Stuffed (13)

By:

June 24, 2016

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of the forthcoming Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (British Library Publishing, October 2016). STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

In last month’s STUFFED, I wrote about the weird history of salsa. But as I was looking into how Mexico’s many salsas birthed what Americans think of as salsa, I realized that the weirder history was really that of mole — a pre-Columbian sauce that took a more obscure path than salsa. Today the general view of mole is “that weird Mexican sauce with chocolate in it,” but that misconception turns out to be the result of centuries of chicanery, both directed and general, on the part of Spanish and French imperialists in Mexico.

While salsa was becoming more of a condiment — because fancy European chefs and Spanish colonizers were trying to marginalize it, and also because the Mexican people’s move towards democracy was dragging their food with them (condiment variety is a well known side effect/cause of democratization) — mole was undergoing more subtle changes.

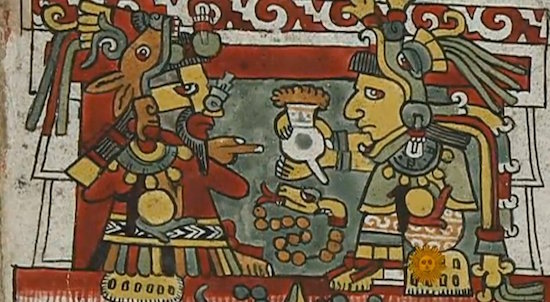

Mole is, at its simplest, a sauce made of ground-up chiles and liquid. Aztecs had been eating it for centuries, often mixed with herbs, tomato, avocado (guacamole), or ground-up seeds (typically from a pumpkin or other squash) as a thickener. With the arrival of Cortés and the Spanish in the early 1500s, mole started to be made using some European techniques and ingredients — thickened with flour (instead of just chile powder, seeds, or tomato) and flavored with spices like clove, cumin, and cinnamon. They also started to use chocolate — previously, at least in Aztec lands, an ingredient reserved for the aristocracy — in recipes.

Many moles were transformed into mestizo dishes, a merging of the native and foreign — thus mole poblano, a thick, complicated mixture of indigenous and imported ingredients, was adopted as a sort of national dish. Whether mole poblano was also an attempt to colonize mole (it even has a 16th-century nonsense genesis story, about chocolate falling into a mole being prepared for a bishop) is another story.

On both sides, there were objectors to the mestizo-ization of mole. Spanish people in Mexico, who viewed themselves as foreigners abroad, i.e., not as Mexican, were unlikely to adopt mole of any sort. They continued to eat French- and Spanish-style food. Meanwhile, many indigenous people continued to eat, generally, the food they’d eaten before Cortés.

For these reasons, and a complicated stew of other causes that include class identity, weak palates, and the popularity of French food with Spanish aristocrats (who brought droves of French chefs to Mexico in the 19th century: e.g. Alejandro Pardo, the French-trained, Madrid-born chef and prolific cookbook author), mole was never brought back to Spain in the same way that, for example, “curry” was brought back to Britain. The Spanish did invent the colorful, if emasculated, sweet pepper powder later mastered in Hungary and called paprika — which strongly suggests that their biggest quibble with mole was its hot spiciness.

The weirder story of mole and Europe involves not Spain, but France — a culture deeply attuned, as the semiotician Roland Barthes demonstrated in the 1950s, via his analyses of, for example, the French mythology of red wine (seen as a social equalizer and the drink of the proletariat), to the political subtext of food. Since at least as long ago as the Jacquerie uprising in 1358, the French aristocracy had associated the color red with lower -class revolt and violence. Fear of the color red is common enough to have a name — erythrophobia — sufferers of which typically avoid red foods. It seems fair to describe the French aristocracy as erythrophobic.

The association of revolution and red food was cross-pollinated during the French Revolution, when the bonnet rouge worn by revolutionaries gave way to the red flag of the Jacobites. The flag was waved by red tomato-eating savages from Marseille and other points south; the tomato had not caught on in Paris yet, but was a hit in the Mediterranean.

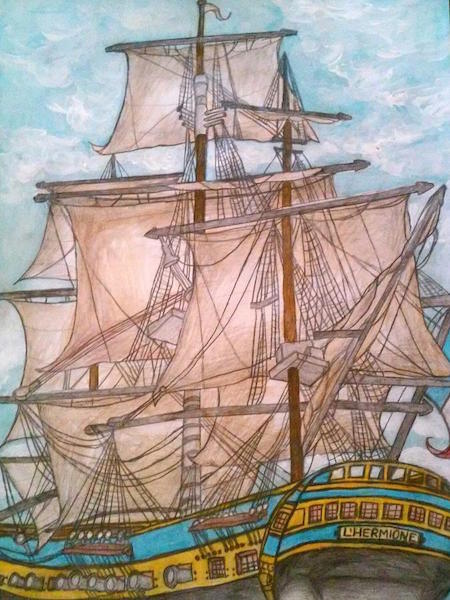

As the Reign of Terror settled into France, this fear of red was overshadowed by more immediate horrors. However, when the monarchy was restored, in the 1830s, King Louis-Philippe send an armada of ships — including the French flagship Hermione — to Mexico, under the pretext of debt collection redress for damage to a pastry shop 10 (!) years earlier, but in actuality to revenge the aristocracy upon the source of France’s tomatoes. Tomatoes were then making alarming inroads in French (provincial) cuisine. The popular La Cuisinière de la Campagne (in print throughout the 19th century) now included tomato recipes that, even for the relatively enlightened reign of Louis-Phillipe, could best be described as symbolo-politically disastrous.

During the Pastry War (also known as the First Franco-Mexican War, 1838–1839), the French made a great deal of trouble. They blew some things up — including the newly returned to duty Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna, who lost a leg in the bombardment of Veracruz. Meanwhile, Louis-Philippe’s scouts carried out their true mission: investigating the red threat. What they found no doubt troubled them. Red, reddish, and reddish-brown moles were everywhere. Though they may have come across the Atlantic to stamp out the tomato menace, what French secret agents discovered was a country awash in red chile mole.

However, before the French could even begin to deal with the red menace’s unexpected escalation, it became clear to the English and Spanish (who had been dragged into the conflict by France as leverage) that the invasion’s purported aim was a front. Under back-room diplomatic pressure, France hastily agreed to settle the Pastry War dispute for 600,000 pesos and some vague assurances that tomato and chile exports would be limited. For a time, this seems to have worked. The Second Republic, which overthrew King Louis-Philippe and officially adopted the slogan “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité,” halted the anti-rouge campaign from 1848–1852. But during the erythrophobic Second Empire, France once again “intervened” in Mexico — the so-called Maximilian Affair, a story for another time.

Thanks to these militarized semiotic interventions, then, although the tomato continued to creep into French cuisine, the French palate remained remarkably resistant to the chile pepper.

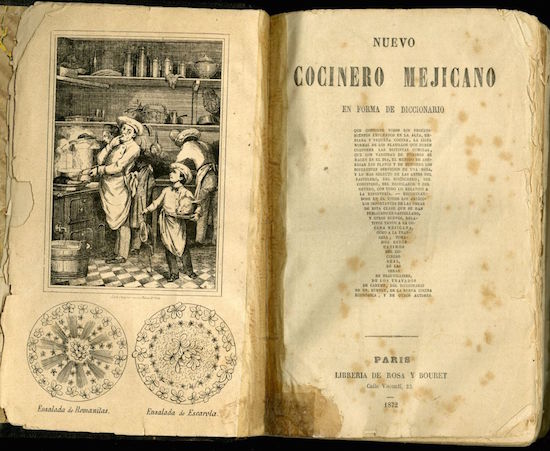

The Paris publishing company of Rosa y Bouret had been publishing Spanish-language books for decades, but it was during the late 19th century that they moved into Mexican cookbooks. Among these, their flagship product was the Nuevo Cocinero Mexicano en Forma de Diccionario, which they published in a variety of editions for distribution in Paris and Mexico until 1903. Today, it is clear that the Nuevo Cocinero was part of France’s ongoing cultural cold war against the subversive potential of Mexican mole.

The Nuevo Cocinero, as discussed last time, foisted French sauces on Mexico, marginalized salsas and moles, and even campaigned against the (red) tamale, attempting to brand it as peasant food. Alongside Rosa y Bouret’s cookbooks we find a flurry of French travel logs disparaging Mexican cuisine.

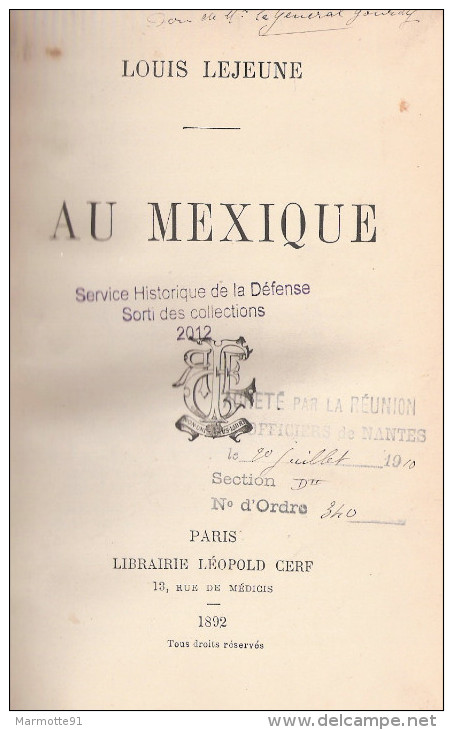

“We got to know Mexican Food and it was not a brilliant debut… it was difficult to discern the ingredients in the stew… and the inevitable beans” (a frequently reprinted account from the 1880s). “There are innumerable miserable indigenous people who have nothing to eat but chile peppers and tortillas” (La Mexique, 1857). “Les Mexicains ne sont pas gourmands” (Au Mexique, 1892). The author of this last travelog went on to complain that he was served turkey fricassee with chile peppers, and eggs also flavored with chiles — imagine the nerve!

A number of accounts in the popular Revue des Deux Mondes (Paris, 1846–1850s) suggested that Mexican food was only tolerable when it was French food cooked in Mexico. Gustave Aimard let slip the core of these fears when, in La Loi de Lynch (1859), an adventure story set in Mexico, he described a character like so: “Elle est difficile, elle préfère la cuisine mexicaine à la nôtre” (She is difficult, she prefers Mexican food to ours). In the rare instances that the chile pepper appeared in French cookbooks, it was called piment enragé (mad pepper) and only called for in recipes of Provençal, Andalusian, Portuguese or Italian origin. A mid-century medical text (Dictionnaire de médecine usuelle, 1849) was typical in warning that the extreme heat from eating a piment enragé could last for many days!

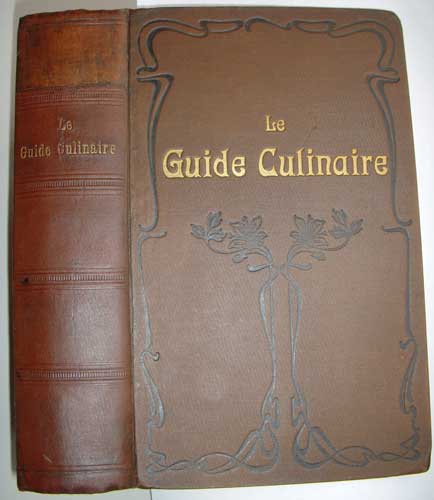

Alas, the French elites’ 19th-century cultural cold war against mole was mostly successful. In Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire (1903), which provides the building blocks of all French sauces, the “mother sauces” are described. Escoffier generally stays with the sauces Carême described in 1833, but adds a French version of an Italian tomato sauce (the tomato-loving insurrectionaries from Marseille had finally won!) — but no mole. In fact, there are four recipes in Le Guide Culinaire which Escoffier calls “à la Mexicaine,” when in fact they merely constitute a garnish with grilled chiles, mushrooms and diced tomato. Which is pretty remarkable, really — it would be like calling something “French Style” because you put a sprig of parsley, half a hard-boiled egg, and a pat of butter next to it.

In very recent years, Mexican food has finally reached Paris — and, I gather, you can actually get a nice mole on the Left Bank these days (though probably still not on the Right). But if you squint, you can still pick up bits of tomato fear floating around the European and American zeitgeist. Attack of the Killer Tomatoes is a silly example. The cultivation of “cherry” and “grape” tomatoes is a more serious example. (Who invented the cherry tomato? Our friends at the terrific Gastropod podcast did a recent piece tracking down the culprits.) Can you imagine the tomato terror that would cause a civilization to do something so depraved as shrinking the tomato? Do you have any idea how many centuries it took for indigenous Mexicans to get it as big as it is now?

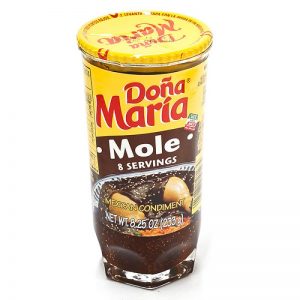

Today, the only mass-marketed mole — Herdez Doña María, now owned by Hormel — is a venerable (launched in 1968), semi-reasonable concoction containing chocolate and peanuts. It advertises itself, believe it or not, as a “Mexican Condiment.”

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.