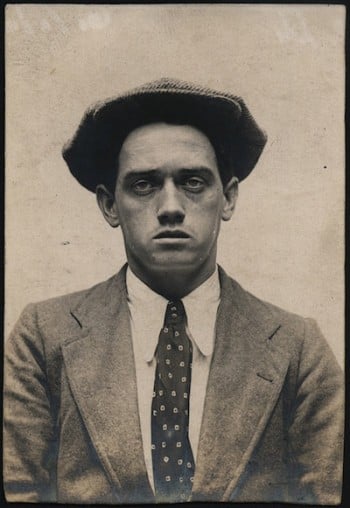

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

It’s not often that the weather in England is really appropriate to one’s mood, but the sunshine that was streaming down into Edith Terrace as I banged the front door at half-past eight the next morning seemed to fit in exactly with my state of mind. I felt as cheerful as a schoolboy out for a holiday. Apart altogether from the knowledge that I was going to spend a whole delightful day with Tommy and Joyce, the mere idea of getting on the water again was enough in itself to put me into the best of spirits.

I stopped for a moment at the flower-stall outside Victoria Station to buy Joyce a bunch of violets — she had always been fond of violets — and then calling up a taxi instructed the man to drive me to Fenchurch Street.

I found Tommy and Joyce waiting for me on the platform. The former looked superbly disreputable in a very old and rather dirty grey flannel suit, while Joyce, who was wearing a white serge skirt with a kind of green knitted coat, seemed beautifully in keeping with the sunshine outside.

“Hullo!” exclaimed Tommy. “We were just getting the jim-jams about you. Thought you’d eloped with Sonia or something.”

I shook my head. “I never elope before midday,” I said. “I haven’t the necessary stamina.”

I offered Joyce the bunch, which she took with a smile, giving my hand a little squeeze by way of gratitude. “You dear!” she said. “Fancy your remembering that.”

“Well, come along,” said Tommy. “This is the train all right; I’ve got the tickets and some papers.”

He opened the door of a first-class carriage just behind us, and we all three climbed in. “We shall have it to ourselves,” he added. “No one ever travels first on this line except the Port of London officials, and they don’t get up till the afternoon.”

We settled ourselves down, Tommy on one side and Joyce and I on the other, and a minute later the train steamed slowly out of the station. Joyce slipped her hand into mine, and we sat there looking out of the window over the sea of grey roofs and smoking chimney-stacks which make up the dreary landscape of East London.

“Have a paper?” asked Tommy, holding out the Daily Mail.

“No, thanks, Tommy,” I said. “I’m quite happy as I am. You can tell us the news if there is any.”

He opened the sheet and ran his eye down the centre page. “There’s nothing much in it,” he said, “bar this German business. No one seems to know what’s going to happen about that. I wonder what the Kaiser thinks he’s playing at. He can’t be such a fool as to want to fight half Europe.”

“How is the Navy these days?” I asked. “One doesn’t worry about trifles like that in Dartmoor.”

“Oh, we’re all right,” replied Tommy cheerfully. “The Germans haven’t got a torpedo to touch yours yet, and we’re still a long way ahead of ’em in ships. We could wipe them off the sea in a week if they came out to fight.”

“Well, that’s comforting,” I said. “I don’t want them sailing up the Thames till I’ve finished. I’ve no use for a stray shell in my line of business.”

“I tell you what I’m going to do, Neil,” said Tommy. “I was thinking it over in bed last night after you’d gone. If there is any possible sort of anchorage for a boat in this Cunnock Creek I shall leave the Betty there. It’s only a mile from your place, and then either Joyce or I can come down and see you without running the risk of being spotted by your charming pals. Besides, at a pinch it might be precious handy for you. If things got too hot on shore you could always slip away by water. It’s not as if you were dependent on the tides. Now I’ve had this little engine put in her she’ll paddle off any old time — provided you can get the blessed thing to start.”

“You’re a brick, Tommy,” I said gratefully. “There’s nothing I’d like better. But as for you and Joyce coming down —”

“Of course we shall come down,” interrupted Joyce. “I shall come just as soon as I can. Who do you think is going to look after you and do your cooking?”

“Good Lord, Joyce!” I said. “I’m in much too tight a corner to worry about luxuries.”

“That’s no reason why you should be uncomfortable,” said Joyce calmly. “I shan’t come near you in the day, while you’re working. I shall stay on the Betty and cook dinner for you in the evening, and then as soon as it’s dark you can shut up the place and slip across to the creek. Oh, it will be great fun — won’t it, Tommy?”

Tommy laughed. “I think so,” he said; “but I suppose there are people in the world who might hold a different opinion.” Then he turned to me. “It’s all right, Neil. We’ll give you two or three clear days to see how the land lies and shove along with your work. Joyce has got to find out where George is getting that cheque from, and I mean to look up Latimer and sound him about his dinner at Parelli’s. You’ll be quite glad to see either of us by that time.”

“Glad!” I echoed. “I shall be so delighted, I shall probably blow myself up. It’s you two I’m thinking of. The more I see of this job the more certain I am there’s something queer about it, and if there’s going to be any trouble down there I don’t want you and Joyce dragged into it.”

“We shan’t want much dragging,” returned Tommy. “As far as the firm’s business goes we’re all three in the same boat. We settled that last night.”

“So there’s nothing more to be said,” added Joyce complacently.

I looked from one to the other. Then I laughed and shrugged my shoulders. “No,” I said, “I suppose there isn’t.”

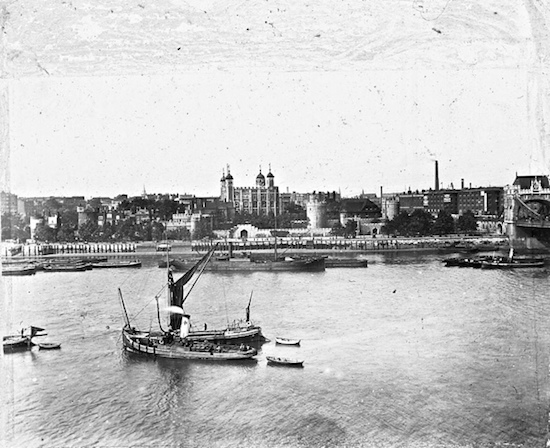

Through the interminable slums of Plaistow and East Ham we drew out in the squalid region of Barking Creek, and I looked down on the mud and the dirty brown water with a curious feeling of satisfaction. It was like meeting an old friend again after a long separation. The lower Thames, with its wharves, its warehouses, and its never-ceasing traffic, had always had a strange fascination for me; and in the old days, when I wanted to come to Town from Leigh or Port Victoria, I had frequently sailed my little six-tonner, the Penguin, right up as far as the Tower Bridge. I could remember now the utter amazement with which George had always regarded this proceeding.

“Are you feeling pretty strong this morning?” asked Tommy, breaking a long silence. “The Betty‘s lying out in the Ray, and the only way of getting at her will be to tramp across the mud. There’s no water for another four hours. We shall have to take turns carrying Joyce.”

“You won’t,” said Joyce. “I shall take off my shoes and stockings and tramp too. I suppose you’ve got some soap on board.”

“You’ll shock Leigh terribly if you do,” said Tommy. “It’s a beautiful respectable place nowadays — all villas and trams and picture palaces — rather like a bit of Upper Tooting.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said Joyce. “I’ve got very nice feet and ankles, and I’m sure it’s much less immoral than being carried in turns. Don’t you think so, Neil?”

“Certainly,” I said gravely. “No properly-brought-up girl would hesitate for a moment.”

We argued over the matter at some length: Tommy maintaining that he was the only one of the three who knew anything about the minds of really respectable people — a contention which Joyce and I indignantly disputed. As far as I can remember, we were still discussing the point when the train ran into Leigh station and pulled up at the platform.

“Here you are,” said Tommy, handing me a basket. “You freeze on to this; it’s our lunch. I want to get a couple more cans of paraffin before we go on board. There is some, but it’s just as well to be on the safe side.”

We left the station, and walking a few yards down the hill, pulled up at a large wooden building which bore the dignified title of “Marine and Yachting Stores.” Here Tommy invested in the paraffin and one or two other trifles he needed, and then turning off down some slippery stone steps, we came out on the beach. Before us stretched a long bare sweep of mud and sand, while out beyond lay the Ray Channel, with a number of small boats and fishing-smacks anchored along its narrow course.

“There’s the Betty,” said Tommy, pointing to a smart-looking little clinker-built craft away at the end of the line. “I’ve had her painted since you saw her last.”

“And from what I remember, Tommy,” I said, “she wanted it — badly.”

Joyce seated herself on a baulk of timber and began composedly to take off her shoes and stockings. “How deep does one sink in?” she asked. “I don’t want to get this skirt dirtier than I can help.”

“You’ll be all right if you hold it well up,” said Tommy, “unless we happen to strike a quicksand.”

“Well, you must go first,” said Joyce, “then if we do, Neil and I can step on you.”

Tommy chuckled, and sitting down on the bank imitated Joyce’s example, rolling his trousers up over the knee. I followed suit, and then, gathering up our various belongings, we started off gingerly across the mud.

Tommy led the way, his shoes slung over his shoulder, and a tin of paraffin in each hand. He evidently knew the lie of the land, for he picked out the firmest patches with remarkable dexterity, keeping on looking back to make sure that Joyce and I were following in his footsteps. It was nasty, sloppy walking at the best, however, for every step one took one went in with a squelch right up to the ankle, and I think we had all had pretty well enough by the time we reached the boat. Poor Joyce, indeed, was so exhausted that she had to sit down on the lunch basket, while Tommy and I, by means of wading out into the channel, managed to get hold of the dinghy.

Our first job on getting aboard was to wash off the mud. We sat in a row along the deck with our feet over the side; Tommy flatly refusing to allow us any farther until we were all properly cleaned. Then, while Joyce was drying herself and putting on her shoes and stockings, he and I went down into the cabin and routed out a bottle of whisky and a siphon of soda from somewhere under the floor.

“What we want,” he observed, “is a good stiff peg all round”; and the motion being carried unanimously as far as Joyce and I were concerned, three good stiff pegs were accordingly despatched.

“That’s better,” said Tommy with a sigh. “Now we’re on the safe side. There’s many a good yachtsman died of cold through neglecting these simple precautions.” Then jumping up and looking round he added cheerfully: “We shall be able to sail the whole way up; the wind’s dead east and likely to stay there.”

“I suppose you’ll take her out on the engine,” I said. “This is a nice useful ditch, but there doesn’t seem to be much water in it for fancy work.”

Tommy nodded. “You go and get in the anchor,” he said, “and I’ll see if I can persuade her to start. She’ll probably break my arm, but that’s a detail.”

He opened a locker at the back of the well, and squatted down in front of it, while I climbed along the deck to the bows and proceeded to hand in several fathoms of wet and slimy chain. I had scarcely concluded this unpleasant operation, when with a sudden loud hum the engine began working, and the next moment we were slowly throbbing our way forwards down the centre of the channel.

The Ray runs right down to Southend Pier, but there are several narrow openings out of it connecting with the river. Through one of these Tommy steered his course, bringing us into the main stream a few hundred yards down from where we had been lying. Then, turning her round, he handed the tiller over to Joyce, and clambered up alongside of me on to the roof of the cabin.

“Come on, Neil,” he said. “I’ve had enough of this penny steamer business. Let’s get out the sails and shove along like gentlemen.”

The Betty‘s rig was not a complicated one. It consisted of a mainsail, a jib, and a spinnaker, and in a very few minutes we had set all three of them and were bowling merrily upstream with the dinghy bobbing and dipping behind us. Tommy jumped down and switched off the engine, while Joyce, resigning the tiller to me, climbed up and seated herself on the boom of the mainsail. She had taken off her hat, and her hair gleamed in the sunshine like copper in the firelight.

I don’t think we did much talking for the first few miles: at least I know I didn’t. There is no feeling in the way of freedom quite so fine as scudding along in a small ship with a good breeze behind you; and after being cooped up for three years in a prison cell I drank in the sensation like a man who has been almost dying of thirst might gulp down his first draught of water. The mere tug of the tiller beneath my hand filled me with a kind of fierce delight, while the splash of the water as it rippled past the sides of the boat seemed to me the bravest and sweetest music I had ever heard.

I think Joyce and Tommy realized something of what I was feeling, for neither of them made any real attempt at conversation. Now and then the latter would jump up to haul in or let out the main sheet a little, and once or twice he pointed out some slight alteration which had been recently made in the buoying of the river. Joyce sat quite still for the most part, either smiling happily at me, or else watching the occasional ships and barges that we passed, most of which were just beginning to get under way.

We had rounded Canvey Island and left Hole Haven some little distance behind us, when Tommy, who was leaning over the side staring out ahead, suddenly turned back to me.

“There’s someone coming round the point in a deuce of a hurry,” he remarked. “Steam launch from the look of it. Better give ’em a wide berth, or we’ll have their wash aboard.”

I bent down and took a quick glance under the spinnaker boom. A couple of hundred yards ahead a long, white, vicious-looking craft was racing swiftly towards us, throwing up a wave on either side of her bows that spread out fanwise across the river.

I shoved down the helm, and swung the Betty a little off her course so as to give them plenty of room to go by. They came on without slackening speed in the least, and passed us at a pace which I estimated roughly to be about sixteen knots an hour. I caught a momentary glimpse of a square-shouldered man with a close-trimmed auburn beard crouching in the stern, and then the next moment a wave broke right against our bows, drenching all three of us in a cloud of flying spray.

Tommy swore vigorously. “That’s the kind of river-hog who ought to be choked,” he said. “If I —”

He was interrupted by a sudden exclamation from Joyce. She had jumped up laughing when the spray swept over her, and now, holding on to the rigging, she was pointing excitedly to something just ahead of us.

“Quick, Tommy!” she said. “There’s a man in the water — drowning. They’ve swamped his boat.”

In a flash Tommy had leaped to the side. “Keep her going,” he shouted to me. “We’re heading straight for him.” Then scrambing aft he grabbed hold of the tow rope and swiftly hauled the dinghy alongside.

“I’ll pick him up, Tommy,” I said quietly. “You look after the boat: you know her better than I do.”

He nodded, and calling to Joyce to take over the tiller sprang up on to the deck ready to lower the sails. I cast off the painter, all but one turn, and handing the end to Joyce, told her to let it go as soon as I shouted. Then, pulling the dinghy right up against the side of the boat, I waited my chance and dropped down into her.

I was just getting out the sculls, when a sudden shout from Tommy of “There he is!” made me look hurriedly round. About twenty yards away a man was splashing feebly in the water, making vain efforts to reach an oar that was floating close beside him.

“Let her go, Joyce!” I yelled, and the next moment I was tugging furiously across the intervening space with the loose tow rope trailing behind me.

I was only just in time. Almost exactly as I reached the man he suddenly gave up struggling, and with a faint gurgling sort of cry disappeared beneath the water. I leaned out of the boat, and plunging my arm in up to the shoulder, clutched him by the collar.

“No, you don’t, Bertie,” I said cheerfully. “Not this journey.”

It’s a ticklish business dragging a half-drowned man into a dinghy without upsetting it, but by getting him down aft, I at last managed to hoist him up over the gunwale. He came in like some great wet fish, and I flopped him down in the stern sheets. Then with a deep breath I sat down myself. I was feeling a bit pumped.

For a moment or two my “catch” lay where he was, blowing, gasping, grunting, and spitting out mouthfuls of dirty water. He was a little weazened man of middle age, with a short grizzled beard. Except for a pair of fairly new sea-boots, he was dressed in old nondescript clothes which could not have taken much harm even from the Thames mud. Indeed, on the whole, I should think their recent immersion had done them good.

“Well,” I said encouragingly, “how do you feel?”

With a big effort he raised himself on his elbow. “Right enough, guv’nor,” he gasped, “right enough.” Then, sinking back again, he added feebly: “If you see them oars o’ mine, you might pick ’em up.”

There was a practical touch about this that rather appealed to me. I sat up, and, looking round, discovered the Betty about forty yards away. Tommy had got the sails down and set the engine going, and he was already turning her round to come back and pick us up. I waved my hand to him — a greeting which he returned with a triumphant hail.

Standing up, I inspected the surrounding water for any sign of my guest’s belongings. I immediately discovered both oars, which were drifting upstream quite close to one another and only a few yards away; but except for them there was no sign of wreckage. His boat and everything else in it had vanished as completely as a submarine.

I salvaged the oars, however, and had just got them safely on board, when the Betty came throbbing up, and circled neatly round us. Tommy, who was steering, promptly shut down the engine to its slowest pace, and reaching up I grabbed hold of Joyce’s hand, which she held out to me, and pulled the dinghy alongside.

“Very nice, Tommy,” I said. “Lipton couldn’t have done it better.”

“How’s the poor man?” asked Joyce, looking down pityingly at my prostrate passenger.

At the sound of her voice the latter roused himself from his recumbent position, and made a shaky effort to sit up straight.

“He’ll be all right when he’s got a little whisky inside him,” I said. “Come on, Tommy; you catch hold, and I’ll pass him over.”

I stooped down, and, taking him round the waist, lifted him right up over the gunwale of the Betty, where Tommy received him rather like a man accepting a sack of coals. Then, catching hold of the tow rope, I jumped up myself, and made the dinghy fast to a convenient cleat.

Tommy dumped down his burden on one of the well seats.

“You’ve had a precious narrow squeak, my friend,” he observed pleasantly.

The man nodded. “If you hadn’t ‘a come along as you did, sir, I’d ‘ave bin dead by now — dead as a dog-fish.” Then turning round he shook his gnarled fist over the Betty‘s stern in the direction of the vanished launch. “Sunk me wi’ their blarsted wash,” he quavered; “that’s what they done.”

“Well, accidents will happen,” I said; “but they were certainly going much too fast.”

“Accidents!” he repeated bitterly; “this warn’t no accident. They done it a purpose — the dirty Dutchmen.”

“Sunk you deliberately!” exclaimed Tommy. “What on earth makes you think that?”

A kind of half-cunning, half-cautious look came into our visitor’s face.

“Mebbe I knows too much to please ’em,” he muttered, shaking his head. “Mebbe they’d be glad to see old Luke Gow under the water.”

I thought for a moment that the shock of the accident had made him silly, but before I could speak Joyce came out of the cabin carrying half a tumbler of neat whisky.

“You get that down your neck,” said Tommy, “and you’ll feel like a two-year-old.”

I don’t know if whisky is really the correct antidote for Thames water, but at all events our guest accepted the glass and shifted its contents without a quiver. As soon as he had finished Tommy took him by the arm and helped him to his feet.

“Now come along into the cabin,” he said, “and I’ll see if I can fix you up with some dry kit.” Then turning to me he added: “You might get the sails up again while we’re dressing, Neil; it’s a pity to waste any of this breeze.”

I nodded, and resigning the tiller to Joyce, climbed up on to the deck, and proceeded to reset both the mainsail and the spinnaker, which were lying in splendid confusion along the top of the cabin. I had just concluded this operation when Tommy and our visitor reappeared — the latter looking rather comic in a grey jersey, a pair of white flannel trousers, and an old dark blue cricketing blazer and cap.

“I’ve been telling our friend Mr. Gow that he’s got to sue these chaps,” said Tommy. “He knows who they are: they’re a couple of Germans who’ve got a bungalow on Sheppey, close to that little creek we used to put in at.”

“You make ’em pay,” continued Tommy. “They haven’t a leg to stand on, rushing past like that. They as near as possible swamped us.”

Mr. Gow cast a critical eye round the Betty. “Ay! and you’d take a deal o’ swampin,’ mister. She’s a fine manly little ship, an’ that’s a fact.” Then he paused. “It’s hard on a man to lose his boat,” he added quietly; “specially when ‘is livin’ depends on ‘er.”

“What do you do?” I asked. “What’s your job?”

Mr. Gow hesitated for a moment. “Well, in a manner o’ speakin’, I haven’t got what you might call no reg’lar perfession, sir. I just picks up what I can outer the river like. I rows folks out to their boats round Tilbury way, and at times I does a bit of eel fishing — or maybe in summer there’s a job lookin’ arter the yachts at Leigh and Southend. It all comes the same to me, sir.”

“Do you know Cunnock Creek?” asked Tommy.

“Cunnock Crick!” repeated Mr. Gow. “Why, I should think I did, sir. My cottage don’t lie more than a mile from Cunnock Crick. Is that where you’re makin’ for?”

Tommy nodded. “We were thinking of putting in there,” he said. “Is there enough water?”

“Plenty o’ water, sir — leastways there will be by the time we get up. It runs a bit dry at low tide, but there’s always a matter o’ three to four feet in the middle o’ the channel.”

This was excellent news, for the Betty with her centre-board up only drew about three feet six, so except at the very lowest point the creek would always be navigable.

“Is it a safe place to leave a boat for the night with no one on board?” inquired Tommy.

Mr. Gow shook his head. “I wouldn’t go as far as that, sir. None o’ the reg’lar boatmen or fishermen wouldn’t touch ‘er, but they’re a thievin’ lot o’ rascals, some o’ them Tilbury folk. If they happened to come across ‘er, as like as not they’d strip ‘er gear, to say nothin’ of the fittings.” Then he paused. “But if you was thinkin’ o’ layin’ ‘er up there for the night, I’d see no one got monkeyin’ around with ‘er. I’d sleep aboard meself.”

“Well, that’s a bright notion,” said Tommy, turning to me. “What do you think, Neil?”

“I think it’s quite sound,” I answered. “Besides, he can help me look after her for the next two or three days. I shall be too busy to get over to the creek much myself.” Then putting my hand in my pocket I pulled out Joyce’s envelope, and carefully extracted one of the five-pound notes from inside. “Look here, Mr. Gow!” I added, “we’ll strike a bargain. If you’ll stay with the Betty for a day or so, I’ll give you this fiver to buy or hire another boat with until you can get your compensation out of our German friends. I shall be living close by, but I shan’t have time to keep my eye on her properly.”

Mr. Gow accepted the proposal and the note with alacrity. “I’m sure I’m very much obliged to you, sir,” he said gratefully. “I’ll just run up to my cottage when we land to get some dry clothes, and then I’ll come straight back and take ‘er over. She won’t come to no harm, not with Luke Gow on board; you can reckon on that, sir.”

He touched his cap, and climbing up out of the well, made his way forward, as though to signalize the fact that he was adopting the profession of our paid hand.

“I’m so glad,” said Joyce quietly. “I shan’t feel half so nervous now I know you’ll have someone with you.”

Tommy nodded. “It’s a good egg,” he observed. “I think old whiskers is by way of being rather grateful.” Then he paused. “But what swine those German beggars must be not to have stopped! They must have seen what had happened.”

“I wonder what he meant by hinting that they’d done it purposely,” I said.

Tommy laughed. “I don’t know. I asked him in the cabin, but he wouldn’t say any more. I think he was only talking through his hat.”

“I’m not so sure,” I said doubtfully. “He seemed to have some idea at the back of his mind. I shall sound him about it later on.”

With the wind holding good and a strong tide running, the Betty scudded along at such a satisfactory pace that by half-past twelve we were already within sight of Gravesend Reach. There is no more desolate-looking bit of the river than the stretch which immediately precedes that crowded fairway. It is bounded on each side by a low sea wall, behind which a dreary expanse of marsh and salting spreads away into the far distance. Here and there the level monotony is broken by a solitary hut or a disused fishing hulk, but except for the passing traffic and the cloud of gulls perpetually wheeling and screaming overhead there is little sign of life or movement.

“You see them two or three stakes stickin’ up in the water?” remarked Mr. Gow suddenly, pointing away towards the right-hand bank.

I nodded.

“Well, you keep ’em in line with that little clump o’ trees be’ind, an’ you’ll just fetch the crick nicely.”

He and Tommy went forward to take in the spinnaker, while, following the marks he had indicated, I brought the Betty round towards her destination. Approaching the shore I saw that the entrance to the creek was a narrow channel between two mud-flats, both of which were presumably covered at high tide. I called to Joyce to wind up the centre-board to its fullest extent, and then, steering very carefully, edged my way in along this drain, while Mr. Gow leaned over to leeward diligently heaving the lead.

“Plenty o’ water,” he kept on calling out encouragingly. “Keep ‘er goin’, sir, keep ‘er goin’. Inside that beacon, now up with ‘er a bit. That’s good!”

He discarded the lead and hurried to the anchor. I swung her round head to wind, Tommy let down the mainsail, and the next moment we brought up with a grace and neatness that would almost have satisfied a Solent skipper.

We were in the very centre of a little muddy creek with high banks on either side of it. There was no other boat within sight; indeed, although we were within three miles of Tilbury, anything more desolate than our surroundings it would be difficult to imagine.

Mr. Gow assisted us to furl the sails and put things straight generally, and then coming aft addressed himself to me.

“I don’t know what time you gen’lemen might be thinkin’ o’ leavin’; but if you could put me ashore now I could be back inside of the hour.”

“Right you are,” I said. “I’ll do that straight away.”

We both got into the dinghy, and in a few strokes I pulled him to the bank, where he stepped out on to the mud. Then he straightened himself and touched his cap.

“I haven’t never thanked you properly yet, sir, for what you done,” he observed. “You saved my life, and Luke Gow ain’t the sort o’ man to forget a thing like that.”

I backed the boat off into the stream. “Well, if you’ll save our property from the Tilbury gentlemen,” I said, “we’ll call it quits.”

When I got back to the ship I found Tommy and Joyce making preparations for lunch.

“We thought you’d like something before you pushed off,” said Tommy. “One can scout better on a full tummy.”

“You needn’t apologize for feeding me,” I replied cheerfully. “I’ve a lot of lost time to make up in the eating line.”

It was a merry meal, that little banquet of ours in the Betty‘s cabin. The morning’s sail had given us a first-rate appetite, and in spite of the somewhat unsettled state of our affairs we were all three in the best of spirits. Indeed, I think the unknown dangers that surrounded us acted as a sort of stimulant to our sense of pleasure. When you are sitting over a powder mine it is best to enjoy every pleasant moment as keenly as possible. You never know when you may get another.

At last I decided that it was time for me to start.

“I tell you what I think I’ll do, Tommy,” I said. “I’ll see if there’s any way along outside the sea-wall. I could get right up to the place then without being spotted, if there should happen to be any one there.”

Tommy nodded. “That’s the idea,” he said. “And look here: I brought this along for you. I don’t suppose you’ll want it, but it’s a useful sort of thing to have on the premises.”

He pulled out a small pocket revolver, loaded in each chamber, and handed it over to me.

I accepted it rather doubtfully. “Thanks, Tommy,” I said, “but I expect I should do a lot more damage with my fists.”

“Oh, please take it, Neil,” said Joyce simply.

“Very well,” I answered, and stuffing it into my side pocket, I buttoned up my coat. “Now, Tommy,” I said; “if you’ll put me ashore we’ll start work.”

It was about a hundred yards to the mouth of the creek, and with the tide running hard against us it was quite a stiff little pull. Tommy, however, insisted on taking me the whole way down, just to see whether there was any chance of getting along outside the sea-wall. We landed at the extreme point, and jumping out on to the mud, I picked my way carefully round the corner and stared up the long desolate stretch of river frontage. The tide was still some way out, and although the going was not exactly suited to patent-leather boots, it was evidently quite possible for any one who was not too particular.

I turned round and signalled to Tommy that I was all right; then, keeping in as close as I could to the sea-wall, I set off on my journey. It was slow walking, for every now and then I had to climb up the slope to get out of the way of some hopelessly soft patch of mud. On one of these occasions, when I had covered about three-quarters of a mile, I peered cautiously over the top of the bank. Some little way ahead of me, right out in the middle of the marsh, I saw what I imagined to be my goal. It was a tiny brick building with a large wooden shed alongside, the latter appearing considerably the newer and more sound of the two.

I was inspecting it with the natural interest that one takes in one’s future country house, when quite suddenly I saw the door of the building opening. A moment later a man stepped out on to the grass, and looked quickly round as though to make certain that there was no one watching. Although the distance was about three hundred yards I recognized him at once.

It was my friend of the restaurant — Mr. Bruce Latimer.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.