A Rogue By Compulsion (11)

By:

June 14, 2016

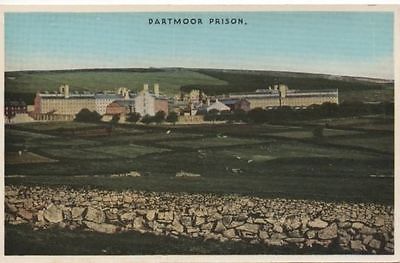

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

It was the unexpectedness of the thing that threw me off my guard. With a savage effort I recovered myself almost at once, but it was too late to be of any use. At the sound of my voice all the colour had left Joyce’s face. Her hands went up to her breast, and with a low cry she stepped forward and then stood there white and swaying, gazing at me with wide-open, half-incredulous eyes.

“My God!” she whispered; “it’s you — Neil!”

I think she would have fallen, but I came to her side, and putting my arm round her shoulders gently forced her into one of the chairs. Then I knelt in front of her and took her hands in mine. I saw it was no good trying to deceive her.

“I didn’t know,” I said simply; “I followed George here.”

“What have they done to you?” she moaned. “What have they done to you, my Neil? And your hands — oh, your poor dear hands!”

She burst out crying, and bending down pressed her face against my fingers.

“Don’t, Joyce,” I said, a little roughly. “For God’s sake don’t do that.”

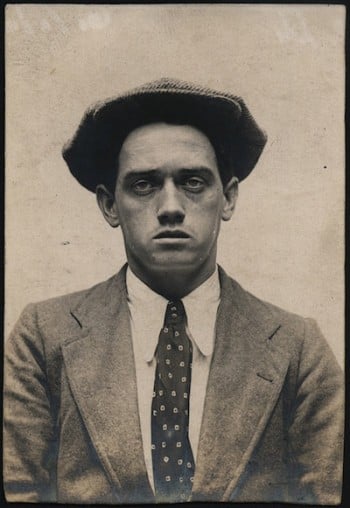

Half unconsciously I pulled away my hands, which three years in Dartmoor had certainly done nothing to improve.

My abrupt action seemed to bring Joyce to herself. She left off sobbing, and with a sudden hurried glance round the room jumped up from her chair.

“I must speak to Jack — now at once,” she whispered. “He mustn’t let any one else into the flat.”

She stopped for a moment to dry her eyes, which were still wet with tears, and then walking quickly to the door disappeared into the passage. She was only gone for a few seconds. I just had time to get to my feet when she came back into the room, and shutting the door behind her, turned the key in the lock. Then with a little gasp she leaned against the wall. For the first time I realized what an amazingly beautiful girl she had grown into.

“Neil, Neil,” she said, stretching out her hands; “is it really you!”

I came across, and taking her in my arms very gently kissed her forehead.

“My little Joyce,” I said. “My dear, brave little Joyce.”

She buried her face in my coat, and I felt her hand moving up and down my sleeve.

“Oh,” she sobbed, “if I had only known where to find you before! Ever since you escaped I have been hoping and longing that you would come to me.” Then she half pushed me back, and gazed up into my face with her blue, tear-stained eyes. “Where have you been? What have they done to you? Oh, tell me — tell me, Neil. It’s breaking my heart to see you so different.”

For a moment I hesitated. I would have given much if I could have undone the work of the last few minutes, for even to be revenged on George I would not willingly have brought my wretched troubles and dangers into Joyce’s life. Now that I had done so, however, there seemed to be no other course except to tell her the truth. It was impossible to leave her in her present agony of bewilderment and doubt.

Pulling up one of the chairs I sat down, drawing her on to my knee.

“If I had known it was you, Joyce,” I said, “I should have let George go to the devil before I followed him here.”

“But why?” she asked. “Where should you go to if you didn’t come to me?”

“Oh, my poor Joyce,” I said bitterly; “haven’t I brought enough troubles and horrors into your life already?”

She interrupted me with a low, passionate cry. “You talk like that! You, who have lost everything for my wretched sake! Can’t you understand that every day and night since you went to prison I’ve loathed and hated myself for ever telling you anything about it? If I’d dreamed what was going to happen I’d have let Marks —”

I stopped her by crushing her in my arms, and for a little while she remained there sobbing bitterly, her cheek resting on my shoulder. For a moment or two I didn’t feel exactly like talking myself.

Indeed it was Joyce who spoke first. Raising her head she wiped away her tears, and then sitting up gazed long and searchingly into my face.

“There is nothing of you left,” she said, “nothing except your eyes — your dear, splendid eyes. I think I should have known you by those even if you hadn’t spoken.” Then, taking my hands again and pressing them to her, she added passionately: “Oh, tell me what it means, Neil. Tell me everything that’s happened to you from the moment you got away.”

“Very well,” I said recklessly: “I shall be dragging you into all sorts of dangers, and I shall be breaking my oath to McMurtrie, but after all that’s just the sort of thing one would expect from an escaped convict.”

Step by step, from the moment when I had jumped over the wall into the plantation, I told her the whole astounding story. She listened to me in silence, her face alone betraying the feverish interest with which she was following every word. When I came to the part about Sonia kissing me (I told her everything just as it had happened) her hands tightened a little on mine, but except for that one movement she remained absolutely still.

It was not until I had finished speaking that she made her first comment. After I stopped she sat on for a moment just as she was; and then quite suddenly her face lighted up, and with a little low laugh that was half a sob she leaned forward and slid her arm round my neck.

“Tommy was right,” she whispered. “He said you’d do something wonderful. I knew it too, but oh, Neil dear, I’ve suffered tortures wondering where you were and what had happened.”

Then, sitting up again and pushing back her hair, she began to ask me questions.

“These people — Dr. McMurtrie and the others — do you believe their story?”

“No,” I said bluntly. “I am quite certain they were lying to me.”

“Why should they have helped you, then?”

“I haven’t the remotest idea,” I admitted. “I am only quite sure that neither McMurtrie nor Savaroff are what they pretend to be. Besides, you remember the hints that Sonia gave me.”

“Ah, Sonia!” Joyce looked down and played with one of the buttons of my coat. “Is she — is she very pretty?” she asked.

“She seems likely to be very useful,” I said. Then, stroking Joyce’s soft curly hair, which had become all tousled against my shoulder, I added: “But I’m answering questions when all the time I’m dying to ask them. There are a hundred things you’ve got to tell me. What are you doing here? Why do you call yourself Miss Vivien? Are you really living next door to Tommy? And George — how on earth do you come to be mixed up with George?”

“I’ll tell you everything,” she said, “only I must know all about you first. Why were you following George? You don’t mean to let him know who you are? Oh, Neil, Neil, promise me that you won’t do that.”

“Joyce,” I said slowly, “I want to find out who killed Seton Marks. I don’t suppose there is the least chance of my doing so, and if I can’t I most certainly mean to wring George’s neck. That was chiefly what I broke out of prison for.”

“Yes, yes,” she said feverishly, “but there is a chance. You’ll understand when I’ve explained.” She put her hands to her forehead. “Oh, I hardly know where to begin.”

“Begin anywhere,” I said. “Tell me why you’re pretending to be a palmist.”

She got up from my knee and, walking slowly to the table, seated herself on the end.

“I wanted money,” she said; “and I wanted to meet one or two people who might be useful about you.”

“But I left eight hundred pounds for you with Tommy,” I exclaimed. “You got that?”

She nodded. “It’s in the bank now. I have been keeping it in case anything happened. You don’t suppose I was going to spend it? How could I have helped you then even when I got the chance?”

“But, my dear Joyce,” I protested, “the money was for you. And you couldn’t have helped me with it in any case. I had plenty more waiting for me when my sentence was out.”

“When your sentence was out,” repeated Joyce fiercely. “Do you think I was going to let you stop in prison till then!” She checked herself with an effort. “I had better tell you everything from the beginning,” she said. “I couldn’t write any more to you, because I was only allowed to send the two letters, and I knew both of them would be read by somebody.”

She paused a moment.

“I went away after the trial. I was very ill, and Tommy took me to a little place called Looe, down in Cornwall. We stayed there nearly six months. When I came back I took the flat next to him and called myself Miss Vivien. I had made up my mind then what I was going to do. You see there were only two possible ways in which I could help you. One was to find out who killed Marks, and the other was to get you out of prison — anyhow. Of course, after the trial, it seemed madness to think about the first, but then I just had three things to go on. I knew that you were innocent, I knew that for some reason of his own George had lied about you, and I knew that there had been some one else in the flat the day of the murder.”

“The man who was with Marks when you arrived,” I said. “But you saw him go away, and there was nothing to connect him with the murder, except the fact that he didn’t turn up at the trial. Sexton himself had to admit that in his speech.”

“There was his face,” said Joyce quietly. “It was a dreadful face. It looked as if all the goodness had been burned out of it.”

“There are about five hundred gentlemen like that in Princetown,” I said, “including several of the warders. Did they ever find out anything about him?”

Joyce shook her head. “Mr. Sexton did everything he could, but it was quite useless. Whoever he was, the man never came forward, and you see there was no one except me who even knew what he was like. It was partly that which first gave me the idea of becoming a palmist. I thought that up here in the West End I was more likely to come across him than anywhere else. And then there were other people I meant to meet — men in the Government who might be able to get your sentence shortened. I knew I was beautiful, and with some men you can do anything if you’re beautiful, and—and you don’t care.”

“Joyce!” I cried, “for God’s sake don’t tell me —”

“No,” she broke in passionately: “there’s nothing to tell you. But if the chance had come I’d have sold myself a thousand times over to get you out of prison. The only man I’ve met who could do anything has been Lord Lammersfield, and he….” She paused, then with a little break in her voice she added: “Well, I think Lord Lammersfield is rather like Tommy in some ways.”

“I suppose there are still one or two white men about,” I said.

“Lord Lammersfield used to be at the Home Office once, so of course his influence would count for a great deal. Well, he did all that was possible for me, but about six months ago he told me that there was no chance of your being let out for another three years. It was then that I made up my mind to get to know George.”

I thrust my hand in my pocket and pulled out my cigarette case. “You — you’ve got rather thorough ideas about friendship, Joyce,” I said, a little unsteadily. “Can I smoke?”

She picked up a box of matches from the table, and coming across seated herself on the arm of my chair.

“Have I?” she said simply. “Well, you taught me them.”

She struck a match and held it to my cigarette.

“How did you manage it?” I asked.

“Oh, it was easy enough. I asked Lord Lammersfield to bring him here one day. You know what George is like; he would never refuse to do anything a Cabinet Minister suggested. Of course he had no idea who I was until he arrived.”

“It must have been quite a pleasant surprise for him,” I said grimly.

“Did he recognize you at once?”

Joyce shook her head. “He had only seen me at the trial, and I had my hair down then. Besides, two years make a lot of difference.”

“They’ve made a lot of difference in you,” I said. “They’ve turned you from a pretty child into a beautiful woman.”

With a little low, contented laugh Joyce again laid her head on my shoulder. “I think,” she said, “that that’s the only one of George’s opinions I’d like you to share.”

There was a moment’s silence. Then I gently twisted one of her loose curls round my finger.

“My poor Joyce,” I said, “you seem to have been wading in some remarkably unpleasant waters for my sake.”

She shivered slightly. “Oh, it was hateful in a way, but I didn’t care. I knew George was hiding something that might help to get you out of prison, and what did my feelings matter compared with that! Besides —” she smiled mockingly — “for all his cleverness and his wickedness George is a fool — just the usual vain fool that most men are about women. It’s been easy enough to manage him.”

“He knows who you are now, of course?” I said.

She nodded. “I told him. He would have been almost certain to find out, and then he would probably have been suspicious. As it is he thinks our meeting was just pure chance.”

“But surely,” I objected, “he must have guessed you were on my side?”

She gave a short, bitter laugh. “Yes,” she said, “he guessed that all right. It’s what he calls ‘a sacred bond between us.’ There are times, you know, when George is almost funny.”

“There are times,” I said, “when he must make Judas Iscariot feel sick.”

“I sometimes wonder why I haven’t killed him,” she went on slowly. “I think I should have if he had ever tried to kiss me. As it is —” she laughed again in the same way — “as it is we are becoming great friends. He is taking me out to dinner at the Savoy tonight.”

“But if he doesn’t try to make love to you —” I began.

“Oh!” she said, with a little shrug of her shoulders, “that’s coming. At present he imagines that he is being clever and diplomatic. Also there’s a business side to the matter.”

“Yes,” I said; “there would be with George.”

“He’s horribly frightened of you. Of course he tries to hide it from me, but I can see that ever since you escaped from prison he has been living in a state of absolute terror. His one idea at present is a frantic hope that you will be recaptured. That’s partly where I come in.”

“You?” I repeated.

“Yes. He thinks that sooner or later, when you want help, you will probably write and tell me where you are.”

“And then you are to pass the good news on to him?”

She nodded. “He says that if I let him know at once, he will arrange to get you safely out of the country.”

I lay back in the chair and laughed out loud.

Joyce, who was still sitting on the arm, looked down happily into my face. “Oh,” she said, “I love to hear you laugh again.” Then, slipping her hand into mine, she went on: “I suppose he means to arrange it so that it will look as if you had been caught by accident while he was trying to help you.”

“I expect so,” I said. “I should be out of the way again then, and you would be so overcome by gratitude — Oh, yes, there’s quite a Georgian touch about it.”

The sharp tinkle of an electric bell broke in on our conversation. Joyce jumped up from the chair, and for a moment both remained listening while “Jack” answered the door.

“I know who it is,” whispered Joyce. “It’s old Lady Mortimer. She had an appointment for one o’clock.”

“But what have you arranged to do?” I asked. “There’s no reason you should put all your people off. I can go away for the time, or stop in another room, or something.”

“No, no; it’s all right,” whispered Joyce. “I’ll tell you in a minute.”

She waited until we heard the front door shut, and then coming back to me sat down again on my knee.

“I told Jack,” she said, “not to let any one into the flat till three o’clock. I have an appointment then I ought to keep, but that still gives us nearly two hours. I will send Jack across to Stewart’s to fetch us some lunch, and we’ll have it in here. What would you like, my Neil?”

“Anything but eggs and bacon,” I said, getting out another cigarette.

She jumped up with a laugh, and, after striking me a match, went out into the passage, leaving the door open. I heard her call the page-boy and give him some instructions, and then she came back into the room, her eyes dancing with happiness and excitement.

“Isn’t this splendid!” she exclaimed. “Only this morning I was utterly miserable wondering if you were dead, and here we are having lunch together just like the old days in Chelsea.”

“Except for your hair, Joyce,” I said. “Don’t you remember how it was always getting in your eyes?”

“Oh, that!” she cried; “that’s easily altered.”

She put up her hands, and hastily pulled out two or three hairpins. Then she shook her head, and in a moment a bronze mane was rippling down over her shoulders exactly as it used to in the old days.

“I wish I could do something like that,” I said ruefully. “I’m afraid my changes are more permanent.”

Joyce came up and thrust her arm into mine. “My poor dear,” she said, pressing it to her. “Never mind; you look splendid as you are.”

“Won’t your boy think there’s something odd in our lunching together like this?” I asked. “He seems a pretty acute sort of youth.”

“Jack?” she said. “Oh, Jack’s all right. He was a model in Chelsea. I took him away from his uncle, who used to beat him with a poker. He doesn’t know anything about you, but if he did he would die for you cheerfully. He’s by way of being rather grateful to me.”

“You always inspired devotion, Joyce,” I said, smiling. “Do you remember how Tommy and I used to squabble as to which of us should eventually adopt you?”

She nodded, almost gravely; then with a sudden change back to her former manner, she made a step towards the inner room, pulling me after her.

“Come along,” she said. “We’ll lunch in there. It’s more cheerful than this, and anyway I want to see you in the daylight.”

I followed her in through the curtains, and found myself in a small, narrow room with a window which looked out on the back of Burlington Arcade. A couple of chairs, a black oak gate-legged table, and a little green sofa made up the furniture.

Joyce took me to the window, and still holding my arm, made a second and even longer inspection of McMurtrie’s handiwork.

“It’s wonderful, Neil,” she said at last. “You look fifteen years older and absolutely different. No one could possibly recognize you except by the way you speak.”

“I’ve been practising that,” I said, altering my voice. “I shouldn’t have given myself away if you hadn’t taken me by surprise.”

She smiled again happily. “It’s so good to feel that you’re safe, even if it’s only for a few days.” Then, letting go my arm, she crossed to the sofa. “Come and sit down,” she went on. “We’ve got to decide all sorts of things, and we shan’t have too much time.”

“I’ve told you my plans, Joyce,” I said, “such as they are. I mean to go through with this business of McMurtrie’s, though I’m sure there’s something crooked at the bottom of it. As for the rest —” I shrugged my shoulders and sat down on the sofa beside her; “well, I’ve got the sort of hand one has to play alone.”

Joyce looked at me quietly and steadily.

“Neil,” she said; “do you remember that you once called me the most pig-headed infant in Chelsea?”

“Did I?” I said. “That was rather rude.”

“It was rather right,” she answered calmly; “and I haven’t changed, Neil. If you think Tommy and I are going to let you play this hand alone, as you call it, you are utterly and absolutely wrong.”

“Do you know what the penalties are for helping an escaped convict?” I asked.

She laughed contemptuously. “Listen, Neil. For three years Tommy and I have had no other idea except to get you out of prison. Is it likely we should leave you now?”

“But what can you do, Joyce?” I objected. “You’ll only be running yourselves into danger, and —”

“Oh, Neil dear,” she interrupted; “it’s no good arguing about it. We mean to help you, and you’ll have to let us.”

“But suppose I refuse?” I said.

“Then as soon as Tommy comes back tomorrow I shall tell him everything that you’ve told me. I know your address at Pimlico, and I know just about where your hut will be down the Thames. If you think Tommy will rest for a minute till he’s found you, you must have forgotten a lot about him in the last three years.”

She spoke with a kind of indignant energy, and there was an obstinate look in her blue eyes, which showed me plainly that it would be waste of time trying to reason with her.

I reflected quickly. Perhaps after all it would be best for me to see Tommy myself. He at least would appreciate the danger of dragging Joyce into the business, and between us we might be able to persuade her that I was right.

“Well, what are your ideas, Joyce?” I said. “Except for keeping my eye on George I had no particular plan until I heard from McMurtrie.”

Joyce laid her hand on my sleeve. “Tomorrow,” she said, “you must go and see Tommy. He is coming back by the midday train, and he will get to the flat about two o’clock. Tell him everything that you have told me. I shan’t be able to get away from here till the evening, but I shall be free then, and we three will talk the whole thing over. I shan’t make any more appointments here after tomorrow.”

“Very well,” I said reluctantly. “I will go and look up Tommy, but I can’t see that it will do any good. I am only making you and him liable to eighteen months’ hard labour.” She was going to speak, but I went on. “Don’t you see, Joyce dear, there are only two possible courses open to me? I can either wait and carry out my agreement with McMurtrie, or I can go down to Chelsea and force the truth about Marks’s death out of George — if he really knows it. Dragging you two into my wretched affairs won’t alter them at all.”

“Yes, it will,” she said obstinately. “There are lots of ways in which we can help you. Suppose these people turn out wrong, for instance; they might even mean to give you up to the police as soon as they’ve got your secret. And then there’s George. If he does know anything about the murder I’m the only person who is the least likely to find it out. Why —”

A discreet knock at the outer door interrupted her, and she got up from the sofa.

“That’s Jack with the lunch,” she said. “Come along, Neil dear. We won’t argue about it any more now. Let’s forget everything for an hour, — just be happy together as if we were back in Chelsea.”

She held out her hands to me, her lips smiling, her blue eyes just on the verge of tears. I drew her towards me and gently stroked her hair, as I used to do in the old days in Chelsea when she had come to me with some of her childish troubles. I felt an utter brute to think that I could ever have doubted her loyalty, even for an instant.

How long we kept the luckless Jack waiting on the mat I can’t say, but at last Joyce detached herself, and crossing the room, opened the door. Jack came in carrying a basket in one hand and a table-cloth in the other. If he felt any surprise at finding Joyce with her hair down he certainly didn’t betray it.

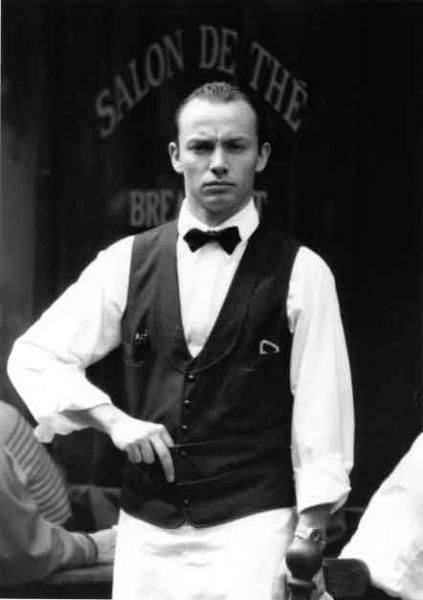

“I got what I could, Mademoiselle,” he observed, putting down his burdens. “Oyster patties, galatine, cheese-cakes, and a bottle of champagne. I hope that will please Mademoiselle?”

“It sounds distinctly pleasing, Jack,” said Joyce gravely. “But then you always do just what I want.”

The boy flushed with pleasure, and began to lay the table without even so much as bestowing a glance on me. It was easy enough to see that he adored his young mistress—adored her far beyond questioning any of her actions.

All through lunch — and an excellent lunch it was too — Joyce and I were ridiculously happy. Somehow or other we seemed to drop straight back into our former jolly relations, and for the time I almost forgot that they had ever been interrupted. In spite of all she had been through since, Joyce, at the bottom of her heart, was just the same as she had been in the old days — impulsive, joyous, and utterly unaffected. All her bitterness and sadness seemed to slip away with her grown-up manner; and catching her infectious happiness, I too laughed and joked and talked as cheerfully and unconcernedly as though we were in truth back in Chelsea with no hideous shadow hanging over our lives. I even found myself telling her stories about the prison, and making fun of one of the chaplain’s sermons on the beauties of justice. At the time I remembered it had filled me with nothing but a morose fury.

It was the little clock on the mantlepiece striking a quarter to three which brought us back to the realities of the present.

“I must go, Joyce,” I said reluctantly, “or I shall be running into some of your Duchesses.”

She nodded. “And I’ve got to do my hair by three, and turn myself back from Joyce into Mademoiselle Vivien — if I can. Oh, Neil, Neil; it’s a funny, mad world, isn’t it!” She lifted up my hand and moved it softly backwards and forwards against her lips. Then, suddenly jumping up, she went into the next room, and came back with my hat and stick.

“Here are your dear things,” she said; “and I shall see you tomorrow evening at Tommy’s. I shan’t leave him a note — somebody might open it; I shall just let you go and find him yourself. Oh, I should love to be there when he realizes who it is.”

“I know just what he’ll do,” I said. “He’ll stare at me for a minute; then he’ll say quite quietly, ‘Well, I’m damned,’ and go and pour himself out a whisky.”

She laughed gaily. “Yes, yes,” she said. “That’s exactly what will happen.” Then with a little change in her voice she added: “And you will be careful, won’t you, Neil? I know you’re quite safe; no one can possibly recognize you; but I’m frightened all the same — horribly frightened. Isn’t it silly of me?”

I kissed her tenderly. “My Joyce,” I said, “I think you have got the bravest heart in the whole world.”

And with this true if rather inadequate remark I left her.

I had plenty to think about during my walk back to Victoria. Exactly what result the sharing of my secret with Tommy and Joyce would have, it was difficult to forecast, but it opened up a disquieting field of possibilities. Rather than get either of them into trouble I would cheerfully have thrown myself in front of the next motor bus, but if such an extreme course could be avoided I certainly had no wish to end my life in that or any other abrupt fashion until I had had the satisfaction of a few minutes’ quiet conversation with George.

I blamed myself to a certain extent for having given way to Joyce. Still, I knew her well enough to be sure that if I had persisted in my refusal she would have stuck to her intention of trying to help me against my will. That would only have made matters more dangerous for all of us, so on the whole it was perhaps best that I should go and see Tommy. I had not the faintest doubt he would be anxious enough to help me himself if I would let him, but he would at least see the necessity for keeping Joyce out of the affair. We ought to be able to manage her between us, though when I remembered the obstinate look in her eyes I realized that it wouldn’t be exactly a simple matter.

I stopped at a book-shop just outside Victoria, which I had noticed on the previous evening. I wanted to order a copy of a book dealing with a certain branch of high explosives that I had forgotten to ask McMurtrie for, and when I had done that I took the opportunity of buying a couple of novels by Wells which had been published since I went to prison. Wells was a luxury which the prison library didn’t run to.

With these tucked under my arm, and still pondering over the unexpected results of my chase after George, I continued my walk to Edith Terrace. As I reached the house and thrust my key into the lock the door suddenly opened from the inside, and I found myself confronted by the apparently rather embarrassed figure of Miss Gertie ‘Uggins.

“I ‘eard you a-comin’,” she observed, rubbing one hand down her leg, “so I opened the door like.”

“That was very charming of you, Gertrude,” I said gravely.

She tittered, and then began to retreat slowly backwards down the passage. “There’s a letter for you in the sittin’-room. Come by the post after you’d gorn. Yer want some tea?”

“I don’t mind a cup,” I said. “I’ve been eating and drinking all day; it seems a pity to give it up now.”

“I’ll mike yer one,” she remarked, nodding her head. “Mrs. Oldbury’s gorn out shoppin’.”

She disappeared down the kitchen stairs, and opening the door of my room I discovered the letter she had referred to stuck up on the mantelpiece. I took it down with some curiosity. It was addressed to James Nicholson, Esq., and stamped with the Strand postmark. I did not recognize the writing, but common-sense told me that it could only be from McMurtrie or one of his crowd.

When I opened the envelope I found that it contained a half-sheet of note-paper, with the following words written in a sloping, foreign-looking hand:

“You will receive either a message or a visitor at five o’clock tomorrow afternoon. Kindly make it convenient to be at home at that hour.”

That was all. There was no signature and no address, and it struck me that as an example of polite letter-writing it certainly left something to be desired. Still, the message was clear enough, which was the chief point, so, folding it up, I thrust it back into the envelope and put it away in my pocket. After all, one can’t expect a really graceful literary style from a High Explosives Syndicate.

I wondered whether the note meant that the preparations which were being made for me at Tilbury were finally completed. McMurtrie had promised me a week in Town, and so far I had only had two days; still I was hardly in a position to kick if he asked me to go down earlier. Anyhow I should know the next day, so there seemed no use in worrying myself about it unnecessarily.

It was my intention to spend a quiet interval reading one of my books, before going out somewhere to get some dinner. In pursuance of this plan I exchanged my boots for a pair of slippers and settled myself down comfortably in the only easy-chair in the room. In about ten minutes’ time, faithful to her word, Gertie ‘Uggins brought me up an excellent cup of tea, and stimulated by this and the combined intelligence and amorousness of Mr. Wells’s hero, I succeeded in passing two or three very agreeable hours.

At seven o’clock I roused myself rather reluctantly, put on my boots again, and indulged in the luxury of a wash and a clean collar. Then, after ringing the bell and informing Mrs. Oldbury that I should be out to dinner, I left the house with the pleasantly vague intention of wandering up West until I found some really attractive restaurant.

It was a beautiful evening, more like June than the end of April; and with a cigarette alight, I strolled slowly along Victoria Street, my mind busy over the various problems with which Providence had seen fit to surround me. I had got nearly as far as the Stores, when a sudden impulse took me to cross over and walk past our offices. A taxi was coming up the road, so I waited for a moment on the pavement until it had passed. The back part of the vehicle was open, and as it came opposite to me, the light from one of the big electric standards fell clear on the face of the man inside. He was sitting bolt upright, looking straight out ahead, but in spite of his opera hat and his evening dress I recognized him at once. It was the man with the scar — the man I had imagined to be tracking me on the previous evening.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.